Start Planning Your Evaluation As Early As You Can

Develop the evaluation approach before the pilot begins.

Careful and timely planning will go a long way toward producing useful results, for several reasons. First, you may want to collect pre-intervention data and understand the decisions that shaped the choice of the intervention and the selection of practices for participation. Second, you may want to capture early experiences with implementing the intervention to understand any challenges and refinements made. Finally, you may want to suggest minor adaptations to the intervention's implementation to enhance the evaluation's rigor. For example, if an organization wanted to implement a PCMH model in five practices at a time, the evaluator might suggest randomly picking the five practices from those that meet eligibility criteria. This would make it possible to compare any changes in care delivery and outcomes of the intervention practices to changes in a control group of eligible practices that will adopt the PCMH model later. If the project had selected the practices before consulting with the evaluator, the evaluation might have to rely on less rigorous non-experimental methods.

Consider the Purpose and Audience for the Evaluation

Who is the audience for the evaluation?

What questions do they want answered?

Identifying stakeholders who will be interested in the evaluation's results, the decisions that your evaluation is expected to inform, and the type of evidence required is crucial to determining what questions to ask and how to approach the evaluation. For example, insurers might focus on the intervention's effects on the total medical costs they paid and on patient satisfaction; employers might be concerned with absentee rates and workforce productivity; primary care providers might focus on practice revenue and profit, quality of care, and staff satisfaction; and labor unions might focus on patient functioning, satisfaction, and out-of-pocket costs. Potential adverse effects of the intervention and the reporting burden from the evaluation should be considered as well.

Consider, too, the form and rigor of the evidence the stakeholders need. Perspectives differ on how you should respond to requests for information from funders or other stakeholders when methodological issues mean you cannot be confident in the findings. We recommend deciding during the planning stage how to approach and reconcile trade-offs between rigor and relevance. Sometimes the drawbacks of a possible evaluation—or certain evaluation components—are serious enough (for example, if small sample size and resulting statistical power issues will render cost data virtually meaningless) that resources should not be used to generate information that is likely to be misleading.

Questions to ask include: Do the stakeholders need numbers or narratives, or a combination? Do stakeholders want ongoing feedback to refine the model as it unfolds, an assessment of effectiveness at the end of the intervention, or both? Do the results need only to be suggestive of positive effects, or must they rigorously demonstrate robust impacts for stakeholders to act upon them? How large must the effects be to justify the cost of the intervention? Thinking through these issues will help you choose the outcomes to measure, data collection approach, and analytic methods.

Understand the Challenges of Evaluating Primary Care Interventions

Some of the challenges to evaluating primary care interventions include (see also the bottom box of Figure 1):

- Time and intensity needed to transform care. It takes time for practices to transform, and for those transformations to alter outcomes.1 Many studies suggest it will take a minimum of 2 or 3 years for motivated practices to really transform care.2,3,4,5,6 If the intervention is short or it is not substantial, it will be difficult to show changes in outcomes. In addition, a short or minor intervention may only generate small effects on outcomes, which are hard to detect.

- Power to detect impacts when clustering exists. Even with a long, intensive intervention, clustering of outcomes at the practice levela may make it difficult for your evaluation to detect anything but very large effects without a large number of practices. For example, some studies spend a lot of time and resources collecting and analyzing data on the cost effects of the PCMH model. However, because of clustering, an intervention with too few practices might have to generate cost reductions of more than 70 percent for the evaluation to be confident that observed changes are statistically significant.7 As a result, if an evaluation finds that the estimated effects on costs are not statistically significant, it's not clear whether the intervention was ineffective or the evaluation had low statistical power (see Appendix A for a description of how to calculate statistical power in evaluations).

- Data collection. Obtaining accurate, complete, and timely data can be a challenge. If multiple payers participate in the intervention, they may not be able to share data; if no payers are involved, the evaluator may be unable to obtain data on service use and expenditures outside the primary care practice.

- Generalizability. If the practices that participate are not typical, the results may not be generalizable to other practices.

- Measuring the counterfactual. It is difficult to know what would have occurred in the intervention practices in the absence of the intervention (the "counterfactual"). Changing trends over time make it hard to ascribe changes to the intervention without identifying an appropriate comparison group, which can be challenging. In addition, multiple interventions may occur simultaneously or the comparison group may undertake changes similar to those found in the intervention, which can complicate the evaluation.

Adjust Your Expectations So They Are Realistic, and Match the Evaluation to Your Resources

The goal of your evaluation is to generate the highest quality information possible within the limits of your resources. Given the challenges of evaluating a primary care intervention, it is better to attempt to answer a narrow set of questions well than to study a broad set of questions but not provide definitive or valid answers to any of them. As described above, you need adequate resources for the intervention and evaluation to make an impact evaluation worthwhile.

With limited resources, it is often better to scale back the evaluation. For example, an evaluation that focuses on understanding and improving the implementation of an intervention can identify early steps along the pathway to lowering costs and improving health care. We recommend using targeted interviews to understand the experiences of patients, clinicians, staff, and other stakeholders, and measuring just a few intermediate process measures, such as changes in workflows and the use of health information technology. Uncovering any challenges encountered with these early steps can allow for refinement of the intervention before trying out a larger-scale effort.

The evaluator and implementers should work together to describe the theory of change. The logic model will guide what to measure, and when to do so.

Describe the logic model, or theory of change, showing why and how the intervention might improve outcomes of interest. In this step, the evaluators and implementers work together to describe each component of the intervention, the pathways through which they could affect outcomes of interest, and the types of effects expected in the coming months and years. Because primary care interventions take place in the context of the internal practice and the external health care environments, the logic model should identify factors that might affect outcomes—either directly or indirectly—by affecting implementation of the intervention. Consider all factors, even if you may not be able to collect data on all of them, and you may not have enough practices to control for each factor in regression analyses to estimate impacts. Practice- or organization-specific factors include, for example, patient demographics and language, size of patient panels, practice ownership, and number and type of clinicians and staff. Other examples of practice- specific factors include practice leadership and teamwork.8 Factors describing the larger health care environment include practice patterns of other providers, such as specialists and hospitals, community resources, and payment approaches of payers. Intervention components should include the aspects of the intervention that vary across the practices in your study, such as the type and amount of services delivered to provide patient-centered, comprehensive, coordinated, accessible care, with a systematic focus on quality and safety. They may also include measures capturing variation across intervention practices in the offer and receipt of: technical assistance to help practices transform; additional payments to providers and practices; and regular feedback on selected patient outcomes, such as health care utilization, quality, and cost metrics.

Find resources on logic models and tools to conduct implementation and impact studies in the Resource Collection.

A logic model serves several purposes (see Petersen, Taylor, and Peikes9 for an illustration and references). It can help implementers recognize gaps in the logic of transformation early so they can take appropriate steps to modify the intervention to ensure success. As an evaluator, you can use the logic model approach to determine at the outset whether the intervention has a strong underlying logic and a reasonable chance of improving outcomes, and what effect sizes the intervention might need to produce to be likely to yield statistically significant results. In addition, the logic model will help you decide what to measure at different points in time to show whether the intervention was implemented as intended, improved outcomes, and created unintended outcomes, and identify any facilitators and barriers to implementation. However, while the logic model is important, you should remain open to unexpected information, too. Finally, the logic model's depiction of how the intervention is intended to work can be useful in helping you interpret findings. For example, if the intervention targets more assistance to practices that are struggling, the findings may show a correlation between more assistance and worse outcomes. Understanding the specifics of the intervention approach will prevent you from mistakenly interpreting such a finding as indicating that technical assistance worsens outcomes.

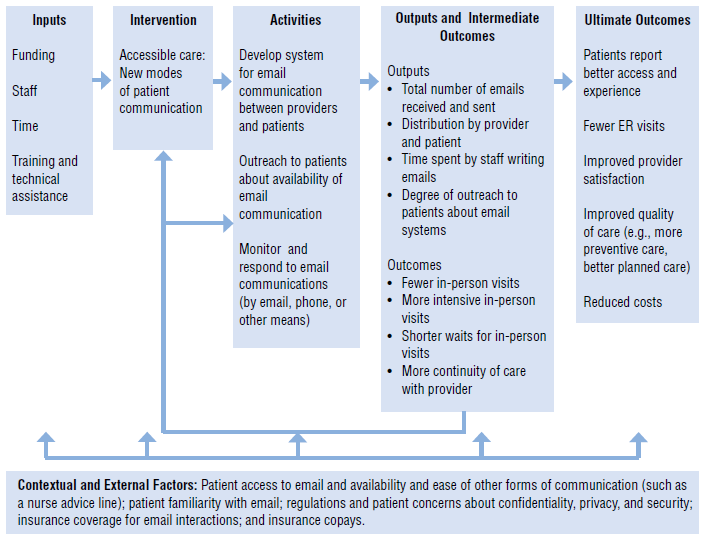

As an example of this process, consider a description of the pathway linking implementation to outcomes for expanded access, one of the features the medical home model requires. Improved access is intended to improve continuity of care with the patient's provider and reduce use of the emergency room (ER) and other sites of care. If the intervention you are evaluating tests this approach, you could consider how the medical home practices will expand access. Will the practices use extended hours, email and telephone interactions, or have a nurse or physician on call after hours? How will the practices inform patients of the new options and any details about how to use them? Because nearly all interventions are adapted locally during implementation, and many are not implemented fully, the logic model should specify process indicators to document how the practices implemented the approach. For practices that use email interactions to increase access, some process indicators could include how many patients were notified about the option by mail or during a visit, the overall number of emails sent to and from different practice staff, the number and distribution by provider and per patient, and time spent by practice staff initiating and responding to emails (Figure 2). You could assess which process indicators are easiest to collect, depending on the available data systems and the feasibility of setting up new ones. To decide which measures to collect, consider those likely to reflect critical activities that must occur to reach intended outcomes, and balance this with an understanding of the resources needed to collect the data and the impact on patient care and provider workflow.

Figure 2. Logic Model of a PCMH Strategy Related to Email Communication

Source: Adapted from Petersen, Taylor, and Peikes. Logic Models: The Foundation to Implement, Study, and Refine Patient-Centered Medical Home Models, 2013, Figure 2.9

Expected changes in intermediate outcomes from enhanced email communications might include the following:

- Fewer but more intensive in-person visits as patients resolve straightforward issues via email

- Shorter waits for appointments for in-person visits

- More continuity of care with the same provider, as patients do not feel the need to obtain visits with other providers when they cannot schedule an in-person visit with their preferred provider

Ultimate outcomes might include:

- Patients reporting better access and experience

- Fewer ER visits as providers can more quickly intervene when patients experience problems

- Improved provider experience, as they can provide better quality care and more in-depth in-person visits

- Lower costs to payers from improved continuity, access, and quality

You should also track unintended outcomes that program designers did not intend but might occur. For example, using email could reduce practice revenue if insurers do not reimburse for the interactions and fewer patients come for in-person visits. Alternatively, increased use of email could lead to medical errors if the absence of an in-person visit leads the clinician to miss some key information, or could lead to staff burnout if it means staff spend more total time interacting with patients.

Some contextual factors that might influence the ability of email interactions to affect intended and unintended outcomes include: whether patients have access to and use email and insurers reimburse for the interactions; regulations and patient concerns about confidentiality, privacy, and security; and patient copays for using the ER.

What outcomes are you interested in tracking? The following resources are a good starting point for developing your own questions and outcomes to track:

- The Commonwealth Fund’s PCMH Evaluators Collaborative provides a list of core outcome measures.

- The Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS®) PCMH survey instrument developed by AHRQ provides patient experience measures.