Making Healthcare Safer III: Executive Summary

ES. 1 Background/Introduction

The Making Health Care Safer reports from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) have had an important role in reducing harm and improving the safety and quality of care for patients. The reports—providing an analysis of the evidence for various patient safety practices (PSPs)—have served as a source of information for multiple stakeholders, including healthcare providers, health system administrators, researchers, and government agencies. The reports have also identified contextual factors that contribute to successful PSP implementation. The reports have helped to shape national discussion regarding patient safety issues on which providers, payers, policymakers, and patients and families should focus attention.1,2

Since the second report was published in 2013, there have been many improvements in patient safety. Building on the success of PSPs in inpatient settings, AHRQ is seeking to support a culture of safety across the healthcare continuum, including in nursing homes, home care, outpatient, and ambulatory settings, and during care transitions. Making Healthcare Safer III has made strides in transitioning from a predominantly acute care PSP review to include PSPs from other settings and during transitions. The scope of this report has also expanded to match emerging themes and strategic goals championed by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, including addressing the opioid crisis and emerging health risks (e.g., multidrug-resistant organisms), and overall directives to “put patients first” and to reduce provider burden and burnout.

The Making Healthcare Safer III report project team, composed of Abt Associates and IMPAQ International, began its work by developing a new conceptual framework that does the following: (1) puts the patient in the center; (2) acknowledges that patients are constantly exposed to potential harms; and (3) proposes patient safety approaches that mitigate patients’ past and future vulnerabilities. We have thus taken an approach that is both holistic (considering the whole patient through the continuum of care) and targeted (focusing on what harms are relevant to a particular patient at a particular point in care). Additionally, by following the patient, this framework includes harms during movement between settings and harm risks from existing vulnerabilities and disparities. Starting from the new conceptual framework, we organized the report by “harm areas.” This is intended to make the report easier to access for all patient safety stakeholders, who will be able to quickly locate topics of interest and importance to their particular needs and circumstances.

ES. 2 Objectives

The purpose of the Making Healthcare Safer III report is to create a source of information on practices that can improve patient safety across a variety of settings and stakeholders. For this report, patient safety practices are defined as “discrete and clearly recognizable structures or processes used for the provision of care that are intended to reduce the likelihood and/or severity of harm due to systems, processes, or environments of care.”3 A PSP may have varying degrees of evidence to support its ability to prevent or mitigate harm or its use in specific contexts.

ES.3 Methods

The methods by which the full project team—including AHRQ and the patient safety and clinical experts on the Advisory Group (AG) and Technical Expert Panel (TEP)—completed the report are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1: Six-Step Process to Developing the Making Health Care Safer III Report

| Steps | |

|---|---|

| 1. | Development of Conceptual Framework |

| 2. | Identification, Selection, and Prioritization of Harm Area Topics |

| 3. | Identification, Selection, and Prioritization of Patient Safety Practices |

| 4. | Literature Searches |

| 5. | Review of the Evidence |

| 6. | Report Development |

ES.3.1 Step 1. Development of Conceptual Framework

ES.3.1.1 Description of Framework

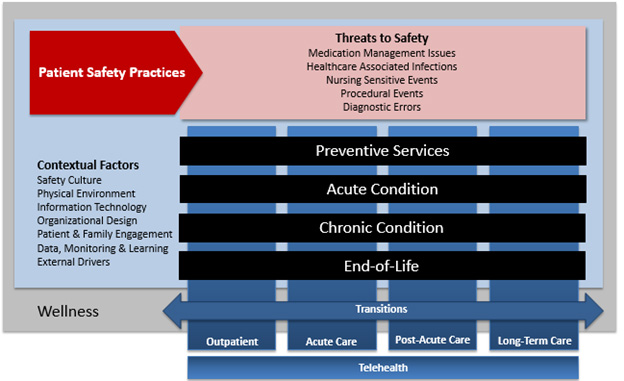

To help guide the development and content of this report, the project team created a patient-centric framework of safety. The framework focuses on the experience of the individual as they interact with the health care system throughout various phases of health and in different settings (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Framework for Making Healthcare Safer III Report

The underlying state of the individual is wellness, in which the patient may be receiving intermittent preventive care, such as surveillance for diseases or immunizations, or receiving regular care to maintain stability of chronic conditions. As the patient moves from state to state, they interact with different providers in different settings and the resources, tools, culture, and environments specific to those settings. Threats to safety including medication management issues, healthcare-associated infections, nursing-sensitive events, procedural events, and diagnostic errors can be present during these interactions and patient safety practices (PSP), which are the focus of this report, are used during the provision of care to mitigate the effects of these threats.

ES.3.2 Step 2. Identification, Selection, and Prioritization of Harm Area Topics

The project team conducted an environmental scan of patient safety resources to identify existing and potentially new harm areas. Sources reviewed included AHRQ’s PSNet website, the National Quality Strategy, the Joint Commission’s National Patient Safety Goals, the National Quality Forum’s 2015 Patient Safety Report, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Hospital Value-Based Purchasing Program and Partnership for Patients, ECRI Institute’s 2017 and 2016 Top 10 Patient Safety Issues briefs, and Becker’s Hospital Review 10 Top Patient Safety Issues for 2018.4-12 This scan identified 8 broad categories of harm (e.g., healthcare-associated infections) and 74 specific harm area topics (e.g., Clostridium difficile infection).

The AG performed an initial review of the identified harm areas and topics, resulting in the exclusion of seven topics deemed outside the scope of this report. In order to determine which of the remaining 67 topics should be included, the TEP and AG prioritized the topics on a scale of 1 to 5 (1 = low priority; 5 = high priority) and provided feedback through an electronic survey. The results were presented to AHRQ and, after several iterative rounds, which included adding several topics not among the initial 67 harm area topics (shown in Table 2 of the report's Methods section), a total of 17 harm area topics (shown in Table 3 of the report’s Methods section) were identified for inclusion in the report.

ES.3.3 Step 3. Identification, Selection, and Prioritization of Patient Safety Practices

The project used guidelines and systematic reviews to identify PSPs for the 17 harm area topics. The inclusion of a PSP in the report was based on how many TEP and AG members selected a specific PSP as a high priority for inclusion. After a comprehensive review of the results by AHRQ, a master list of 47 PSPs composed of 40 core PSPs and 7 additional AHRQ-identified PSPs was generated.

ES.3.4 Step 4. Literature Searches

The authors identified PSP-specific search terms and the team librarian ran the search terms for every PSP in the MEDLINE and CINHAL databases while also filtering for English-language publications only between the years 2008 and 2018. The individual studies for some PSPs, such as Patient and Family Engagement and Cultural Competency, were limited; therefore, the project team followed the approach outlined by Whitlock et al. (2008), which was to search for systematic reviews first and decide if the primary literature was of a determined level of adequate quality.13 The MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) was then applied to determine systematic review quality.14 The studies were screened based on the exclusion criteria established using the population, interventions, comparators, outcomes, and study designs (PICOS) criteria.15 For example, we excluded studies with specialized populations such as armed forces and pilot study designs, particularly when the PSP was considered new or developing. Other exclusion criteria included lack of rigor, small sample size), lack of intervention or protocol description, PSP not universally applicable to most settings and populations, and study found to be out of scope.

ES.3.5 Step 5. Review of the Evidence

Across the PSPs examined there was wide variation in the rigor of studies included in the evidence reviews, and individual authors were permitted to decide the minimum threshold of quality for including specific studies given the state of the field for each PSP. Similar to the previous report (Making Health Care Safer II), we aimed to apply the criteria drawn from the AHRQ Guides on strength of evidence derived from Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations (GRADE), a framework for developing and presenting summaries of evidence.2,16-19 To the extent possible, authors for each review indicated the strength of evidence by practice, outcome, and/or setting.

ES.3.6 Step 6. Report Development

For this report, the project team has made an effort to synthesize the evidence through a research lens, while placing it in a format that allows for practical application for the end user. Each chapter, as written by the project team with final review from AHRQ, represents a specific threat to safety (i.e., the harm) that can occur to a patient when exposed to healthcare and includes the targeted PSPs selected for review.

Given the wide variation in study availability and quality, as well as the variation in strength of evidence sometimes by setting and specific outcomes, the project team decided against providing a single determination of strength of evidence by PSP (as was done in the previous report). Instead, the project team—with expert input from AHRQ, the TEP, and the AG—determined it was most appropriate to provide tables that summarize for each harm area, by PSP, the following: key safety outcomes: Table 2 summarizes these points for each PSP to provide a user-friendly overview of what stakeholders will find in each specific review.

ES.4 Results

The results of the 47 PSPs grouped according to the 17 topics are summarized in Table 2. Instead of including strength of evidence for each PSP, the project team decided to include key takeaways as a way to allow the user to determine if the PSP is of interest or beneficial.

Table 2: Patient Safety Practice Summary Table

| Patient Safety Practice | Key Safety Outcomes | Studies and Systematic Reviews (#) | Settings | Key Takeaways/Points |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic Error: Clinical Decision Support (CDS) |

|

31 studies; 3 systematic reviews; 1 meta-review; 1 meta-analysis |

Inpatient and outpatient (primary care and specialty care), emergency department (ED) |

|

| Diagnostic Error: Peer Review |

|

14 studies; 2 systematic reviews |

Inpatient and outpatient (radiology and pathology) |

|

| Diagnostic Error: Result Notification Systems (RNS) |

|

15 studies; 2 systematic reviews |

Inpatient and outpatient (primary care and specialty care), ED |

|

| Diagnostic Error: Education and Training |

|

19 studies; 2 systematic reviews; 1 meta-analysis |

Classroom, online training, inpatient and outpatient (primary care, specialty care) |

|

| Failure To Rescue: Patient Monitoring Systems (PMS) |

|

8 studies; 3 systematic reviews |

Hospital (medical/surgical units) |

|

| Failure To Rescue: Rapid Response Teams |

|

4 studies; 3 systematic reviews; 3 meta-analyses |

Acute care hospitals |

|

|

Sepsis: Screening Tools |

|

26 studies; 2 systematic reviews |

Hospital, pre-hospital (emergency medical services [EMS]), and nursing homes |

|

| Sepsis: Patient Monitoring Systems |

|

15 studies; 4 systematic reviews |

Hospital (ICU, ED, general unit, telemetry, multiple units) |

|

| Clostridium difficile: Antimicrobial Stewardship |

|

17 studies; 3 meta-analyses; 2 systematic reviews |

Inpatient (hospitals, and long-term care facilities [LTCFs]/nursing homes) |

|

| Clostridium difficile: Testing |

|

25 studies; 7 systematic reviews |

Inpatient (hospitals), ED |

|

| Clostridium difficile: Surveillance |

|

16 studies; 2 systematic reviews |

Inpatient (hospitals and LTCFs), outpatient, and regional |

|

| Clostridium difficile: Hand Hygiene |

|

11 studies; 1 systematic review |

Inpatient (hospitals and LTCFs) |

|

| Clostridium difficile: Environmental Cleaning and Decontamination |

|

18 studies; 3 systematic reviews |

Inpatient (hospitals and LTCFs) |

|

| Clostridium difficile: Multicomponent Interventions |

|

8 studies; 3 systematic reviews |

Inpatient (hospitals, LTCFs) |

|

| Controlling Multidrug-Resistant Organisms (MDROs) and Preventing MDRO-Related Infection: Hand Hygiene for Controlling MDROs |

|

13 studies; 3 systematic reviews; 1 meta-analysis |

Hospitals (including intensive care transplant, dialysis, and general care units), LTCFs |

|

| Controlling Multidrug-Resistant Organisms (MDROs) and Preventing MDRO-Related Infection: Surveillance for Controlling MDROs |

|

20 studies; 2 systematic reviews; 1 meta-analysis |

Hospitals (including intensive care, neonatal intensive care, hematology/ oncology, and general care units) |

|

| Controlling Multidrug-Resistant Organisms (MDROs) and Preventing MDRO-Related Infection: Minimizing Exposure to Invasive Devices and Reducing Device-Associated Risks |

|

11 studies; 5 systematic reviews; 1 meta-analysis |

Inpatient settings (e.g., hospitals, LTCFs), outpatient settings (e.g., dialysis), and patient homes |

|

| Controlling Multidrug-Resistant Organisms (MDROs) and Preventing MDRO-Related Infection: Chlorhexidine Bathing for Controlling MDROs |

|

38 studies; 4 systematic reviews |

General healthcare settings, community settings, hospital settings (including intensive care, pediatric intensive care, transplant, and general care), LTCFs, and laboratory studies (for resistance) |

|

| Controlling Multidrug-Resistant Organisms (MDROs) and Preventing MDRO-Related Infection: Communication of Patient’s MDRO Status |

|

12 studies; 1 systematic review |

General healthcare settings, especially transfer of patients from one setting to another |

|

| Controlling Multidrug-Resistant Organisms (MDROs) and Preventing MDRO-Related Infection: Environmental Cleaning and Disinfection |

|

54 studies; 2 systematic reviews; 2 meta-analyses |

General healthcare settings (e.g., hospitals and LTCFs) |

|

| Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae: Contact Precautions To Prevent CRE |

|

18 studies; 3 systematic reviews |

General healthcare settings (e.g., hospitals and LTCFs) |

|

| Anticoagulants: Anticoagulation Management Service |

|

5 studies; 6 systematic reviews |

Ambulatory home-bound |

|

| Anticoagulants: Nomograms/Protocols for Novel Oral Anticoagulants |

|

4 studies | Group practice, academic medical center, community hospital |

|

| Anticoagulants: Anticoagulant Care in Transitions Between Hospital and Home |

|

5 studies | Discharge from ED |

|

| Diabetic Agents: Diabetes Protocol for Reducing Hypoglycemia |

|

11 studies | ED, ICU |

|

| Diabetic Agents: Teach-Back |

|

4 studies | Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC), academic medical center, outpatient clinic |

|

| Reducing Adverse Drug Events in Older Adults: Deprescribing |

|

13 studies | Residential care facility, community pharmacy, day center for senior citizens, skilled nursing facility, LTCF |

|

| Reducing Adverse Drug Events in Older Adults: Using the Screening Tool of Older Persons’ Potentially inappropriate Prescriptions (STOPP) Criteria |

|

14 studies |

Primary healthcare center, geriatric psychiatry admission unit, acute care admission, LTC, nursing homes, geriatrics outpatient clinic |

|

| Opioids: Opioid Stewardship |

|

14 studies; 1 systematic review | Primary care, health system ED, hospital, specialty |

|

|

Opioids: Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) Initiation |

|

25 studies; 1 systematic review |

ED, community practice, clinic for the homeless, primary care clinic, outpatient substance use disorder treatment center, FQHC |

|

|

Patient Identification Errors: Patient Identification Errors in the Operating Room |

|

8 studies; 1 systematic review |

Hospital operating room and theaters |

|

|

Infusion Pumps/Medication Error: Structured Process Change and Workflow Redesign |

|

6 studies |

Hospitals |

|

|

Infusion Pumps/Medication Error: Staff Education and Training |

|

5 studies |

Hospitals |

|

|

Alarm Fatigue: Safety Culture |

|

10 studies |

Hospitals; ICU; progressive care unit; neonatal intensive care unit; or telemetry, step-down, transplant cardiology, surgical, or surgical orthopedic units |

|

|

Alarm Fatigue: Risk Assessment |

|

8 studies |

Hospitals; ICU; progressive care unit; neonatal intensive care unit; step-down, transplant cardiology, surgical, or surgical orthopedic units |

|

|

Delirium: Screening and Assessment |

|

13 studies; |

All settings were included |

|

|

Delirium: Staff Education and Training |

|

16 studies |

All settings were included |

|

|

Delirium: Nonpharmacological Interventions To Prevent Delirium |

|

8 studies; 4 systematic reviews; 1 non-systematic review |

ICU |

|

|

Care Transitions:Transition of Care Models |

||||

|

BOOST: Better Outcomes for Older Adults through Safe Transitions |

|

3 studies |

Large hospitals |

|

|

CTI: Care Transition Intervention |

|

7 studies |

Acute care hospitals |

|

|

TCM: Transitional Care Model |

|

3 studies; 1 systematic review |

Community/outpatient, academic health system |

|

|

Venous Thromboembolism: Use of aspirin for VTE prophylaxis |

|

27 studies; |

Hospital, post-surgical care, tertiary care orthopedic referral centers; countries included USA, UK, China, Canada, and Korea |

|

|

Cross-Cutting Factors: Patient and Family Engagement (PFE) |

|

1 study; 2 systematic reviews |

Hospital |

|

|

Cross-Cutting Factors: Safety Culture |

||||

|

Leadership WalkRounds |

|

4 studies; |

Hospital |

|

|

Team Training |

|

8 studies; |

Hospital, VA facilities, rehabilitation unit in long-term care facility |

|

|

Comprehensive unit-based safety program (CUSP) |

|

6 studies; |

Hospital |

|

|

Multiple Interventions |

|

1 study |

Hospital |

|

|

Cross-Cutting Factors: Clinical Decision Support (CDS) |

NA |

26 studies; |

All settings included in searches |

|

|

Cross-Cutting Factors: Cultural Competency |

|

7 studies; |

Inpatient, outpatient, and home health |

|

|

Cross-Cutting Factors: Monitoring, Audit, and Feedback |

NA |

28 studies; 3 systematic reviews; 1 non-systematic review |

All settings included in searches |

|

|

Cross-Cutting Factors: Teamwork and Team Training |

||||

|

Crew Resource Management (CRM) |

|

6 studies; |

Hospital |

|

|

Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety (TeamSTEPPS®) |

|

6 studies; |

Hospital, ED, psychiatric hospital |

|

|

Veterans Health Administration Medical Team Training |

|

2 studies; |

VA facilities |

|

|

Team Simulation |

|

6 studies; |

Tertiary care medical center, teaching hospital, VA facility |

|

|

Brief/Debrief |

|

3 studies |

ED, surgical department, ICU |

|

|

Handoff |

|

3 studies |

Hospital (surgical units, neurointerventional suite) |

|

|

Cross-Cutting Factors: Staff Education and Training |

||||

|

Simulation-Based Medical Education for Residents and Fellows |

|

5 studies; |

Teaching hospital, tertiary teaching hospital |

|

|

Simulation as Part of Continuing Education of Nurses |

|

2 studies |

Children’s hospital, teaching hospital |

|

ES.5 Discussion

This report covers 47 PSPs chosen for the high-impact harms they address and interest in the status of their use. The harms include diagnostic errors, failure to rescue, sepsis, infections due to multi-drug resistant organisms, adverse drug events, and nursing-sensitive conditions. While going through the process of selecting PSPs to address specific harm areas, it became evident that several commonly recommended practices should also be reviewed. These cross-cutting practices are: improving safety culture, teamwork and team training, clinical decision support, patient and family engagement, cultural competency, staff education and training, and monitoring, audit, and feedback. All of the harm-specific PSPs and cross-cutting PSPs included in this report underwent focused systematic reviews to establish the current evidence base for their use.

The most significant harms patients face continue to be found in higher acuity settings, such as the ED and ICU, and the research is biased toward those settings. One “setting” that poses a unique threat to patients is the transition between one setting and another: the hospital to the outpatient setting, in particular. As we move out from the silos required in setting-specific research, the research needs to address these gaps.

Regardless of setting, several themes emerged from the report:

- More than one PSP can be used to reduce a given harm. The PSPs presented in the report are those that the project TEP and AG felt were ready for a fresh review of the literature or that were relatively new and needed to have an evidence base established. The PSPs in the report are not intended to be an inclusive list.

- Selecting a particular PSP should be based on the root cause of the harm. If a facility is experiencing an increase in sepsis mortality, the root cause may be a lack of recognition of patients with sepsis arriving to the ED. In another facility, it may be due to lack of monitoring of patients who are experiencing deterioration on a medical-surgical unit.

- When using a specific PSP, consideration must be given to potential new harms that can be introduced. For example, strategies to improve anticoagulation-related events must be balanced with strategies used to reduce venous thromboembolism.

- PSPs are not implemented in isolation and are often part of a broader safety strategy. The strategy often relies on a strong safety culture, teamwork, communication, and involvement of the patient and family. These cross-cutting practices are the foundation for success.

- The context in which a PSP is implemented determines success. Understanding the impact of context through rigorous, large-scale research studies is difficult. It is extremely difficult, and sometimes may be impossible, to design a study that takes into consideration all potential contextual factors, such as staffing, other PSPs in place, safety culture, and leadership engagement, and to control for those factors across enough sites to make the findings generalizable.

ES.6 Limitations

There are several limitations to conducting such a broad review of the literature as found in this report.

As our understanding of patient safety expands, there is an increasing amount of published research, with most showing positive effects of the intervention under question (i.e., publication bias). With the paucity of recent randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in the literature and the reliance on pre-post studies and observational studies, it is difficult to assess the impact of the biases introduced by study design on the findings.

The low number of RCTs in the patient safety literature is also a limitation in conducting focused systematic reviews such as those found in this report. Many of the PSPs under examination have been implemented in some form. Staff are aware of the implementation of the PSPs, so being blinded to the intervention is not possible. Since PSPs are typically implemented across an entire facility rather than a single unit, finding a control group for comparison can be difficult.

Lastly, some of the PSPs addressed were introduced as part of multicomponent interventions (e.g., strategies to reduce C. difficile infections). When a specific PSP is part of a multicomponent intervention, it is difficult to ascertain which of the components is the driver for success.

ES.7 Conclusions

This report presents reviews of 47 different PSPs covering a wide variety of harms across multiple settings. The amount of research in patient safety has exponentially grown since the second report was published. PSPs that are more well-established are now being investigated in light of emerging harms, such as PSPs related to infection prevention to address multi-drug resistant organisms. Similarly, emerging PSPs are being investigated for use to address well-established harms, such as the use of clinical decision support to reduce diagnostic errors.

It is clear that many factors impact the success of any PSP on reducing harm. Patient safety culture, teamwork and communication, person and family engagement, providing culturally competent care, reinforcing good practice with education and training, and learning from data are all necessary to ensure success.

ES.8 Future Research Needs

It is clear from the reviews of these PSPs that the importance of context for implementation cannot be overstated. Context plays a large role in the successful uptake and use of a PSP. Setting, safety culture, staffing, and other organizational factors often contribute to harm reduction as much as a PSP itself. More implementation research needs to be conducted across all of the PSPs to understand and work within real-world constraints, rather than conducting studies that may be rigorous but are stripped of that context. We often know what to do, and in these cases, the challenge now is to implement PSPs into a specific facility or setting and have them succeed.

References

- Shojania KG, Duncan BW, McDonald KM, Wachter RM, eds. Making Health Care Safer: A Critical Analysis of Patient Safety Practices. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 43 (Prepared by the University of California at San Francisco–Stanford Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No.290-97-0013). AHRQ Publication No.01-E058. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. July 2001. https://archive.ahrq.gov/clinic/ptsafety/pdf/ptsafety.pdf.

- Shekelle PG, Wachter RM, Pronovost PJ, Schoelles K, McDonald KM, Dy SM, Shojania K, Reston J, Berger Z, Johnsen B, Larkin JW, Lucas S, Martinez K, Motala A, Newberry SJ, Noble M, Pfoh E, Ranji SR, Rennke S, Schmidt E, Shanman R, Sullivan N, Sun F, Tipton K, Treadwell JR, Tsou A, Vaiana ME, Weaver SJ, Wilson R, Winters BD. Making Health Care Safer II: An Updated Critical Analysis of the Evidence for Patient Safety Practices. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 211. (Prepared by the Southern California-RAND Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-2007-10062-I.) AHRQ Publication No.13-E001-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. March 2013. https://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/evidence-based-reports/ptsafetyuptp.html#Report.

- National Quality Forum (NQF). Safe Practices for Better Healthcare–2009 Update. Washington, DC; 2009. https://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2009/03/Safe_Practices_for_Better_Healthcare %E2%80%932009_Update.aspx.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Patient Safety Network. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/. Accessed January 23, 2020.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The National Quality Strategy: Fact Sheet. https://www.ahrq.gov/workingforquality/about/nqs-fact-sheets/fact-sheet.html. Accessed January 23, 2020.

- The Joint Comission. National Patient Safety Goals. https://www.jointcommission.org/standards/national-patient-safety-goals/. Accessed January 23, 2020.

- National Quality Forum (NQF). Patient Safety 2015 Final Report. Washington, DC; 2015.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. The Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (VBP) Program https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment- Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/HVBP/Hospital-Value-Based-Purchasing. Accessed January 23, 2020.

- ECRI Institute. Executive Brief Top 10 Patient Safety Concerns for Healthcare Organizations 2017. Plymouth Meeting, PA; 2017. https://www.ecri.org/EmailResources/PSRQ/Top10/2017_PSTop10_ExecutiveBrief.pdf.

- ECRI Institute. Executive Brief Top 10 Patient Safety Concerns for Healthcare Organizations 2016. Plymouth Meeting, PA; 2016. https://www.ecri.org/EmailResources/PSRQ/Top10/2016_Top10_ExecutiveBrief_final.pdf.

- Vaidya A, Zimmerman, Bean M. 10 Top Patient Safety Issues for 2018. https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/10-top-patient-safety-issues-for-2018.html. Accessed January 23, 2020.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Partnership for Patients. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/partnership-for-patients/. Accessed January 23, 2020.

- Whitlock EP, Lin JS, Chou R, et al. Using existing systematic reviews in complex systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(10):776-82. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-10-200805200-00010.

- Shea B, Reeves B, Wells G, et al. AMSTAR 2: A crticial appraisal tool for systematic review that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4008.

- Blackman C, Chartrand J, Dingwall O, et al. Effectiveness of person-and family-centered care transition interventions: a systematic review protocol. Bio Med Central. 2017 6:158. doi: 10.1186/s13643-017-0554-z

- Viswanathan M, Ansari MT, Berkman ND, et al. Assessing the Risk of Bias of Individual Studies in Systematic Reviews of Health Care Interventions. Methods Guide for Effectiveness And Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. AHRQ Publication No. 12-EHC047-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. March 2012. https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/methods-guidance-bias-individual-studies_methods.pdf

- Berkman ND, Lohr KN, Ansari M, et al. Grading the Strength of a Body of Evidence When Assessing Health Care Interventions for the Effective Health Care Program of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: An Update. Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. (Prepared by the RTI-UNC Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-2007-10056-I). AHRQ Publication No. 13(14)-EHC130-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. November 2013.

- Owens DK, Lohr KN, Atkins D, et al. AHRQ series paper 5: Grading the strength of a body of evidence when comparing medical interventions--Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the Effective Health-Care Program. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(5):513-23. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.03.009.

- Atkins D, Eccles M, Flottorp S, et al. Systems for grading the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations: Critical appraisal of existing approaches the grade working group. BMC Health Serv Res. 2004;4(1):38. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-4-38.