Understand the Science of Safety

Facilitator Notes

Contents

- Slide 1. Cover Slide

- Slide 2. Learning Objectives

- Slide 3. Putting Safety into Context

- Slide 4. Health Care Defects

- Slide 5. How Can These Errors Happen?

- Slide 6. The Science of Safety

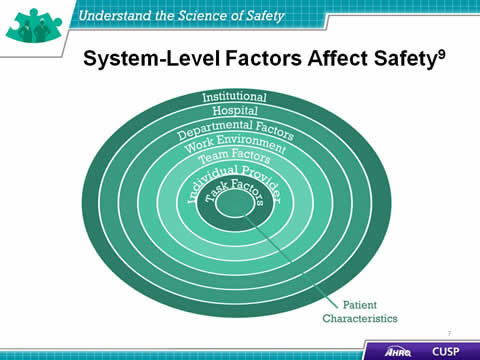

- Slide 7. System-Level Factors Affect Safety9

- Slide 8. Safety is a Property of the System

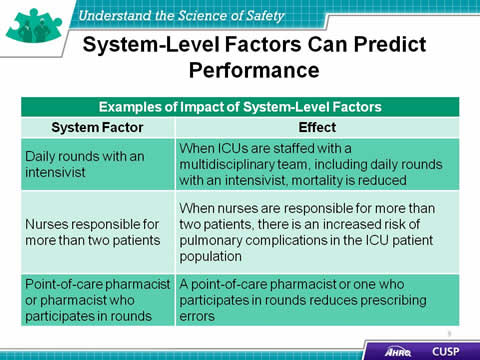

- Slide 9. System-Level Factors Can Predict Performance

- Slide 10. Three Principles of Safe Design

- Slide 11. Standardize When You Can

- Slide 12. Create Independent Checks

- Slide 13. Learn From Defects

- Slide 14. Exercise

- Slide 15. Principles of Safe Design Apply to Technical Work and Teamwork

- Slide 16. Technical Work and Teamwork

- Slide 17. Exercise

- Slide 18. Teams Make Wise Decisions When There is Diverse and Independent Input

- Slide 19.How To Ensure Diverse and Independent Input

- Slide 20. Basic Components and Process of Communication11

- Slide 21. Diverse and Independent Input

- Slide 22. Reduced CRBSI By Applying Principles of Safe Design12

- Slide 23. Understand the Science of Safety: What the Team Must do

- Slide 24. Summary

- Slide 25. CUSP Tools

- Slide 26. TeamSTEPPS Tools1

- Slide 27. References

- Slide 28. References

- Slide 29. References

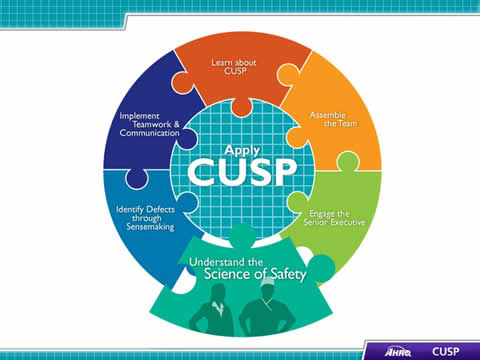

Slide 1: Cover Slide

Say:

The “Understand the Science of Safety” module of the Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program (or CUSP) Toolkit discusses the importance of understanding system design, safe design principles, and valuing diverse input from team members. By analyzing patient safety as a science, frontline providers will provide a higher quality of patient-centered care on their hospital unit.

[D] Select for Text Description.

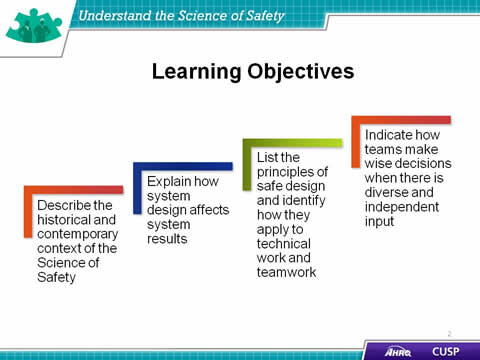

Slide 2: Learning Objectives

Say:

In this module, we will:

- Describe the historical and contemporary context of the Science of Safety,

- Explain how system design affects system results,

- List the principles of safe design and identify how they apply to technical work and teamwork, and

- Detail how teams make wise decisions when there is diverse and independent input.

[D] Select for Text Description.

Slide 3: Putting Safety in Context

Say:

Advances in medicine have led to positive outcomes, including:

- Most childhood cancers are curable,

- AIDS is now a chronic disease, and

- Life expectancy has increased 10 years since the 1950s.

These incredible advancements have enhanced the quality of life for patients and their families. Yet, despite these advancements, our health care system is still plagued with defects that limit the quality of care patients receive.

[D] Select for Text Description.

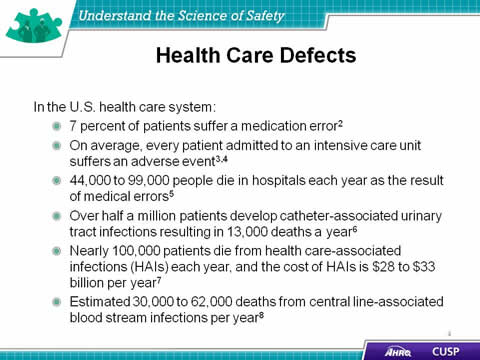

Slide 4: Health Care Defects

Say:

Examples of the effect of defects and errors in the U.S. health care system are illustrated on this slide:

- 7 percent of patients suffer from a medication error.

- On average, every patient admitted to an intensive care unit suffers an adverse event.

- 44,000 to 99,000 people die from medical errors in hospitals each year.

- Over half a million patients develop catheter-associated urinary tract infections, resulting in 13,000 deaths a year.

- Nearly 100,000 patients die from healthcare-associated infections each year, and the cost of these infections is $28 to $33 billion per year.

- Nearly 100,000 patients die from healthcare-associated infections each year, and the cost of these infections is $28 to $33 billion per year.

[D] Select for Text Description.

Slide 5: How Can These Errors Happen?

Say:

Errors occur within the health care setting because people are fallible.

Providers, executives, and managers need to understand why errors occur. The first step in comprehending why they happen is accepting the fact that people are not perfect. Even the most knowledgeable and experienced provider is influenced by the environment in which he or she works and can be responsible for mistakes that inflict harm to a patient and that patient’s family. In understanding and acknowledging this fallibility, individuals can redesign care and delivery processes to improve patient care.

Errors occur because medicine is still treated as an art, not a science.

In analyzing how errors occur, frontline providers must recognize the scientific nature of medicine. By treating medicine and care delivery as a science instead of an art, providers can scrutinize their processes using evidence-based practices. As a result, providers must increase their ability to learn from mistakes and implement procedures to help prevent serious errors from occurring again.

Errors also occur because systems frequently do not catch mistakes before they reach the patient.

Standardizing procedures, such as applying checklists and creating independent assessments for key processes, further aids in the development of high-quality patient care by allowing providers to mitigate risks before a harmful event takes place.

[D] Select for Text Description.

Slide 6: The Science of Safety

Say:

According to the Science of Safety:

- Every system is perfectly designed to achieve its end results. Once all team members, including managers and executives, understand that systems are designed to achieve specific results, they are better prepared to join system improvement activities for reducing patient harm. Being cognizant of the system design and how it contributes to the results that it delivers will help providers adapt their routines and procedures to meet the needs of the unit.

- In addition, safe design principles must be applied to technical work and teamwork to maximize results. The three principles of safe design are (1) standardize when possible, (2) create independent checks, and (3) learn from defects. The principles of safe design are discussed in more detail later in this module.

- Last, teams make intelligent decisions when provided with diverse and independent input from all team members, reflecting their roles and experience, which supports the relationship between patient safety and system design.

[D] Select for Text Description.

Slide 7: System-Level Factors Affect Safety9

Say:

As the illustration shows, at any given time, there are several system factors that simultaneously influence unit culture and patient safety.

Patient characteristics

Patient characteristics, such as medical history, acuity, primary language, or ability to participate in the development of the care plan, can influence patient safety.

Task factors

In addition to patient characteristics, task factors can shape the delivery of care and patient safety in the unit. Patient complexity influences both the ability of providers to meet patient needs and their capacity to manage the task of care. Complex wound management, for example, not only requires specific staff knowledge and skill but also may take time away from performing tasks for other patients both efficiently and effectively.

Individual provider

Providers should understand the relationship between their own knowledge, skills, and attitudes and how these may affect the quality of care that patients receive. Providers should be comfortable speaking up if they do not agree with task assignments and protocols or when they see patient safety risks. Evidence suggests a direct relationship between some patient outcomes and the willingness of staff to speak up.

Team factors

Team factors may involve issues with teamwork, communication, inadequate supervision, and training.

Work environment

Noisy, dirty, distracting, or poorly lit work environments can wreak havoc on the delivery of high-quality patient care and should be addressed when attempting to diagnose system-level influences on patient care.

Departmental factors

When staffing issues, admission policies, and protocols prove to be insufficient for the needs of the patient and the provider, they will affect the quality of care. Staffing and coverage shortages cause patients to suffer because they do not receive the attention they need to recover. Additionally, staffing and coverage issues increase the likelihood of medication or procedure errors, degrading the type of care the patient receives.

Hospital and institutional factors

The type of facility and budgetary limitations may affect the patient’s care plan. While these issues are the furthest removed from the patient in the diagram, these factors continually affect patient care during the hospital recovery period.

[D] Select for Text Description.

Slide 8: Safety is a Property of the System

Do:

Play the video.

Ask:

- What hospital pressures were identified in the video?

- What work environment factors were identified in the video?

[D] Select for Text Description.

Slide 9: System-Level Factors Can Predict Performance

Say:

As the table demonstrates, daily rounds with an intensivist encourage the development of a multidisciplinary team to reduce unit-wide mortality. When nurses are responsible for more than two patients, there is an increased risk of patient complications. When the point-of-care pharmacist participates in rounds, medication prescribing errors are reduced.

In an example from a CUSP team working on an obstetrics unit, hierarchy issues plagued the unit, disrupting the abilities of the unit nurses and doctors to work together effectively. The nurses were able to alleviate these hierarchical issues by engaging hospital administration with their initiative. With the support of the executive staff at their hospital, the nurses were empowered to enforce the delivery and induction guidelines set by the facility. This shift of authority led to a significant drop in the number of reported birth complications.

[D] Select for Text Description.

Slide 10: Three Principles of Safe Design

Say:

Three principles of safe design are:

- Standardize when possible,

- Create independent checks, and

- Learn from defects.

These principles sculpt the means with which unit teams are able to scrutinize their environment and the processes to deliver safety patient care.

Standardize when possible

In standardizing procedures, unit teams are able to alleviate duplications of labor and resources. This in turn will save unit teams valuable time and energy when working on their quality improvement projects. Examples from CUSP teams include the use of checklists and the provision of standardized staff training.

Create independent checks

Independent checks help guarantee the patient receives the highest quality of care possible. Independent checks include checklists and protocols that help unit teams standardize care and procedures on their unit. Examples created by CUSP teams in larger hospitals include medication stop orders and the installation of a preterm delivery protocol. CUSP teams are able to focus on patient care and have confidence that any accidental breach in protocol will be caught by a check or team alert when the break in policy or procedure occurs.

Learn from defects

This principle calls for unit teams to evaluate their processes and learn from defects and, when possible, to share what they learn with other similar care settings. When learning from defects, unit teams identify:

- What happened?

- Why did it happen?

- What will we do to reduce the recurrence?

- How will we know it worked?

In determining the defect that occurred, teams reconstruct the timeline of the event by placing themselves in the midst of the incident as it unfolded. Analyzing what happened and why it happened helps the team understand the contributing factors and processes. Through proposing, prioritizing, and implementing solutions, unit teams seek to minimize the chances the defect will reoccur.

Unit-wide assessment of the effectiveness of the interventions allows the team to ensure effective solutions are sustained, ineffective solutions are revised, and frontline staff members are aware their input is critical to continual quality improvement as embodied by the Learning From Defects exercise.

[D] Select for Text Description.

Slide 11: Standardize When You Can

Do:

Play the video.

Ask:

- What are some ways you standardize work in your unit?

- What has worked well? Why?

- What has not worked well? Why?

[D] Select for Text Description.

Slide 12: Create Independent Checks

Do:

Play the video.

Ask:

- What issues did the team experience in its unit?

- How did the team implement independent checks in its unit?

- What are some ways your team carries out independent checks?

[D] Select for Text Description.

Slide 13: Learn From Defects

Do:

Play the video.

Say:

Apply these four Learning From Defects questions to this example.

- What happened?

- Why did it happen?

- How will you reduce the risk of recurrence?

- How will you know it worked?

[D] Select for Text Description.

Slide 14: Exercise

Say:

Think about a recent safety issue in your unit and answer the four Learning From Defects questions.

[D] Select for Text Description.

Slide 15: Principles of Safe Design Apply to Technical Work and Teamwork

Say:

The principles of safe design apply to technical work as well as teamwork.

Standardize when you can

Standardize to eliminate unnecessary or repetitive steps and simplify processes for complying with evidence or protocols. In an example from an obstetrics unit, staff received standardized education on the prevention of post-partum hemorrhages and implemented a pre-operation checklist for the emergency room unit to prepare a patient for emergency surgery. Both provide simple solutions to issues that affected the quality of care that patients received within their hospital units.

Create independent checks

Creating independent checks can range from increasing regulation to streamlining workflow processes within units. These independent checks can prevent unnecessary procedures and medication errors that result in patient harm on the unit.

One example, from the “Create Independent Checks” video, comes from an obstetrics unit that implemented CUSP to decrease the number of elective pre-term deliveries on their unit. This unit had a high level of elective labor inductions before the 39th week of pregnancy. While some of these elective procedures were medically necessary, others were not, resulting in a baby being delivered and immediately separated from its mother to stay on another unit.

Recognizing an opportunity for improvement, nurses on this unit created a “39 week rule” from which all labor inductions were required to take place on or after the 39th week of pregnancy if the mother was healthy. The nurses employed charts and an induction registration process, which encouraged unit physicians to schedule their inductions while providing nurses with an opportunity to stop procedures that did not meet the criteria.

This independent check helped decrease the number of infants requiring additional care because they were delivered before the 39th week of pregnancy.

[D] Select for Text Description.

Slide 16: Technical Work and Teamwork

Do:

Play the video

Say:

Identify the technical work and teamwork components in the following examples from the video:

- Using daily goals,

- Post-partum hemorrhage kit, and

- Obstetrics unit example.

[D] Select for Text Description.

Slide 17: Exercise

Ask:

How do you see technical and adaptive work fitting in your unit?

[D] Select for Text Description.

Slide 18: Teams Make Wise Decisions When There is Diverse and Independent Input

Say:

Teams make wise decisions when there is diverse and independent input from unit providers, colleagues, patients, and patients’ family members.

[D] Select for Text Description.

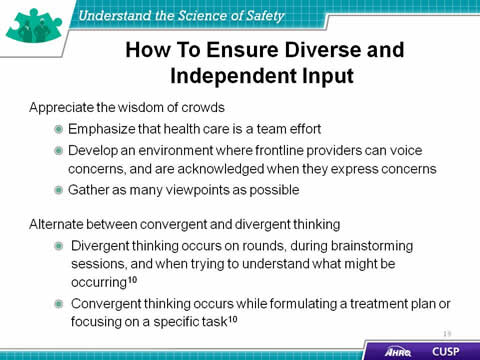

Slide 19: Exercise

Say:

Providers must remember that health care is a team effort and operates best when all team members are ready, willing, and able to commit to delivering the highest quality patient care. Team members should strive to build an environment in which frontline providers feel comfortable speaking up and having their concerns addressed. The backgrounds, experience, and training of unit staff varies greatly, and incorporating this diversity in the CUSP initiative will prove to be an effective means of delivering high-quality patient care.

For more information about engaging a diverse array of unit team members to participate in your initiative, please review the “Assemble the Team” module of the CUSP Toolkit.

Team members need to alternate between convergent and divergent thinking.

Convergent thinking

Convergent thinking asks the team to confer about all the potential problems that have been discussed and collaborate to form a plan of treatment, a plan of care for the day, or a plan to eliminate an identified defect.

Divergent thinking

Divergent thinking tends to occur during rounds but is not limited to this activity. It includes brainstorming and possibility thinking to explore questions such as:

- What is the patient’s current status?

- If there seem to be complications, what might be happening?

- What might be important to consider?

- Did we miss anything?

- What will be the outcome of decisions we make regarding these issues?

[D] Select for Text Description.

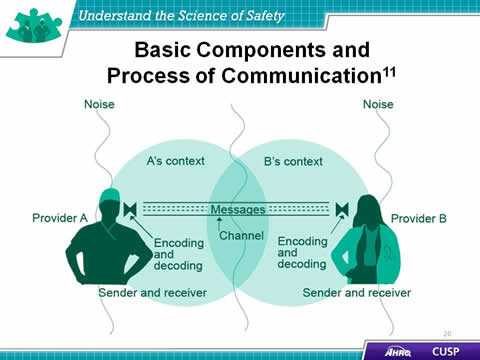

Slide 20: Basic Components and Process of Communication11

Say:

Communication, in both verbal and nonverbal forms, is complex and subject to distortion and misinterpretation. In verbal communication, ideas are first encoded, or created, when the sender relays a message with meaning to the receiver. The receiver then decodes, or understands, the message received. However, that understanding is affected by the context surrounding the message, noise and other distractions, and the individual makeup of the participants involved in the conversation.

These seemingly insignificant components comprise the overall communication system in which providers share information, ideas, and needs within the health care setting. Each element is interconnected, meaning a distraction or malfunction in encoding or any other component in the model greatly affects decoding and understanding.

The background and physical environment of the communicators influences the distribution and receipt of messages. Being aware of these factors will help CUSP teams develop environments that facilitate communication and feedback among team members.

Developing supportive environments in which unit teams will be able to discuss ideas, plans, and programs will contribute greatly to the success of the CUSP initiative for the unit. Teamwork and communication is discussed in greater detail in the “Implement Teamwork and Communication” module of the CUSP Toolkit.

[D] Select for Text Description.

Slide 21: Diverse and Independent Input

Do:

Play the video

Ask:

- What did the team identify as the benefits of having a team with diverse and independent input?

- What steps would you take to ensure having a team with diverse and independent input?

[D] Select for Text Description.

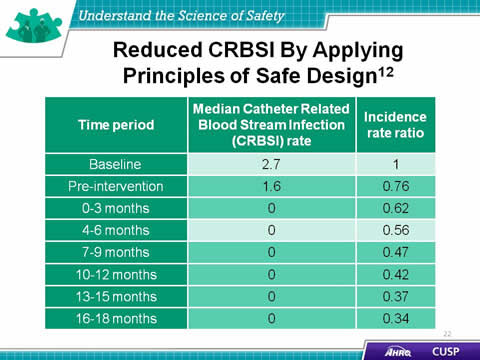

Slide 22: Reduced CRBSI By Applying Principles of Safe Design12

Say:

Applying the principles of safe design to quality improvement initiatives increases the likelihood for success. CUSP was successfully used in the Michigan Keystone Center for Patient Safety and Quality’s CRBSI (which stands for catheter-related blood stream infection) reduction project and brought about the following achievements:

- Unit teams virtually eliminated CRBSI across the State of Michigan;

- The median CRBSI rate was reduced to zero;

- Teams were able to sustain a median CRBSI rate of zero for nearly 4 years after the start of the intervention; and

- The incidence rate ratio of CRBSI decreased over time.

[D] Select for Text Description.

Slide 23: Understand the Science of Safety: What the Team Must do

Say:

The team and hospital staff members will need to view the “Science of Safety” video. To begin, create a roster of all hospital staff, executives, and providers, then invite these individuals to attend a screening of the “Science of Safety” video.

[D] Select for Text Description.

Slide 24: Summary

Say:

To review the main components of this module, consider these thoughts:

- Every system is designed to achieve its anticipated results.

- The principles of safe design are standardize when you can, create independent checks, and learn from defects.

- The principles of safe design apply to technical work and teamwork.

- Teams make wise decisions when there is diverse input.

[D] Select for Text Description.

Slide 25: CUSP Tools

Say:

In addition to the information presented in this module, CUSP tools are available online on the AHRQ Web site at www.ahrq.gov/cusptoolkit/.

Some of the teamwork tools that will help the unit team understand the science of safety include:

Daily Goals Checklist

The Daily Goals Checklist is a care plan for patients that prompts facility staff to focus on what must be accomplished that particular day to safely move the patient closer to discharge. The purpose of this tool is to improve communication among the unit team, patients, and family members.

Morning briefing

A morning briefing is a conversation between two or more people using concise and relevant information to endorse effective communication and planning before rounds in the hospital unit. This tool provides physicians and nurses with a structured approach to review problems that may have occurred during the previous shift, assess the anticipated workload for the coming shift (such as new patients, patient discharges, and patient procedures), and create a communication plan to address any identified issues that may happen during the day. Unit teams can complete this tool together each morning during patient rounds.

Shadowing

The Shadowing Another Professional Tool offers a method to examine and understand the cultural differences that exist among various professions. The individuals who shadow and who are shadowed may vary based on the specific unit challenges. Executives, physicians, nurse managers, infection preventionists, bedside clinicians, and unit support staff all approach issues very differently. The shadowing process allows individuals to experience the work culture of their colleagues and gain a deeper appreciation for the demands and challenges of each role.

Observing patient care rounds

Evidence suggests that teamwork and communication affect both staff morale and patient care delivery. Observing rounds is a process to objectively gauge and improve teamwork dynamics across and between disciplines, to identify areas in which communication could be more explicit in setting daily patient goals, and to provide a method to continually build communication skills.

Team Check-up Tool

The Team Check-up Tool provides a standardized method for engaging in discussions about culture within the hospital. Unit teams first assess culture before starting an intervention, then use feedback from frontline providers to identify potential barriers to overcome, as well as strengths that can be better used. This tool can be used to target a goal for improvement shortly after the culture assessment and then every 3 to 6 months, or as needed, to initiate culture conversations, evaluate cultural issues (between survey administrations), and monitor the progress of culture change.

[D] Select for Text Description.

Slide 26: TeamSTEPPS Tools1

Say:

The TeamSTEPPS® tools relevant to CUSP are:

- Brief

- Huddle

- Debrief

- SBAR

- Check Back

- Call Out

- Hand Off

- I PASS the BATON

- DESC Script

Please see the “Implement Teamwork and Communication” module in this toolkit for more information about these TeamSTEPPS tools.

[D] Select for Text Description.

Slide 27: References

Say:

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Department of Defense. TeamSTEPPS. Available at http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/education/curriculum-tools/teamstepps/index.html.

- Bates DW, Cullen DJ, Laird N, et al. Incidence of adverse drug events and potential adverse drug events. JAMA. 1995;274(1):29-34.

- Donchin Y, Gopher D, Olin M, et al. A look into the nature and causes of human errors in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 1995;23:294-300.

- Andrews LB, Stocking C, Krizek T, et al. An alternative strategy for studying adverse events in medical care. Lancet. 349:309-313,1997.

[D] Select for Text Description.

Slide 28: References

Say:

- Kohn L, Corrigan J, Donaldson M. To err is human: building a safer health system. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1999.

- Scott, RD. The Direct Medical Costs of Healthcare-Associated Infections in U.S. Hospitals and the Benefits of Prevention. March 2009. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dhqp/pdf/Scott_CostPaper.pdf

- Klevens M, Edwards J, Richards C, et al. Estimating Health Care-Associated Infections and Deaths in U.S. Hospitals, 2002. PHR. 2007;122:160-166.

- Ending health care-associated infections, AHRQ, Rockville, MD, 2009. http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/factsheets/errors-safety/haicusp/index.html

- Vincent C, Taylor-Adams S, Stanhope N. Framework for analysing risk and safety in clinical medicine. BMJ. 1998;316:1154–57.

[D] Select for Text Description.

Slide 29: References

Say:

- Heifetz R. Leadership without easy answers, president and fellows of Harvard College. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press;1994.

- Dayton E, Henriksen K. Communication failure: basic components, contributing factors, and the call for structure. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007;33(1): 34-47.

- Pronovost P, Needham D, Berenholtz S, et al. An intervention to decrease catheter-related bloodstream infections in the ICU. New Engl J Med. 2006;355(26):2725-32.

[D] Select for Text Description.