Establishing a Program of In Situ Simulations: Facilitator Guide

AHRQ Safety Program for Perinatal Care

Slide 1: Establishing a Program of In Situ Simulations

Say:

Establishing a Program of In Situ Simulations is a pillar of the AHRQ Safety Program for Perinatal Care. This module introduces in situ simulation and discusses the use of in situ simulation on labor and delivery or L&D units.

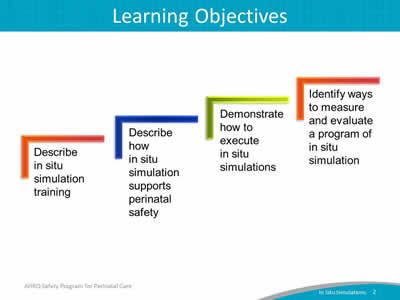

Slide 2: Learning Objectives

Say:

This presentation will—

- Describe in situ simulation training.

- Describe how in situ simulation supports perinatal safety.

- Demonstrate how to execute in situ simulations.

- Identify ways to measure and evaluate a program of in situ simulation.

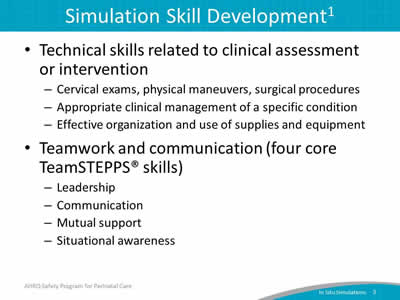

Slide 3: Simulation Skill Development

Say:

Simulation can be used for individual and team training with respect to two distinct but complementary skills.

The first set of skills is clinical skills. Dedicated simulation centers often focus on these types of skills, such as cervical exam assessments, physical maneuvers for managing a shoulder dystocia, or cord prolapse, and even surgical procedural skills. Simulation can also be used to train staff on the appropriate clinical management of specific conditions, or on the effective organization and use of supplies and equipment.

Simulation can also be used to practice teamwork and communication skills. These types of skills include the four core TeamSTEPPS® skills: leadership, communication techniques (such as SBAR or Situation/Background/Assessment/ Recommendation), mutual support, and situational awareness.

These teamwork skills are useful for regular, day-to-day care of labor and delivery patients, but are especially critical for use during rapid response to urgent maternity care conditions, and when applying unit-established protocols or checklists to focus the clinical response to the specific perinatal situations.

Slide 4: In Situ Simulation Defined

Say:

In situ simulations are physically integrated into the usual clinical environment, allowing for practice in one’s own hospital setting with familiar resources and equipment. In situ is Latin for "in its original place."

Each person involved performs his or her own role as if the simulation scenario were real. All involved disciplines participate, including typical support personnel such as lab or pharmacy staff.

In situ simulation excels at helping to improve teamwork and communication skills, thus complementing the technical/clinical simulation training that staff might receive in a dedicated simulation center.

Slide 5: Benefits of In Situ Simulation

Say:

In situ simulation training offers many practical benefits:

- It provides a method to improve reliability and safety in high-risk areas such as L&D.

- It allows for experiential learning related to teamwork and communication that fosters a culture of patient safety.

- It improves the unit’s ability to address latent threats and systematic issues that might not otherwise be identified during simulation within a dedicated simulation center.

Slide 6: Evidence for Using Simulations in L&D

Say:

Multiple studies have demonstrated that teamwork training using simulation as an independent intervention results in improvement in knowledge, practical skills, communication, and team performance in acute maternity care situations.

Slide 7: Scenarios for Simulation

Say:

In situ simulations can be designed to replay real events that have occurred on a unit.

They can be used to simulate uncommon, but serious, obstetric emergencies requiring rapid recognition, response, and teamwork. These emergencies could include shoulder dystocia, postpartum hemorrhage, cord prolapse, or eclamptic seizures.

Simulation scenarios can also be designed to train staff on or fine-tune new processes and protocols—for example, the use of safe cesarean section checklist in the L&D operating room.

Slide 8: Three Components of an In Situ Simulation

Say:

The three components of an in situ simulation are briefing, facilitating the simulation, and debriefing. Each component will be discussed in detail on subsequent slides.

Slide 9: Briefing

Say:

The first part of an in situ simulation is the briefing. The briefing usually takes about 10 minutes.

The participants are asked to treat the simulated event like an actual patient situation.

The facilitator should emphasize that the focus of the simulation is on how teams communicate and perform as a unit, not on evaluating individual staff clinical acumen or procedural skills. The facilitator can clarify a policy question from participants if raised, but if an individual needs remedial help for a clinical/technical error it is best to talk to that person individually and privately after the debriefing to avoid embarrassment in front of peers.

The facilitator should share information about the timeframe for the simulation, use of simulation equipment (if applicable), and rules of participation during the briefing.

Slide 10: Briefing: Using Video

Say:

Consider the use of video recording in situ simulations when they are conducted. Video recording can be a useful tool for reviewing team performance during the debriefing.

However, video recording can induce anxiety in participants. If used, the facilitator should explain the purpose of video recording to participants prior to simulation.

If the recording will be used solely for debriefing the simulation with participants, assure participants that the video will be destroyed at the end of the training. If the video recording might be used for education of others later, seek legal guidance and obtain signed release documentation from participants.

Slide 11: Facilitating the Simulation: Scenario Design

Say:

A well-designed simulation scenario has a clinical context appropriate for eliciting team behaviors of interest. Not all contexts are equal for training purposes, particularly when it comes to training for technical/procedural skills versus training for teamwork and communication.

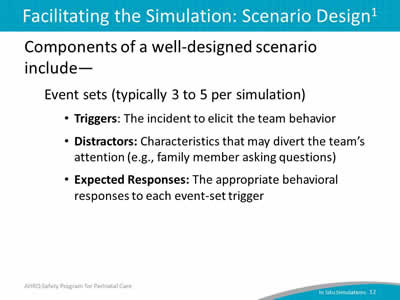

Slide 12: Facilitating the Simulation: Scenario Design

Say:

A well-built scenario generally consists of three to five event sets. Event sets can be created by breaking a clinical situation into chunks. For example, in a scenario, one event set may have to do with the identification of an issue needing activation of a rapid response from clinical staff, another event set might have to do with selecting and applying clinical treatments to respond to an unfolding emergency, and a third event set might have to do with transitioning a patient from one care venue to the other, such as L&D to the operating room or intensive care unit. Having multiple event sets within a scenario helps create a realistic idea of what it is like to work in that unit, creates reliability, and provides more than one opportunity for teams to practice teamwork behaviors.

Each event set usually has one trigger. A trigger is a finding or piece of information designed to elicit a team behavior. Each trigger is associated with an expected response. For example, a staff person that identifies a patient deteriorating rapidly calls for help and uses SBAR to communicate the problem as help arrives. In addition to a trigger and expected response, an event set often contains a distractor, which is a characteristic of the situation that may divert the team’s attention, such as an anxious family member asking questions.

Slide 13: Facilitating the Simulation: Execution

Say:

One way to think about the execution of an in situ simulation is that it should be conducted more like an improvisation than as a scripted play. The facilitator’s primary role is one of observation. The facilitator provides key information to help the simulation move along, but not in a tightly scripted way.

A simulation that is too complex will overwhelm learners—most people can only integrate a few key learning points from a scenario. And, scripting the scenario too closely makes it difficult to observe targeted response behaviors.

Slide 14: Facilitating the Simulation: Execution

Say:

The facilitator should keep the simulation going for a prespecified time, usually 15 to 20 minutes. Simulations structured to lead to “one right answer” are not realistic and won’t help teams develop the ability to recognize and adapt to changing circumstances.

For example, in a scenario designed to evaluate team performance in response to worsening preeclampsia and ultimately seizure, the trigger event, a tonic-clonic seizure should be allowed to continue for a prespecified amount of time, for example, 5 to 6 minutes, even if the team provides a correct technical response (for example intravenous bolus of magnesium) within the first couple of minutes. It is during these periods of the simulation that teamwork and communication behaviors, such as SBAR, use of huddles, and closed-loop communication can be evaluated.

Slide 15: Debriefing: Definition

Say:

Debriefing helps participants understand the complex team skills and knowledge required for quality patient care. Team members share their perspectives on what occurred during the scenario and reach common ground.

The debrief can help the in situ simulation learning process in several important ways. The debrief provides a structure for understanding the scenario and helps ensure that everyone will take away similar lessons from the experience. Finally, debriefing helps to keep the discussion focused on events relevant to the learning objectives.

Note: though the terms used are the same, and the principle is similar, debriefing in the context of a simulation is somewhat different from the debriefing teamwork technique used by TeamSTEPPS.

Slide 16: Debriefing: Logistics

Say:

Plan to use about 3 to 5 minutes to debrief for every minute of the actual simulation. So, a simulation run for 15 minutes will need at least 45 minutes to debrief. This does not include time needed to review video if the simulation is being recorded.

Consider reserving a separate meeting space for the debrief, especially if a screen to review a video recording of the simulation is needed.

Slide 17: Debriefing: Introduce the Debrief Process

Say:

The debrief process usually involves four steps: introducing the process, describing what happened, conducting an analysis of team performance, and identifying lessons learned. Each of these steps will be discussed on the next several slides.

The facilitator should emphasize several points when introducing the debrief process.

First, all team members who participated in the simulation are expected to participate in the debriefing session.

Second, the facilitator should remind participants that the focus is primarily on team performance, with a secondary focus on clinical/technical performance. Probe with questions like these:

- Did you maintain your situational awareness?

- Did you hear closed-loop communication when the order for prescription was given?

Note that, although teamwork and communication skills are emphasized during the debriefing session, clinical or technical errors should not be overlooked. The debrief can be used to clarify quick clinical/technical issues, but individual remediation should be addressed outside of the debrief.

Consider a dual debrief, in which a portion of the debrief focuses on teamwork and communication, and a separate portion focuses on the clinical/technical response. Probe with these questions:

- Did you perceive the team had a shared mental model?

- Was standardized language such as SBAR used?

Slide 18: Debriefing: Describe What Happened

Say:

The next step in the debrief process is to describe what happened. As a suggestion, the facilitator might first have every participant state their name, role, and what went well for them during the simulation.

If the team recorded the simulation, watch the video. Pause the video at various intervals to discuss the following questions:

- What went well?

- What could have gone better?

- What would you want to do differently next time?

Slide 19: Debriefing: Describe What Happened

Say:

It is important for the facilitator to empathize to the participants that it is "their debriefing."

In discussing why things happened in the scenario as they did, the team should focus on critical aspects of teamwork and communication.

Video review is extremely helpful in allowing the participants to see exactly what communication occurred and what kind of teamwork was employed. Ideally everyone participates in the debriefing so that their unique perspective (such as their role) is heard.

Slide 20: Debriefing: Conduct a Performance Analysis

Say:

Consider using simulation assessment tools, such as a form or a checklist. A simulation assessment tool can be used in a variety of ways. They can be used by any observers of a simulation to make notes. They can also be used as a guide for the facilitator to reference during the debriefing. If the simulation was video-recorded, participants can use it to evaluate themselves as they watch the video. The team’s performance can be compared with expected responses:

- Were the expected behaviors performed when necessary?

- If so, were they performed correctly or could they be improved?

Slide 21: Debriefing: Identify Lessons Learned

Say:

The final step in the debriefing process is to identify lessons learned and look ahead to how the team can generalize what they learned in the scenario to their daily practice.

The team discusses what behaviors they may begin performing. Explicit measures associated with the simulation scenario can help promote reflection about how to transfer what went well in the simulation to the actual clinical environment.

Slide 22: Planning

Say:

In the next section, several aspects of planning to establish a unitwide program of in situ simulation will be discussed.

Slide 23: Engage Leadership

Say:

First, L&D leadership and unit staff should discuss and determine a shared vision for simulation training. A shared vision will help obtain support for the program and avoid concern about interference with patient care. In addition, it will help alleviate concerns from staff about the purpose of simulation. In coming up with a shared vision, your team might—

- Be clear about the purpose of simulations--teamwork development as opposed to individual performance evaluation.

- Identify concrete training goals.

Slide 24: Staff Readiness

Say:

Additional planning steps include ensuring that unit staff have completed teamwork and communication training (e.g., TeamSTEPPS) before starting simulations. This training provides the team with a common language and communication framework to use during simulations.

It is also important to have enough staff who can facilitate in situ simulations. A facilitator does not necessarily have to be an expert in all the technical aspects of the simulation, but rather can introduce the scenario, introduce new information as needed, and observe the simulation unfold. Most important, this person can facilitate the team debriefing following the simulation.

Slide 25: Participants

Say:

All disciplines and staff involved in providing services or care to patients on L&D units should participate in simulations. This might include the following:

- Maternity care providers (obstetricians/physicians/midwives).

- Nursing staff.

- Neonatal providers.

- Anesthesiology staff.

- Residents (all specialties that provide care on labor and delivery).

- Operating room technicians/assistants.

- Administrative support personnel (unit clerks).

- Lab and pharmacy staff.

Slide 26: Participants

Say:

It is important to define clear requirements for staff participation. Which staff members are required to participate and how often? How many different scenarios should staff participate in, and will it vary by type of staff? Will incentives or consequences be used to drive staff participation? These are all considerations for establishing participant expectations in the unit’s program of in situ simulation.

Slide 27: Simulation Scenarios

Say:

Another consideration is the selection of simulation scenarios to use for conducting simulations. Nine sample scenarios for in situ simulation are available as part of the Safety Program for Perinatal Care. These include scenarios for—

- Postpartum hemorrhage.

- Shoulder dystocia.

- Umbilical cord prolapse.

- Uterine tachysystole.

- Antepartum hemorrhage.

- Preeclampsia /seizure.

- Severe abdominal pain/vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC).

- Postoperative cesarean section complication.

- Magnesium toxicity.

Each scenario focuses on teamwork and communication skills and includes a simulation assessment tool.

Slide 28: Simulation Scenarios

Say:

These scenarios are samples, and units can modify them to meet unit and team needs. Units can also consider developing their own scenarios, or use scenarios that are available through professional organizations, perinatal quality and safety organizations, and commercial entities.

A video on in situ simulation that was developed as part of the AHRQ Safety Program for Perinatal Care is in two locations:

Slide 29: Equipment

Say:

Simulation scenarios can also be adapted to fit the resources available within a hospital or unit.

In most cases, in situ simulations generally use the equipment of the clinical area in which the simulation takes place.

A pelvic model or childbirth simulator may be required for some of the scenarios that require the use of specific physical maneuvers (e.g., shoulder dystocia).

In the tool developed to accompany this slide presentation, a list of resources for pelvic models and simulators is provided.

Although not an absolute requirement, the use of standardized patients—that is, actors trained to play the part of the patient or family member—may replace simluators in many cases. In general, standardized patients who participate in a simulation also participate in the debriefing to provide a patient/caregiver perspective on the events that occurred.

Slide 30: Logistics

Say:

Scheduling staff and ensuring needed equipment is available for simulation is a critical logistical aspect of establishing a program of in situ simulation.

Create a schedule for simulation trainings that aligns with the unit’s shared vision and staff participation criteria.

Plan for transporting simulation equipment to and from the unit. If possible, store equipment in the L&D unit where the simulations will take place. If not, set aside time for transport, setup, and dismantling.

It can be helpful to assign one or two staff members the specific role of setting up before and cleaning up after each simulation.

Slide 31: Logistics

Say:

Most in situ simulation should use the equipment available in the course of routine care. However, pelvic models and “props” may be needed to substitute for patients to simulate physical maneuvers. Setting standards around the use of real or simulated medical supplies and equipment is important.

The use of real supplies such as medications or blood products, adds authenticity to a simulation but may be considered wasteful, particularly in the setting of supply or medication or blood shortages.

An alternative to using real supplies is to set aside supplies to be used only for simulation training. This approach requires vigilance to ensure that simulated medications, blood products, or other equipment don’t mistakenly get into circulation and get used on actual patients. Be sure to follow all local infection-control policies and practices for reusing simulation equipment.

Slide 32: Conflicts With Patient Care

Say:

Because in situ simulation takes place on the unit, using unit resources, including L&D rooms and supplies, conflicts between conducting simulations and providing patient care will arise.

Clinicians may voice concern about delaying actual patient care in order to conduct an in situ simulation. For unit staff buy-in, consider prospectively designating standards and limits for conducting simulations on the unit based on volume and acuity of patient care needs, and available staffing. Scheduled simulations can be canceled or ended early because of competing patient care demands, or time limits imposed on simulations to reduce impact on clinical care.

Slide 33: Conflicts With Patient Care

Say:

Consider discussing this issue with your hospital’s patient advocacy groups, if possible. When the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center sought input from its family advocate group about the impact of simulation on delays in patient care, the group expressed support for simulations because the benefits of simulation training outweighed the disadvantages.

Slide 34: Evaluation

Say:

The last section of this presentation discusses the evaluation of an established program of in situ simulation.

Slide 35: Data for Evaluation

Say:

A successful in situ simulation training program requires evaluation and continuous improvement.

- Consider using data from safety culture surveys to evaluate impact.

- Conduct brief simulation participant experience surveys.

- Collect qualitative feedback from staff participants who have participated in simulations.

- Develop or use other measures to track the impact of simulation program.

Slide 36: Designing Measures: Clarify Purpose

Say:

In designing measures to evaluate a simulation program, it is important to clarify the purpose of measurement.

One purpose may be to diagnose root causes of performance deficiencies. Measures would be used to identify specific weaknesses, such as poor use of SBAR, or delays in contacting other service providers for assistance.

Another purpose may be to provide feedback and relay information regarding strengths and weaknesses as a remediation plan.

The purpose also may be to assess and evaluate the level of proficiency or readiness.

Slide 37: Designing Measures: What To Measure

Say:

After defining the purpose of evaluation, decide what to measure.

Outcomes are sometimes referred to as measures of effectiveness. They provide an indication of the extent to which the outcome of the task was successful.

A variety of outcomes can be assessed, such as the following:

- Accuracy—which measures the precision of performance (e.g., correct diagnosis, appropriate treatment).

- Timeliness—which measures how long it took for something to happen (e.g., time to incision).

- Productivity—which measures how much (e.g., patient volume in L&D).

- Efficiency—which measures the ratio of resources required versus used (e.g., OR supplies).

Slide 38: Designing Measures: What To Measure

Say:

Process measures that address issues of performance may also be important to evaluate. They can explain how and why certain outcomes may have happened "Was the decision made right (correctly)?" versus "Was the right decision made?"

This information is important when diagnosing root causes of performance deficiencies and providing feedback or follow-on training.

The following are some types of process:

- Procedural: Task work.

- Nonprocedural: Task work.

- Teamwork.

Slide 39: Unit Next Steps

Say:

Here are next steps a unit can take to begin establishing a program of in situ simulation:

- Obtain support from leadership for establishing a program of in situ simulation training.

- Build the foundation needed for simulation with TeamSTEPPS teamwork training.

- Develop participation criteria, choose scenarios, plan logistics, and secure equipment.

- Pilot-test program on a small-scale prior to widespread unit implementation.

Slide 40: References

Slide 41: References

Slide 42: Disclaimer