How are CHIPRA quality demonstration States testing the Children's Electronic Health Record Format?

Evaluation Highlight No. 10

Author: Leslie Foster

Contents

| The CHIPRA Quality Demonstration Grant Program In February 2010, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) awarded 10 grants, funding 18 States, to improve the quality of health care for children enrolled in Medicaid and the Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP). Funded by the Children's Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2009 (CHIPRA), the Quality Demonstration Grant Program aims to identify effective, replicable strategies for enhancing quality of health care for children. With funding from CMS, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) is leading the national evaluation of these demonstrations. The 18 demonstration States are implementing 52 projects in five general categories:

|

This Evaluation Highlight is the 10th in a series that presents findings from the Children's Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2009 (CHIPRA) Quality Demonstration Grant Program. Two States—North Carolina and Pennsylvania—are part of an effort to test the Children's Electronic Health Record (EHR) Format (the Format), which was commissioned by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and intended to improve the quality of health care for children enrolled in Medicaid and CHIP. The Highlight focuses on the States' activities from 2012 to early 2014.

Key Messages

- State and provider stakeholders in North Carolina and Pennsylvania generally agreed that the Format addresses many child-specific functions not addressed by current EHRs. (The current version of the Format is available at http://ushik.ahrq.gov/mdr/portals.)

- Practices and health systems discovered that their EHRs did not meet many Format requirements, although some requirements were available through the purchase of an EHR upgrade. When requirements were already present in EHRs but could not be accessed readily, the Format drove discussions about the needs and expectations of EHR users.

- Incorporating the Format requirements into current EHRs was challenging. Pennsylvania health systems prioritized the changes they would try to make to their EHRs, whereas EHR coaches in North Carolina chose to focus on training practices to improve their use of EHRs.

- State, health system, and practice staff in North Carolina and Pennsylvania said that EHR vendors were reluctant to engage in their projects because of other priorities.

- An EHR certification module for child health, even if limited to a subset of high-priority Format requirements, could help spur desired change in child-specific EHR functionality.

Background

Health care providers, payers, and Federal and State policymakers increasingly look to EHRs as a tool for measuring and improving health care quality. However, existing EHRs do not fully support the provision of high-quality care to children from prenatal development through adolescence.1,2 For example, weight-based medication dosing, immunization tracking, and monitoring of children's growth against standardized charts are routine clinical practices that many EHRs do not fully support.

In 2009, the reauthorization of CHIP specifically required the development of a Children's EHR Format and thus became an impetus for change. CMS funded and collaborated with AHRQ on a development process that drew on existing work and specifications in children's health information technology (IT) and the contributions of health IT and child health informatics experts.

The resulting Format is a set of recommended requirements for EHR data elements, data standards, usability, functionality, and interoperability. The Format's current set of 700 requirements is sorted into 21 topic areas relevant to the care of children in ambulatory or inpatient settings. Topic areas include prenatal and newborn screening, immunizations, growth data, children with special health care needs, well-child/preventive care, patient portal availability, medication management, and the reporting of child abuse. The individual requirements in each topic are prioritized by whether they shall, should, or may be present in EHRs.

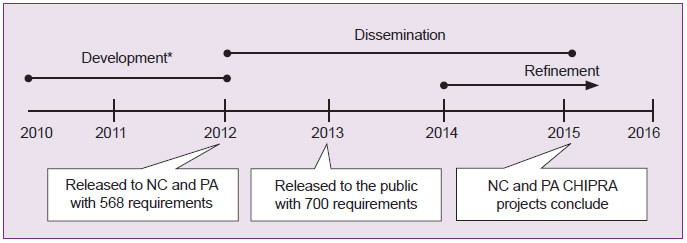

This Highlight focuses on the roles of North Carolina and Pennsylvania in the Format's evolution (Figure 1). Both States are using CHIPRA quality demonstration grant funds to test (1) how well the Format's requirements support the provision of primary care to children and (2) how readily the requirements can be incorporated into existing EHRs. The information in this Highlight comes from semi-structured interviews conducted by the national evaluation team in spring 2012 and spring 2014. The team interviewed each State's CHIPRA quality demonstration staff and the staff of participating health systems and primary care practices.

Figure 1. Evolution of the Children's EHR Format

Note: AHRQ and CMS are responsible for the development and refinement of the Format.Refinements identified during a contract ending in late 2015 may be implemented later.

Findings

The two States took different approaches to testing the usability and functionality of the Format. Pennsylvania tested it with five health systems that serve children: three children"s hospitals and affiliated ambulatory practice sites, one federally qualified health center (FQHC), and one small hospital. North Carolina used EHR "coaches" to reach out to 30 individual practices about testing the Format (Table 1).

Table 1. Overview of Health Systems and Practices Testing the Format, as of Spring 2014

| State | Provider Types | Prior EHR Experience | Total Number of EHRs in Usea | Service Areas |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pennsylvania | 3 children's hospitals and affiliated ambulatory practice sites 1 FQHC 1 small hospital |

Not required | 4 | Statewide Rural, urban, and suburban |

| North Carolina | 30 independent pediatric or family practices | Required | 6 | Statewide Rural, urban, and suburban |

FQHC = federally qualified health center

a The EHRs are sold by vendors offering products that are certified under the CMS EHR Incentive Program.

Pennsylvania's health systems worked independently

Pennsylvania gave the five health systems freedom to test the Format as they saw fit and designated one of the children's hospitals to support and loosely organize the work of the other four systems. Accordingly, each system developed its own project objectives and implementation plans and reported to the State on their progress and setbacks. The State gave the systems this much leeway because the extent of their experience with EHRs varied widely; some systems had a great deal of experience, while others had very little.

North Carolina used EHR coaches to recruit and guide practices

North Carolina hired, trained, and supervised four EHR coaches whose professional backgrounds ranged from nursing to practice management to health IT. According to project stakeholders, the coaches' interpersonal skills and knowledge of health care have been especially germane to the coaching job.

Each coach recruited practices in an assigned area of the State to test the Format. Coaches oversaw the completion of a survey that asked practices and EHR vendors to compare existing EHRs to the Format. The coaches also have acted as a liaison between practices and vendors in considering next steps, and they have begun training practices to use EHR functionalities that already meet Format requirements.

| "For the practices, [the Format] is about having a better EHR system. The practices have a lot of angst about the systems they are currently using. Their EHR may be missing an asthma action plan and a growth chart. It's missing key things they need."

—North Carolina Demonstration Staff, May 2014 |

Practices and health systems were motivated by a desire for better EHRs

Practices in North Carolina and health systems in Pennsylvania joined the CHIPRA quality demonstration either because they were dissatisfied with their EHRs' capacity for supporting high-quality children's health care, because they saw the CHIPRA quality demonstration as an opportunity to improve their EHRs, or both. Practices and health systems viewed the Format as a tool for learning more about their EHRs, and they used the CHIPRA quality demonstration as a structure through which they could communicate their unmet needs to vendors.

In addition, North Carolina practices were drawn to the project by the opportunity to work with EHR coaches, do their own reporting for quality improvement, and participate in a health information exchange. Pennsylvania's health systems received grant funds for their work, and they could also receive incentive payments for using their EHRs to report and improve their performance on certain quality measures as part of the State's CHIPRA quality demonstration project (Highlight 5).3

Stakeholders reported that the Format improves on existing EHR products

In both States, CHIPRA quality demonstration staff, project managers, and providers involved in testing the Format said that it is comprehensive and that it reflects a solid understanding of the delivery of children's health care. North Carolina practices rated approximately 80 percent of the requirements they reviewed as medically relevant. Nonetheless, they also reported that many requirements are ambiguous or lacking in detail, and they believe that vendors might need to consult clinicians and quality experts in order to fully understand the requirements. In addition, during the comparison phase of their projects (described below), the smaller Pennsylvania health systems began to view the Format as exceeding their EHR needs and wished it had been narrowed to a much smaller set of core requirements.

Comments from providers about specific requirements (or missing requirements) varied enough that no common themes emerged from their responses. For example, a few providers said they appreciated the Format's decision-support requirements, noting that the requirements contain detailed information that providers need but usually do not memorize. Two providers wanted the Format to include a way to identify siblings in their practices so that they could better address the health needs of families.

The providers' opinions about the Format's requirements for linkages to school-based health data systems were mixed. Some wanted information about school-based care in their EHRs but doubted that the necessary interoperability would exist in the near future. Others said that their EHR is a record of care provided by their practice alone and should not contain external information.

North Carolina and Pennsylvania used different approaches to engage vendors

North Carolina wants its project not only to improve the health IT industry's understanding of the role of technology in children's health care but also to accomplish change at the vendor-product level. To that end, CHIPRA quality demonstration staff asked EHR vendors to agree to (1) complete and return a survey that compared existing products to the Format, (2) train EHR coaches to use EHR features that practice staff were not familiar with, and (3) indicate whether their products will meet specific Format requirements in the foreseeable future. By spring 2014, four of six targeted vendors agreed to participate in the North Carolina project. With the CHIPRA quality demonstration scheduled to end in February 2015, practices that work with the remaining two vendors may not get the training or the EHR enhancements they hoped for.

EHR vendors have no formal role in the Pennsylvania project. Some of the health systems involved their vendors when they compared the Format to their own EHR systems. Other health systems did not try to involve their vendors until they reached the stage of determining how to incorporate Format requirements into their systems.

| "The requirements are very specific and may be located in hundreds of locations in different templates and different types of visits throughout the EHR system. That probably took the most time at first—just deciding if your system does it or not."

—Pennsylvania Physician, May 2014 |

Comparing the Format to existing EHRs was challenging but valuable

Over a course of several months, North Carolina practices, Pennsylvania health systems, and some vendors in each State compared the Format to existing EHRs one requirement at a time in order to identify gaps between the two.

Tackling complexity. The director of the North Carolina CHIPRA quality demonstration project prioritized 133 of the Format's requirements that she considered most relevant to the State's quality improvement goals in the following areas: developmental and behavioral health; obesity; oral health; asthma; and the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment (EPSDT) program in Medicaid. Focusing on only the 133 prioritized requirements, the practices and vendors independently completed the survey mentioned earlier (Table 2). EHR coaches compiled and compared the responses of practices and vendors. Pennsylvania health systems answered similar questions about the requirements, but the State gave them all 568 requirements at once and did not explicitly require responses from practices and vendors to be collected or compared.

Table 2. Process for Comparing the Children's EHR Format to Existing EHRs

| Requirement | Questions for Practices | Question for EHR Vendors | Possible Next Step | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Is the requirement medically relevant? | Does your EHR meet the requirement? | If so, does your practice use it? | Does your company's EHR product meet the requirement? | ||

| 1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No change to existing EHR |

| 2 | Yes | No | N/A | Yes—in upgrade | Consider purchasing upgrade |

| 3 | Yes | No | N/A | Yes | Training opportunity |

| 4 | Yes | No | N/A | No | IT solution |

| 5 | No | Yes or no | N/A | Yes or no | No change to existing EHR; feedback for Format refinement |

Notes: This table simplifies North Carolina's approach for illustrative purposes. N/A = not applicable.

Reaching agreement. Practices and health systems had to resolve many disagreements with vendors about whether EHRs met Format requirements. A Pennsylvania project manager estimated that his health system disagreed with its vendor on 30 to 40 percent of the requirements, and the two parties spent 15 hours comparing the results of their assessments and resolving discrepancies.

Possible next steps varied with the reason for the disagreement. For example, if a practice noted that its EHR did not meet a requirement, but a vendor indicated that an upgraded version would meet the requirement, then the practice could consider an upgrade as a next step (Table 2, row 2). In many other cases, lack of clarity over the same version of an EHR arose because a practice was not fully aware of all features of its EHR. In such cases, additional training of EHR users could be the next step for a practice or health system to consider (Table 2, row 3).

| "The model Format becomes the engine of explaining what a good pediatric EHR system should contain and what it can do for you."

—North Carolina Demonstration Staff, May 2014 |

Realizing benefits. Practices and health systems said that they benefited from the comparison process. For instance, they learned more about the capabilities of their EHRs. Moreover, they were not satisfied to learn that their EHR met a requirement technically unless it also fit into an intuitive, efficient workflow. Thus, the comparison process was also beneficial in that it gave practices and health systems the chance to use the Format to drive discussions about their needs and expectations.

Health systems and practices have begun incorporating Format requirements

After the comparison phase, health systems and practices considered how to more closely align their EHRs with the Format requirements.

Setting priorities to add requirements. One of the larger Pennsylvania health systems (a major children's hospital with a network of ambulatory practices) is working to incorporate requirements from most of the Format's 21 topic areas into its EHR. Considering the 100 or so requirements that the system's EHR did not meet, the system staff prioritized each requirement according to whether it (1) was related to patient safety, (2) was developmentally appropriate and patient focused, (3) described a function that would be easy to use, and (4) was realistic to incorporate from a practical standpoint (taking into account in-house resources, EHR vendor involvement, and costs). The health system's project manager sought input from IT staff, providers, corporate leaders, and the EHR vendor. Even after prioritizing the requirements based on this information, in a children's hospital owned by a national corporation, changing an EHR is "a slow process and a long-term political campaign," said the project manager.

The health systems that had to be more selective about incorporating Format requirements into their EHRs because of resource constraints said that the well-child visit and immunization categories were their highest priorities, followed by the patient portal (which overlaps with the CMS Medicaid EHR Incentive Program), children with special health care needs, and the confidentiality of information about minors. One health system said that it used the "shall" requirements to set priorities. No systems said that they disagreed with the "shall" requirements, but, for whatever reason, most did not explicitly use the Format's implied prioritization in decisions about EHR modification.

Focusing on EHR reporting and training. Given practices' limited IT resources and leverage with vendors, the North Carolina CHIPRA quality demonstration team has itself taken steps to align the Format with practices' ability to use their EHRs to capture and report care processes for quality improvement. As of spring 2014, the team had developed quality measures written specifically for EHRs to guide vendors when, in the State's opinion, Format requirements provided insufficient direction. A few vendors had begun producing EHR reporting tools as the State envisioned. At the same time, the practices and the EHR coaches were still involved in the comparison process, and the coaches were trying to arrange for EHR vendors to train them in selected functionalities so that they could train practice staff.

Struggling to involve vendors. As in earlier stages of the project, practices and health systems had difficulty engaging their EHR vendors when vendor assistance was needed to modify EHRs or to train coaches in EHR functionalities. Based on these experiences, CHIPRA quality demonstration staff, project managers, and EHR users concluded that most vendors do not see a compelling business reason to make their products Format-compliant or to meet needs for children's health IT more generally. Instead, these stakeholders believe the vendors' top priorities are the ICD-10 transition (mandatory changes in reporting medical diagnoses and inpatient procedures) and achieving certification under the CMS Medicaid EHR Incentive Program (which greatly affects EHR marketability).

Conclusion

As a result of the two States' efforts during the CHIPRA quality demonstration, the Format has been tested by independent primary care practices, large children's hospitals and their ambulatory practice sites, an FQHC, and a small rural hospital. The Format has been compared with 10 EHRs.

State and provider stakeholders generally found the Format they received to be a major advance in the specification of child-oriented EHR functions. The overall appreciation for the Format's thoroughness was diminished by the time-consuming process of comparing the Format to existing EHRs. As they prioritized the Format requirements and staff training needs, the health systems and practices confronted the limits of their health IT resources, their leverage with EHR vendors, and the availability of providers to participate in the comparison process.

Lack of vendor participation impeded progress in both States. For example, North Carolina found that vendors needed clinical and informatics guidance to incorporate the Format requirements in a way that supports the State's desired improvement in children's health care. However, when EHR coaches and health systems had the attention of vendors, their testing of the Format helped them to identify and discuss their expectations for a child-oriented EHR.

Implications

The findings from North Carolina and Pennsylvania have implications for States and other stakeholders interested in using EHRs as a tool for measuring and improving children's health care quality. The experiences and feedback from North Carolina and Pennsylvania could also be useful to CMS and AHRQ as they continue to refine the Format, prioritize requirements, and improve the Format's usability.

- States should consider broadly disseminating current and future versions of the Format to providers that serve children in order to stimulate discussion about and move toward more robust, child-oriented EHRs. Because many providers cannot devote attention to 700 requirements, States could consider disseminating only the following: (1) the requirements that best align with their current quality improvement priorities, (2) the Format's prioritized "shall" requirements, or (3) the subset of critical/core requirements now available through AHRQ's United States Health Information Knowledgebase (these had not been specified when the Format was initially released to North Carolina and Pennsylvania).

- The Format can help EHR purchasers and frontline users prioritize their needs and develop strategies to encourage vendors to meet those needs. Independent practices and health systems that use the same EHR product could consider approaching EHR vendors together to increase their negotiating strength.

- The Federal government could motivate EHR vendors to create products that meet the requirements of the Format by developing an EHR certification module for child health that, in turn, could create a market for certified child-oriented EHRs. Depending on AHRQ's and CMS's enhancements to the Format, it may be desirable to develop more than one module, including one for a core or minimum set of requirements.

- EHR vendors could consider demonstrating the extent to which their products already meet Format requirements and helping providers use their products accordingly. Vendor-sponsored user-group meetings would be a suitable venue for efficiently reaching large numbers of providers who serve children.

AcknowledgmentsThe national evaluation of the CHIPRA Quality Demonstration Grant Program and the Evaluation Highlights are supported by a contract (HHSA29020090002191) from AHRQ to Mathematica Policy Research and its partners, the Urban Institute and AcademyHealth. Special thanks are due to Cindy Brach, Linda Bergofsky, and Erin Grace at AHRQ; Karen LLanos and Elizabeth Hill at CMS; State CHIPRA quality demonstration staff; and Mathematica colleagues Mynti Hossain, Dana Petersen, Joe Zickafoose, and Henry Ireys. We particularly appreciate the time that the CHIPRA quality demonstration staff and providers in the featured States spent answering our questions during site visits. The observations in this document represent the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or perspectives of any State or Federal agency. |

| Learn More Additional information about the national evaluation and the CHIPRA quality demonstration is available at http://www.ahrq.gov/policymakers/chipra/demoeval/. Use the tabs and information boxes on the Web page to:

|

Endnotes

1 Andrew SS. We are still waiting for fully supportive electronic health records in pediatrics. Pediatrics 2012;130(6):e1674-6.

2 Andrew SS. Special requirements of electronic health records in pediatrics. Pediatrics 2007;119(3):631-7.

3 The pay-for-improvement project that Pennsylvania established as part of its CHIPRA quality demonstration was separate from, and not redundant with, the Medicaid Meaningful Use Incentive Program established by the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act of 2009.