Chartbook on Healthy Living: Slide Presentation

National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report

Slide 1

National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report

Chartbook on Healthy Living

April 2016

Slide 2

Organization of the Chartbook on Healthy Living

- Part of a series related to the National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report (QDR).

- Contents:

- Overview of the QDR.

- Overview of Healthy Living, one of the priorities of the National Quality Strategy.

- Summary of trends and disparities in Healthy Living from the QDR.

- Tracking of individual measures of Healthy Living:

- Maternal and Child Health Care.

- Lifestyle Modification.

- Clinical Preventive Services.

- Functional Status Preservation and Rehabilitation.

- Supportive and Palliative Care.

Slide 3

National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report

- Annual report to Congress mandated in the Healthcare Research and Quality Act of 1999 (P.L. 106-129).

- Provides a comprehensive overview of:

- Quality of health care received by the general U.S. population.

- Disparities in care experienced by different racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups.

- Assesses the performance of our health system and identifies areas of strengths and weaknesses along three main axes:

- Access to health care.

- Quality of health care.

- Priorities of the National Quality Strategy.

Slide 4

National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report

- Based on more than 250 measures of quality and disparities covering a broad array of health care services and settings.

- Includes data from 2015 QDR, which generally cover 2001-2013.

- Produced with the help of an Interagency Work Group led by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and submitted on behalf of the Secretary of Health and Human Services.

Slide 5

Chartbooks Organized Around Priorities of the National Quality Strategy

- Making care safer by reducing harm caused in the delivery of care.

- Ensuring that each person and family is engaged as partners in their care.

- Promoting effective communication and coordination of care.

- Promoting the most effective prevention and treatment practices for the leading causes of mortality, starting with cardiovascular disease.

- Working with communities to promote wide use of best practices to enable healthy living.

- Making quality care more affordable for individuals, families, employers, and governments by developing and spreading new health care delivery models.

Note: Healthy Living is one of the six national priorities identified by the National Quality Strategy (http://www.ahrq.gov/workingforquality/index.html).

Slide 6

Priority 5: Working with communities to promote wide use of best practices to enable healthy living

Long-Term Goals

The National Quality Strategy has identified three long-term goals related to healthy living:

- Promote healthy living and well-being through community interventions that result in improvement of social, economic, and environmental factors.

- Promote healthy living and well-being through interventions that result in adoption of the most important healthy lifestyle behaviors across the lifespan.

- Promote healthy living and well-being through receipt of effective clinical preventive services across the lifespan in clinical and community settings.

Note:

- The broad goal of promoting better health is one that is shared across the country, whether it is promoting healthy behaviors, such as being tobacco free, or fostering healthy environments that make it easier to exercise and get access to healthy food.

- Successful efforts to improve these health factors rely on implementing evidence-based interventions through strong partnerships between local health care providers, public health professionals, and individuals.

Slide 7

Chartbook Contents

- This chartbook includes:

- Summary of trends across measures of Healthy Living from the QDR.

- Figures illustrating select measures of Healthy Living.

- Introduction and Methods contains information about methods used in the chartbook.

- A Data Query tool (http://nhqrnet.ahrq.gov/inhqrdr/data/query) provides access to all data tables.

Slide 8

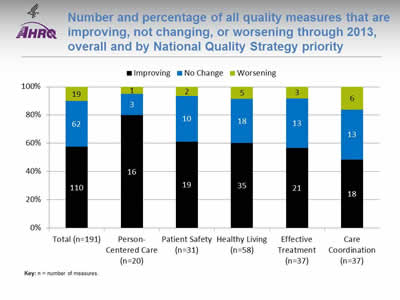

Number and percentage of all quality measures that are improving, not changing, or worsening through 2013, overall and by National Quality Strategy priority

Image: Chart shows number and percentage of all quality measures that are improving, not changing, or worsening through 2013:

| Quality Measures | Improving | No Change | Worsening |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n=191) | 110 | 62 | 19 |

| Person-Centered Care (n=20) | 16 | 3 | 1 |

| Patient Safety (n=31) | 19 | 10 | 2 |

| Healthy Living (n=58) | 35 | 18 | 5 |

| Effective Treatment (n=37) | 21 | 13 | 3 |

| Care Coordination (n=37) | 18 | 13 | 6 |

Key: n = number of measures.

Notes: For most measures, trend data are available from 2001-2002 through 2013. For each measure with at least four estimates over time, unweighted log-linear regression is used to calculate average annual percentage change and to assess statistical significance. Measures are aligned so that positive change indicates improved access to care.

- Improving = Rates of change are positive at 1% per year or greater and are statistically significant.

- No Change = Rates of change are less than 1% per year or are not statistically significant.

- Worsening = Rates of change are negative at -1% per year or greater and are statistically significant.

- Through 2013, across a broad spectrum of measures of health care quality, 60% showed improvement (black).

- About 80% of measures of Person-Centered Care improved.

- About 60% of measures of Effective Treatment, Healthy Living, and Patient Safety improved.

- Fewer than half of measures of Care Coordination improved.

- There are insufficient numbers of reliable measures of Care Affordability to summarize this way.

Slide 9

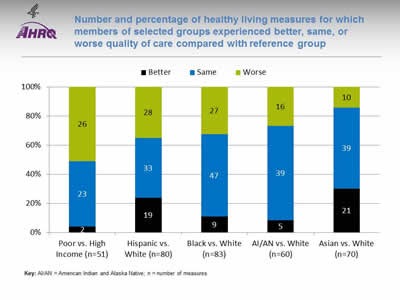

Number and percentage of healthy living measures for which members of selected groups experienced better, same, or worse quality of care compared with reference group

Image: Chart shows number and percentage of healthy living measures for which members of selected groups experienced better, same, or worse quality of care:

| Quality | Poor vs. High Income (n=51) | Hispanic vs. White (n=80) | Black vs. White (n=83) | AI/AN vs. White (n=60) | Asian vs. White (n=70) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Better | 2 | 19 | 9 | 5 | 21 |

| Same | 23 | 33 | 47 | 39 | 39 |

| Worse | 26 | 28 | 27 | 16 | 10 |

Key: AI/AN = American Indian and Alaska Native; n = number of measures.

Notes: Poor indicates family income less than the Federal poverty level; High Income indicates family income four times the Federal poverty level or greater. Numbers of measures differ across groups because of sample size limitations. For most measures, data from 2012 are shown. The relative difference between a selected group and its reference group is used to assess disparities.

- Better = Selected group received better quality of care than reference group. Differences are statistically significant, are equal to or larger than 10%, and favor the selected group.

- Same = Selected group and reference group received about the same quality of care. Differences are not statistically significant or are smaller than 10%.

- Worse = Selected group received worse quality of care than reference group. Differences are statistically significant, are equal to or larger than 10%, and favor the reference group.

- People in poor households received worse care than people in high-income households for about half of healthy living measures.

- Hispanics, Blacks, and American Indians and Alaska Natives received worse care than Whites for about one-third of health living measures.

Slide 10

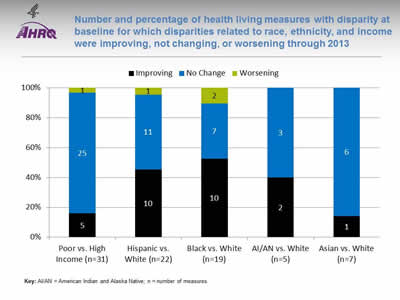

Number and percentage of health living measures with disparity at baseline for which disparities related to race, ethnicity, and income were improving, not changing, or worsening through 2013

Image: Chart shows number and percentage of health living measures with disparity at baseline for which disparities related to race, ethnicity, and income were improving, not changing, or worsening through 2013:

| Disparity | Poor vs. High Income (n=31) | Hispanic vs. White (n=22) | Black vs. White (n=19) | AI/AN vs. White (n=5) | Asian vs. White (n=7) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Worsening | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| No Change | 25 | 11 | 7 | 3 | 6 |

| Improving | 5 | 10 | 10 | 2 | 1 |

Key: AI/AN = American Indian and Alaska Native; n = number of measures.

Notes: Poor indicates family income less than the Federal poverty level; High Income indicates family income four times the Federal poverty level or greater. Number of measures differs across groups because of sample size limitations. For most measures, trend data are available from 2001-2002 to 2013.

For each measure with a disparity at baseline, average annual percentage changes were calculated for select populations and reference groups. Measures are aligned so that positive rates indicate improvement in care. Differences in rates between groups were used to assess trends in disparities.

- Worsening = Disparities are getting larger. Differences in rates between groups are statistically significant and reference group rates exceed population rates by at least 1% per year.

- No Change = Disparities are not changing. Differences in rates between groups are not statistically significant or differ by less than 1% per year.

- Improving = Disparities are getting smaller. Differences in rates between groups are statistically significant and population rates exceed reference group rates by at least 1% per year.

- Through 2013, about 40% of disparities at baseline for Hispanics and American Indians and Alaska Natives were getting smaller (black).

- More than half of disparities at baseline for Blacks were getting smaller.

- About 15% of disparities at baseline for Asians and people living in poor households were getting smaller.

Slide 11

Healthy Living Measures With Disparities That Were Eliminated

- Hispanic vs. Non-Hispanic White Gap:

- Adults with obesity who ever received advice about eating fewer high-fat or high-cholesterol foods.

- Home health care patients who get better at bathing.

- Black vs. White Gap:

- Adults with obesity age 20 and over who had been told by a doctor or health professional that they were overweight.

- Children ages 19-35 months who received 3+ doses of polio vaccine.

- Children ages 19-35 months who received 1+ doses of measles-mumps-rubella vaccine.

Slide 12

Healthy Living Measures With Disparities That Were Eliminated

- American Indian and Alaska Native vs. White Gap:

- Children ages 2-17 for whom a health provider gave advice about the amount and kind of exercise, sports, or physically active hobbies they should have.

- Children ages 2-17 for whom a health provider gave advice about healthy eating.

- Poor vs. High Income Gap:

- Adults with obesity who ever received advice from a health professional to exercise more.

- Adolescent females ages 13-15 years who received 3+ doses of human papillomavirus vaccine.

Slide 13

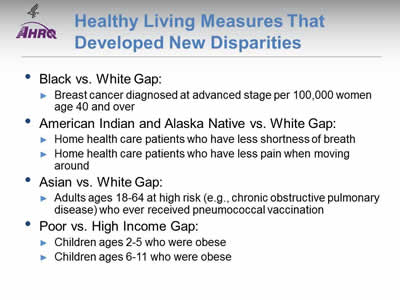

Healthy Living Measures That Developed New Disparities

- Black vs. White Gap:

- Breast cancer diagnosed at advanced stage per 100,000 women age 40 and over.

- American Indian and Alaska Native vs. White Gap:

- Home health care patients who have less shortness of breath.

- Home health care patients who have less pain when moving around.

- Asian vs. White Gap:

- Adults ages 18-64 at high risk (e.g., chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) who ever received pneumococcal vaccination.

- Poor vs. High Income Gap:

- Children ages 2-5 who were obese.

- Children ages 6-11 who were obese.

Slide 14

Measures of Healthy Living

- This chartbook tracks measures of Healthy Living through 2013, overall and for populations defined by age, race, ethnicity, income, education, insurance, and number of chronic conditions.

- Measures of Healthy Living include:

- Receipt of processes that reflect high-quality preventive and supportive care.

- Outcomes related in part to receipt of high-quality preventive and supportive care.

Slide 15

Services That Promote Healthy Living

- Much valuable health care is delivered to prevent disease, disability, and discomfort rather than to treat specific clinical conditions.

- These services improve health and quality of life and are often better characterized by stage over a lifespan rather than by organ system.

Slide 16

Services Covered in This Chartbook

- This chartbook is organized around five types of health care services that support healthy living but typically cut across clinical conditions:

- Maternal and Child Health Care.

- Lifestyle Modification.

- Clinical Preventive Services.

- Functional Status Preservation and Rehabilitation.

- Supportive and Palliative Care.

Slide 17

Chartbook on Healthy Living

Maternal and Child Health Care

Slide 18

Maternal and Child Health Care Measures

- Access:

- Periods of uninsurance.

- Effectiveness:

- Prenatal care.

- Receipt of recommended immunizations by young children.

- Children's vision screening.

- Well-child visits in the last year.

- Receipt of meningococcal vaccine by adolescents.

- Receipt of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination by adolescents.

Slide 19

Maternal and Child Health Care Measures

- Person-Centered Care:

- Children who had a doctor's office or clinic visit in the last 12 months who reported poor communication with health providers.

- Patient Safety:

- Birth trauma—injury to neonates.

- Care Coordination:

- Children and adolescents whose health provider usually asks about prescription medications and treatments from other doctors.

- Emergency department (ED) visits with a principal diagnosis related to mental health, alcohol, or substance abuse.

- ED visits for asthma.

Slide 20

Access: Children and Adolescents With Periods of Uninsurance

- Coverage gaps ("uninsurance") are a significant factor in children's access to and use of care, as well as their health outcomes.1-3

- Resources through the Children's Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act (CHIPRA) are designed to increase Medicaid/CHIP enrollment:

- Outreach programs.

- Simplified enrollment strategies.4

- Coverage gaps are still found for as many as 40% of new CHIP enrollees5 despite changes in State enrollment, renewal, and outreach processes.

Slide 21

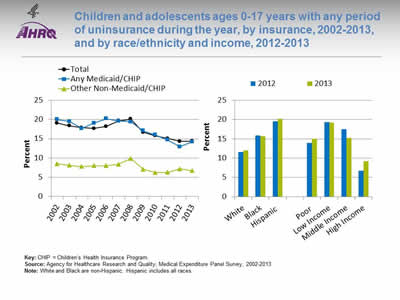

Children and adolescents ages 0-17 years with any period of uninsurance during the year, by insurance, 2002-2013, and by race/ethnicity and income, 2012-2013

Image: Charts show children and adolescents ages 0-17 years with any period of uninsurance during the year, by insurance and by race/ethnicity and income:

Left Chart:

| Year | Total | Other Non-Medicaid/CHIP | Any Medicaid/CHIP |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 19.1 | 8.5 | 20 |

| 2003 | 18.4 | 8.1 | 19.5 |

| 2004 | 17.9 | 7.8 | 17.7 |

| 2005 | 17.7 | 8 | 19.1 |

| 2006 | 18.2 | 8 | 20.2 |

| 2007 | 19.7 | 8.4 | 19.6 |

| 2008 | 20.1 | 9.9 | 19.4 |

| 2009 | 16.7 | 7.1 | 17.1 |

| 2010 | 15.8 | 6.2 | 16 |

| 2011 | 15.1 | 6.3 | 14.7 |

| 2012 | 14.3 | 7.2 | 12.9 |

| 2013 | 14.4 | 6.7 | 14.2 |

Right Chart:

| Characteristics | 2012 | 2013 |

|---|---|---|

| White | 11.6 | 12 |

| Black | 15.9 | 15.7 |

| Hispanic | 19.6 | 20.2 |

| Poor | 13.9 | 15 |

| Low Income | 19.3 | 19.2 |

| Middle Income | 17.5 | 15.3 |

| High Income | 6.7 | 9.2 |

Key: CHIP = Children's Health Insurance Program.

Source: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2002-2013.

Notes: White and Black are non-Hispanic. Hispanic includes all races.

- Overall: In 2013, the percentage of children and adolescents ages 0-17 with any period of uninsurance during the year was 14.4%.

- Trends:

- The overall percentage of children and adolescents ages 0-17 years with any period of uninsurance during the year declined from 19.1% in 2002 to 14.4% in 2013.

- Among children and adolescents with any Medicaid or CHIP insurance, the percentage with any period of uninsurance during the year declined from 20.0% in 2002 to 14.2% in 2013.

- Groups With Disparities:

- In 2012 and 2013, White children were less likely to have a period of uninsurance than Black and Hispanic children.

- In 2012 and 2013, children in families with high incomes were less likely than children in every other income category to have a period of uninsurance.

Slide 22

Effectiveness Measures

- Early and adequate prenatal care.

- Receipt of recommended immunizations by young children.

- Children's vision screening.

- Well-child visits in the last year.

- Receipt of meningococcal vaccine by adolescents.

- Receipt of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination by adolescents.

Slide 23

Prevention: Early and Adequate Prenatal Care

- A Healthy People 2020 objective is for 77.6% of pregnant women to receive early and adequate prenatal care:

- Definition is based on Adequacy of Prenatal Care Utilization Index.

- For a given pregnancy, the target number of prenatal visits considered adequate is determined by the start date of prenatal care and the infant's gestational age at birth.

Slide 24

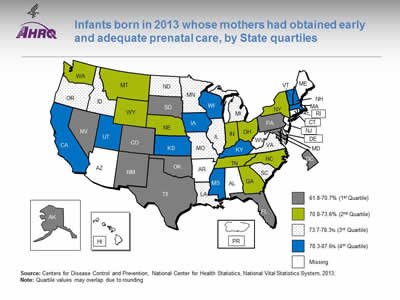

Infants born in 2013 whose mothers had obtained early and adequate prenatal care, by State quartiles

Image: Map of the United States is color-coded by state to show overall rankings by quartile of infants born to women who received early and adequate prenatal care.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System, 2013.

Notes: Quartile values may overlap due to rounding.

Because of changes between the 1998 and 2003 versions of birth certificates, prenatal care timing and adequacy were evaluated only for the District of Columbia and the 41 States using the 2003 standard birth certificate for all of 2013. Data for 2013 were only available for these 42 State-equivalent jurisdictions, so national estimates were not generated. However, these 42 jurisdictions accounted for more than 86% of live births in the United States in 2013. The State-equivalent jurisdictions (AL, AR, AZ, CT, HI, ME, NJ, PR, RI, and WV) not using the 2003 version of the birth certificate did not have data available for this measure and are categorized as "missing" on the map.

To classify the adequacy of prenatal care services, the reported number of visits is compared with the expected number of visits for the period between when care began and the delivery date. Completeness of reporting varies by item and State. In 2013, two States were missing responses on more than 10% of the birth certificates (GA-15.9%; NV-12.9%). The impact of the comparatively high level of unknown data is not clear. Comparisons including information from these States should be made with caution. More detailed information is available in the 2013 Natality Data Users Guide: ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/DVS/natality/UserGuide2013.pdf (1.4 MB).

- Overall: This map shows overall rankings by quartile in the percentage of infants born to women who received early and adequate prenatal care in 2013, for Washington, DC, and 41 States. Values ranged from 61.8% to 87.6%.

- Differences by State: Interquartile ranges follow:

- First quartile (lowest): 61.8%-70.7% (AK, CO, DC, FL, MD, NM, NV, OK, PA, SD, TX).

- Second quartile (second lowest): 70.8%-73.6% (GA, IN, MT, NE, NY, NC, OH, TN, WA, WY).

- Third quartile (second highest): 73.7%-78.3% (DE, ID, IL, LA, MI, MN, MO, ND, OR, SC, VA).

- Fourth quartile (highest): 78.3%-87.6 % (CA, IA, KS, KY, MA, MS, NH, UT, VT, WI).

Slide 25

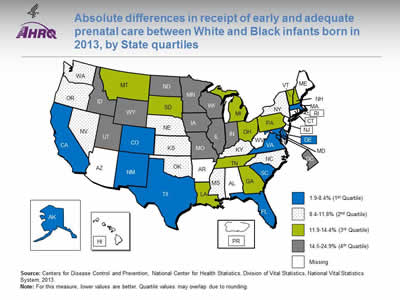

Absolute differences in receipt of early and adequate prenatal care between White and Black infants born in 2013, by State quartiles

Image: Map of the United States is color-coded by state to show rankings by quartile for the absolute differences between percentages of White and Black infants whose mothers received early and adequate prenatal care.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, Division of Vital Statistics, National Vital Statistics System, 2013.

Notes: For this measure, lower values are better. Quartile values may overlap due to rounding.

Because of changes between the 1998 and 2003 versions of birth certificates, prenatal care timing and adequacy were evaluated only for the District of Columbia and the 41 States using the 2003 standard birth certificate for all of 2013. Data for 2013 were only available for these 42 State-equivalent jurisdictions, so national estimates were not generated. However, these 42 jurisdictions accounted for more than 86% of live births in the United States in 2013. The State-equivalent jurisdictions (AL, AR, AZ, CT, HI, ME, NJ, PR, RI, and WV) not using the 2003 version of the birth certificate did not have data available for this measure and are categorized as "missing" on the map.

To classify the adequacy of prenatal care services, the reported number of visits is compared with the expected number of visits for the period between when care began and the delivery date. Completeness of reporting varies by item and State. In 2013, two States were missing responses on more than 10% of the birth certificates (GA-15.9%; NV-12.9%). The impact of the comparatively high level of unknown data is not clear. Comparisons including information from these States should be made with caution. More detailed information is available in the 2013 Natality Data Users Guide: ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/DVS/natality/UserGuide2013.pdf (1.4 MB).

- Overall: This map shows overall State-equivalent rankings by quartile for the absolute differences between percentages of White and Black infants born in 2013 whose mothers obtained early and adequate prenatal care. Differences ranged from 1.9% to 24.9% (lower is better).

- Differences by State: Interquartile ranges follow:

- First quartile (smallest absolute difference): 1.9%-8.4% (AK, CA, CO, DE, FL, MA, MD, NM, SC, TX, VA).

- Second quartile: 8.4%-11.8 (KS, KY, MS, NE, NV, NY, NC, OK, OR, WA).

- Third quartile: 11.9%-14.4% (GA, LA, MI, MT, NH, OH, PA, SD, TN, VT).

- Fourth quartile (largest absolute difference): 14.5%-24.9% (DC, ID, IL, IN, IA, MN, MO, ND, UT, WI, WY).

Slide 26

Prevention: Receipt of Recommended Vaccinations by Young Children

- Immunizations reduce mortality and morbidity by:

- Protecting recipients from illness.

- Protecting others in the community who are not vaccinated.

- Beginning in 2007, seven vaccines were recommended to be completed by ages 19-35 months. The recommended vaccines are:

- Diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccine.

- Polio vaccine.

- Measles-mumps-rubella vaccine.

- Haemophilus influenzae type B vaccine.

- Hepatitis B vaccine.

- Varicella vaccine.

- Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine.

- The Healthy People 2020 target is 80% coverage in the population ages 19-35 months.

Note:

- These vaccines constitute the 4:3:1:3:3:1:4 vaccine series tracked in Healthy People 2020.

Slide 27

Prevention: Receipt of Recommended Vaccinations by Young Children

The U.S. Surgeon General, Dr. Vivek H. Murthy, and Elmo want everyone to stay healthy and get vaccinated! https://youtu.be/viS1ps0r4K0

Slide 28

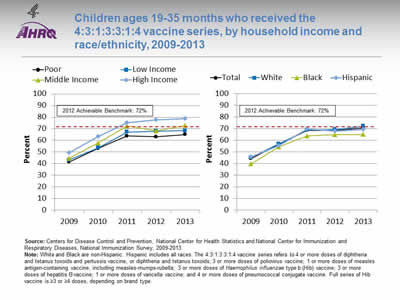

Children ages 19-35 months who received the 4:3:1:3:3:1:4 vaccine series, by household income and race/ethnicity, 2009-2013

Image: Charts show children ages 19-35 months who received the 4:3:1:3:3:1:4 vaccine series, by household income and race/ethnicity:

Left Chart:

| Income | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poor | 41.6 | 53.1 | 63.9 | 63.1 | 65.0 |

| Low Income | 43.1 | 53.7 | 67.2 | 68.0 | 68.5 |

| Middle Income | 44.6 | 57.8 | 72.4 | 68.1 | 72.7 |

| High Income | 49.3 | 63.5 | 75.2 | 77.7 | 78.9 |

Right Chart:

| Race / Ethnicity | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 44.3 | 56.6 | 68.5 | 68.4 | 70.4 |

| Hispanic | 45.9 | 55.5 | 69.5 | 67.8 | 69.3 |

| Black | 39.6 | 54.5 | 63.7 | 64.8 | 65.0 |

| White | 45.2 | 56.9 | 68.8 | 69.3 | 72.1 |

2012 Achievable Benchmark: 72%.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics and National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, National Immunization Survey, 2009-2013.

Notes: White and Black are non-Hispanic. Hispanic includes all races. The 4:3:1:3:3:1:4 vaccine series refers to 4 or more doses of diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and pertussis vaccine, or diphtheria and tetanus toxoids; 3 or more doses of poliovirus vaccine; 1 or more doses of measles antigen-containing vaccine, including measles-mumps-rubella; 3 or more doses of Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) vaccine; 3 or more doses of hepatitis B vaccine; 1 or more doses of varicella vaccine; and 4 or more doses of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Full series of Hib vaccine is ≥3 or ≥4 doses, depending on brand type.

- Overall: in 2013, the percentage of children ages 19-35 months who received the 4:3:1:3:3:1:4 vaccination series was 70.4%.

- Trends: From 2009 to 2013, the percentage of children ages 19-35 months who received the 4:3:1:3:3:1:4 vaccination series improved overall and for all income and racial/ethnic groups.

- Groups With Disparities:

- In 2013, the percentage of children ages 19-35 months who received all the recommended vaccines was lower for children from poor, low and middle income families compared to those from high income families.

- In 2013, the percentage of Black children (65.0%) ages 19-35 who received all the recommended vaccines was lower compared to White children (72.1%).

- Achievable Benchmark:

- The 2012 top 5 State achievable benchmark was 72%. The top 5 States that contributed to the achievable benchmark are Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Ohio.

- Children from high-income households and middle-income households have achieved the benchmark. White children also have achieved the benchmark.

- Children overall and children from poor and low-income households could achieve the benchmark in approximately a year. Black and Hispanic children also could achieve the benchmark within a year.

Slide 29

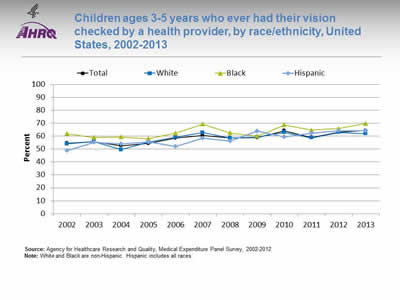

Prevention: Children's Vision Screening

- Vision checks for children may detect problems of which children and their parents were previously unaware.6

- Early detection also improves the chances that corrective treatments will be effective.6

Slide 30

Children ages 3-5 years who ever had their vision checked by a health provider, by race/ethnicity, United States, 2002-2013

Image: Chart shows children ages 3-5 years who ever had their vision checked by a health provider, by race/ethnicity:

| Year | Total | White | Black | Hispanic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 54.5 | 54.0 | 61.9 | 48.9 |

| 2003 | 55.8 | 55.6 | 59.0 | 55.4 |

| 2004 | 52.6 | 49.6 | 59.3 | 54.0 |

| 2005 | 54.4 | 55.4 | 58.1 | 55.7 |

| 2006 | 58.5 | 59.2 | 62.4 | 52.2 |

| 2007 | 60.5 | 62.8 | 69.3 | 58.5 |

| 2008 | 58.8 | 58.6 | 62.6 | 56.1 |

| 2009 | 58.9 | 59.2 | 60.1 | 64.1 |

| 2010 | 64.2 | 62.9 | 68.7 | 59.6 |

| 2011 | 59.1 | 58.8 | 64.7 | 62.3 |

| 2012 | 63.0 | 62.9 | 66.0 | 64.2 |

| 2013 | 64.4 | 61.9 | 69.8 | 64.2 |

Source: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2002-2012.

Notes: White and Black are non-Hispanic. Hispanic includes all races.

- Trends:

- From 2002 to 2013, the percentage of children ages 3-5 years who had ever received a vision check by a health provider increased from 54.5% to 64.4%.

- Among White children ages 3-5 years, the percentage who had ever received a vision check by a health provider increased from 54% in 2002 to 61.9% in 2013. The percentage also increased for Hispanic children from 48.9% in 2002 to 64.2% in 2013. However, there was no statistically significant increase for Black children (61.9% in 2002 and 69.8% in 2013).

- Groups With Disparities:

- In 2013, there were no statistically significant differences between White, Black, and Hispanic children in the percentage who had ever received a vision check (61.9%, 69.8%, and 64.2%, respectively).

Slide 31

Prevention: Well-Child Visits in the Last Year

- The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends annual preventive health care visits for all children.7 Current (2014) recommendations for visits:

- 7 well-child visits before 12 months of age.

- 6 well-child visits between 12 and 36 months of age.

- 1 well-child visit per year from ages 3 to 21 years.

- The Affordable Care Act requires insurance plans to cover well-child visits with no copayments or deductibles.8

- A Healthy People 2020 objective is to improve the rate of adolescent well visits.9

Slide 32

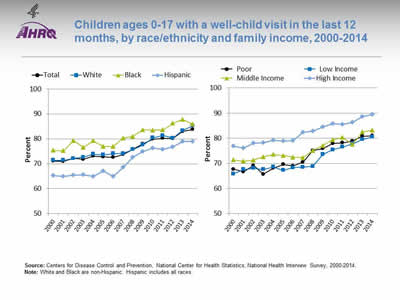

Children ages 0-17 with a well-child visit in the last 12 months, by race/ethnicity and family income, 2000-2014

Image: Charts show children ages 0-17 with a well-child visit in the last 12 months, by race/ethnicity and family income:

Left Chart:

| Year | Total | White | Black | Hispanic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 71.0 | 71.3 | 75.4 | 65.3 |

| 2001 | 71.0 | 71.4 | 75.2 | 64.9 |

| 2002 | 72.1 | 72.1 | 79.4 | 65.4 |

| 2003 | 71.8 | 72.7 | 76.5 | 65.6 |

| 2004 | 73.0 | 73.9 | 79.2 | 64.9 |

| 2005 | 72.8 | 73.6 | 77.0 | 67.1 |

| 2006 | 72.5 | 74.0 | 76.9 | 64.9 |

| 2007 | 73.7 | 74.1 | 80.3 | 68.5 |

| 2008 | 75.8 | 75.7 | 81.0 | 72.6 |

| 2009 | 78.0 | 77.6 | 83.6 | 74.9 |

| 2010 | 79.9 | 80.4 | 83.5 | 76.3 |

| 2011 | 80.3 | 81.3 | 83.6 | 75.8 |

| 2012 | 80.2 | 80.3 | 86.3 | 76.8 |

| 2013 | 83.0 | 83.3 | 87.8 | 79.0 |

| 2014 | 83.8 | 85.3 | 85.9 | 78.9 |

Right Chart:

| Year | Poor | Low Income | Middle Income | High Income |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 67.7 | 65.8 | 71.3 | 76.8 |

| 2001 | 66.6 | 67.5 | 70.9 | 76.1 |

| 2002 | 69.1 | 68.1 | 71.3 | 78.0 |

| 2003 | 65.7 | 67.5 | 72.6 | 78.2 |

| 2004 | 68.1 | 68.5 | 73.5 | 79.1 |

| 2005 | 69.5 | 67.3 | 73.1 | 78.8 |

| 2006 | 69.0 | 68.3 | 72.4 | 79.1 |

| 2007 | 70.5 | 68.5 | 72.2 | 82.4 |

| 2008 | 75.1 | 68.8 | 75.1 | 82.8 |

| 2009 | 75.8 | 73.5 | 77.1 | 84.5 |

| 2010 | 77.9 | 75.4 | 79.4 | 85.8 |

| 2011 | 78.2 | 76.5 | 80.3 | 85.5 |

| 2012 | 78.9 | 77.9 | 77.6 | 86.3 |

| 2013 | 80.8 | 79.5 | 82.5 | 88.6 |

| 2014 | 81 | 80.5 | 83.2 | 89.5 |

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Health Interview Survey, 2000-2014.

Notes: White and Black are non-Hispanic. Hispanic includes all races.

- Trends:

- Overall, the percentage of children ages 0-17 years who had a well-child visit (as distinct from a symptom-driven visit) in the last 12 months increased from 71% in 2000 to 83.8% in 2014.

- From 2000 to 2014, the percentage of children who had a well-child visit increased significantly for Whites (71.3% to 85.3%), Blacks (75.4% to 85.9%), and Hispanics (65.3% to 78.9%).

- The percentage of children who had a well-child visit also increased for all income groups. From 2000 to 2014, the percentage of children with a well-child visit increased from 67.7% to 81.0% for poor families; from 65.8% to 80.5% for low-income families; rom 71.3% to 83.2% for middle-income families; and from 76.8% to 89.5% for high-income families.

- Groups With Disparities:

- In 2014, White children were more likely than Hispanic children to have had at least one well-child visit during the year (85.3% vs. 78.9%).

- In 2014, children in high-income families were more likely than children in poor, low-income, and middle-income families to have had at least one well-child visit during the year (89.5% vs. 81.0%, 80.5%, and 83.2%, respectively).

Slide 33

Prevention: Adolescent Meningitis Vaccine

- In 2010, children ages 10-14 years made up 6.7% of the U.S. population, and teens ages 15-19 made up 7.1%.10

- Youth ages 10-19 years are at risk of contracting meningitis, a possibly fatal11 infection.

- Meningococcal diseases are infections caused by the bacteria Neisseria meningitidis.12 Neisseria meningitides causes various infections but is most important as a potential cause of meningitis.12 It can also cause meningococcemia, a bloodstream infection.12

- The meningococcal vaccine can prevent most types of meningococcal disease.13 The meningococcal vaccine is recommended for all children ages 11-12 years. Effective January 2011, a second dose is recommended at age 16.13

Slide 34

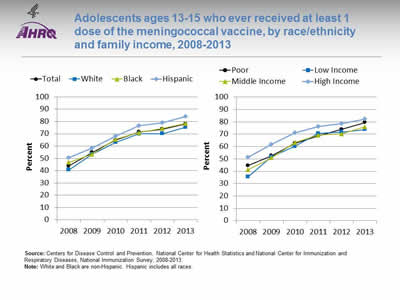

Adolescents ages 13-15 who ever received at least 1 dose of the meningococcal vaccine, by race/ethnicity and family income, 2008-2013

Image: Charts show adolescents ages 13-15 who ever received at least 1 dose of the meningococcal vaccine, by race/ethnicity and family income:

Left Chart:

| Race / Ethnicity | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 43.9 | 54.8 | 64.8 | 71.5 | 73.8 | 78.1 |

| Hispanic | 50.6 | 58.5 | 68.2 | 76.6 | 79.0 | 84.0 |

| Black | 46.7 | 53.4 | 65.5 | 71.0 | 74.3 | 78.4 |

| White | 40.7 | 53.4 | 63.0 | 69.9 | 70.1 | 75.3 |

Right Chart:

| Income | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poor | 44.7 | 52.6 | 62.6 | 68.5 | 74.0 | 79.5 |

| Low Income | 35.6 | 51.7 | 60.1 | 70.5 | 71.7 | 73.7 |

| Middle Income | 41.3 | 50.9 | 63.1 | 69.2 | 70.2 | 75.9 |

| High Income | 51.3 | 61.8 | 71.2 | 76.3 | 78.6 | 82.2 |

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics and National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, National Immunization Survey, 2008-2013.

Notes: White and Black are non-Hispanic. Hispanic includes all races.

- Overall: In 2013, the percentage of adolescents ages 13-15 who ever received at least 1 dose of the meningococcal vaccine was 78.1%.

- Trends: The percentage of adolescents ages 13-15 who ever received at least 1 dose of the meningococcal vaccine improved overall and for all racial/ethnic groups and income groups.

- Groups With Disparities:

- In 2013, the percentage of Hispanic adolescents (84%) ages 13-15 who ever received at least 1 dose of meningococcal vaccine was higher compared with White adolescents (75.3%).

- In all years, the percentage of adolescents ages 13-15 who ever received at least 1 dose of meningococcal vaccine was lower for those who live in poor, low-, and middle-income households compared with those from high-income households.

Slide 35

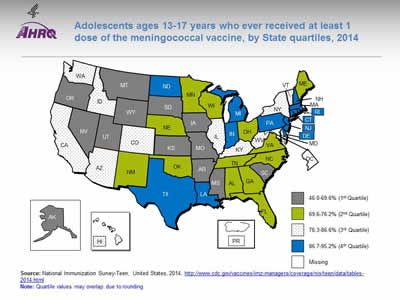

Adolescents ages 13-17 years who ever received at least 1 dose of the meningococcal vaccine, by State quartiles, 2014

Image: Map of the United States is color-coded by state to show estimated vaccination coverage with at least 1 dose of meningococcal vaccine among adolescents.

Source: National Immunization Survey-Teen, United States, 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/coverage/nis/teen/data/tables-2014.html

Notes: Quartile values may overlap due to rounding.

- Overall: This map shows estimated vaccination coverage with at least 1 dose of meningococcal vaccine among adolescents ages 13-17 years, by State. State values ranged from 46.0% (Mississippi) to 95.2% (Pennsylvania).

- Differences by State: Interquartile ranges follow:

- First quartile (lowest): 46.0%-69.6% (AK, AR, IA, KS, MO, MS, MT, NV, OR, SC, SD, UT, WY).

- Second quartile (second lowest): 69.6%-76.2% (AL, FL, GA ME, MN, NC, NE, NM, OH, OK, TN, VA, WI).

- Third quartile (second highest): 76.3%-86.6% (AZ, CA, CO, HI, ID, IL, KY, MD, NY, VT, WA, WV).

- Fourth quartile (highest): 86.7%-95.2% (CT, DE, IN, LA, MA, MI, ND, NH, NJ, PA, RI, TX).

Slide 36

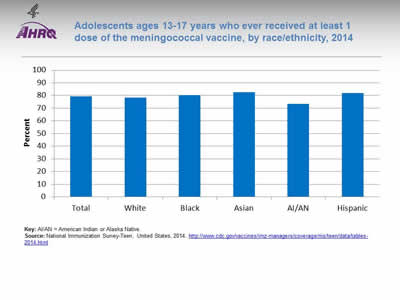

Adolescents ages 13-17 years who ever received at least 1 dose of the meningococcal vaccine, by race/ethnicity, 2014

Image: Chart shows adolescents ages 13-17 years who ever received at least 1 dose of the meningococcal vaccine, by race/ethnicity:

- Total - 79.3.

- White - 78.2.

- Black - 80.3.

- Asian - 82.5.

- AI/AN - 73.5.

- Hispanic - 82.1.

Key: AI/AN = American Indian or Alaska Native.

Source: National Immunization Survey-Teen, United States, 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/coverage/nis/teen/data/tables-2014.html

Notes:

- Overall Rate: In 2014, the estimated vaccination coverage for the meningitis vaccine among all adolescents ages 13-17 was 79.3%.

- Groups With Disparities:

- Hispanics (82.1%) and Asians (82.5%) had the highest coverage.

- American Indians and Alaska Natives (73.5%) had the lowest coverage.

Slide 37

Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Coverage for Adolescents

- Licensed HPV vaccine available since 2006.

- Recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) for routine vaccination of girls at age 11 or 12.14,15

- Quadrivalent HPV (HPV4) recommended by ACIP in 2011 for routine vaccination of boys at age 11 or 12.16

- Can be safely given with other routine vaccines; administration of all age-appropriate vaccines during a single visit recommended by ACIP.17

Slide 38

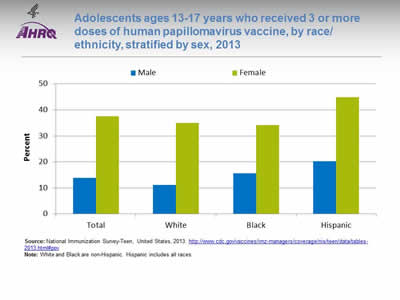

Adolescents ages 13-17 years who received 3 or more doses of human papillomavirus vaccine, by race/ethnicity, stratified by sex, 2013

Image: Chart shows adolescents ages 13-17 years who received 3 or more doses of human papillomavirus vaccine, by race/ethnicity, stratified by sex:

| Race / Ethnicity | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 13.9 | 37.6 |

| White | 11.1 | 34.9 |

| Black | 15.7 | 34.2 |

| Hispanic | 20.3 | 44.8 |

Source: National Immunization Survey-Teen, United States, 2013. http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/coverage/nis/teen/data/tables-2013.html#pov.

Notes: White and Black are non-Hispanic. Hispanic includes all races.

- Overall Rate: In 2013, 37.6% of adolescent females and 13.9% of adolescent males ages 13-17 years received 3 or more doses of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine.

- Groups With Disparities:

- Hispanic females ages 13-17 (44.8%) were more likely than both White (34.9%) and Black (34.2%) females ages 13-17 to have received 3 or more doses of the HPV vaccine. There were no statistically significant differences between White females and Black females.

- Both Black (15.7%) and Hispanic (20.3%) males ages 13-17 were more likely than White (11.1%) males ages 13-17 to have received 3 or more doses of the HPV vaccine. There were no statistically significant differences between White males and Black males.

Slide 39

Person-Centered Care

- Person-centered care has taken an important place in quality measurement and improvement in the United States and elsewhere.18-21

- Good communication and demonstrations of respect are two critical aspects of person-centered care.22,23

Slide 40

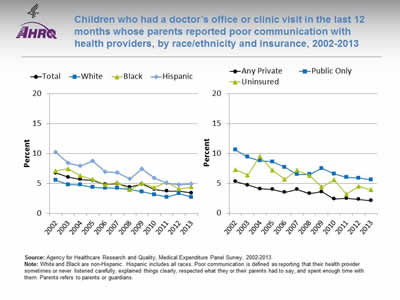

Children who had a doctor's office or clinic visit in the last 12 months whose parents reported poor communication with health providers, by race/ethnicity and insurance, 2002-2013

Image: Charts show children who had a doctor's office or clinic visit in the last 12 months whose parents reported poor communication with health providers, by race/ethnicity and insurance:

Left Chart:

| Race / Ethnicity | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 6.7 | 6.1 | 5.7 | 5.5 | 4.8 | 4.9 | 4.4 | 4.9 | 4.0 | 3.8 | 3.7 | 3.4 |

| White | 5.6 | 4.8 | 4.8 | 4.4 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 4.0 | 3.6 | 3.1 | 2.7 | 3.3 | 2.7 |

| Black | 7.1 | 7.5 | 6.3 | 5.7 | 4.8 | 5.1 | 4.0 | 5.1 | 4.3 | 5.2 | 4.1 | 4.4 |

| Hispanic | 10.2 | 8.4 | 7.9 | 8.8 | 7.0 | 6.8 | 5.8 | 7.4 | 5.9 | 5.1 | 4.8 | 4.9 |

Right Chart:

| Year | Any Private | Public Only | Uninsured |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 5.3 | 10.6 | 7.3 |

| 2003 | 4.7 | 9.4 | 6.4 |

| 2004 | 4.1 | 8.8 | 9.5 |

| 2005 | 4 | 8.6 | 7.2 |

| 2006 | 3.5 | 7.7 | 5.7 |

| 2007 | 4 | 6.5 | 7.2 |

| 2008 | 3.3 | 6.5 | 6.3 |

| 2009 | 3.6 | 7.5 | 4.4 |

| 2010 | 2.4 | 6.6 | 5.6 |

| 2011 | 2.5 | 6 | 3.2 |

| 2012 | 2.3 | 5.9 | 4.5 |

| 2013 | 2.1 | 5.6 | 3.9 |

Source: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2002-2013.

Notes: White and Black are non-Hispanic. Hispanic includes all races. Poor communication is defined as reporting that their health provider sometimes or never listened carefully, explained things clearly, respected what they or their parents had to say, and spent enough time with them. Parents refers to parents or guardians.

- Overall Rate: In 2013, 3.4% of parents reported poor communication with their children's health provider.

- Trends:

- From 2002 to 2013, the percentage of children whose parents reported poor communication with their health providers decreased from 6.7% to 3.4%.

- Between 2002 and 2013, the percentage of children whose parents reported poor communication decreased for all racial/ethnic and insurance groups.

- Groups With Disparities:

- In 2013, the percentage reporting poor communication with health providers was higher for Hispanic children (4.9%) and Black (4.4%) children compared with White children (2.7%).

- In 2013, 2.1% of parents of privately insured children reported poor communication compared with 5.6% of parents of publicly insured children.

Slide 41

Patient Safety: Birth Trauma

- Cases included in birth trauma measure:

- Hemorrhage below the scalp.

- Cerebral hemorrhage at birth.

- Spinal cord injury at birth.

- Facial nerve injury at birth.

- Bone injury not elsewhere classified at birth.

- Nerve injury not elsewhere classified at birth.

- Birth trauma not elsewhere classified.24

- Many of these injuries to neonates may be preventable.25

Slide 42

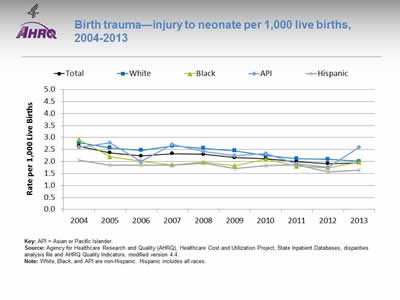

Birth trauma—injury to neonate per 1,000 live births, 2004-2013

Image: Chart shows birth trauma—injury to neonate per 1,000 live births:

| Year | Total | White | Black | API | Hispanic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 2.64 | 2.79 | 2.92 | 2.59 | 2.05 |

| 2005 | 2.36 | 2.57 | 2.20 | 2.79 | 1.85 |

| 2006 | 2.23 | 2.47 | 2.01 | 2.01 | 1.85 |

| 2007 | 2.33 | 2.65 | 1.86 | 2.71 | 1.84 |

| 2008 | 2.30 | 2.55 | 1.97 | 2.41 | 1.94 |

| 2009 | 2.16 | 2.45 | 1.82 | 2.24 | 1.70 |

| 2010 | 2.12 | 2.25 | 2.09 | 2.34 | 1.82 |

| 2011 | 2.00 | 2.12 | 1.80 | 1.89 | 1.87 |

| 2012 | 1.91 | 2.09 | 1.74 | 1.76 | 1.56 |

| 2013 | 1.93 | 2.00 | 1.97 | 2.60 | 1.64 |

Key: API = Asian or Pacific Islander.

Source: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, State Inpatient Databases, disparities analysis file and AHRQ Quality Indicators, modified version 4.4.

Notes: White, Black, and API are non-Hispanic. Hispanic includes all races.

- Overall Rate: In 2013, the birth trauma-neonatal injury rate was 1.9 per 1,000 live births.

- Trends:

- Birth trauma-neonatal injury rates fell from 2.6 per 1,000 live births in 2004 to 1.9 per 1,000 live births in 2013.

- Between 2004 and 2013, birth trauma-neonatal injury rates fell for all racial/ethnic groups, except for Asians and Pacific Islanders (APIs).

- Groups With Disparities:

- In 2013, Hispanic neonates (1.6 per 1,000 live births) were less likely to experience birth trauma compared with White neonates (2.0 per 1,000 live births).

Slide 43

Care Coordination Measures

- Children and adolescents whose health provider usually asks about prescription medications and treatments from other doctors.

- Emergency department (ED) visits with a principal diagnosis related to mental health, alcohol, or substance abuse.

- ED visits for asthma.

Slide 44

Communication About Prescription Medications and Treatments From Other Doctors

- Children are at risk for medication errors, including those due to polypharmacy, for various reasons26:

- Their size and physiologic variability.

- Limited communication ability and other factors.26

- Good medical practice includes asking patients about all their medications which can prevent adverse events.27

- The Food and Drug Administration and others urge patients to tell health care providers about all their medications.28

- Health care systems are trying strategies to better communicate with patients about medications other health care professionals give them.29

Slide 45

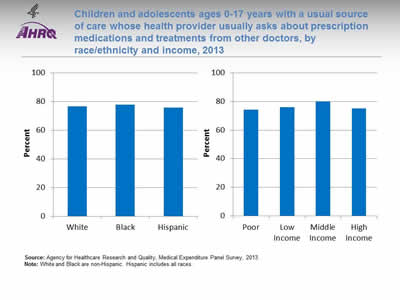

Children and adolescents ages 0-17 years with a usual source of care whose health provider usually asks about prescription medications and treatments from other doctors, by race/ethnicity and income, 2013

Image: Charts show children and adolescents with a usual source of care whose health provider usually asks about prescription medications and treatments from other doctors, by race/ethnicity and income:

Left Chart:

- White - 76.6.

- Black - 77.8.

- Hispanic - 75.9.

Right Chart:

- Poor - 74.3.

- Low Income - 76.1.

- Middle Income - 80.

- High Income - 75.2.

Source: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2013.

Notes: White and Black are non-Hispanic. Hispanic includes all races.

- Trends: From 2002 to 2013, the percentage of children and adolescents whose health provider usually asked about medications and treatments from other doctors increased significantly, from 71.1% to 76.6% (data not shown).

- Groups With Disparities:

- In 2013, there were no statistically significant differences between Whites (76.6%), Blacks (77.8%), and Hispanics (75.9%) in the percentage of children whose health provider asked about medications and treatments from other doctors.

- In 2013, there were no statistically significant differences by income:

- Poor, 74.3%.

- Low income, 76.1%.

- Middle income, 80.0%.

- High income, 75.2%.

Slide 46

Emergency Department Visits Related to Mental Health and Substance Abuse

- EDs are a common source of care for mental illness when high-quality mental health care is not available in the community.30

- Some ED use for mental health and substance abuse problems among young people is seen as preventable with appropriate ambulatory care.

- Mental, emotional, and behavioral health services are lacking for as many as 50% of children and adolescents with high needs.31

Slide 47

Emergency Department Visits Related to Mental Health and Substance Abuse

- EDs are often not staffed or equipped to provide optimal psychiatric care, leading to long wait times for appropriate care.32

- ED staff observing patients waiting for psychiatric care find it difficult to efficiently care for patients with other medical emergencies.33

- Efforts are underway to prevent avoidable ED use through strategies such as case management.34,35

Slide 48

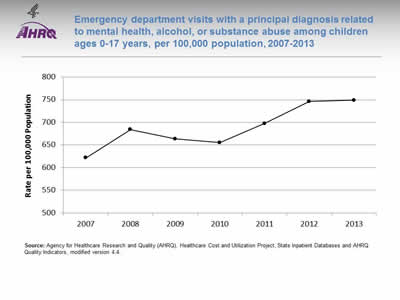

Emergency department visits with a principal diagnosis related to mental health, alcohol, or substance abuse among children ages 0-17 years, per 100,000 population, 2007-2013

Image: Chart shows emergency department visits with a principal diagnosis related to mental health, alcohol, or substance abuse among children ages 0-17 years:

| Year | Rate per 100,000 Population |

|---|---|

| 2007 | 621.8 |

| 2008 | 684 |

| 2009 | 663.3 |

| 2010 | 655.3 |

| 2011 | 697.5 |

| 2012 | 746 |

| 2013 | 749 |

Source: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, State Inpatient Databases and AHRQ Quality Indicators, modified version 4.4.

Notes:

- Overall Rate: In 2013, among children ages 0-17 years, there were 749 ED visits related to mental health, alcohol, or substance use per 100,000 population.

- Trends: ED visit rates for children related to mental health, alcohol, or substance use worsened between 2007 (621.8 per 100,000 population) and 2013 (749 per 100,000 population).

Slide 49

Emergency Department Visits for Asthma

- Asthma is a common chronic disease among children.36

- ED visits for asthma are often preventable if a child receives high-quality ambulatory care.

- Three strategies are most likely to improve provider adherence to guidelines for asthma care:

- Decision support tools.

- Feedback and audit.

- Clinical pharmacy support.37

Slide 50

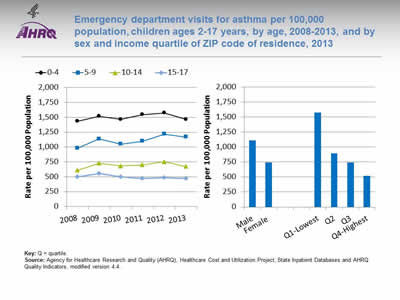

Emergency department visits for asthma per 100,000 population, children ages 2-17 years, by age, 2008-2013, and by sex and income quartile of ZIP code of residence, 2013

Image: Charts show emergency department visits for asthma per 100,000 population, children ages 2-17 years, by age, and by sex and income quartile of ZIP code of residence:

Left Chart:

| Year | 0-4 | 5-9 | 10-14 | 15-17 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 1432.9 | 978.4 | 609.7 | 496.8 |

| 2009 | 1517 | 1135.6 | 726.2 | 555.9 |

| 2010 | 1465.2 | 1050.1 | 681.4 | 497.7 |

| 2011 | 1545 | 1096.9 | 698.7 | 472.9 |

| 2012 | 1574.3 | 1218.3 | 752.9 | 483.6 |

| 2013 | 1464.4 | 1169.3 | 670 | 471 |

Right Chart:

- Male - 1110.7.

- Female 741.9.

- Q1-Lowest - 1568.7.

- Q2 - 889.8.

- Q3 - 743.8.

- Q4-Highest - 516.4.

Key: Q = quartile.

Source: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, State Inpatient Databases and AHRQ Quality Indicators, modified version 4.4.

Notes:

- Overall Rate: In 2013, the overall rate of ED visits for asthma was 930 per 100,000 (data not shown).

- Trend: From 2008 to 2013, the rate of ED visits for asthma worsened for children ages 5-9 (from 978 per 100,000 population to 1,169 per 100,000).

- Groups With Disparities:

- In 2013, male children ages 2-17 were 1.5 times as likely as female children to experience an ED visit for asthma (1,111 per 100,000 population vs. 742 per 100,000).

- In 2013, the rate of asthma ED visits was lower for children in the highest income quartile (516 per 100,000 population) compared with children in the first (1,569 per 100,000 population), second (890 per 100,000 population), and third quartiles (744 per 100,000 population).

Slide 51

References

- Cassedy A, Fairbrother G, Newacheck P. The impact of insurance instability on children's access, utilization, and satisfaction with health care. Ambul Pediatr 2008 Sep-Oct;8(5):321-8. PMID: 18922506. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1530156708001172. Accessed March 22, 2016.

- Guevara J, Moon J, Hines E, et al. Continuity of public insurance coverage: a systematic review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev 2014;71(2):115-37. PMID: 24227811. http://mcr.sagepub.com/content/71/2/115.long. Accessed March 22, 2016.

- Kenney G, Pelletier J. Monitoring duration of coverage in Medicaid and CHIP to assess program performance and quality. Acad Pediatr 2011;May-Jun;11(3 Suppl):S34-41. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1876285910001257. Accessed March 22, 2016.

- Children's Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2009. Public Law 111-3. http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-111publ3/html/PLAW-111publ3.htm. Accessed May 15, 2015.

- Harrington M, Kenney GM, et al. 2014. CHIPRA mandated evaluation of the Children's Health Insurance Program: final findings. Report submitted to the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Ann Arbor, MI: Mathematica Policy Research; August 2014. http://www.medicaid.gov/chip/downloads/chip_report_congress-2014.pdf (1.032 MB). Accessed March 22, 2016.

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Visual Impairment in Children Ages 1-5: Screening. January 2011. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Topic/recommendation-summary/visual-impairment-in-children-ages-1-5-screening. Accessed March 22, 2016.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Recommendations for Preventive Pediatric Health Care. http://pediatriccare.solutions.aap.org/DocumentLibrary/Periodicity%20Schedule_FINAL.pdf (394.89 KB) Last updated 2014. Accessed March 22, 2016.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Preventive Care for Children. 26 Covered Preventive Services for Children.

- Adolescent Health. AH-1. Increase the proportion of adolescents who have had a wellness checkup in the past 12 months. http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/Adolescent-Health. Accessed March 22, 2016.

Slide 52

References

- U.S. Census Bureau. Community facts: 2010 profile of general population and housing characteristics: 2010 demographic profile data. http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=DEC_10_DP_DPDP1. Accessed March 22, 2016.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Meningitis. http://www.cdc.gov/meningitis/index.html. Accessed March 22, 2016.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Meningococcal Disease. http://www.cdc.gov/meningococcal/index.html. Accessed March 22, 2016.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Meningococcal VIS. http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/vis/vis-statements/mening.html. Accessed 05/18/2015.

- Markowitz LE, Dunne EF, Saraiya M, et al. Quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR 2007;56(RR02). http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5602a1.htm. Accessed March 22, 2016.

- FDA licensure of bivalent human papillomavirus vaccine (HPV2, Cervarix) for use in females and updated HPV vaccination recommendations from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR 2010 May 28;59(20):626-9. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5920a4.htm. Accessed March 22, 2016.

- Recommendations on the use of quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine in males—Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2011. MMWR 2011 Dec 23;60(50):1705-8. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6050a3.htm?s_cid=mm6050a3_w. Accessed March 22, 2016.

- Kroger AT, Sumaya CV, Pickering LK, et al. General recommendations on immunization: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR 2011;60(RR02). http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr6002a1.htm?s_cid=rr6002a1_w. Accessed March 22, 2016.

- Iedema R, Angell B. What are patients' care experience priorities? BMJ Qual Saf 2015 Jun;24 (6):356-9. PMID: 25972222. http://qualitysafety.bmj.com/content/24/6/356.long. Accessed March 22, 2016.

- Basch E. New frontiers in patient-reported outcomes: adverse event reporting, comparative effectiveness, and quality assessment. Annu Rev Med 2014;65:307-17. PMID: 24274179. http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev-med-010713-141500?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3Dpubmed&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&journalCode=med. Accessed March 22, 2016.

Slide 53

References

- American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Hospital Care and Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. Patient- and family-centered care and the pediatrician's role. Pediatrics 2012 Feb;129(2):394-404. Epub 2012 Jan 30. PMID: 22291118. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/129/2/394.long. Accessed March 22, 2016.

- Bethell C. Engaging families (and ourselves) in quality improvement: an optimistic and developmental perspective. Acad Pediatr 2013 Nov-Dec;13(6 Suppl):S9-11. PMID: 24268092. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S187628591300212X. Accessed March 22, 2016.

- Dudley N. Ackerman A, Brown KM, et al. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Pediatric Emergency Medicine; American College of Emergency Physicians Pediatric Emergency Medicine Committee; Emergency Nurses Association Pediatric Committee. Patient- and family-centered care of children in the emergency department. Pediatrics 2015 Jan;135(1):e255-72. PMID: 25548335. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/135/1/e255.long. Accessed March 22, 2016.

- Phillips-Salimi C, Haase J, Kooken W. Connectedness in the context of patient-provider relationships: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs 2012 Jan;68(1):230-45. Epub 2011 Jul 20. PMID: 21771040. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3601779/. Accessed March 22, 2016.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Birth Trauma Rate—Injury to Neonate: Technical Specifications. AHRQ Quality Indicators™, Version 5.0. Patient Safety Indicators 17. http://www.qualityindicators.ahrq.gov/Downloads/Modules/PSI/V50/TechSpecs/PSI_17_Birth%20Trauma%20RateInjury%20to%20Neonate.pdf (61.38 KB) Last update November 2014. Accessed March 22, 2016.

- Ramphul M, Kennelly MM, Burke G, et al. Risk factors and morbidity associated with suboptimal instrument placement at instrumental delivery: observational study nested within the Instrumental Delivery & Ultrasound randomised controlled trial ISRCTN 72230496. BJOG 2015 Mar;122(4):558-63. Epub 2014 Nov 21. PMID: 25414081. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1471-0528.13186/full. Accessed March 22, 2016.

- Neuspiel D, Taylor M. Reducing the risk of harm from medication errors in children. Health Serv Insights 2013 Jun 30;6:47-59. PMID: 25114560. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4089677/. Accessed March 22, 2016.

- General Medical Council. Prescribing guidance: sharing information with colleagues. 2015. http://www.gmc-uk.org/guidance/ethical_guidance/14320.asp. Accessed March 22, 2016.

Slide 54

References

- Food and Drug Administration. Strategies to Reduce Medication Errors: Working to Improve Medication Safety. 2013. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/ResourcesForYou/Consumers/ucm143553.htm. Accessed March 22, 2016.

- Sarzynski EM, Luz CC, Rios-Bedoya CF, et al. Considerations for using the "brown bag" strategy to reconcile medications during routine outpatient office visits. Qual Prim Care 2014;22(4):177-87. PMID: 25695529.

- Alakeson V, Frank T. Health care reform and mental health care delivery. Psychiatr Serv 2010 Nov;61(11):1063. PMID: 21041340. http://ps.psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/ps.2010.61.11.1063. Accessed March 22, 2016.

- Simon AE, Pastor PN, Reuben CA, et al. Use of mental health services by children ages six to 11 with emotional or behavioral difficulties. Psychiatr Serv 2015 May 15:appips201400342. [Epub ahead of print]. PMID: 25975889.

- Institute of Medicine. Committee on the Future of Emergency Care in the United States Health System. Hospital-based emergency care: at the breaking point. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2007.

- Alakeson V, Pande N, Ludwig M. A plan to reduce emergency room "boarding" of psychiatric patients. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010 Sep;29(9):1637-42. PMID: 20820019. http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/29/9/1637.long. Accessed March 22, 2016.

- Kirk T, Di Leo P, Rehmer P, et al. A case and care management program to reduce use of acute care by clients with substance use disorders. Psychiatr Serv 2013 May;64(5):491-3. PMID: 23632578. http://ps.psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/appi.ps.201200258. Accessed March 22, 2016.

- Olmstead T, Cohen J, Petry N. Health-care service utilization in substance abusers receiving contingency management and standard care treatments. Addiction 2012;107(8):1462-70. Epub 2012 Apr 17. PMID: 22296262. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3634865/. Accessed March 22, 2016.

- Akinbami LJ, Moorman JE, Simon AE, et al. Trends in racial disparities for asthma outcomes among children 0-17 years, 2001-2010. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014 Sep;134(3):547-53. Epub 2014 Aug 1. PMID: 25091437. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0091674914007982#. Accessed March 22, 2016.

- Okelo S, Butz AM, Sharma R, et al. Interventions to modify health care provider adherence to asthma guidelines: a systematic review. Pediatrics 2013 Sep;132(3):517-34. Epub 2013 Aug 26. PMID: 23979092. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4079294/. Accessed March 22, 2016.

Slide 55

Chartbook on Healthy Living

Lifestyle Modification

Slide 56

Lifestyle Modification and Health

- Unhealthy behaviors place many Americans at risk for a variety of diseases.

- Lifestyle practices account for more than 40% of the differences in health among individuals.1

Slide 57

Impact of Behaviors on Health

- A recent study2 examined the effects of three healthy lifestyles on the risks of all-cause mortality and developing chronic conditions among adults in the United States:

- Not smoking.

- Engaging in at least 150 minutes of moderate or vigorous physical activity per week.

- Eating a healthy diet (e.g., grains, fruits, vegetables).

Slide 58

Impact of Behaviors on Health

- Compared with adults who did not engage in healthy behaviors, the risk for all-cause mortality was reduced by:

- 56% among nonsmokers.

- 47% among adults who were physically active.

- 26% among adults who consumed a healthy diet.2

- The risk of death decreased as the number of healthy behaviors increased. For adults engaged in all three healthy behaviors, the risk of death was reduced by:

- 82% for all causes.

- 65% for cardiovascular disease.

- 83% for cancer.

- 90% for other causes.2

Slide 59

Lifestyle Modification Measures

- Adult current smokers with a checkup in the last 12 months who received advice to quit smoking.

- Adults with obesity who ever received advice from a health professional to exercise more.

- Adults with obesity who did not spend half an hour or more in moderate or vigorous physical activity at least five times a week.

Slide 60

Lifestyle Modification Measures

- Children ages 2-17 for whom a health provider gave advice about exercise.

- Adults with obesity who ever received advice from a health professional about eating fewer high-fat or high-cholesterol foods.

- Children ages 2-17 for whom a health provider gave advice within the past 2 years about healthy eating.

Slide 61

Prevention: Counseling To Quit Smoking

- Smoking harms nearly every bodily organ and causes or worsens many diseases.

- In the past 50 years, more than 20 million premature deaths have been attributable to smoking and exposure to secondhand smoke.3

- Smoking causes more than 87% of deaths from lung cancer and more than 79% of deaths from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.3

Slide 62

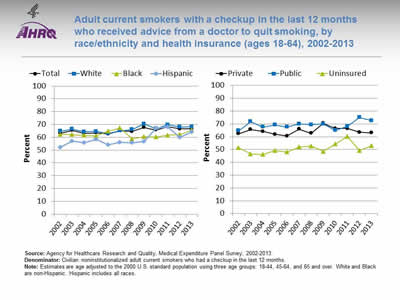

Adult current smokers with a checkup in the last 12 months who received advice from a doctor to quit smoking, by race/ethnicity and health insurance (ages 18-64), 2002-2013

Image: Charts show adult current smokers with a checkup in the last 12 months who received advice from a doctor to quit smoking, by race/ethnicity and health insurance:

Left Chart:

| Race / Ethnicity | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 63.1 | 65.3 | 63.1 | 63.4 | 62.7 | 65.1 | 64.5 | 67.6 | 65.7 | 68.2 | 66.5 | 66.5 |

| White | 64.8 | 66.4 | 64.2 | 64.6 | 63.0 | 65.0 | 66.1 | 70.5 | 66.7 | 69.8 | 67.9 | 68.1 |

| Black | 62.3 | 62.2 | 61.5 | 61.0 | 64.8 | 67.3 | 58.7 | 60.5 | 60.1 | 61.7 | 62.1 | 65.8 |

| Hispanic | 52.0 | 57.2 | 55.7 | 58.5 | 54.2 | 56.1 | 55.6 | 56.6 | 67.1 | 68.1 | 59.9 | 64.2 |

Right Chart:

| Insurance | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Private | 62.3 | 65.7 | 64.1 | 61.9 | 60.7 | 65.9 | 62.8 | 70.5 | 66.4 | 66.4 | 63.4 | 63.1 |

| Public | 64.7 | 71.7 | 67.6 | 69.1 | 67.6 | 70.1 | 69.3 | 69.9 | 65.0 | 68.1 | 75.0 | 72.6 |

| Uninsured | 51.3 | 46.6 | 46.2 | 49.2 | 48.1 | 52.0 | 52.8 | 48.5 | 54.2 | 60.3 | 49.2 | 52.9 |

Source: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2002-2013.

Denominator: Civilian noninstitutionalized adult current smokers who had a checkup in the last 12 months.

Notes: Estimates are age adjusted to the 2000 U.S. standard population using three age groups: 18-44, 45-64, and 65 and over. White and Black are non-Hispanic. Hispanic includes all races.

- Importance: Smoking is a modifiable risk factor, and health care providers can help encourage patients to change their behavior and quit smoking. The 2008 update of the Public Health Service Clinical Practice Guideline Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence concludes that counseling and medication are both effective tools alone, but the combination of the two methods is more effective in increasing smoking cessation. For more information, visit http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/clinicians-providers/guidelines-recommendations/tobacco/index.html.

- Overall Rate: In 2013, the percentage of adult current smokers with a checkup in the last 12 months who received advice from a doctor to quit smoking was 66.5%.

- Trends:

- From 2002 to 2013, the percentage of adult current smokers with a checkup in the last 12 months who received advice from a doctor to quit smoking increased overall (from 63.1% to 66.5%), for Hispanics (from 52.0% to 64.2%), and for Whites (from 64.8% to 68.1%).

- Groups With Disparities:

- In 2013, among adult current smokers ages 18-64 with a checkup, those with public health insurance (72.6%) were more likely than those with private health insurance (63.1%) to receive advice from a doctor to quit smoking.

- In 2013, among adult current smokers ages 18-64 with a checkup, those who were uninsured (52.9%) were less likely than those with private insurance (63.1%) to receive advice from a doctor to quit smoking.

- In all years except 2011, uninsured adult current smokers ages 18-64 with a checkup were less likely to receive advice to quit smoking compared with those with private insurance.

- From 2002 to 2013, there was no statistically significant change in the disparity between uninsured and privately insured adult current smokers with a checkup in the last 12 months who received advice from a doctor to quit smoking.

Slide 63

Prevention: Counseling for Adults About Exercise

- About one-third of adults (34.9%) are obese:

- Obesity-related conditions are among the leading causes of preventable death, such as heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, and some cancers.4

- Physicians encounter many high-risk individuals, whom they can educate about personal risks and lifestyle changes that can help reduce weight and increase activity.5

Slide 64

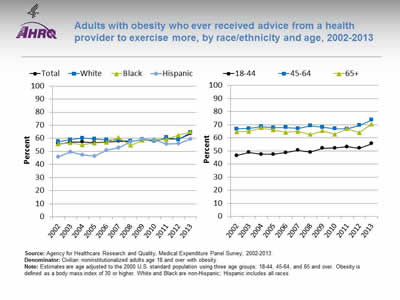

Adults with obesity who ever received advice from a health provider to exercise more, by race/ethnicity and age, 2002-2013

Image: Charts show adults with obesity who ever received advice from a health provider to exercise more, by race/ethnicity and age:

Left Chart:

| Race / Ethnicity | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 55.6 | 57.0 | 57.2 | 56.7 | 57.1 | 57.9 | 57.4 | 59.1 | 58.4 | 59.6 | 59.3 | 63.5 |

| White | 57.5 | 59.0 | 60.1 | 59.7 | 58.8 | 58.7 | 57.8 | 59.1 | 57.8 | 60.7 | 58.9 | 64.5 |

| Black | 55.8 | 56.6 | 55.1 | 56.3 | 56.8 | 60.8 | 54.7 | 58.5 | 59.1 | 59.2 | 62.4 | 64.8 |

| Hispanic | 45.9 | 49.7 | 47.4 | 46.5 | 50.8 | 52.8 | 57.2 | 59.4 | 58.8 | 55.7 | 55.9 | 59.5 |

Right Chart:

| Year | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18-44 | 46.5 | 48.8 | 47.4 | 47.4 | 48.7 | 50.4 | 49.0 | 52.0 | 52.1 | 53.1 | 52 | 55.5 |

| 45-64 | 66.8 | 67.1 | 68.6 | 67.8 | 68.0 | 67.1 | 69.2 | 68.0 | 67.0 | 66.8 | 69.5 | 73.7 |

| 65+ | 64.6 | 64.9 | 67.6 | 66.0 | 64.3 | 64.9 | 62.6 | 65.5 | 62.7 | 66.9 | 64 | 70.6 |

Source: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2002-2013.

Denominator: Civilian noninstitutionalized adults age 18 and over with obesity.

Notes: Estimates are age adjusted to the 2000 U.S. standard population using three age groups: 18-44, 45-64, and 65 and over. Obesity is defined as a body mass index of 30 or higher. White and Black are non-Hispanic; Hispanic includes all races.

- Importance: Physician-based exercise and diet counseling is an important component of effective weight loss interventions. Such interventions have been shown to increase levels of physical activity among sedentary patients, resulting in a sustained favorable body weight and body composition.5

- Overall Rate: In 2013, the overall percentage of adults with obesity who had ever received advice from a health provider to exercise more was 63.5%.

- Trends:

- From 2002 to 2013, the percentage of obese adults who ever received advice from a health provider to exercise more increased overall (from 55.6% to 63.5%), for Hispanics (from 45.9% to 59.5%), and for Blacks (from 55.8% to 64.8%).

- From 2002 to 2013, the percentage of obese adults who ever received advice from a health provider to exercise more increased for those ages 18-44 (from 46.5% to 55.5%).

- Groups With Disparities:

- In 2013, obese Hispanic adults (59.5%) were less likely than White obese adults (64.5%) to ever receive advice from a health provider to exercise more.

- In 8 of 12 years, obese Hispanic adults were less likely than White obese adults to ever receive advice from a health provider to exercise more.

- From 2002 to 2013, the disparity between Hispanic and White obese adults who ever received advice from a doctor to exercise more grew smaller but was still present.

- In 2013, obese adults ages 45-64 (73.7%) and age 65 and over (70.6%) were more likely than those ages 18-44 (55.5%) to ever receive advice from a doctor to exercise more.

- In all years, obese adults ages 45-64 and age 65 and over were more likely than those ages 18-44 to ever receive advice from a doctor to exercise more.

Slide 65

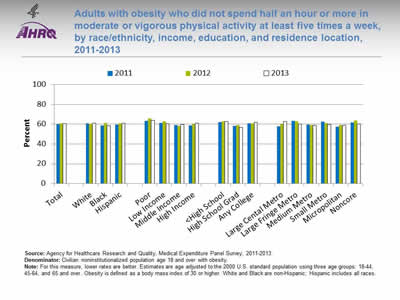

Adults with obesity who did not spend half an hour or more in moderate or vigorous physical activity at least five times a week, by race/ethnicity, income, education, and residence location, 2011-2013

Image: Chart shows adults with obesity who did not spend half an hour or more in moderate or vigorous physical activity at least five times a week, by race/ethnicity, income, education, and residence location:

| Characteristics | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 60.1 | 60.7 | 60.5 |

| White | 60.6 | 60.4 | 61.1 |

| Black | 58.9 | 61.3 | 58.3 |

| Hispanic | 59.6 | 60.6 | 61.2 |

| Poor | 63.5 | 66.0 | 64.0 |

| Low Income | 61.4 | 62.8 | 60.5 |

| Middle Income | 59.3 | 58.5 | 59.7 |

| High Income | 58.5 | 59.7 | 60.9 |

| <High School | 62.0 | 62.9 | 62.5 |

| High School Grad | 58.1 | 59.0 | 56.9 |

| Any College | 60.6 | 60.8 | 61.7 |

| Large Cental Metro | 57.9 | 60.1 | 62.8 |

| Large Fringe Metro | 63.3 | 63.0 | 60.2 |

| Medium Metro | 59.5 | 59.1 | 58.9 |

| Small Metro | 62.4 | 61.1 | 59.9 |

| Micropolitan | 57.3 | 59.1 | 58.9 |

| Noncore | 61.5 | 63.7 | 60.1 |

Source: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2011-2013.

Denominator: Civilian noninstitutionalized population age 18 and over with obesity.

Notes: For this measure, lower rates are better. Estimates are age adjusted to the 2000 U.S. standard population using three age groups: 18-44, 45-64, and 65 and over. Obesity is defined as a body mass index of 30 or higher. White and Black are non-Hispanic; Hispanic includes all races.

- Importance: The 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans recommend that adults engage in at least 2 hours and 30 minutes a week of moderate-intensity physical activity or 1 hour and 15 minutes a week of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity, or an equivalent combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity aerobic activity. For more information, visit http://health.gov/paguidelines/guidelines/.

- Overall Rate: In 2013, the overall percentage of adults with obesity who did not spend half an hour or more in moderate or vigorous physical activity at least five times a week was 60.5%.

- Groups With Disparities:

- In 2013, there were no statistically significant differences by race/ethnicity, income, education, or residence location in the percentage of adults with obesity who did not spend half an hour or more in moderate or vigorous physical activity at least five times a week.

Slide 66

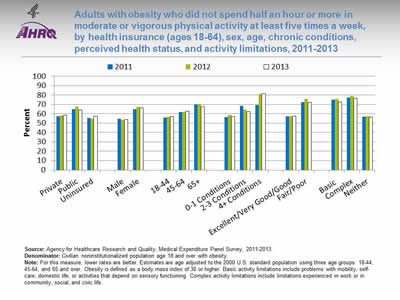

Adults with obesity who did not spend half an hour or more in moderate or vigorous physical activity at least five times a week, by health insurance (ages 18-64), sex, age, chronic conditions, perceived health status, and activity limitations, 2011-2013

Image: Chart shows adults with obesity who did not spend half an hour or more in moderate or vigorous physical activity at least five times a week, by health insurance, sex, age, chronic conditions, perceived health status, and activity limitations:

| Characteristics | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Private | 57.3 | 58.1 | 58.4 |

| Public | 65.0 | 67.3 | 64.2 |

| Uninsured | 55.4 | 54.9 | 57.6 |

| Male | 54.8 | 53.5 | 54.0 |

| Female | 65.1 | 67.5 | 66.5 |

| 18-44 | 56.0 | 56.9 | 56.9 |

| 45-64 | 61.7 | 62.3 | 62.7 |

| 65+ | 69.8 | 69.7 | 67.6 |

| 0-1 Conditions | 56.5 | 58.5 | 57.0 |

| 2-3 Conditions | 68.5 | 64.5 | 62.5 |

| 4+ Conditions | 69.1 | 81.5 | 81.5 |

| Excellent / Very Good / Good | 57.1 | 57.1 | 57.6 |

| Fair / Poor | 72.6 | 75.9 | 72.1 |

| Basic | 75.1 | 75.9 | 72.6 |

| Complex | 77.3 | 78.9 | 76.8 |

| Neither | 56.9 | 57.1 | 56.6 |

Source: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2011-2013.

Denominator: Civilian noninstitutionalized population age 18 and over with obesity.

Notes: For this measure, lower rates are better. Estimates are age adjusted to the 2000 U.S. standard population using three age groups: 18-44, 45-64, and 65 and over. Obesity is defined as a body mass index of 30 or higher. Basic activity limitations include problems with mobility, self-care, domestic life, or activities that depend on sensory functioning. Complex activity limitations include limitations experienced in work or in community, social, and civic life.

- Groups With Disparities:

- In 2013, there were no statistically significant differences by health insurance in the percentage of obese adults ages 18-64 who did not spend half an hour or more in moderate or vigorous physical activity at least five times a week.

- In 2011 and 2012, adults ages 18-64 with obesity with only public insurance were less likely to spend half an hour or more in vigorous physical activity at least five times a week compared with those with private insurance.

- In 2013, the percentage of adults with obesity who did not spend half an hour or more in moderate or vigorous physical activity at least five times a week was higher for:

- Females (66.5%) compared with males (54.0%).

- Those ages 45-64 (62.7%) and age 65 and over (67.6%) compared with those ages 18-44 (56.9%).

- Those with 4 or more chronic conditions (81.5%) compared with those with 0-1 chronic conditions (57.0%).

- Those who perceived their health status to be fair or poor (72.1%) compared with those who perceived their health status to be excellent, very good, or good (57.6%).

- Those with basic (72.6%) or complex activity limitations (76.8%) compared with those with neither limitation (56.6%).

Slide 67

Prevention: Counseling About Exercise for Children and Adolescents

- About 17% of children and adolescents ages 2-19 are overweight or obese.6

- Childhood is when people can establish healthy lifelong habits, and physicians can play an important role in encouraging healthy behaviors.

- The 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans recommend that children and adolescents engage in 1 hour or more of physical activity everyday.

Note:

- For more information, visit www.health.gov/paguidelines/guidelines/default.aspx.

Slide 68

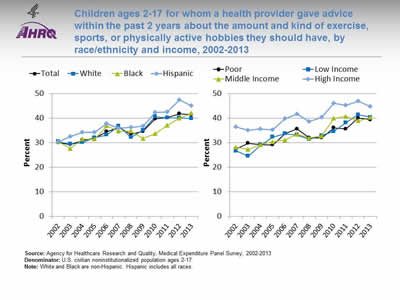

Children ages 2-17 for whom a health provider gave advice within the past 2 years about the amount and kind of exercise, sports, or physically active hobbies they should have, by race/ethnicity and income, 2002-2013

Image: Charts show children ages 2-17 for whom a health provider gave advice within the past 2 years about the amount and kind of exercise, sports, or physically active hobbies they should have, by race/ethnicity and income:

Left Chart:

| Race / Ethnicity | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 |

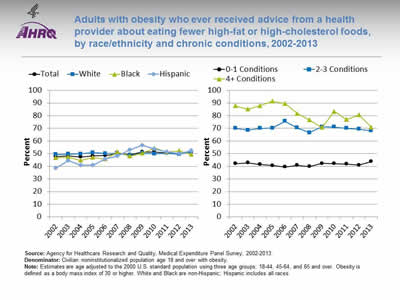

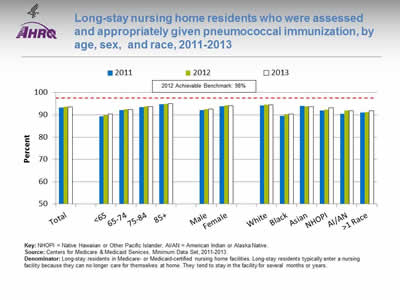

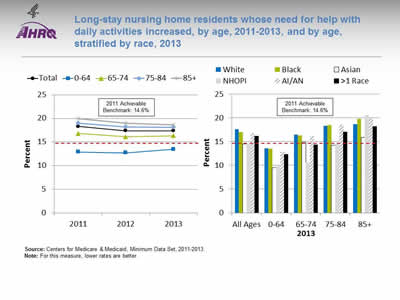

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|