How are CHIPRA quality demonstration States using quality reports to drive health care improvements for children?

Evaluation Highlight No. 11

Authors: Grace Anglin and Mynti Hossain

Contents

| The CHIPRA Quality Demonstration Grant Program In February 2010, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) awarded 10 grants, funding 18 States, to improve the quality of health care for children enrolled in Medicaid and the Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP). Funded by the Children's Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2009 (CHIPRA), the Quality Demonstration Grant Program aims to identify effective, replicable strategies for enhancing quality of health care for children. With funding from CMS, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) is leading the national evaluation of these demonstrations. The 18 demonstration States are implementing 52 projects in five general categories:

|

This Evaluation Highlight is the 11th in a series that presents descriptive and analytic findings from the national evaluation of the Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2009 (CHIPRA) Quality Demonstration Grant Program.1 The Highlight focuses on how six States are using quality reports to draw attention to State- or practice-level performance on quality measures in order to drive improvements in the quality of care for children.

Key Messages

- States indicated that implementing a range of State- and practice-level initiatives is often needed to improve outcomes on a specific measure.

- States formed workgroups or held formal discussions to review quality reports with stakeholders, including staff at child-serving agencies, health plans, and health systems. These discussions helped spur interest in quality improvement (QI) and sharpen the focus on child health.

- Practices found reports helpful for identifying QI priorities but less useful for guiding and assessing QI projects.

- Practices needed technical assistance from the State to understand the quality reports and to develop QI efforts to improve performance.

Background

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) encourages all States to voluntarily report on the Core Set of Children’s Health Care Quality Measures for Medicaid and CHIP (Child Core Set) each year.2 The measures cover a range of physical and mental health domains, including preventive care and health promotion, the management of acute and chronic conditions, the availability of care, and the ways in which families experience care.

Ten of the 18 States participating in the CHIPRA quality demonstration used a portion of their grant funding to report on the Child Core Set to CMS.3 Six of these States—Alaska, Florida, Illinois, Maine, Massachusetts, and North Carolina—also used quality reports to drive statewide QI efforts (Figure 1). All six of these States used existing data (for example, Medicaid claims data and immunization registries) to generate reports for State-level stakeholders, such as the staff at child-serving agencies and health plans. Maine, Massachusetts, and North Carolina also used these data to develop reports on quality for practices in the State that serve children in Medicaid and CHIP. This Highlight describes the reports States produced, how States used the reports to encourage QI at the State and practice levels, and the changes that occurred as a result.

The information in this Highlight comes from semi-structured interviews conducted by the national evaluation team in spring 2012 and spring 2014 with staff at State agencies, health plans, consumer groups, professional associations, and primary care practices. The Highlight also draws on the semi-annual progress reports that States submitted to CMS in 2012, 2013, and 2014.

Two previous Evaluation Highlights in this series covered grantees’ quality measurement work. The first Highlight described the technical and administrative steps States took to calculate quality measures at the practice level. The fifth Highlight outlined how practices and health systems used data from electronic health records (EHRs) and manual chart reviews to track their own quality performance.

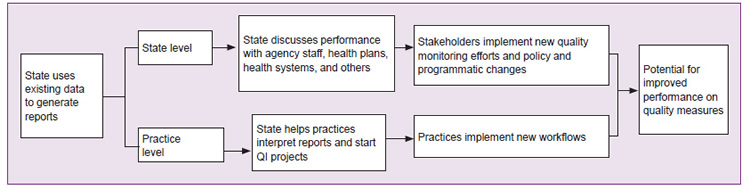

Figure 1. How States Used Quality Reports to Drive QI at the State and Practice Levels

Note: All six States pursued State-level reporting and quality improvement activities. Maine, North Carolina, and Massachusetts produced practice-level reports from existing State-level data sources; only North Carolina and Maine helped practices use those reports for QI.

Findings

Quality reports helped spur State-level QI activities

Assessing statewide performance. All six States used statewide reports to (1) compare performance on quality measures for children in Medicaid and CHIP to national benchmarks, (2) identify variation in practices’ performance across regions or plans, and (3) track changes in performance over time.4 In addition, Massachusetts used data that health plans submitted to the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) and its own all-payer claims database to include commercially insured children in its reports. According to CHIPRA quality demonstration staff, the State now has a more complete picture of performance.

Engaging stakeholders to identify QI priorities. States indicated that developing strategies to address poor performance requires a collective effort among stakeholders, including staff at child-serving agencies, professional associations, health systems, health plans, and consumer advocacy groups. To that end, CHIPRA quality demonstration staff formed workgroups charged with using data on the quality of care to identify QI priorities, reached out directly to agency leaders to discuss quality reports, or both.

Maine developed a workgroup that meets every 6 months and includes representatives from child-serving practices, child advocacy organizations, professional associations, public and private payers, and the public health system. In Alaska, CHIPRA quality demonstration staff review annual reports on Medicaid and CHIP performance directly with leaders in Medicaid, health information technology, and public health agencies.

Workgroups and agency leadership considered a variety of factors to determine which measures should be the focus of QI activities, including whether the measure aligned with existing initiatives and priorities, room for improvement, data quality, and the cost and burden of tracking performance.

|

This [statewide report] was the first attempt by our department to be this transparent with . . . how children in the Medicaid program are faring. We think it was a landmark document because it will [allow us to] compare the various Medicaid Managed Care plans. —Illinois Medicaid Staff, June 2014 |

Several States indicated that selecting priority areas was difficult and slow when groups new to QI were actively engaged or when a large number of groups were involved in the decisionmaking process. To facilitate the conversation, States included information in State-level reports that coincided with their priorities and context. For example, Florida and Illinois are reporting measures for their State as a whole and for each Medicaid managed care plan. In addition, both of these States and Maine developed short fact sheets on potential QI areas that highlight the States’ quality measure performance and describe potential strategies for improving performance.

Pursuing new QI activities. The States’ stakeholder-engagement activities helped to stimulate interest in QI generally and sharpened the focus on child health quality in particular.

|

“Measure reports [have] been useful for disseminating information about what’s going on and what needs to be worked on. [Performance on] all of the measures hasn’t been great, so bringing awareness to those areas has been a great opportunity for the State.” —Florida Demonstration Staff, May 2014 |

As shown in Table 1, the CHIPRA quality demonstration staff and stakeholders reported that the States implemented two types of changes:

- Established new quality monitoring activities or realigned existing activities, not only to create a more powerful incentive for providers to improve care, but also to make it easier for the State to compare programs’ performance.

- Implemented policy or programmatic changes intended to improve performance on quality measures.

Table 1. State-Level Activities Spurred in Part by the CHIPRA Quality Demonstration

| Improved Monitoring of Child Health Quality Measures | |

|---|---|

| Alaska |

|

| Florida |

|

| Illinois |

|

| Maine |

|

| Massachusetts |

|

| Policy and Programmatic Changes | |

| Alaska |

|

| Florida |

|

| Maine |

|

| North Carolina |

|

Source: Interviews with staff at State agencies, health plans, and consumer groups.

a The Alaska Medicaid Coordinated Care Initiative is a case management and utilization review program.

b Accountable care entities are integrated delivery systems similar to managed care organizations.

c Under the Accountable Communities Initiative, Maine Medicaid offers providers who coordinate care for a designated population the opportunity to share in savings.

d The Health Homes Initiative provides enhanced reimbursement to providers who manage patients with complex chronic conditions.

e Pathways to Excellence publicly reports quality data on hospitals and primary care practices.

|

“We have gotten a lot of buy-in around the State on quality measurement…and all of this work is starting to pay off. We have programs that are adopting our measures or using them for pay for performance. That has been our goal and we’ve been able to achieve it.” —Maine Demonstration Staff, July 2014 |

Practices needed help to interpret quality reports and launch data-driven QI initiatives

States supplemented enhanced reports with technical assistance. Two States, Maine and North Carolina, also used CHIPRA quality demonstration funds to make quarterly reports comparing practices to their peers more useful to practices. For example, both States developed systems that allow practices to pull reports directly from State systems, increasing real-time access to information. Practices indicated that the reports helped them assess their performance and identify QI priorities.

Despite enhancements to the State-generated reports, practices found it challenging to interpret quality reports and use them to track performance. For example, long delays in claims processing and infrequent reporting periods made it difficult for practices to use reports to assess redesigned workflows. Practices in Maine and North Carolina also became overwhelmed when presented with long quality reports.

Anticipating that practices would need assistance, North Carolina used practice facilitators, and Maine used a learning collaborative approach to help practices improve quality performance (see text box). Both States helped practices run reports from their EHRs or conduct chart reviews so they could get more real-time information between reporting periods. (The two States cautioned that, while useful, EHR-derived measures may not be comparable to State benchmarks and chart reviews cover a small number of patients.)

|

State Technical Assistance for Practices North Carolina embedded a practice facilitator in each of 14 regional primary care networks. The practice facilitators reviewed the quality reports for more than 200 practices and helped them identify priority areas for QI activities, develop a QI team, and implement workflow changes. Practice facilitators also trained 120 providers to apply fluoride varnish (identified as a priority through State-level quality reports). Maine used State-level quality reports to identify topics for a series of four 9-month-long learning collaboratives for practices. The State then used practice-level reports to generate the practices’ interest in the topics and to help practices identify areas for improvement, such as the age ranges for which the practice needs to increase immunization rates. The collaboratives involved 12 to 31 practices. |

The two States also encouraged practices to focus on a subset of measures at a time. Practice facilitators in North Carolina, for example, suggested that practices work on the one or two measures with the greatest room for improvement, rather than going over all measures in the practice reports. Similarly, Maine elected to focus on one or two QI topics in each of its learning collaboratives.

|

“Getting feedback from someone outside [of the practice] is really the only way you can improve . . . When it comes to ourselves, we have tunnel vision.” —North Carolina Practice Manager, March 2014 |

Practices implemented workflow changes. Practices reported that concrete changes came about as a result of their work with practice facilitators or their participation in the learning collaboratives. For instance, one North Carolina practice implemented behavioral and risk-factor screening for school-age children and adolescents. Another started running reports from its EHR system to identify patients due for immunizations and autism screenings.

Maine CHIPRA quality demonstration staff indicated that, after participating in a learning collaborative on developmental screening, 12 practices began to follow evidence-based guidelines for developmental screening for almost all children seen in their practice at age 1 and for a majority of children at ages 2 and 3. These 12 practices serve approximately 14 percent of children enrolled in Medicaid and CHIP in the State. Furthermore, practices in Maine used various strategies for improving their screening rates, including developing pre-visit summaries and reminder systems indicating if a child is due for screenings and improving coordination with early intervention programs.

Statewide improvement on quality measures required a mix of strategies

Maine and North Carolina reported improvement on several measures for all children enrolled in Medicaid and CHIP (Table 2). Maine reported increases in the percentage of children in Medicaid and CHIP who received standardized screenings for developmental, behavioral, and social delays from a rate close to zero to a small but meaningful proportion of children. Similarly, North Carolina made modest but meaningful improvements in most of the areas it focused on for the CHIPRA quality demonstration. It is likely that these improvements represent both an increase in the provision of needed services as well as more accurate billing for services that practices were already providing.

Both States attributed statewide improvement on measures to an array of practice- and State-level initiatives, including their work with individual practices, QI initiatives spurred by stakeholder engagement efforts started by CHIPRA quality demonstration staff, and other initiatives in the two States.

Table 2. State Reported Changes in Measures for All Children Enrolled in Medicaid and CHIP

| 2010 | 2011 | 2013 | Change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mainea | ||||

| Standardized screenings for developmental, behavioral, and social delays for children | ||||

| Birth to 1 year | - | 2% | 13% | ↑11% |

| 1 to 2 years | - | 3% | 17% | ↑14% |

| 2 to 3 years | - | 1% | 12% | ↑11% |

| North Carolina | ||||

| Dental varnishing rates for childrenb | ||||

| 3 years and older | 52% | 55% | 58% | ↑6% |

| 4 years and older | 37% | 40% | 43% | ↑6% |

| Standardized behavioral and risk-factor screening | ||||

| School-age children | - | 6% | 10% | ↑4% |

| Adolescents | - | 7% | 12% | ↑5% |

| M-CHAT autism screeningc | - | 42% | 55% | ↑13% |

| Body mass index assessments | - | 3% | 13% | ↑10% |

| Standardized developmental screening | - | 74% | 69% | ↓5% |

Note: Data reported by Maine and North Carolina CHIPRA quality demonstration staff and not independently validated.5, 6

a The measures reported by Maine are part of the Child Core Set.

b North Carolina provided 2010 data for only the dental varnishing measures.

c Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT) is a standardized screening tool for autism spectrum disorders.

In contrast, developmental screening rates in North Carolina decreased over the course of the CHIPRA quality demonstration. The State believes that the apparent decrease may be an artifact of a shift to EHR systems that bill for screenings as part of a larger bundle of preventive services (as opposed to billing for the screener alone).

States plan to sustain quality reporting and QI efforts

The States are planning to sustain some of their QI activities or to spread them throughout the State after the CHIPRA quality demonstration ends. For example, North Carolina and Maine plan to continue generating quality reports showing performance at both the State and practice levels. In addition, several regional primary care networks in North Carolina will continue employing practice facilitators and plan to implement QI strategies for adults that are similar to their strategies for children. Several States also indicated that the program and policy changes that came about partly because of the CHIPRA quality demonstration will help them to stay focused on the quality of care for children after their funding ends. Examples of these changes are Illinois’s inclusion of Child Core Set measures in its contracts with accountable care entities and managed care organizations, and Alaska’s creation of a quality workgroup.

Conclusion

The six States’ experience with using reports to drive improvements in the quality of care for children confirms previous findings that change requires more than simply producing and disseminating reports on quality measures.7 CHIPRA quality demonstration staff had to actively engage stakeholders at the State and practice levels to foster change. For example, the States used reports on all children in Medicaid and CHIP to educate agency staff, health plans, and other stakeholders about the gaps in quality of care for children. The conversations that grew out of these efforts gave rise to new quality monitoring initiatives and policy changes. At the practice level, reports were a useful tool for prioritizing QI efforts, but they were less helpful for assessing QI efforts because of delays in claims processing and infrequent reporting periods. Moreover, to achieve concrete changes, most practices needed technical assistance from the State to establish a QI process, implement new workflows, and use data from EHRs or paper charts to track their performance over time.

Implications

The findings in this Highlight suggest that States interested in using quality reports to drive improvements in health care for children may want to consider:

- Incorporating feedback from end users to make reports more actionable.

- Selecting a few high-priority quality measures to focus on and then using multiple approaches—statewide quality workgroups and practice-level technical assistance, for example—to improve practices’ performance on these measures.

- Forming State or regional workgroups charged with discussing quality reports with stakeholders, identifying areas for improvement, and designing QI initiatives.

- Providing practices with technical assistance to help them interpret practice-level quality reports, identify QI priority areas, and implement QI activities.

- Encouraging practices to generate their own quality reports by using EHR data or chart audits of a sample of records so that they can assess the impact of workflow changes in a timely fashion.

AcknowledgmentsThe national evaluation of the CHIPRA Quality Demonstration Grant Program and the Evaluation Highlights are supported by a contract (HHSA29020090002191) from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) to Mathematica Policy Research and its partners, the Urban Institute and AcademyHealth. Special thanks are due to Cindy Brach and Linda Bergofsky at AHRQ, Barbara Dailey and Elizabeth Hill at CMS, and our colleagues for their careful review and many helpful comments. We particularly appreciate the help received from CHIPRA quality demonstration staff, providers, and other stakeholders in the six States featured in this Highlight and the time they spent answering many questions during our site visits and telephone calls and reviewing an early draft. The observations in this document represent the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or perspectives of any State or Federal agency. |

Learn moreAdditional information about the national evaluation and the CHIPRA quality demonstration is available at http://www.ahrq.gov/policymakers/chipra/demoeval/. Calculating quality measures

Developing quality reports

Encouraging State-level QI

Encouraging practice-level measurement and QI

Use the tabs and information boxes on the Web page to also:

|

Endnotes

1 We use the term “national evaluation” to distinguish our work from the activities of evaluators who, under contract to many of the grantees, are assessing the implementation and outcomes of State-level projects. The word “national” should not be interpreted to mean that our findings are representative of the United States as a whole.

2 For more information on the CHIPRA Child Core Set, visit https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/quality-of-care/performance-measurement/adult-and-child-health-care-quality-measures/childrens-health-care-quality-measures/index.html.

3 The following States used a portion of their CHIPRA quality demonstration funding to report on the Child Core Set to CMS: Alaska, Florida, Illinois, Maine, Massachusetts, North Carolina, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, and West Virginia.

4 States compared their performance to that of other States that are reporting the Child Core Set to CMS and to national benchmarks on both the NCQA Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) and the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) measures.

5 CHIPRA quality demonstration semiannual progress report. Prepared by Maine and Vermont, August 2014.

6 CHIPRA quality demonstration semiannual progress report. Prepared by North Carolina, August 2014.

7 Ivers NM, Grimshaw JM, Jamtvedt G, et al. Growing literature, stagnant science? Systematic review, meta-regression and cumulative analysis of audit and feedback interventions in health care. J Gen Intern Med 2014; 29(11):1534-41. PMID: 24965281