Spotlight on New Mexico

July 2015

This brief highlights the major strategies, lessons learned, and outcomes from New Mexico's experience in the quality demonstration funded by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) through the Children's Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2009 (CHIPRA). For this 5-year demonstration, CMS awarded 10 grants that supported efforts in 18 States to identify effective, replicable strategies for enhancing the quality of health care for children. With funding from CMS, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality is leading the evaluation of the program.

New Mexico’s Goals: Work with school-based health centers to improve care for adolescents by—

Partner State: New Mexico partnered with Colorado to design and implement demonstration strategies across both States |

New Mexico helped SBHCs to monitor quality and implement QI projects

New Mexico hired quality improvement (QI) coaches to help participating school-based health centers (SBHCs) carry out QI projects. First, QI coaches worked with SBHCs to improve the delivery and documentation of preventive services recommended by the Early and Periodic Screening Diagnosis and Treatment (EPSDT) standards for well child visits.1 The coaches and SBHCs then addressed other QI topics given high priority by the State—pediatric overweight and obesity, depression and anxiety, sexual health, and immunizations. While working with the first of three cohorts of SBHCs, demonstration staff realized that supporting centers, many of which had limited experience with QI, took more time and resources than anticipated. As a result, New Mexico focused the work of QI coaches on 11 SBHCs instead of 17, as originally planned. Each SBHC received between $10,000 and $13,000 in grant funds for each year it participated in the demonstration. With this support, SBHCs—

- Used quality reports to guide QI efforts. CHIPRA demonstration staff used quality data submitted by each SBHC into an existing repository to support the generation of quality reports for each center. These quality reports were used to guide QI activities.

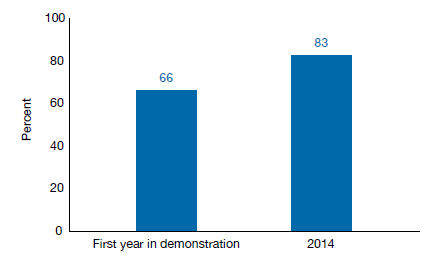

- Pursued QI projects. All participating SBHCs sought to increase provision and thorough documentation of EPSDT preventive services, and they made good progress toward this goal (Figure 1). To improve performance in other priority areas as well, one SBHC scheduled regular followup appointments for youth that are overweight; another developed electronic health record (EHR) templates to help guide and document screening for sexually transmitted infections. SBHCs made these improvements while grappling with staff turnover and competing priorities for staff time.

Figure 1. Increase in the percentage of adolescents seen in participating Colorado SBHCs with all EPSDT- recommended services documented

Note: Data were reported by New Mexico and not independently validated. The State analyzed 10 medical records for each of the 11 SBHCs participating in New Mexico in the fall of their first year in the demonstration (2011, 2012, or 2013 depending on the cohort) and in 2014.

New Mexico supported the implementation of an electronic risk assessment

To get a fuller picture of the health risks facing adolescents, demonstration staff in New Mexico and Colorado—

- Developed an electronic questionnaire that screens adolescents for social and behavioral risk factors, including poor nutrition, an unsafe home environment, unsafe sexual practices, substance abuse, and depressed or anxious mood. The States drew on existing tools and guidelines to develop the questionnaire and worked with information technology experts to format it for a tablet. Adolescents completed the screener at the health center while waiting to see a provider for the first time each school year. The system supporting the screener automatically flags risk factors and uploads the results to the providers’ tablets so they can discuss health risks with adolescents during their visit.

- Implemented the questionnaire in 21 SBHCs in New Mexico. New Mexico piloted the screener in the 11 SBHCs working with QI coaches. Two-thirds of the middle school students (64 percent) and half of the high school students (50 percent) who visited these SBHCs during the 2013–2014 school year completed the screener. SBHCs reported that the students felt more comfortable with the electronic screener than with paper-based screeners because they liked using the tablet. However, the State and the SBHCs indicated that the neeed to continually train staff in how to use the tool and incompatibility between the screener and EHR systems made implementation challenging. To address the latter, New Mexico made changes to the EHR system used by most SBHCs. After improving interoperability issues, the State used other sources of funding to implement the screener in 10 other SBHCs.

- Helped SBHCs improve patient care and population management. SBHC staff indicated that the electronic screener helped them identify adolescents who needed additional counseling or service. When aggregated, the screening data also helped centers to identify new services they should offer to address common concerns. For example, most SBHCs started using standardized behavioral health screeners to determine whether youth identified as at a risk for depression or anxiety should be referred to a mental health provider.

New Mexico encouraged SBHCs to engage youth in their own care

The State aimed to increase youth engagement to improve their ability to access and use community health resources effectively. In conjunction with Colorado, New Mexico—

- Developed and fielded the Youth Engagement with Health Services (YEHS!) survey.2 The States worked with youth engagement experts, QI coaches, and students to develop the survey, which assessed youth health literacy as well as their perceptions of access and quality. SBHC staff administered more than 1,000 surveys to youth in New Mexico. Some SBHCs used the aggregated results to tailor staff training. For example, a center trained staff to serve lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth in a culturally sensitive manner.

- Helped SBHCs implement new youth engagement strategies. Most SBHCs had limited experience in implementing youth engagement strategies, and some were unsure about how to engage youth in a useful way. To get them started, QI coaches in New Mexico distributed short reports highlighting YEHS! survey results and educated SBHCs about youth engagement strategies when they visited the centers. The State also developed youth engagement and health education resources that centers shared directly with youth. Some SBHCs also formed youth advisory groups to get first-hand input on how to improve their services.

SBHCs implemented features of the medical home model

New Mexico sought to enhance the medical home features of participating SBHCs.3 With help from QI coaches, SBHCs—

- Assessed where they fell along the medical home spectrum. New Mexico developed a short tool based on the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) patient-centered medical home model, which SBHCs used to guide their medical home improvement.4 The State modified the existing NCQA tool because it was too burdensome for many SBHCs, especially since no State financial incentives were tied to NCQA recognition.

- Expanded their medical home features. In addition to the efforts described above, SBHCs pursued several other QI activities. These included referring youth to the State's 24/7 nurse help line to improve access after SBHC hours and establishing formal referral relationships with community providers. In many cases, SBHCs affiliated with federally qualified health centers and that had EHRs more easily implemented new processes than did their counterparts.

Key demonstration takeaways

- SBHCs leveraged the substantial technical and financial assistance provided by the State to obtain and use data and develop new processes for monitoring and improving quality, and for engaging youth. Competing priorities for staff time, continued need for staff training, and system incompatibility made implementing these projects challenging in some locations.

- Electronic screeners administered on tablets were well received by youth. The screeners produced important information on youth’s social and behavioral health-related risk factors that helped New Mexico SBHCs discuss sensitive topics with youth and improve population health management.

- Participating SBHCs are interested in maintaining the momentum from the demonstration but are concerned about securing needed resources to implement new QI projects and continue the use of the electronic screeners.

| Continuing Efforts in New Mexico

Following the CHIPRA quality demonstration —

|

Endnotes

- For more information on the EPSDT benefit, visit www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Benefits/Early-and-Periodic-Screening-Diagnostic-and-Treatment.html.

- Sebastian RA, Ramos MM, Stumbo S, et al. Measuring youth health engagement: development of the Youth Engagement with Health Services Survey. J Adolesc Health 2014;55(3):334-340.

- The patient-centered medical home model is a primary care model designed to improve the quality of and access to care, and to engage youth and their families in their own care.

- For more information on the NCQA medical home model, visit http://www.ncqa.org/Programs/Recognition/Practices/PatientCenteredMedicalHomePCHM.aspx

Learn More

New Mexico’s CHIPRA quality demonstration experiences are described in more detail on the national evaluation Web site available at http://www.ahrq.gov/policymakers/chipra/demoeval/demostates/nm.html.

The following products highlight New Mexico’s experiences—

- Evaluation Highlight No. 3: How are CHIPRA quality demonstration States working to improve adolescent health care?

- Evaluation Highlight No. 6: How are CHIPRA quality demonstration States working together to improve the quality of health care for children?

- Evaluation Highlight No. 8: CHIPRA quality demonstration States help school-based health centers strengthen their medical home features.

- Reports from New Mexico: New Mexico completed an analysis of encounter data for SBHCs. The Youth Engagement and Health Services Surveys are publicly available.

| The information in this brief draws on interviews conducted with staff in New Mexico and Colorado agencies and participating SBHCs and a review of project reports submitted by New Mexico and Colorado to CMS.

The following staff from Mathematica Policy Research and the Urban Institute contributed to data collection or the development of this summary: Grace Anglin, Ian Hill, Ashley Palmer, Margo Wilkinson, and Arnav Shah. |