This report is based on research conducted by Abt Associates in partnership with the MacColl Center for Health Care Innovation and Bailit Health Purchasing, Cambridge, MA under contract to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), Rockville, MD (Contract Nos. 290-2010-00004-I/ 290-32009-T). The findings and conclusions in this document are those of the authors, who are responsible for its contents; the findings and conclusions do not necessarily represent the views of AHRQ. Therefore, no statement in this report should be construed as an official position of AHRQ or of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

None of the investigators have any affiliations or financial involvement that conflicts with the material presented in this report.

The information in this report is intended to help health care decisionmakers—patients and clinicians, health system leaders, and policymakers, among others—make well-informed decisions and thereby improve the quality of health care services. This report is not intended to be a substitute for the application of clinical judgment. Anyone who makes decisions concerning the provision of clinical care should consider this report in the same way as any medical reference and in conjunction with all other pertinent information, i.e., in the context of available resources and circumstances presented by individual patients.

This report is made available to the public under the terms of a licensing agreement between the author and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. This report may be used and reprinted without permission except those copyrighted materials that are clearly noted in the report. Further reproduction of those copyrighted materials is prohibited without the express permission of copyright holders.

Persons using assistive technology may not be able to fully access information in this report. For assistance contact EffectiveHealthCare@ahrq.hhs.gov.

Suggested citation: Coleman K, Wagner E, Schaefer J, Reid R, LeRoy L. Redefining Primary Care for the 21st Century. White Paper. (Prepared by Abt Associates, in partnership with the MacColl Center for Health Care Innovation and Bailit Health Purchasing, Cambridge, MA under Contract No.290-2010-00004-I/ 290-32009-T.) AHRQ Publication No. 16(17)-0022-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; October 2016.

Investigator Affiliations

Katie Coleman, Edward Wagner, and Judith Schaefer, MacColl Center for Health Care Innovation; Robert Reid, University of Toronto; and Lisa LeRoy, Abt Associates.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge our colleagues at AHRQ and on the technical expert workgroup for partnering with us in conceptualizing high-quality, comprehensive care.

Contents

Introduction

What is Primary Care?

What Do We Know Now About High-Performing Primary Care?

What is the Role of Patients and Families in Primary Care?

What Does High-Quality, Comprehensive Primary Care Look Like in the 21st Century?

Comprehensiveness

High-Quality

Team-Based Care

Measuring Comprehensive, High-Quality Primary Care

Conclusions

References

Tables

Table 1. Congruence between major frameworks of high-performing primary care

Table 2. Domains of the triple, quadruple, or quintuple aim and illustrative measure examples

Figures

Figure 1. Creating high-quality comprehensive primary care

Figure 2. Southcentral Foundation Team redesign before and after

Figure 3. The primary care team

Figure 4. Blueprint for provision of patient-centered team-based care

Introduction

The Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research (AHRQ) funded Abt Associates and its partners, the MacColl Center for Healthcare Innovation and Bailit Health Purchasing, to conduct research on how to configure and pay for the workforce that is needed to deliver fully comprehensive, high-quality primary care across the U.S. population. A first step was to clarify and articulate the definition of high-quality, comprehensive primary care at a time when primary care is undergoing great change in the United States. The changes in primary care structure and processes themselves affect definitions of high-quality and comprehensive services. However, in order to consider workforce and team configurations that are needed, not to provide just a basic level of primary care but an optimal level of primary care, we wanted to be explicit about what we mean by comprehensive and high-quality. The paper sets out definitions for the field to discuss in the context of developing optimal primary care team configurations.

What is Primary Care?

In the nearly 50 years since the first mention of "primary care" in the academic literature, the role of generalists has evolved and changed along with the U.S. health care landscape. In the 1950s, when the U.S. spent 5 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP) on health care, primary care providers accounted for more than half of U.S. doctors and functioned as both real-life and television heroes.1 Forty years later, the rise of third party payment and an increasing emphasis on sub-specialty care meant that primary care made up less than a third of providers.2 Today, evidence of primary care's effectiveness continues to mount,3 and—due in part to the historic Affordable Care Act—primary care is becoming recognized as the backbone of a rational U.S. health system.4 Through these changes, the defining features of primary care have remained consistent. From the Alma-Ata Declaration that primary care is the key to achieving health for all5 to Barbara Starfield's seminal work describing primary care "provided to populations undifferentiated by gender, disease, or organ system,"6 to the latest Institute of Medicine's report7 a consensus is emerging that primary care is:

- First contact, accessible.

- Continuous.

- Coordinated.

- Comprehensive.

- Whole person/accountable.

Primary Care: "the provision of integrated, accessible health care services by clinicians who are accountable for addressing a large majority of personal health care needs, developing a sustained partnership with patients, and practicing in the context of family and community." – Institute of Medicine 19967

Recent efforts to expand this definition recognize that primary care is also patient-focused and quality oriented—characteristics shared by other specialties as well.8

What Do We Know Now About High-Performing Primary Care?

Though evidence from a variety of sources indicates that not all generalist practices are meeting the definition of primary care described above, demographic, practice, and policy changes are re-emphasizing the importance of fully developed primary care.8 For example, with the aging of the U.S. population and the growing prevalence and complexity of chronic illness,9 evidence has shown that redesigned primary care—where prepared practice teams partner with informed, activated patients—is necessary for good disease management.10 Recent initiatives from large employers, health plans, policymakers, and academics to define and spread the Patient-Centered Medical Home have increased our understanding of primary care's ability to improve patient health and reduce inappropriate utilization of health services,11,12 an important contribution as health care costs rise to nearly a fifth of our gross domestic product.13 Although multiple groups have projected a shortage of primary care physicians,14-16 team-based primary care is recognized as an effective and efficient solution to expanding the availability of primary care.17 Clearly, primary care is central to health reform, both for patients and for health systems wagering that accountable, coordinated, first-contact care can reduce health care costs.

What, then, are the features of great primary care practices that consistently deliver high-quality care for patients? Several recent studies have examined the components or building blocks of effective primary care practices. These components are not evidenced by plaques or checked boxes, but are made manifest in the way the practice operates and delivers care in partnership with patients. Based on the literature and input from two technical expert panels, the Safety Net Medical Home Initiative (SNMHI) hypothesized eight key change concepts that effective primary care practices must implement. They are (1) Engaged Leadership; (2) Quality Improvement Strategy; (3) Empanelment; (4) Continuous & Team-based Healing Relationships; (5) Organized, Evidence-Based Care; (6) Patient-Centered Interactions; (7) Enhanced Access; and (8) Care Coordination.18 The experience of SNMHI practices suggested that these key changes are best implemented in sequence, with four foundational elements preceding implementation of elements five through eight. With technical assistance, practices serving low income individuals and socially complex patients were able to improve their capabilities across these domains.19

In a subsequent effort, the Center for Excellence in Primary Care at the University of California San Francisco visited practices with high rates of patient and staff satisfaction, improving clinical health outcomes, and stable finances to understand the shared features of great primary care. From those visits they discerned 10 shared building blocks of high-performing primary care: engaged leadership; data-driven improvement, empanelment, team-based care, patient-team partnership, population management, continuity of care, prompt access to care, comprehensiveness and care coordination, template of the future.20 Among the Change Concepts, the Building Blocks framework, and other models (including the well-recognized Patient-Centered Medical Home standards from the National Committee on Quality Assurance21 and the recent report titled "America's Most Valuable Care: Primary Care" from the Peterson Center on Healthcare and Stanford's Clinical Excellent Research Center)22 the similarities are striking, with an emphasis on continuous improvement in the quality of care, using a team to deliver all the services patients need, and providing ready access to the patient panel for all their needs.

Table 1. Congruence between major frameworks of high-performing primary care

| 10 Building Blocks | Safety Net Medical Home Initiative | NCQA PCMH 2014 | America’s Most Valuable Care | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bodenheimer et al.20 | Wagner et al.,18 | National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA), 21 | Peterson Center on Health Care & Stanford Medicine Clinical Excellence Research Center,22 | |

| Engaged leadership | * | * | ||

| Data-driven improvement | * | * | * | |

| Empanelment | * | * | 0 | |

| Team-based care | * | * | * | * |

| Patient-team partnership | * | * | 0 | * |

| Population management | * | * | * | * |

| Continuity of care | * | * | * | |

| Prompt access to care | * | * | * | * |

| Comprehensiveness & care coordination | * | * | 0 | * |

| Template of the future# | * | 0 | * |

* = element fully present in the framework; 0 = element partially present in the framework; blank = element not present in the framework

# = From Bodenheimer: "a daily schedule that does not rely on the 15-minute in-person clinician visit but offers patients a variety of e-visits, telephone encounters, group appointments, and visits with other team members. Clinicians would have fewer and longer in-person visits and protected time for e-visits and telephone visits. With a team empowered to share the care, clinicians would be able to assume a new role—clinical leader and mentor of the team." (page 169)

What is the Role of Patients and Families in Primary Care?

Productive interactions between informed, activated patients and prepared, proactive care teams are at the heart of good health care.23 Indeed, the Institute of Medicine recognizes patient centeredness as a core component of quality care.24 In order to partner fully with patients and families to co-create health, hospitals, clinics, and health care workers are renewing their emphasis on patient- and family- centeredness. This emphasis includes a recognition and respect for patients' values, preferences, and expressed needs; coordination and integration of care; information, communication, and education; physical comfort; emotional support and alleviation of fear and anxiety; involvement of family and friends; transition and continuity; and good access to care.25

Primary care practices implementing the Patient-Centered Medical Home acknowledge the core role of the patient in improving their own health. That means grappling with language and cultural discordance between patients and providers as well as literacy and numeracy challenges that may adversely impact communication and information sharing. It also means finding ways to incorporate shared decisionmaking and self-management support as a regular part of care, and eliciting and responding to patients' preferences and values for how, when, and where they want to receive care.

Practices are also increasingly involving patients in quality improvement efforts, asking for their guidance through focus groups, surveys, quality improvement committees, or advisory boards to change processes or even to co-design buildings.26,27 Recently, the newly formed Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute funded several interventions designed for and with patients. For example, in Learning to Integrate Neighborhoods and Clinical Care (LINCC), Group Health patients co-designed a community resource specialist role for primary care.28 Patients designed the community health liaison job description and activities, served on a community oversight board to link neighborhood resources, and acted as co-investigators in designing the evaluation. This level of patient engagement—in multiple ways and times throughout an initiative—is a promising strategy for increasing patient-centeredness in both clinical care and research, and a recognition that actively including patients and families in health care quality can improve care.

What Does High-Quality, Comprehensive Primary Care Look like in the 21st Century?

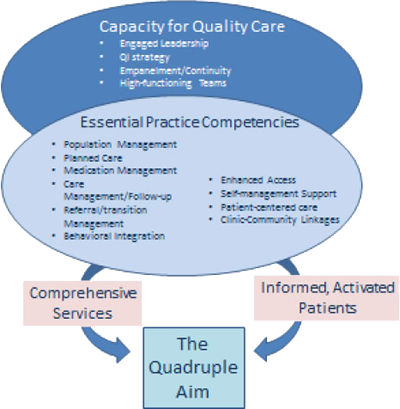

Keeping a panel of patients healthy requires that productive interactions between patients and their families and care teams occur across a wide-ranging, holistic set of needs. In our view, a high-quality primary care practice must meet the consensus definition of primary care—especially comprehensiveness—and have both the capacity and competencies in place that ensure the provision of services that optimize their patients' health and health care experiences, while limiting costs to patients and society, the triple aim. Figure 1 depicts our conceptualization of high-quality, comprehensive primary care. Its foundation is a well-led, continuously improving practice organization that partners with patients by linking each to a specific provider and a high-functioning team. These components form the foundation of both the Building Blocks and Change Concepts described above. Together, they provide the capacity to deliver high-quality, patient- and family-centered primary care.

Recent qualitative studies of high-performing primary care practices suggest that these practices produce benchmark levels of performance by engaging their well-organized, multi-disciplinary practice teams in the performance of several key activities or functions that in aggregate routinely deliver evidence-based services tailored to patients' needs and preferences.17

Functions such as the regular review of patient data looking for care gaps (panel management) and the regular review and improvement of medication regimens (medication management) increase the likelihood that patients receive evidence-based care. Self-management support and attention to health literacy and numeracy, as well as other functions such as behavioral health integration and care management, enhance the practice's ability to meet a broader array of patient needs. Finally, comprehensive high-quality primary care practices accept responsibility for coordinating referrals and transitions to and from more expensive health care resources such as specialists and hospitals as well as to important community resources, as needed by patients.

Figure 1. Creating high-quality comprehensive primary care

A good provider cannot offer all the functions that define high-quality primary care alone—it takes a team.29,30 In fact, many of these competencies described above are done as well or better by other members of the care team at potentially lower cost.31 And, in an era of expanded health care coverage, team-based care offers a means to expand primary care capacity without a complementary increase in primary care physicians.32

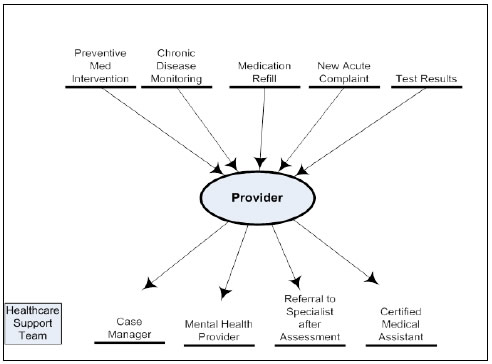

See Figure 2 below for an example of how Malcolm Baldrige Award winner Southcentral Foundation in Alaska redesigned their primary care team to expand capacity and better meet patient needs. 5

Figure 2. Southcentral Foundation Team redesign before and after

Before

After

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality is supporting an effort to make operational these lessons about high-performing, comprehensive, team-based care, to reach beyond early adopters and enable practices across the Nation to re-envision how they provide care. The purpose of this work is to explore more deeply team structures that contribute to high-quality comprehensive primary care. The effort will culminate in the proposal of exemplary care team models for a variety of contexts (urban vs. rural, integrated vs. unaffiliated, varying patient social and medical care needs). But first, we must begin with definitions—of high-quality, of comprehensiveness, and of team—that we use to ground our work in this new era. The definitions below were created based on the literature, policy and practice change activities, our experience and the input of a technical advisory committee. They are meant to be more than conceptual thought pieces—we aimed to create something operational, and measureable in practice. And, they are meant to provoke discussion and encourage debate.

Comprehensiveness

Comprehensive primary care is measured by the extent to which the breadth and depth of services offered matches the most common needs of the patient panel. In comprehensive practices, patients and families experience services that meet most of their recognized and unrecognized needs—regardless of age, gender, race, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status.33 Health problems that occur with sufficient frequency to enable practitioners/teams to maintain competence should be addressed in primary care, including curative, chronic, rehabilitative, supportive, and palliative care, as well as health promotion and disease prevention. Rare or complex problems should be managed through active coordination with specialty care via periodic consultations, shared care arrangements, or long-term referrals.34

Patient-centered comprehensiveness (sometimes referred to as "whole person" comprehensiveness) recognizes that primary care teams must go beyond addressing physical needs to truly support patients in achieving health.35 Common mental health care needs, emotional and social aspects of a patient's care, and community context all must be understood and addressed. From the perspective of an individual patient, comprehensiveness is satisfied when a practice responds to all common health needs—medical, behavioral, and social.36

Breadth of care refers to the notion that comprehensive practices are responsible for addressing the large majority of health problems of its panel,37 (including prevention and wellness, acute and chronic care, management of comorbidities, gynecologic and pediatric care, rehabilitative care, and supportive and palliative care.38

Depth of care reflects that the practice provides services across the entire clinical trajectory of the common conditions and problems referenced above (where there is evidence to support it.) That includes problem recognition and diagnosis, treatment/management, including patient support, through to followup and monitoring, reassessment, and palliation (as appropriate).39

Comprehensiveness of practice support and infrastructure. Comprehensive care relies on robust practice supports and infrastructure to deliver the services described above. This includes effective care teams, information tracking systems, decision support systems for monitoring, outreach, coordination and followup, self-management support, and necessary equipment. These practice supports are also features of high-performing practices as described below.

High-Quality

A high-quality primary care practice has both the infrastructure and practice competencies to deliver services that optimize patients' health and health care experiences, while spending wisely. The infrastructure or capacity that high-quality practices have in place includes supportive leadership, a quality improvement strategy including helpful information systems and data, defined patient panels, and skilled team-based care provision. Together, this infrastructure equips primary care practices with the competencies to:

- Use data to continuously monitor and improve quality.

- Use clinical data to identify care gaps and plan visits.

- Reach out to patients with gaps in care to remedy them.

- Proactively link patients and providers together to support continuity of care.

- Use planned visits to meet patient needs for evidence-based care and self-management support.

- Provide care that is patient-centered (understood by patients and consistent with patient values and preferences).

- Provide followup and care management services to patients that need it between visits.

- Coordinate care for patients receiving care outside the practice.

- Provide timely service to patients wanting an appointment, a question answered, a refill, etc.

The skillful, standardized performance of these activities enables practices to provide cost-effective care that optimizes patient health and patient experience.

Optimization of Patient Health. High-quality primary care indicates the extent to which the practice is delivering timely care consistent with evidence-based guidelines, and achieving benchmark levels of clinical outcomes such as symptom control (e.g., pain, depressive symptoms), disease control (e.g., HIV viral load, blood pressure), or improvements in function (e.g., return to work, better school performance).40

Optimization of Patient Experience. High-quality practices are also characterized by the extent to which they deliver patient-centered care that is consistent with patient values and preferences, involves patients in decisionmaking, ensures that patients understand communications and recommendations, and helps patients become competent self-managers of their health and illness.41

Team-Based Care

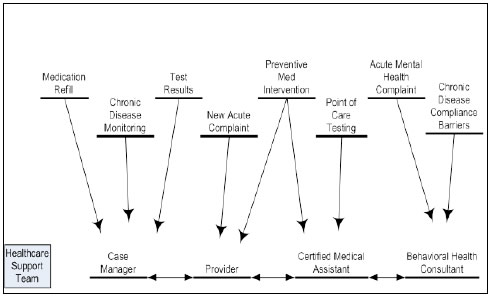

A primary care team is the providers and staff in a practice that collaborate to provide comprehensive, high-quality services to a defined panel of patients. It includes staff that work primarily with individual providers or a small group or pod of providers and their patients (the core team) as well as centralized staff that serve all providers and panels in the practice (the extended team). The latter can include employees of the practice organization or employees of collaborating organizations (e.g., academic institutions, health plans, and community agencies) who provide services in the practice. See Figure 3 for a graphic depiction of the relationship between the core and extended care team.

Figure 3. The primary care team

Primary Care Team Structure. The primary care team includes the providers and staff in a practice that provide comprehensive clinical and administrative services to the practice's clientele. In most practices of any size, the practice team includes both:

- Core teams comprised of a single provider or small group of providers and staff that collaborate with the provider(s) to serve their patient panels.

- An extended team that includes the clinical and administrative staff that collaborate with all providers and patients in the practice.

Primary Care Team Effectiveness. Effective primary care teams include individuals working at the top of their skill set, who are encouraged to operate independently, and collaborate to plan and deliver care that meets patient needs. High-functioning teams are interdependent, have shared goals, and have defined roles and work flows.42

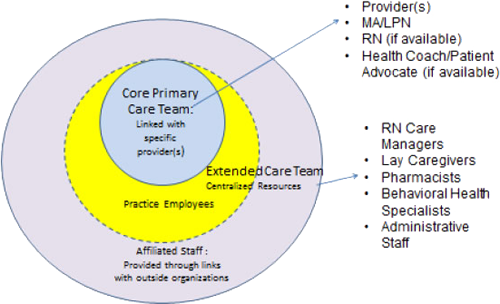

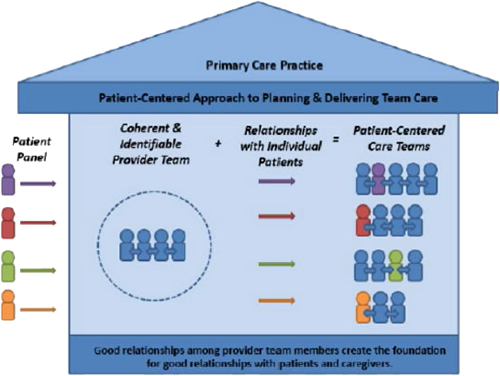

Patients as part of the Primary Care Team. The conceptual blueprint for the provision of patient-centered team-based care (see Figure 4 below, excerpted from the AHRQ White Paper: Creating Patient-Centered Team-Based Primary Care) highlights some important elements about the role of patients in team-based care.43

First, a coherent and identifiable provider team must be designed in response to the needs of the patient panel. Comprehensiveness means that the provider team responds to the most common patient needs in a given community. So it follows that different types of staff and providers make up the care team in different communities. An intentional understanding of the medical and social needs of the patient panel should shape the array of staff and providers that together make up the team. In the same way, individual patient preferences, skills, information, and agency are central to good care. Patients and their provider teams co-create health in the context of long-term relationships. The full partnership and mutual respect for the perspectives and information of both patients and care teams is crucial. Third, the unique needs of each patient may mean that a different array of individuals from the expanded care team is called upon to best partner with different patients. As patients age and as their social and medical needs change, the configuration of care providers called on to partner with them must also change. It should be noted that patients may also rely heavily on individuals outside of the organized provider care team to support their health and well-being. In the context of patient-centered care, this rich array of support is taken into account and welcomed.

Figure 4. Blueprint for provision of patient-centered team-based care

Measuring Comprehensive, High-Quality Primary Care

Over the last decade payers, employers, grant makers, community groups, and local and national government agencies have made a concerted effort to understand, measure, and evaluate high-quality, comprehensive primary care. As quality improvement efforts aimed at improving patient health outcomes by redesigning primary care practice have flourished, e.g. the Chronic Care Model, Patient-Centered Medical Home, Integrated Behavioral Health—so too has the desire to develop feasible, reliable measurement approaches for evaluating success. Led by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement and bolstered by independent efforts from the Patient-Centered Medical Home Evaluators Collaborative and others, a consensus is emerging on the value of assessing practices based on the Triple Aim of better health and better experience at a lower cost.44,45 Some have added elements of staff satisfaction and equity to these goals to make a quadruple or quintuple aim.46,47

Assessing a practice's ability to achieve the triple (or quadruple or quintuple) aim means looking at specific measures for each aim. Much work has been done through a variety of partners to develop consensus measure sets. An illustrative sample is presented below in Table 2.48 Reconciling and streamlining these measures may be helpful for practices.

Table 2. Domains of the triple, quadruple, or quintuple aim and illustrative measure examples

| Aim | Operational Outcome Measured | Measure Set Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Better health | Intermediate clinical health process & outcome measures | HEDIS, PQRS, UDS |

| Better experience | Patient Experience or Patient Satisfaction | CAHPS, Press Ganey |

| Lower cost | Per capita costs or total costs of care. Often utilization of hospital or emergency department services are measured applying standard costs to facilitate cross-region comparison | Emergency Department Use per 1,000 patients, Hospitalizations, Ambulatory Care Sensitive Admissions. |

| Improved work life for staff | Staff Experience; Staff burnout | Gallup, Baldrige, Maslach Burnout Inventory |

| Equity | Health Disparities, Social Determinants of Health | PRAPARE survey, health process and outcome metrics compared by race or SES |

As discussed above, we need more than outcomes metrics to know if a primary care is high-quality and comprehensive.49 We must also understand the infrastructure a practice has in place to make adjustments as new clinical or operational content emerges, to respond to patient needs, and to keep improving. These infrastructure measurements should focus on the capacities and competencies shown in Figure 1; those elements that we know lead to improvements in outcomes overtime. Examples of tools that assess practice infrastructure include:

- National Committee for Quality Assurance Patient-Centered Medical Home recognition (NCQA PPC-PCMH)

- The Patient-Centered Medical Home Assessment (PCMH-A)

- The Building Blocks of High-Performing Primary Care Assessment

- Primary Care Assessment Tool (PCAT)

- Assessment of Chronic Illness Care/ Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (ACIC/PACIC)

In addition to these broad tools, assessing the general capacity and functions performed in a primary care practice, AHRQ has supported efforts to consolidate and make sense of the many measures of individual capacity and function available through their Atlas' project. Examples of in-depth reports that present frameworks, definitions, and measures include:

- Care Coordination Measures Atlas

- Clinical Community Relationship Measures Atlas

- Atlas of Integrated Behavioral Health Care Quality Measures

- Atlas of Instruments to Measure Team-based Primary Care

- Mathematica Policy Research (MPR) Center on Health Care Effectiveness (CHCE) Forum: Efforts to Measure and Improve Patient-Centered Primary Care

It should be noted that the purpose—and subsequently the method—of measuring practice infrastructure and outcomes varies depending on the interested stakeholders. For each of the measures discussed above, the frequency, modality, and approach can greatly influence the findings observed. Indeed some measures (like total cost of care) may be irrelevant or impossible to capture, depending on the purpose and stakeholders.50

Conclusions

In an increasingly specialized and expensive health system, primary care has the opportunity and the mandate to reimagine high-quality, comprehensive care for the 21st century. Practices must build the capacity and develop the competencies to improve care, utilizing care teams in new ways to meet patients' needs. Many primary care practices are already experimenting with new ways of using core and extended care team members to offer more comprehensive and higher-quality care for patients. Interestingly, practices embracing team-based care are operating in urban and rural settings, integrated group practice, and independent provider offices. In practice settings where most revenue is generated through fee-for-service contracts, care teams are used to create more capacity for provider visits. In settings largely reimbursed under capitated or value-based contracts, teams support the wide range of patients' complex needs in the primary care setting, avoiding expensive and unnecessary secondary and tertiary care. Despite widely varying contexts, what is clear is that primary care teams are necessary to deliver the full range of recommended preventive, chronic, and acute care to the U.S. population.

What remains now is to understand how to optimally configure and pay for these teams. This paper provides a start with definitions and frameworks, laying the groundwork for more granular, operational models of the primary care work force that are designed to provide high-quality comprehensive care in urban and rural settings, integrated and independent practices, and for a diversity of patient needs. Deploying these model primary care teams may be a key to unlocking improved population health and well-being.

References

1. Rich E. The ACA and the Role of Health Policy in Reconstructing Primary Care: Emerging Leaders. 2014.

2. Salsberg E, Rockey PH, Rivers KL, et al. US residency training before and after the 1997 Balanced Budget Act. JAMA. 2008; 300(10), 1174-80. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.10.1174.

3. Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3), 457-502. doi: MILQ409 [pii] 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x .

4. Meyers DS, Clancy CM. Primary care: too important to fail. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(4), 272-3.

5. World Health Organization. Declaration of Alma-Ata: International Conference on Primary Health Care, Alma-Ata, USSR, 6-12. 1978.

6. Starfield B. Is primary care essential? Lancet. 1994; 344(8930), 1129-33.

7. Donaldson MS, Yordy KD, Lohr KN, et al. eds. Primary Care: America's Health in a New Era. Report of a study by a committee of the Institute of Medicine, Division of Health Care Services: National Academy Press; 1996.

8. Rich E. The Feasibility of Collecting Data on Physicians and Their Practices. 2014. http://www.mathematica-mpr.com/our-publications-and-findings/projects/the-feasibility-of-collecting-data-on-physicians-and-their-practices ![]() . Accessed April 13, 2015.

. Accessed April 13, 2015.

9. Bodenheimer T, Chen E, Bennett HD. Confronting the growing burden of chronic disease: can the U.S. health care workforce do the job? Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(1), 64-74. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.64.

10. Coleman K, Austin BT, Brach C, et al. Evidence on the Chronic Care Model in the new millennium. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(1), 75-85. doi: 28/1/75 [pii] 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.75.

11. Jackson GL, Powers BJ, Chatterjee R, et al. The patient-centered medical home: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013 Feb 5;158(3):169-78. Review. PMID: 24779044 2013;158(3), 169-78. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00579.

12. Peikes D, Zutshi A, Genevro JL. Early evaluations of the medical home: building on a promising start. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18(2):105-16.

13. The World Bank Group. Data: Health expenditure, total (% of GDP). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.EHEX.CH.ZS. Accessed April 9, 2015.

14. Petterson SM, Liaw WR, Phillips RL, et al. Projecting US primary care physician workforce needs: 2010-2025. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(6), 503-9.

15. Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) National Center for Health Workforce Analysis. Projecting the Supply and Demand for Primary Care Practitioners Through 2020. November 2013. http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/healthworkforce/supplydemand/usworkforce/primarycar....

16. IHS Inc. The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections from 2013 to 2025. Prepared for the Association of American Medical Colleges. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2015.

17. Shojania KG, Ranji SR, McDonald KM, et al. Effects of quality improvement strategies for type 2 diabetes on glycemic control: a meta-regression analysis. JAMA. 2006;296(4), 427-40.

18. Wagner EH, Coleman K, Reid RJ, et al. Guiding Transformation: How Medical Practices Can Become Patient-Centered Medical Homes: The Commonwealth Fund; 2012.

19. Sugarman JR, Phillips KE, Wagner EH, et al. The safety net medical home initiative: transforming care for vulnerable populations. Med Care. 2014;52(11 Suppl 4), S1-10. doi: 10.1097/mlr.0000000000000207.

20. Bodenheimer T, Ghorob A, Willard-Grace R, et al. The 10 building blocks of high-performing primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(2), 166-171. doi: 10.1370/afm.1616.

21. National Committee for Quality Assurance. Patient-Centered Medical Home Recognition 2014. http://www.ncqa.org/Programs/Recognition/Practices/PatientCenteredMedicalHomePCMH.aspx . Accessed April 9, 2015.

22. Peterson Center on Health Care, & Stanford Medicine Clinical Excellence Research Center. America's Most Valuable Care: Primary Care; 2014. https://med.stanford.edu/content/dam/sm/cerc/documents/2014-1203FINALMostValuableCare-PrimaryCareOverview.pdf. Accessed April 22, 2014.

23. Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, et al. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Aff. 2001;20(6), 64-78.

24. Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington DC: National Academy Press; 2001.

25. Gerteis M, Edgman-Levitan S, Daley J, et al. Through the patient's eyes: understanding and promoting patient-centered care. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1993.

26. Johnson B, Abraham M, Conway J, et al. Partnering with Patients and Families to Design a Patient- and Family-centered Health Care System: Recommendations and Promising Practices. Bethesda, MD: Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care, Institute for Healthcare Improvement, California HealthCare Foundation; 2008.

27. Scholle SH, Torda P, Peikes D, et al. Engaging Patients and Families in the Medical Home. (Prepared by Mathematica Policy Research under Contract No. HHSA290200900019I TO2.) AHRQ Publication No. 10-0083-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. June 2010.

28. Hsu C. Creating a Clinic-Community Liaison Role in Primary Care: Engaging Patients and Community in Health Care Innovation. Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute 2013, September 23. http://www.pcori.org/assets/2013/09/PCORI-Draft-Board-Meeting-Agenda-September-2013.pdf . Accessed April 22, 2014.

29. Ostbye T, Yarnall KS, Krause KM, et al. Is there time for management of patients with chronic diseases in primary care? Ann Fam Med.2005; 3(3), 209-14.

30. Yarnall KS, Pollak KI, Ostbye T, et al. Primary care: is there enough time for prevention? Am J Public Health. 2003;93(4), 635-41.

31. Newhouse RP, Stanik-Hutt J, White KM, et al. Advanced practice nurse outcomes 1990-2008: a systematic review. Nurs Econ. 2011;29(5), 230-50; quiz 251.

32. Bodenheimer TS, Smith MD. Primary care: proposed solutions to the physician shortage without training more physicians. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(11), 1881-6. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0234.

33. Starfield B. Primary Care: Concept, Evaluation, and Policy. New York: Oxford University Press; 1992.

34. O'Malley A, Rich E. Measuring Comprehensiveness of Primary Care: Report. Mathematica Policy Research; 2014.

35. Haggerty JL, Beaulieu MD, Pineault R. Comprehensiveness of care from the patient perspective: comparison of primary healthcare evaluation instruments. Healthc Policy. 2011; 7(Spec Issue), 154-66.

36. Dickinson WP, Miller BF. Comprehensiveness and continuity of care and the inseparability of mental and behavioral health from the patient-centered medical home. Fam Syst Health. 2010; 28(4), 348-55. doi: 10.1037/a0021866.

37. Essays UK. Concept Of Primary Health Care in Nigeria. 2013. http://www.ukessays.com/essays/health/concept-of-primary-health-care-in-nigeria.php?cref=1 . Accessed May 13, 2015.

38. Kringos DS, Boerma WG, Hutchinson A, et al. The breadth of primary care: a systematic literature review of its core dimensions. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10, 65. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-65.

39. Owolabi O, Zhang Z, Wei X, et al. (). Patients' socioeconomic status and their evaluations of primary care in Hong Kong. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13, 487. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-487.

40. National Committee For Quality Assurance. The Essential Guide to Health Care Quality. Washington, DC: NCQA.

41. United States Senate. Committee on Finance, Subcommittee on Health Care. What is Health Care Quality and Who Decides? 2009. (Statement by Carolyn M. Clancy, MD, Director, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality).

42. Gittell JH. New directions for relational coordination theory. In: Cameron K, Spreitzer G, eds., The Oxford Handbook of Positive Organizational Scholarship. Oxford University Press; 2011.

43. Schottenfield K, Peterson D, Peikes D, et al. White Paper: Creating Patient-Centered Team Based Primary Care. AHRQ Publication No. 16-0002-EF (pending publication). Rockville MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Forthcoming.

44. Institute for Healthcare Innovation (IHI). The IHI Triple Aim Initiative: Better Care for Individuals, Better Health for Populations, and Lower Per Capita Costs. http://www.ihi.org/engage/initiatives/TripleAim/Pages/default.aspx Accessed May 13, 2015.

45. Rosenthal MB, Abrams MK, Bitton A. Recommended Core Measures for Evaluating the Patient-Centered Medical Home: Cost, Utilization, and Clinical Quality. New York: Commonwealth Fund pub. 2012;1601;12.

46. Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6), 573-6. doi: 10.1370/afm.1713.

47. Wagner EH. The Fourth Aim: Primary Care and the Future of American Medical Care. Dallas, TX: IHI Office Practice Summit; 2012.

48. Institute of Medicine. Vital Signs: Core Metrics for Health and Health Care Progress. Washington, D.C: The National Academies Press; 2015.

49. Goldman RE, Parker DR, Brown J, et al. Recommendations for a mixed methods approach to evaluating the patient-centered medical home. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(2), 168-75. doi: 10.1370/afm.1765.

50. Coleman K, Phillips KE, Van Borkulo N, et al. (2014). Unlocking the black box: supporting practices to become patient-centered medical homes. Med Care, 52(11 Suppl 4), S11-17. doi: 10.1097/mlr.0000000000000190