Chartbook on Women's Health Care: Slide Presentation

2014 National Healthcare Quality & Disparities Report

Contents

Introduction

Summary Tables

Access to Health Care

Patient Safety

Person-and Family-Centered Care

Communication and Care Coordination

Effective Treatment of Leading Causes of Morbidity and Mortality

Healthy Living

Affordability

References

Introduction

Slide 1

National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report

Chartbook on Women's Health Care

September 2015

Slide 2

Organization of the Chartbook on Women's Health Care

- Part of a series related to the National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report (QDR).

- Contents:

- Overview of the QDR.

- Overview of women, one of the priority populations of the QDR.

- Summary of trends in health care quality and disparities for females.

- Tracking of access and quality measures for females:

- Access to Health Care.

- Patient Safety.

- Person- and Family-Centered Care.

- Communication and Care Coordination.

- Effective Treatment of Leading Causes of Morbidity and Mortality.

- Healthy Living.

- Affordability.

Slide 3

National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report

- Annual report to Congress mandated in the Healthcare Research and Quality Act of 1999 (P.L. 106-129).

- Provides a comprehensive overview of:

- Quality of health care received by the general U.S. population.

- Disparities in care experienced by different racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups.

- Assesses the performance of our health system and identifies areas of strengths and weaknesses along three main axes:

- Access to health care.

- Quality of health care.

- Priorities of the National Quality Strategy.

Slide 4

National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report

- Based on more than 250 measures of quality and disparities covering a broad array of health care services and settings.

- Data generally available through 2012.

- Produced with the help of an Interagency Work Group led by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and submitted on behalf of the Secretary of Health and Human Services.

Slide 5

Changes for 2014

- New National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report (QDR):

- Integrates findings on health care quality and health care disparities into a single document to highlight the importance of examining quality and disparities together.

- Focuses on summarizing information on more than 200 measures that are tracked.

Slide 6

Key Findings of the 2014 QDR

- The Nation has made clear progress in improving the health care delivery system to achieve the three National Quality Strategy (NQS) aims: better care, smarter spending, and healthier people.

- There is still more work to do, specifically to address disparities in care.

- Access improved.

- Quality improved for most National Quality Strategy priorities.

- Few disparities were eliminated.

- Many challenges in improving quality and reducing disparities remain.

Slide 7

2014 Chartbooks

- 2014 QDR supported by a series of related chartbooks that:

- Present information on individual measures.

- Are updated annually.

- Are posted on the Web (http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/2014chartbooks/).

- Order and topics of chartbooks:

- Access to care.

- Priorities of the National Quality Strategy.

- Access and quality of care for different priority populations.

Slide 8

Six Chartbooks Organized Around Priorities of the National Quality Strategy

- Making care safer by reducing harm caused in the delivery of care.

- Ensuring that each person and family is engaged as partners in their care.

- Promoting effective communication and coordination of care.

- Promoting the most effective prevention and treatment practices for the leading causes of mortality, starting with cardiovascular disease.

- Working with communities to promote wide use of best practices to enable healthy living.

- Making quality care more affordable for individuals, families, employers, and governments by developing and spreading new health care delivery models.

Slide 9

Other Chartbooks Organized Around AHRQ's Priority Populations

- AHRQ's priority populations, specified in the Healthcare Research and Quality Act of 1999 (Public Law 106-129):

- Racial and ethnic minority groups.

- Low-income groups.

- Women.

- Children (under age 18).

- Older adults (age 65 and over).

- Residents of rural areas.

- Individuals with special health care needs, including:

- Individuals with disabilities.

- Individuals who need chronic care or end-of-life care.

Slide 10

Chartbook on Women's Health Care

- This chartbook includes:

- Summary of trends in health care quality and disparities for females.

- Figures illustrating select measures of Access to Health Care and 6 NQS Priorities for females.

- Introduction and Methods section of the 2014 National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report contains information about methods used in the chartbook.

- Appendixes include information about measures and data.

- A Data Query tool (http://nhqrnet.ahrq.gov/inhqrdr/data/query) provides access to all data tables.

Slide 11

Data Presented in This Chartbook

- Women age 18 years and over.

- One adolescent female measure related to human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine receipt.

- Breakouts by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status when available and compared with men.

- Further designations derived from special populations who receive care from the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) Community Health Centers.

Slide 12

Use of Health Care Services by Women

- Women, on average, use more health care services compared with men:

- More health care contacts and opportunities to receive counseling and preventive care.

- Women differ in disease risk factors and certain patterns of illness compared with men even when maternity care is excluded or considered separately (AHRQ HCUP; Women's Health USA, 2013).

Slide 13

Chronic Disease in Women

- Evidence demonstrates that chronic disease affects women and men differently:

- Related to biologic, socioeconomic, and cultural dynamics.

- Women experience a higher burden of chronic disease and tend to live more years with a disability compared with men (AHRQ HCUP; Women's Health USA, 2013).

Summary Tables

Slide 14

Chartbook on Women's Health Care

Summary Tables

Slide 15

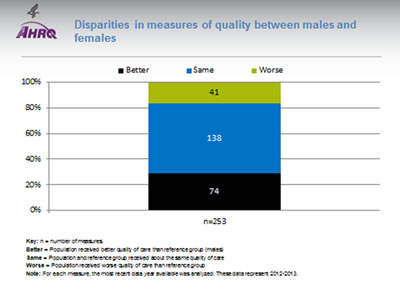

Disparities in measures of quality between males and females

Image: Chart shows disparities in measures of quality between males and females: Better - 74. Same - 138. Worse - 41. n = 253.

Key: n = number of measures.

Better = Population received better quality of care than reference group (males)

Same = Population and reference group received about the same quality of care

Worse = Population received worse quality of care than reference group

Note: For each measure, the most recent data year available was analyzed. These data represent 2012-2013.

- Females received better quality of care than males for 29% (74 of 253) of the measures.

- Females received worse quality of care than males for 16% (41 of 253) of the measures.

- There were no statistically significant differences between males and females for 55% (138 of 253) of the measures.

Slide 16

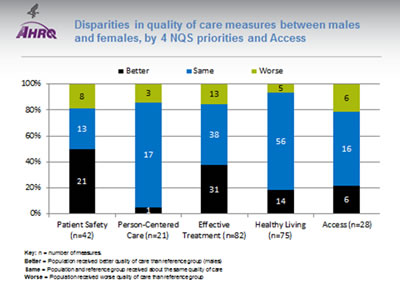

Disparities in quality of care measures between males and females, by 4 NQS priorities and Access

Image: Chart shows disparities in quality of care measures between males and females by NQS priorities. Patient Safety (n=42): Worse - 8; Same - 13; Better - 21. Person-Centered Care (n=21): Worse - 3; Same - 17; Better - 1. Effective Treatment (n=82): Worse - 13; Same - 38; Better - 31. Healthy Living (n=75): Worse - 5; Same - 56; Better - 14. Access (n=28): Worse - 6; Same - 16; Better - 6.

Key: n = number of measures.

Better = Population received better quality of care than reference group (males)

Same = Population and reference group received about the same quality of care

Worse = Population received worse quality of care than reference group

- Overall: Females received better care than males for Patient Safety (50%) and Effective Treatment (38%) measures.

- Patient Safety measures: Females received better care than males for 50% of the measures, the same for 31%, and worse for 19%.

- Person-Centered Care measures: Females received better care than males for 5% of the measures, the same for 81%, and worse for 14%.

- Effective Treatment measures: Females received better care than males for 38% of the measures, the same for 46%, and worse for 16%.

- Healthy Living measures: Females received better care than males for 19% of the measures, the same for 75%, and worse for 6%.

- Access measures: Females received better care than males for 21% of the measures, the same for 58%, and worse for 21%.

- There are insufficient numbers of reliable measures of Care Coordination and Care Affordability to summarize in this way.

Slide 17

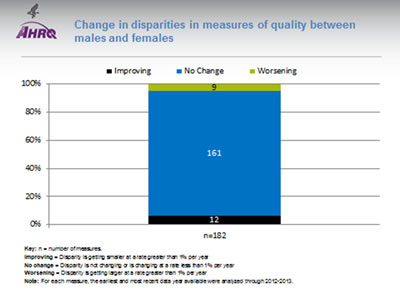

Change in disparities in measures of quality between males and females

Image: Chart shows change in disparities in measures of quality between males and females. Improving - 12. No Change - 161. Worsening - 9. n = 182.

Key: n = number of measures.

Improving = Disparity is getting smaller at a rate greater than 1% per year

No change = Disparity is not changing or is changing at a rate less than 1% per year

Worsening = Disparity is getting larger at a rate greater than 1% per year

Note: For each measure, the earliest and most recent data year available were analyzed through 2012-2013.

- Disparities between males and females were improving (getting smaller) for 7% (12 of 182) of the measures.

- Disparities between males and females were worsening (getting larger) for 5% (9 of 182) of the measures.

- Disparities between males and females were not changing for 88% (161 of 182) of the measures.

Slide 18

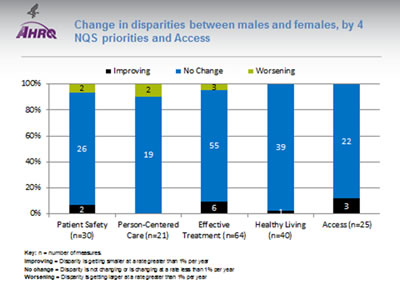

Change in disparities between males and females, by 4 NQS priorities and Access

Image: Chart shows change in disparities between males and females by NQS priorities. Patient Safety (n=30): Worsening - 2; No Change - 26; Improving - 2; Person-Centered Care (n=21): Worsening - 2; No Change - 19. Effective Treatment (n=64): Worsening - 3; No Change - 55; Improving - 6. Healthy Living (n=40): No Change - 39; Improving - 1. Access (n=25): No Change - 22; Improving - 3.

Key: n = number of measures.

Improving = Disparity is getting smaller at a rate greater than 1% per year

No change = Disparity is not changing or is changing at a rate less than 1% per year

Worsening = Disparity is getting larger at a rate greater than 1% per year

- Overall: There were no statistically significant changes in disparities between males and females for nearly 90% of the measures.

- Patient Safety measures: Disparities between males and females were improving for 7% of the measures, not changing for 86%, and worsening for 7%.

- Person-Centered Care measures: Disparities between males and females were worsening for 10% of the measures and not changing for 90%.

- Effective Treatment measures: Disparities between males and females were improving for 9% of the measures, not changing for 86%, and worsening for 5%.

- Healthy Living measures: Disparities between males and females were worsening for 3% of the measures and not changing for 97%.

- Access measures: Disparities between males and females were improving for 12% of the measures and not changing for 88%.

- There are insufficient numbers of reliable measures of Care Coordination and Care Affordability to summarize in this way.

Slide 19

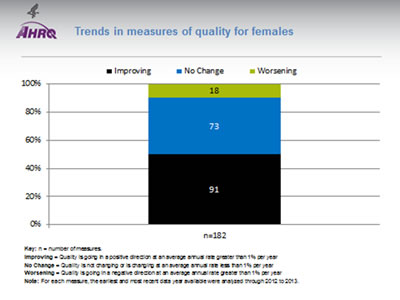

Trends in measures of quality for females

Image: Chart shows trends in measures of quality for females. Improving - 91. No Change - 73. Worsening - 18. n = 182.

Key: n = number of measures.

Improving = Quality is going in a positive direction at an average annual rate greater than 1% per year

No Change = Quality is not changing or is changing at an average annual rate less than 1% per year

Worsening = Quality is going in a negative direction at an average annual rate greater than 1% per year

Note: For each measure, the earliest and most recent data year available were analyzed through 2012 to 2013

- The quality of care for women:

- Improved for 50% (91 out of 182) of the measures.

- Worsened for 10% (18 out of 182) of the measures.

- Did not change for 40% (73 out 182) of the measures.

Slide 20

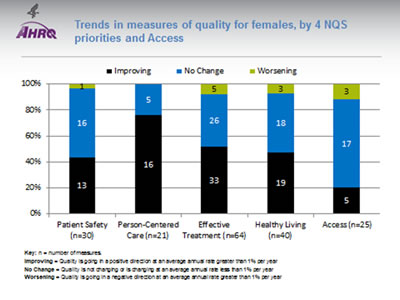

Trends in measures of quality for females, by 4 NQS priorities and Access

Image: Chart shows trends in measures of quality for females by NQS priorities. Patient Safety (n=30): Worsening - 1; No Change - 16; Improving - 13; Person-Centered Care (n=21): No Change - 5; Improving - 16. Effective Treatment (n=64): Worsening - 5; No Change - 26; Improving - 19. Healthy Living (n=40): Worsening - 3; No Change - 18; Improving - 19. Access (n=25): Worsening - 3; No Change - 17; Improving - 5.

Key: n = number of measures.

Improving = Quality is going in a positive direction at an average annual rate greater than 1% per year

No Change = Quality is not changing or is changing at an average annual rate less than 1% per year

Worsening = Quality is going in a negative direction at an average annual rate greater than 1% per year

- Overall: More measures of quality of care for women showed improvement for Person-Centered Care (76% of the measures), Effective Treatment (52%), Healthy Living (48%), and Patient Safety (43%) compared with Access (20%).

- Patient Safety measures: Quality of care for women was improving for 43% of the measures, not changing for 53%, and worsening for 4% of the measures.

- Person-Centered care measures: Quality of care for women was improving for 76% of the measures and not changing for 24%.

- Effective Treatment measures: Quality of care for women was improving for 52% of the measures, not changing for 40%, and worsening for 8%.

- Healthy Living measures: Quality of care for women was improving for 48% of the measures, not changing for 45%, and worsening for 7%.

- Access measures: Quality of care for women was improving for 20% of the measures, not changing for 68%, and worsening for 12%.

- There are insufficient numbers of reliable measures of Care Coordination and Care Affordability to summarize in this way.

Access to Health Care

Slide 21

Chartbook on Women's Health Care

Access to Health Care

Slide 22

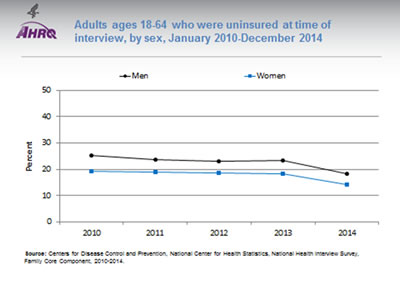

Adults ages 18-64 who were uninsured at time of interview, by sex, January 2010-December 2014

Image: Graph shows adults ages 18-64 who were uninsured at time of interview:

| Year | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 25.3 | 19.3 |

| 2011 | 23.7 | 18.9 |

| 2012 | 23.2 | 18.6 |

| 2013 | 23.3 | 18.3 |

| 2014 | 18.3 | 14.3 |

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Health Interview Survey, Family Core Component, 2010-2014.

- Importance: Health insurance facilitates entry into the health care system. Uninsured people are less likely to receive medical care and more likely to have poor health status (Healthy People 2020).

- Trends: From 2010 to 2014, the percentage of uninsured adults decreased significantly for both males and females:

- Men: from 25.3% to 18.3%.

- Women: from 19.3% to 14.3%.

- Groups With Disparities:

- In all years, women were more likely than men to be insured at time of interview.

Slide 23

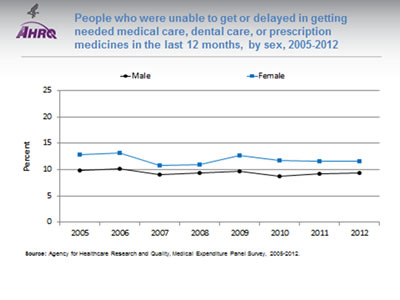

People who were unable to get or delayed in getting needed medical care, dental care, or prescription medicines in the last 12 months, by sex, 2005-2012

Image: Graph shows people who were unable to get or delayed in getting needed medical care, dental care, or prescription medicines in the last 12 months:

| Year | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 9.9 | 12.8 |

| 2006 | 10.2 | 13.1 |

| 2007 | 9.1 | 10.8 |

| 2008 | 9.4 | 11 |

| 2009 | 9.6 | 12.6 |

| 2010 | 8.8 | 11.7 |

| 2011 | 9.2 | 11.6 |

| 2012 | 9.4 | 11.6 |

Source: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2005-2012.

- Importance: Lack of timeliness can result in emotional distress, physical harm, and higher treatment costs (Boudreau, et al., 2004). Timely delivery of appropriate care can help reduce mortality and morbidity for chronic conditions, such as kidney disease (Smart & Titus, 2011).

- Trends: From 2005 to 2012, the percentage of people who were unable to get or delayed in getting care decreased from 12.8% to 11.6% for females and from 9.9% to 9.4% for males.

- Groups With Disparities:

- From 2005 to 2012, females were significantly more likely than males to be delayed or unable to get needed medical care, dental care, or prescription medicines in the last 12 months.

Slide 24

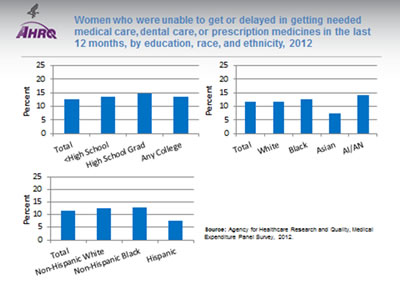

Women who were unable to get or delayed in getting needed medical care, dental care, or prescription medicines in the last 12 months, by education, race, and ethnicity, 2012

Image: Charts show women who were unable to get or delayed in getting needed medical care, dental care, or prescription medicines in the last 12 months:

By education:

- Total - 12.5.

- Less than High School - 13.4.

- High School Grad - 14.7.

- Any College - 13.6.

By race:

- Total - 11.6.

- White - 11.6.

- Black - 12.7.

- Asian - 7.4.

- AI/AN - 14.

By ethnicity:

- Total - 11.6.

- Non-Hispanic White - 12.6.

- Non-Hispanic Black - 12.9.

- Hispanic - 7.7.

- Importance: Lack of timeliness can result in emotional distress, physical harm, and higher treatment costs (Boudreau, et al., 2004) and timely delivery of appropriate care can help reduce mortality and morbidity for chronic conditions, such as kidney disease (Smart & Titus, 2011).

- Groups With Disparities:

- Education: There were no statistically significant differences observed.

- Race: Asian women were significantly less likely than White, Black, and American Indian and Alaska Native women to experience a delay in getting needed medical care, dental care, or prescription medicines in the last 12 months.

- Ethnicity: Hispanic women were significantly less likely than non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Black women to experience a delay in getting needed medical care, dental care, or prescription medicines in the last 12 months.

Patient Safety

Slide 25

Chartbook on Women's Health Care

Patient Safety

Slide 26

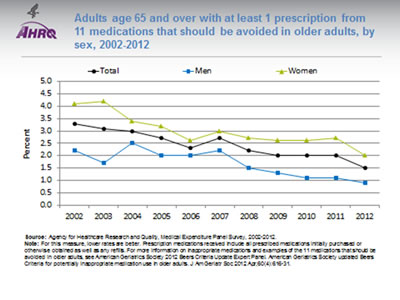

Adults age 65 and over with at least 1 prescription from 11 medications that should be avoided in older adults, by sex, 2002-2012

Image: Graph shows adults age 65 and over with at least 1 prescription from 11 medications that should be avoided in older adults:

| Year | Total | Women | Men |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 3.3 | 4.1 | 2.2 |

| 2003 | 3.1 | 4.2 | 1.7 |

| 2004 | 3 | 3.4 | 2.5 |

| 2005 | 2.7 | 3.2 | 2 |

| 2006 | 2.3 | 2.6 | 2 |

| 2007 | 2.7 | 3 | 2.2 |

| 2008 | 2.2 | 2.7 | 1.5 |

| 2009 | 2 | 2.6 | 1.3 |

| 2010 | 2 | 2.6 | 1.1 |

| 2011 | 2 | 2.7 | 1.1 |

| 2012 | 1.5 | 2 | 0.9 |

Source: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2002-2012.

Note: For this measure, lower rates are better. Prescription medications received include all prescribed medications initially purchased or otherwise obtained as well as any refills. For more information on inappropriate medications and examples of the 11 medications that should be avoided in older adults, see American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012 Apr;60(4):616-31.

- Importance: Some drugs that are prescribed for older patients are known to be potentially harmful for this age group (AGS, 2012). Adverse drug events occur in 15% or more of older patients presenting to offices, hospitals, and extended care facilities. These events are potentially preventable up to 50% of the time. Women account for between one-third and one-half more incidents (Pretorius, et al., 2013).

- Overall Rate: In 2012, 1.5% of adults age 65 and over were prescribed at least 1 medication from 11 medications that should be avoided in older adults. In 2012, the percentage was 0.9% for men and 2% for women (more than double).

- Trends:

- From 2002 to 2012, the percentage of adults age 65 and over who were prescribed at least 1 medication from 11 medications that should be avoided in older adults decreased from 3.3% to 1.5%.

- From 2002 to 2012, the percentage of men age 65 and over who were prescribed at least 1 medication from 11 medications that should be avoided in older adults decreased from 2.2% to 0.9% and the percentage of women for the same measure decreased from 4.1% to 2%.

- From 2002 to 2012, the percentage of adults age 65 and over who received potentially inappropriate prescription medications decreased overall and for all racial and ethnic groups and all income groups (data not shown).

- Groups With Disparities: In all years from 2002 to 2012, men were less likely than women to be prescribed at least 1 medication from 11 medications that should be avoided in older adults.

Slide 27

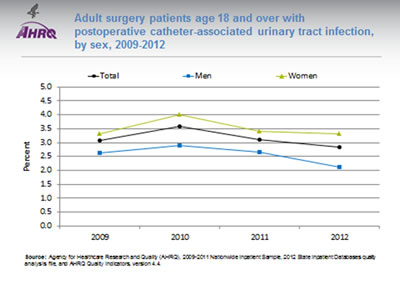

Adult surgery patients age 18 and over with postoperative catheter-associated urinary tract infection, by sex, 2009-2012

Image: Graph shows adult surgery patients age 18 and over with postoperative catheter-associated urinary tract infection:

Source: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), 2009-2011 Nationwide Inpatient Sample, 2012 State Inpatient Databases quality analysis file, and AHRQ Quality Indicators, version 4.4.

| Year | Total | Women | Men |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 3.1 | 3.3 | 2.6 |

| 2010 | 3.6 | 4.0 | 2.9 |

| 2011 | 3.1 | 3.4 | 2.7 |

| 2012 | 2.8 | 3.3 | 2.1 |

- Importance: The urinary tract is a common site of healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) and an indicator of hospital patient safety. Urinary catheter use and specific comorbid conditions can increase the risk of developing a urinary tract infection (UTI). Approximately 40% of all HAIs are attributed to catheter-associated UTI (CAUTI) (Lo, et al., 2008).

- Overall Rate: In 2012, the percentage of women with CAUTI was 3.3%, and the percentage of men with CAUTI was 2.1%.

- Trends:

- In general, CAUTI percentages decreased overall from 3.6 in 2010 to 2.8 in 2012.

- From 2009 to 2012, there was no statistically significant change in the percentage of women with postoperative CAUTI.

- Groups With Disparities:

- From 2009 to 2012, the percentage of adults with postoperative CAUTI was higher for women compared with men.

Slide 28

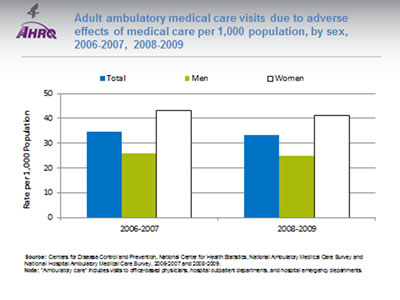

Adult ambulatory medical care visits due to adverse effects of medical care per 1,000 population, by sex, 2006-2007, 2008-2009

Image: Charts show adult ambulatory medical care visits due to adverse effects of medical care per 1,000 population: 2006-2007: Total - 34.6; Men - 25.8; Women - 43.1. 2008-2009: Total - 33.2; Men - 25; Women - 41.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey and National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, 2006-2007 and 2008-2009.

Note: "Ambulatory care" includes visits to office-based physicians, hospital outpatient departments, and hospital emergency departments

- Importance: Adverse effects of medical care can arise from medical and surgical procedures as well as from adverse drug reactions. Although patient safety initiatives focus mainly on inpatient hospital events, adverse effects of medical care are much more commonly treated at visits to outpatient settings, with more than 12 million such visits occurring annually. Providers treating adverse events in outpatient settings may include office-based physicians, hospital outpatient departments, and hospital emergency departments. Events treated in ambulatory settings may be less severe than those occurring in inpatient settings. Some adverse events, such as known side effects of appropriately prescribed medications, may be unavoidable, while others may be considered medical errors. Although the measure here does not distinguish between the two types of events, it provides an overall sense of the burden these events place on the population.

- Overall Rate: In 2008-2009, the rate of ambulatory care visits for adverse effects of medical care was 33.2 per 1,000 population.

- Groups With Disparities: From 2006 to 2009, the rate of ambulatory care visits for adverse effects of medical care was higher for women than for men.

Slide 29

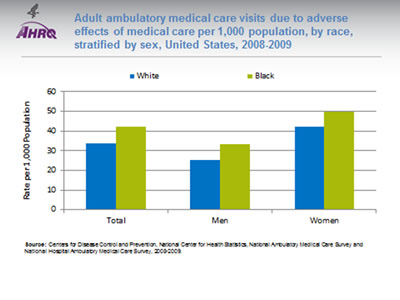

Adult ambulatory medical care visits due to adverse effects of medical care per 1,000 population, by race, stratified by sex, United States, 2008-2009

Image: Chart shows adult ambulatory medical care visits due to adverse effects of medical care per 1,000 population: Total: White - 33.6; Black - 42.1. Men: White - 25.1; Black - 33.2. Women: White - 42; Black - 49.8.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey and National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, 2008-2009.

- Groups With Disparities:

- In 2008-2009, Blacks had higher rates of ambulatory care visits for adverse effects of medical care compared with Whites.

Person- and Family-Centered Care

Slide 30

Chartbook on Women's Health Care

Person- and Family-Centered Care

Slide 31

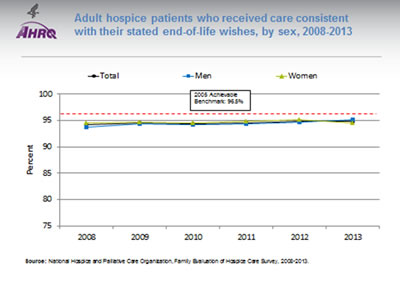

Adult hospice patients who received care consistent with their stated end-of-life wishes, by sex, 2008-2013

Image: Graph shows adult hospice patients who received care consistent with their stated end-of-life wishes:

| Year | Total | Women | Men |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 94.2 | 94.6 | 93.8 |

| 2009 | 94.6 | 94.7 | 94.4 |

| 2010 | 94.4 | 94.6 | 94.2 |

| 2011 | 94.6 | 94.9 | 94.4 |

| 2012 | 94.8 | 95.1 | 94.7 |

| 2013 | 94.8 | 94.6 | 95.1 |

Benchmark: 96.5%.

Source: National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, Family Evaluation of Hospice Care Survey, 2008-2013.

- Importance:

- Hospice care is generally delivered at the end of life to patients with a terminal illness or condition who desire palliative medical care.

- Hospice care also includes practical, psychosocial, and spiritual support for the patient and family. The goal of end-of-life care is to achieve a "good death," defined by the Institute of Medicine as "…free from avoidable distress and suffering for patients, families, and caregivers; in general accord with the patients' and families' wishes; and reasonably consistent with clinical, cultural, and ethical standards" (Field & Cassel, 1997).

- Overall Rate: From 2008 to 2013, the overall percentage of adult hospice patients who received care consistent with their stated end-of-life wishes remained constant around 94%.

- Trends: From 2008 to 2013, the percentage of female hospice patients who received care consistent with their stated end-of-life wishes improved in 3 of 5 years.

- Groups With Disparities: From 2008 to 2012, female hospice patients were more likely to receive care consistent with their stated end-of-life wishes compared to men.

- Achievable Benchmark:

- The 2008 top 5 State achievable benchmark for hospice patients who received care consistent with their stated end-of-life wishes was 96.5%. The top 5 States that contributed to the achievable benchmark are Maine, Minnesota, Mississippi, New Hampshire, and Tennessee.

- At the current rate of change, the total population could achieve the benchmark in 14 years, men in 9 years, and women in 12 years.

Slide 32

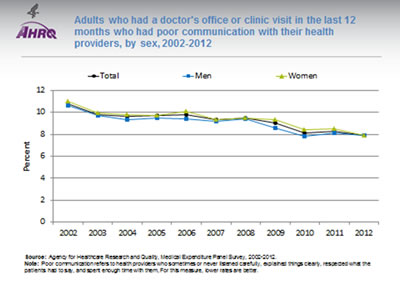

Adults who had a doctor's office or clinic visit in the last 12 months who had poor communication with their health providers, by sex, 2002-2012

Image: Graph shows adults who had a doctor's office or clinic visit in the last 12 months who had poor communication with their health providers:

| Sex | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 10.8 | 9.8 | 9.6 | 9.7 | 9.8 | 9.3 | 9.5 | 9 | 8.1 | 8.3 | 7.9 |

| Men | 10.6 | 9.7 | 9.3 | 9.5 | 9.4 | 9.2 | 9.4 | 8.6 | 7.8 | 8.1 | 7.9 |

| Women | 11 | 9.9 | 9.8 | 9.7 | 10.1 | 9.3 | 9.5 | 9.3 | 8.4 | 8.5 | 7.9 |

Source: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2002-2012.

Note: Poor communication refers to health providers who sometimes or never listened carefully, explained things clearly, respected what the patients had to say, and spent enough time with them, For this measure, lower rates are better

- Importance: Patient-centered care is supported by good provider-patient communication so that patients' needs and wants are understood and addressed and patients understand and participate in their own care (Hurtado, et al., 2001; Anderson, 2002). This style of care has been shown to improve patients' health and health care (Heidenreich, 2013) and is reflected in this composite measure. Unfortunately, there are barriers to good communication: more than one-third of adults in the United States have low health literacy (Kountz, 2009), which means they lack the "capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions" (Selden, et al., 2000). Low health literacy is associated with higher mortality, higher rates of hospitalization, and poor self-management skills for chronic disease (Mitchell, et al., 2012).

- Trends: From 2002 to 2011, the percentage of adults who had poor communication with their health providers was slightly higher for women than for men, but in 2012 the percentages for men and women were the same.

Slide 33

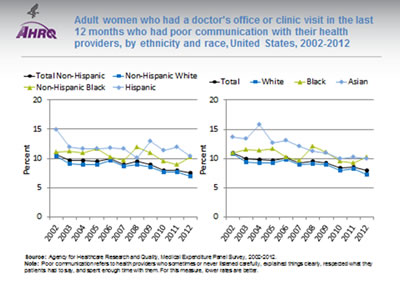

Adult women who had a doctor's office or clinic visit in the last 12 months who had poor communication with their health providers, by ethnicity and race, United States, 2002-2012

Image: Graphs show adult women who had a doctor's office or clinic visit in the last 12 months who had poor communication with their health providers:

Left Graph:

| Year | Hispanic | Non-Hispanic Black | Non-Hispanic White | Total Non-Hispanic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 14.9 | 11.1 | 10.3 | 10.6 |

| 2003 | 12 | 11.2 | 9.1 | 9.6 |

| 2004 | 11.6 | 11 | 9 | 9.6 |

| 2005 | 11.7 | 11.7 | 9 | 9.5 |

| 2006 | 11.8 | 10.2 | 9.6 | 9.9 |

| 2007 | 11.7 | 9.7 | 8.6 | 9 |

| 2008 | 10.1 | 12 | 9 | 9.5 |

| 2009 | 12.9 | 11 | 8.5 | 8.9 |

| 2010 | 11.4 | 9.5 | 7.6 | 8 |

| 2011 | 12 | 8.9 | 7.7 | 8 |

| 2012 | 10.3 | 10.2 | 6.9 | 7.5 |

Right Graph:

| Year | Total | Asian | Black | White |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 11 | 13.7 | 11 | 10.8 |

| 2003 | 9.9 | 13.4 | 11.5 | 9.4 |

| 2004 | 9.8 | 15.8 | 11.4 | 9.2 |

| 2005 | 9.7 | 12.7 | 11.7 | 9.3 |

| 2006 | 10.1 | 13.1 | 10.3 | 9.8 |

| 2007 | 9.3 | 12.1 | 9.7 | 9 |

| 2008 | 9.5 | 11.2 | 12.1 | 9.1 |

| 2009 | 9.3 | 11 | 11.1 | 9 |

| 2010 | 8.4 | 10 | 9.5 | 8 |

| 2011 | 8.5 | 10.2 | 9.3 | 8.2 |

| 2012 | 7.9 | 10 | 10.3 | 7.3 |

Source: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2002-2012.

Note: Poor communication refers to health providers who sometimes or never listened carefully, explained things clearly, respected what they patients had to say, and spent enough time with them. For this measure, lower rates are better.

- Trends:

- From 2002 to 2012, the percentage of women reporting poor communication with their health providers was lower for non-Hispanic White women than for Hispanics and non-Hispanic Blacks.

- From 2002 to 2012, the percentage of White women who reported poor communication with their health providers decreased significantly from 10.3% to 6.9%.

- Groups With Disparities:

- In all years, Hispanic women were significantly more likely than non-Hispanic Blacks and Whites to report poor communication.

- In 10 of 11 years, non-Hispanic Black women were more likely than non-Hispanic White women to report poor communication with health providers.

Slide 34

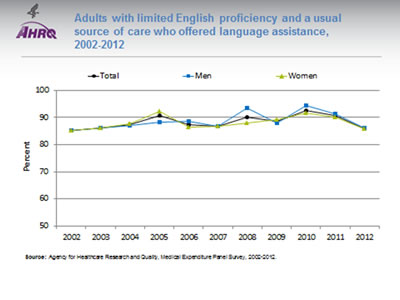

Adults with limited English proficiency and a usual source of care who offered language assistance, 2002-2012

Image: Graph shows adults with limited English proficiency and a usual source of care who offered language assistance:

| Year | Total | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 85.2 | 85.3 | 85.2 |

| 2003 | 86 | 86 | 86.1 |

| 2004 | 87.3 | 86.9 | 87.5 |

| 2005 | 90.8 | 88.3 | 92.1 |

| 2006 | 87.3 | 88.7 | 86.5 |

| 2007 | 86.7 | 86.8 | 86.7 |

| 2008 | 90 | 93.4 | 88.1 |

| 2009 | 88.7 | 87.9 | 89.2 |

| 2010 | 92.7 | 94.3 | 91.6 |

| 2011 | 90.6 | 91.4 | 90.2 |

| 2012 | 85.9 | 86.1 | 85.8 |

Source: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2002-2012.

- Importance:

- Language barriers in health care are associated with decreases in quality of care, safety, and patient and clinician satisfaction and contribute to health disparities, even among people with insurance.

- The Federal Government has issued 14 culturally and linguistically appropriate services standards (https://www.thinkculturalhealth.hhs.gov/clas). These standards, which are directed at health care organizations, are also encouraged for individual providers to improve accessibility of their practices.

- Overall Rate: In 2012, the overall percentage of adults with limited English proficiency and a usual source of care (USC) who offered language assistance was 85.9%.

Communication and Care Coordination

Slide 35

Chartbook on Women's Health Care

Communication and Care Coordination

Slide 36

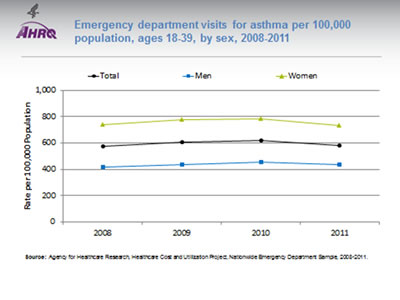

Emergency department visits for asthma per 100,000 population, ages 18-39, by sex, 2008-2011

Image: Graph shows emergency department visits for asthma per 100,000 population:

| Year | Total | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 578 | 419.1 | 739.3 |

| 2009 | 604.2 | 436.4 | 774.6 |

| 2010 | 616.3 | 453.9 | 781.2 |

| 2011 | 582 | 435.6 | 730.6 |

Source: Agency for Healthcare Research, Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, Nationwide Emergency Department Sample, 2008-2011.

- Importance:

- Regardless of age, race, ethnicity, sex, class, income, or personal history, advances in asthma treatment mean that asthma control is achievable for nearly all persons with asthma, but only if clinicians and patients join together to follow the asthma guidelines (NHLBI).

- People with asthma need proper medical care to manage their disease. When their asthma is controlled with routine care and education, they are less likely to visit emergency departments and urgent care facilities for asthma-related treatments (CDC).

- In 2013, asthma prevalence was 6.2% among males and 8.3% among females (CDC).

- Trends:

- From 2008 to 2011, the overall rate of emergency department visits for asthma increased from 578 to 582 per 100,000 population.

- Rates of emergency department visits for asthma among women decreased from 739.3 to 730.6 and among men increased from 419.1 to 435.6 per 100,000 population.

- None of these changes were statistically significant.

- Groups With Disparities:

- In all years, women were much more likely (more than 1.5 times) to have an emergency department visit for asthma than men.

- The gap between men and women grew smaller, indicating improvement.

Slide 37

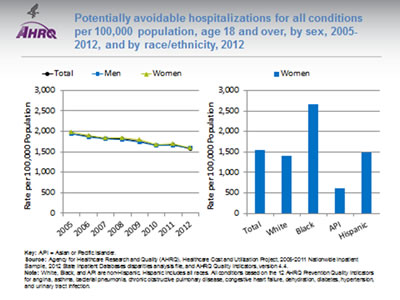

Potentially avoidable hospitalizations for all conditions per 100,000 population, age 18 and over, by sex, 2005-2012, and by race/ethnicity, 2012

Image: Charts show potentially avoidable hospitalizations for all conditions per 100,000 population:

Left Graph (Sex):

| Year | Total | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 1941.23 | 1929.01 | 1969.24 |

| 2006 | 1873.5 | 1864.25 | 1898.64 |

| 2007 | 1814.25 | 1810.49 | 1833.97 |

| 2008 | 1814.54 | 1797.56 | 1845.96 |

| 2009 | 1756.53 | 1738.55 | 1787.62 |

| 2010 | 1658.32 | 1646.97 | 1683.02 |

| 2011 | 1669.29 | 1649.46 | 1701.29 |

| 2012 | 1582.43 | 1584.32 | 1596.32 |

Right Chart (Women, by Race/Ethnicity):

- Total - 1537.5.

- White - 1401.8.

- Black - 2653.9.

- API - 615.9.

- Hispanic - 1482.9.

Key: API = Asian or Pacific Islander.

Source: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, 2005-2011 Nationwide Inpatient Sample, 2012 State Inpatient Databases disparities analysis file, and AHRQ Quality Indicators, version 4.4.

Note: White, Black, and API are non-Hispanic. Hispanic includes all races. All conditions based on the 12 AHRQ Prevention Quality Indicators for angina, asthma, bacterial pneumonia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, dehydration, diabetes, hypertension, and urinary tract infection.

- Importance: Hospitalization is expensive. Preventing avoidable hospitalizations could reduce health care costs. Not all hospitalizations that the AHRQ Prevention Quality Indicators (PQIs) track are preventable. But ambulatory care-sensitive conditions are those for which good outpatient care can prevent the need for hospitalization or for which early intervention can prevent complications or more severe disease. The AHRQ PQIs track these conditions using hospital discharge data.

- Trends: From 2005 to 2012, overall rates for potentially avoidable hospitalizations for all conditions improved from 1,941 to 1,582 per 100,000 population. Rates improved among men and women.

- Groups With Disparities:

- In all years, there were no statistically significant differences between men and women.

- In 2012, Asian and Pacific Islander (API) women were less likely than White women to have potentially avoidable hospitalizations (615.9 compared with 1,401.8 per 1000,000 population). Black women were more likely than White women to have potentially avoidable hospitalizations (2,653.9 compared with 1,401.8 per 1000,000 population).

Slide 38

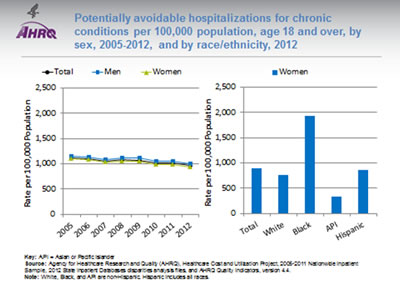

Potentially avoidable hospitalizations for chronic conditions per 100,000 population, age 18 and over, by sex, 2005-2012, and by race/ethnicity, 2012

Image: Charts show potentially avoidable hospitalizations for chronic conditions per 100,000 population:

Left Graph (Sex):

| Year | Total | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 1118.41 | 1145.89 | 1103.15 |

| 2006 | 1102.51 | 1135.77 | 1083.04 |

| 2007 | 1053.36 | 1090.15 | 1030.14 |

| 2008 | 1078.22 | 1114.3 | 1057.76 |

| 2009 | 1070.71 | 1108.93 | 1047.8 |

| 2010 | 1012.91 | 1054 | 986.96 |

| 2011 | 1012.3 | 1047.37 | 991.62 |

| 2012 | 960.95 | 1009.32 | 929.15 |

Right Chart (Women, by Race/Ethnicity):

- Total - 898.1.

- White - 766.3.

- Black - 1926.9.

- API - 338.9.

- Hispanic - 868.6.

Key: API = Asian or Pacific Islander

Source: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, 2005-2011 Nationwide Inpatient Sample, 2012 State Inpatient Databases disparities analysis files, and AHRQ Quality Indicators, version 4.4.

Note: White, Black, and API are non-Hispanic. Hispanic includes all races.

- Importance: Hospitalization is expensive. Preventing avoidable hospitalizations could reduce health care cost. Not all hospitalizations that the AHRQ PQIs track are preventable. But ambulatory care-sensitive conditions are those for which good outpatient care can prevent the need for hospitalization or for which early intervention can prevent complications or more severe disease. The AHRQ PQIs track these conditions using hospital discharge data. Hospitalizations for chronic conditions include diabetes and congestive heart failure.

- Trends: From 2005 to 2012, overall rates of potentially avoidable hospitalizations for chronic conditions improved from 1,118 to 961 per 100,000 population. The rates improved among both men and women.

- Groups With Disparities:

- In all years, there were no statistically significant differences between men and women in the rate of potentially avoidable hospitalization for chronic conditions.

- In 2012, API women were less likely than White women to have potentially avoidable hospitalizations for chronic conditions (338.9 compared with 766.3 per 100,000 population). Black women were more likely than White women to have potentially avoidable hospitalization for chronic conditions (1,926.9 compared with 766.3 per 100,000 population).

Slide 39

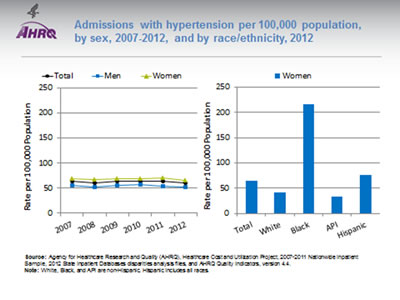

Admissions with hypertension per 100,000 population, by sex, 2007-2012, and by race/ethnicity, 2012

Image: Charts show admissions with hypertension per 100,000 population:

Left Graph (Sex):

| Year | Total | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 63.4 | 54.9 | 69.4 |

| 2008 | 61.2 | 52.3 | 67.7 |

| 2009 | 64.1 | 56.1 | 69.6 |

| 2010 | 64.4 | 56.5 | 69.7 |

| 2011 | 63.6 | 54.1 | 70.1 |

| 2012 | 60.1 | 52.5 | 65.0 |

Right Chart (Women, by Race/Ethnicity):

- Total - 65.1.

- White - 41.8.

- Black - 215.6.

- API - 34.

- Hispanic - 75.9.

Source: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, 2007-2011 Nationwide Inpatient Sample, 2012 State Inpatient Databases disparities analysis files, and AHRQ Quality Indicators, version 4.4.

Note: White, Black, and API are non-Hispanic. Hispanic includes all races.

- Importance: About 70 million American adults (29%) have high blood pressure (Nwankwo, et al., 2013). High blood pressure costs the Nation $46 billion each year. This total includes the cost of health care services, medications to treat high blood pressure, and missed days of work. For people age 65 and over, high blood pressure affects more women than men (Mozzafarian, et al., 2015).

- Trends:

- From 2007 to 2012, the overall rate of admissions with hypertension improved from 63.4 to 60.1 per 100,000 population.

- During this time, the rate worsened among men, but there were no statistically significant changes among women.

- Groups With Disparities:

- In 2012, overall, women had higher rates of admissions with hypertension than men.

- In 2012, the rate of admissions with hypertension for Black women was more than five times the rate for White women.

Slide 40

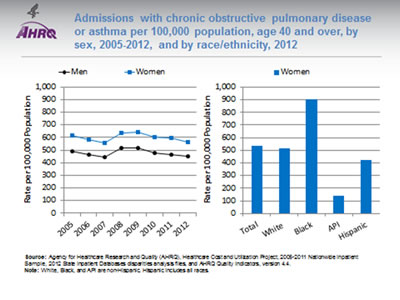

Admissions with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma per 100,000 population, age 40 and over, by sex, 2005-2012, and by race/ethnicity, 2012

Image: Charts show admissions with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma per 100,000 population:

Left Graph (Sex):

| Year | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 490.27 | 616.09 |

| 2006 | 461.19 | 580.04 |

| 2007 | 443.83 | 554.97 |

| 2008 | 519.02 | 633.09 |

| 2009 | 514.84 | 643.24 |

| 2010 | 478.32 | 602.99 |

| 2011 | 466.03 | 597.83 |

| 2012 | 452.95 | 560.48 |

Right Chart (Women, by Race/Ethnicity):

- Total - 537.6.

- White - 512.8.

- Black - 906.

- API - 139.9.

- Hispanic - 424.9.

Source: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, 2005-2011 Nationwide Inpatient Sample, 2012 State Inpatient Databases disparities analysis files, and AHRQ Quality Indicators, version 4.4.

Note: White, Black, and API are non-Hispanic. Hispanic includes all races.

- Importance: According to the American Lung Association (2013), more than 7 million women in the United States live with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Millions more have the disease but are undiagnosed, possibly due to the common misdiagnosis of asthma for female COPD patients. In fact, the number of deaths among women from COPD has increased fourfold over the past three decades and, since 2000, more women than men in this country have died of the disease.

- Trends: From 2005 to 2012, there were no statistically significant changes overall among women or men in the rate of admissions with COPD.

- Groups With Disparities:

- In all years, women had higher rates of admissions with COPD than men.

- In 2012, rates of admission with COPD per 100,000 population were significantly lower for API (139.9) and Hispanic women (424.9) than White women (512.8).

- The rate of admissions with COPD for Black females was nearly twice the rate of White females.

Slide 41

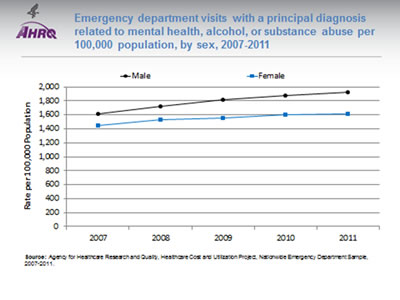

Emergency department visits with a principal diagnosis related to mental health, alcohol, or substance abuse per 100,000 population, by sex, 2007-2011

Image: Graph shows emergency department visits with a principal diagnosis related to mental health, alcohol, or substance abuse per 100,000 population:

| Year | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 1613.4 | 1444.8 |

| 2008 | 1722.4 | 1528.5 |

| 2009 | 1821.9 | 1556.7 |

| 2010 | 1881.9 | 1599.4 |

| 2011 | 1928.6 | 1609.1 |

Source: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, Nationwide Emergency Department Sample, 2007-2011

- Importance: An estimated one in three individuals has suffered from a mental health or substance abuse condition within the last 12 months, yet the community treatment system to support services for these individuals is regarded by the Institute of Medicine as ineffective (Owens, et al., 2010). In 2011, about 609,000 of the 1.84 million admissions (33.1%) to substance abuse treatment were female, and 1.23 million were male (66.9%). However, specific types of mental disorders vary by sex. For instance, women are more likely than men to experience an anxiety or mood disorder, such as depression, while men are more likely to experience an impulse control or substance use disorder (HRSA, 2013).

- Trends: From 2007 to 2011, the rates of emergency department visits with a principal diagnosis related to mental health, alcohol, or substance abuse worsened overall and for both males and females.

- Groups With Disparities: In all years, females were less likely to have an emergency department visit with a principal diagnosis related to mental health, alcohol, or substance abuse compared with males.

Effective Treatment of Leading Causes of Morbidity and Mortality

Slide 42

Chartbook on Women's Health

Effective Treatment of Leading Causes of Morbidity and Mortality

Slide 43

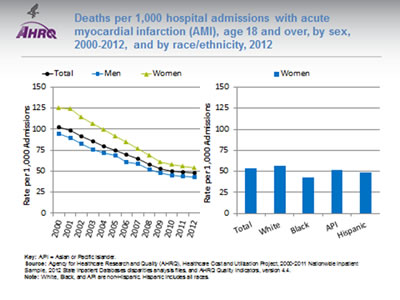

Deaths per 1,000 hospital admissions with acute myocardial infarction (AMI), age 18 and over, by sex, 2000-2012, and by race/ethnicity, 2012

Image: Chart shows deaths per 1,000 hospital admissions with acute myocardial infarction (AMI):

Left Graph (Sex):

| Year | Total | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 102.4 | 94.0 | 125.4 |

| 2001 | 98.3 | 89.2 | 124.0 |

| 2002 | 91.8 | 82.0 | 114.6 |

| 2003 | 85.2 | 75.8 | 106.1 |

| 2004 | 79.9 | 71.7 | 99.2 |

| 2005 | 74.7 | 68.5 | 91.1 |

| 2006 | 70.0 | 60.8 | 84.8 |

| 2007 | 65.0 | 58.9 | 76.4 |

| 2008 | 57.9 | 52.3 | 69.0 |

| 2009 | 53.0 | 48.0 | 60.7 |

| 2010 | 50.2 | 45.1 | 57.8 |

| 2011 | 48.7 | 44.1 | 56.0 |

| 2012 | 47.6 | 43.0 | 54.3 |

Right Chart (Women by Race/Ethnicity):

- Total - 53.7.

- White- 56.1.

- Black - 42.4.

- API - 51.8.

- Hispanic - 48.3.

Key: API = Asian or Pacific Islander.

Source: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, 2000-2011 Nationwide Inpatient Sample, 2012 State Inpatient Databases disparities analysis files, and AHRQ Quality Indicators, version 4.4.

Note: White, Black, and API are non-Hispanic. Hispanic includes all races.

- Importance: Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the number one killer of women worldwide, accounting for one-third of all deaths. In the United States, more than 38 million women are living with CVD, and the at-risk population is even larger (Collins-Sharp, 2012). Heart attack, or acute myocardial infarction, is a common life-threatening condition that requires rapid recognition and efficient treatment in a hospital to reduce the risk of serious heart damage and death (Collins-Sharp, 2012).

- Trends:

- From 2000 to 2012, the rate of deaths per 1,000 hospital admissions with acute myocardial infarction improved overall and for both men and women.

- The rate for women decreased from 125.4 to 54.3 per 1,000 admissions.

- The rate for men decreased from 94 to 43 per 1,000 admissions.

- Groups With Disparities:

- In all years from 2000 to 2012, women had higher rates of death per 1,000 hospital admissions with acute myocardial infarction than men.

- In 2012, Black and Hispanic women had lower rates of death than White women.

Slide 44

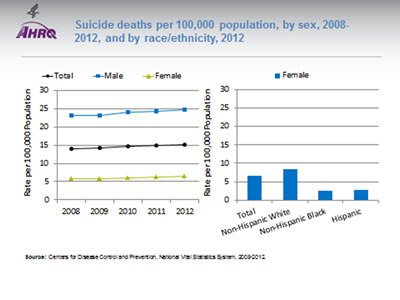

Suicide deaths per 100,000 population, by sex, 2008-2012, and by race/ethnicity, 2012

Image: Charts show suicide deaths per 100,000 population:

Left Graph (Sex):

| Year | Total | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 14 | 23 | 5.7 |

| 2009 | 14.2 | 23.2 | 5.9 |

| 2010 | 14.6 | 23.9 | 6 |

| 2011 | 14.9 | 24.2 | 6.3 |

| 2012 | 15.2 | 24.6 | 6.5 |

Right Chart (Women by Race/Ethnicity):

- Total- 6.5.

- Non-Hispanic White - 8.3.

- Non-Hispanic Black - 2.5.

- Hispanic - 2.7.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Vital Statistics System, 2008-2012.

- Importance: According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Xu, et al., 2014), the rate for the top 10 leading causes of death has decreased or held steady, except the 10th leading cause of death in the United States, suicide. Rates of attempted suicide vary considerably among demographic groups. While males are 4 times more likely than females to die by suicide, females attempt suicide 3 times as often as males. The economic cost of suicide death in the United States was estimated in 2010 to be more than $44 billion annually. With the burden of suicide falling most heavily on adults of working age, the cost to the economy results almost entirely from lost wages and work productivity. In 2013 (the most recent year for which full data are available), 41,149 suicides were reported (CDC WISQARS, 2013; American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, 2015).

- Trends: From 2008 to 2012, suicide deaths among females showed a statistically significant increase. There were no statistically significant changes overall or among males.

- Groups With Disparities:

Slide 45

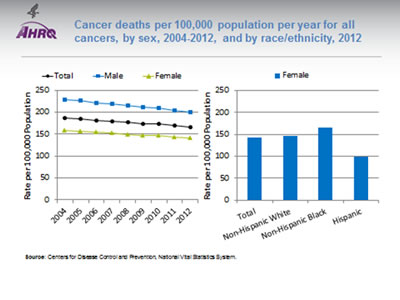

Cancer deaths per 100,000 population per year for all cancers, by sex, 2004-2012, and by race/ethnicity, 2012

Image: Charts show cancer deaths per 100,000 population per year for all cancers:

Left Graph (Sex):

| Year | Total | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 186.8 | 229.5 | 158.2 |

| 2005 | 185.1 | 227.2 | 156.7 |

| 2006 | 181.8 | 221.7 | 154.7 |

| 2007 | 179.3 | 218.8 | 152.3 |

| 2008 | 176.4 | 214.9 | 149.6 |

| 2009 | 173.5 | 210.9 | 147.4 |

| 2010 | 172.8 | 209.9 | 146.7 |

| 2011 | 169 | 204 | 144 |

| 2012 | 166.5 | 200.3 | 142.1 |

Right Chart (Women by Race/Ethnicity):

- Total - 142.1.

- Non-Hispanic White - 146.

- Non-Hispanic Black - 165.7.

- Hispanic - 99.3.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Vital Statistics System.

- Importance: In 2015, there will be an estimated 1,658,370 new cancer cases diagnosed and 589,430 cancer deaths in the United States (ACS, 2015). AHRQ estimates that the direct medical costs (total of all health care expenditures) for cancer in the United States in 2011 were $88.7 billion.

- Trends: From 2004 to 2012, cancer deaths overall and among both females and males showed statistically significant improvement.

- Groups With Disparities:

- In 2012, overall, females had lower rates of cancer deaths per 100,000 hospital admissions than males.

- Females from all ethnic groups had lower rates of cancer deaths than males.

Healthy Living

Slide 46

Chartbook on Women's Health

Healthy Living

Slide 47

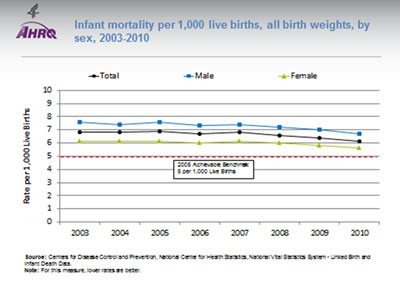

Infant mortality per 1,000 live births, all birth weights, by sex, 2003-2010

Image: Graph shows infant mortality per 1,000 live births:

| Sex | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 6.8 | 6.8 | 6.9 | 6.7 | 6.8 | 6.6 | 6.4 | 6.1 |

| Male | 7.6 | 7.4 | 7.6 | 7.3 | 7.4 | 7.2 | 7.0 | 6.7 |

| Female | 6.1 | 6.1 | 6.1 | 6.0 | 6.1 | 6.0 | 5.8 | 5.6 |

2005 Acheivable Benchmark: 5 per 1,000 Live Births.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System—Linked Birth and Infant Death Data.

Note: For this measure, lower rates are better

- Importance: Infant mortality, or the death of a child within the first year, is an important indicator of population health that reflects the well-being of mothers and families, including the broader socioeconomic and environmental factors that influence one's health and access to health care. Approximately two-thirds of infant deaths occur in the neonatal period or within 1 month and one-third occur in the postneonatal period from 1 month to less than 1 year. Neonatal mortality is predominantly related to prematurity, congenital anomalies, and other perinatal conditions. Postneonatal mortality is mostly attributable to sudden unexpected infant death (SUID), congenital anomalies, infection, and injury (Child Health USA, 2014).

- Overall Rate: In 2010, the infant mortality rate was 6.1 per 1,000 live births.

- Trends: From 2003 to 2010, the infant mortality rate per 1,000 live births for all weights improved overall (from 6.8 to 6.1), for males (from 7.6 to 6.7), and for females (from 6.1 to 5.6).

- Groups With Disparities: In all years, the infant mortality rate per 1,000 live births was lower for females than for males.

- Achievable Benchmark:

- The 2005 top 5 State achievable benchmark for infant mortality was 5 per 1,000 live births. The top 5 States that contributed to the achievable benchmark are Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, Utah, and Washington.

- At the current rate of change, the total population could achieve the benchmark in 12 years, males in 15 years, and females in 10 years.

Slide 48

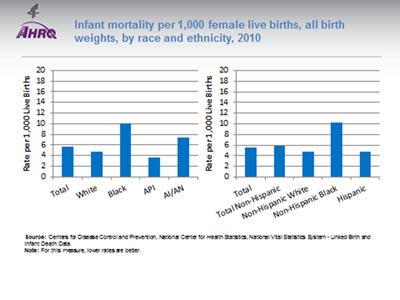

Infant mortality per 1,000 female live births, all birth weights, by race and ethnicity, 2010

Image: Charts show infant mortality per 1,000 female live births:

By Race:

- Total - 5.6.

- White- 4.7.

- Black - 10.1.

- API - 3.6.

- AI/AN - 7.4.

By Ethnicity:

- Total- 5.6.

- Total Non-Hispanic - 5.8.

- Non-Hispanic White - 4.7.

- Non-Hispanic Black - 10.3.

- Hispanic - 4.8.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System—Linked Birth and Infant Death Data.

Note: For this measure, lower rates are better.

- Overall Rate: In 2010, the total infant mortality rate among females was 5.6 per 1,000 live births.

- Groups With Disparities:

- In 2010, the infant mortality rate per 1,000 live births was higher for American Indian and Alaska Native (7.4) and Black infants (10.1) compared with White infants (4.7).

- The rate was lower for API infants (3.6) compared with White infants.

- In 2010, the infant mortality rate per 1,000 live births was worse for non-Hispanic Black (10.3 per 1,000) and total non-Hispanic (5.8) compared with non-Hispanic White infants (4.7).

Slide 49

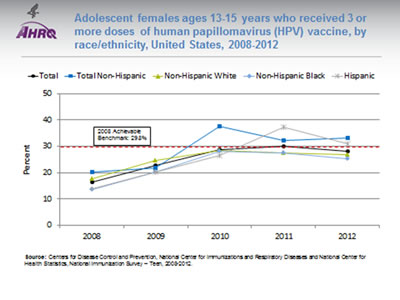

Adolescent females ages 13-15 years who received 3 or more doses of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine, by race/ethnicity, United States, 2008-2012

Image: Graph shows adolescent females ages 13-15 years who received 3 or more doses of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine:

| Race / Ethnicity | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 16.6 | 22.9 | 28.6 | 30.0 | 28.1 |

| Total Non-Hispanic | 20.3 | 21.9 | 37.7 | 32.3 | 33.2 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 13.6 | 20.2 | 28.2 | 27.4 | 25.2 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 17.7 | 24.7 | 28.3 | 27.5 | 26.8 |

| Hispanic | 13.9 | 20.1 | 26.7 | 37.3 | 30.9 |

2008 Achievable Benchmark: 29.8%.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Immunizations and Respiratory Diseases and National Center for Health Statistics, National Immunization Survey—Teen, 2008-2012.

- Importance: A licensed HPV vaccine has been available since 2006. It is recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) for routine vaccination of adolescent girls at age 11 or 12 years with 3 doses of either HPV2 or HPV4, which can be started at age 9 years, with catchup vaccinations at later ages for females (13-26 years). The vaccine can be safely coadministered with other routinely recommended vaccines. ACIP recommends administration of all age-appropriate vaccines during a single visit (MMWR, 2010).

- Overall Rate: In 2012, the percentage of adolescent females ages 13-15 years who received 3 or more doses of HPV vaccine was 28.1%.

- Trends:

- From 2008 to 2012, overall, the percentage of adolescent females ages 13-15 years who received 3 or more doses of HPV vaccine improved from 16.6% to 28.1%.

- From 2008 to 2012, the percentage of adolescent females ages 13-15 years who received 3 or more doses of HPV vaccine improved for non-Hispanic Blacks (from 13.6% to 25.2%) and Hispanics (from 13.9% to 30.9%).

- Achievable Benchmark:

- The 2008 top 4 State achievable benchmark for adolescent females ages 13-15 years who received 3 or more doses of HPV vaccine was 29.8%. The top 4 States that contributed to the achievable benchmark are Delaware, New York, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island.

- At the current rate of change, the total population could achieve the benchmark in less than a year, and non-Hispanic White and Black adolescent females could achieve it within 2 years. Hispanic and total non-Hispanic adolescent females have achieved the benchmark.

Slide 50

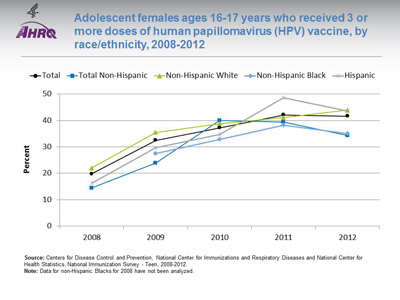

Adolescent females ages 16-17 years who received 3 or more doses of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine, by race/ethnicity, 2008-2012

Image: Graph shows adolescent females ages 16-17 years who received 3 or more doses of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine:

| Race / Ethnicity | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 19.8 | 32.5 | 37.2 | 42.1 | 41.6 |

| Total Non-Hispanic | 14.4 | 23.9 | 40.0 | 39.4 | 34.3 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 27.4 | 32.8 | 38.2 | 35.0 | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 22.0 | 35.5 | 38.8 | 41.1 | 43.9 |

| Hispanic | 16.3 | 29.7 | 34.7 | 48.6 | 43.5 |

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Immunizations and Respiratory Diseases and National Center for Health Statistics, National Immunization Survey—Teen, 2008-2012.

Note: Data for non-Hispanic Blacks for 2008 have not been analyzed.

- Overall Rate: In 2012, the percentage of adolescent females ages 16-17 years who received 3 or more doses of HPV vaccine was 41.6%.

- Trends:

- From 2008 to 2012, the total percentage of adolescent females ages 16-17 years who received 3 or more doses of HPV vaccine improved from 19.8% to 41.6%.

- From 2008 to 2012, the percentage of adolescent females ages 16-17 years who received 3 or more doses of HPV vaccine improved for Whites (from 22% to 43.9%), Hispanics (from 16.3% to 43.5%), and total non-Hispanic (from 14.4% to 34.3%).

Slide 51

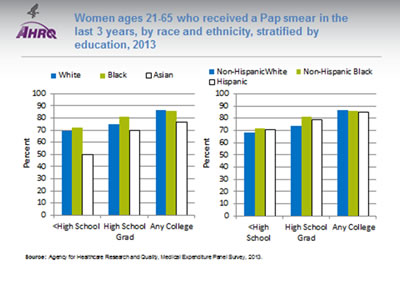

Women ages 21-65 who received a Pap smear in the last 3 years, by race and ethnicity, stratified by education, 2013

Image: Charts show women ages 21-65 who received a Pap smear in the last 3 years:

Left Chart (Race):

| Education | White | Black | Asian |

|---|---|---|---|

| <High School | 69.5 | 72.2 | 49.8 |

| High School Grad | 74.7 | 81 | 70.1 |

| Any College | 86.5 | 86.1 | 76.3 |

Right Chart (Ethnicity):

| Education | Non-Hispanic White | Non-Hispanic Black | Hispanic |

|---|---|---|---|

| <High School | 68.1 | 71.7 | 70.6 |

| High School Grad | 74.0 | 81.4 | 79.0 |

| Any College | 86.8 | 86.1 | 85.0 |

Source: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2013

- Importance:

- Screening aims to identify high-grade precancerous cervical lesions to prevent development of cervical cancer and early-stage asymptomatic invasive cervical cancer. Early-stage cervical cancer may be treated with surgery (hysterectomy) or chemoradiation. The treatment of precancerous rather than early-stage cancerous lesions is unique to cervical cancer and is the foundation of the success of cervical cancer screening. Treatment of precancerous lesions is less invasive than treatment of cancer and results in fewer adverse effects (U.S. Preventive Services Task Force).

- Another important way for women to receive recommended cervical cancer screening is through federally supported community health centers (CHCs), which provide comprehensive primary care services, regardless of ability to pay, helping reduce disparities and improve access of vulnerable populations. Even though CHCs tend to serve low-income and mostly uninsured or publicly insured populations, the rates of recommended screenings among women seen at CHCs are similar to the national averages of all women. In 2009, 85.2% of female CHC patients reported receiving the recommended cervical cancer screening compared with 81.2% of all U.S women (Women's Health USA, 2013).

- Overall Rate: In 2013, the percentage of women ages 21-65 who received a Pap smear in the last 3 years was 80.7% (data not shown).

- Groups With Disparities:

- In 2013, Asian women were less likely than White women to receive a Pap smear in the last 3 years regardless of educational level. About half of Asian women with less than a high school education (49.8%) received a Pap smear compared with 69.5% of White women. For those with any college, the percentages were 76.3% for Asian women and 86.5% for White women.

- Black women with a high school education and less than a high school education were more likely than White women to receive a Pap smear in the last 3 years.

- In 2013, Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black women with a high school education and less than a high school education were more likely than non-Hispanic White women to receive a Pap smear in the last 3 years. Among high school graduates, the percentages were 81.4% among non-Hispanic Black women and 74% among non-Hispanic White women.

Slide 52

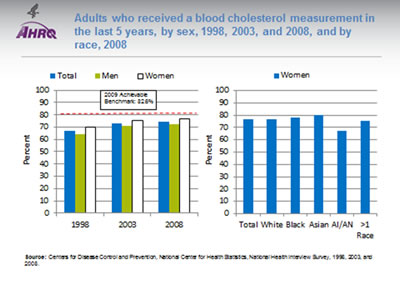

Adults who received a blood cholesterol measurement in the last 5 years, by sex, 1998, 2003, and 2008, and by race, 2008

Image: Charts show adults who received a blood cholesterol measurement in the last 5 years:

Left Chart:

| Sex | 1998 | 2003 | 2008 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 67 | 73.2 | 74.6 |

| Men | 64.2 | 71.0 | 72.2 |

| Women | 69.7 | 75.3 | 76.9 |

2009 Achievable Benchmark: 82.6%.

Right Chart (Women by Race/Ethnicity):

- Total - 76.9%.

- White - 76.5%.

- Black - 77.9%.

- Asian - 80.0%.

- AI/AN - 67.3%.

- More than 1 Race - 75.0%.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Health Interview Survey, 1998, 2003, and 2008.

- Importance: Early detection and treatment of high blood cholesterol can prevent heart disease and stroke. Because high cholesterol levels typically cause no symptoms, screening is essential.

- Overall Rate: In 2008, the total percentage of adults who received a blood cholesterol measurement in the last 5 years was 74.6%. In 2008, the total percentage of women who received a blood cholesterol measurement in the last 5 years was 76.9%.

- Groups With Disparities:

- In all years, women were more likely to receive a blood cholesterol measurement compared with men.

- In 2008, there were no statistically significant differences by race among women who received a blood cholesterol measurement: Whites (76.5%), Blacks (77.9%), Asians (80%), AI/ANs (67.3%), and more than 1 race (75%).

- Achievable Benchmark:

- The 2009 top 5 State achievable benchmark was 82.6%. The top 5 States that contributed to the achievable benchmark are District of Columbia, Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, and Rhode Island.

- At the current rate of change, the total population could achieve the benchmark in 11 years, men in 13 years, and women in 8 years.

Slide 53

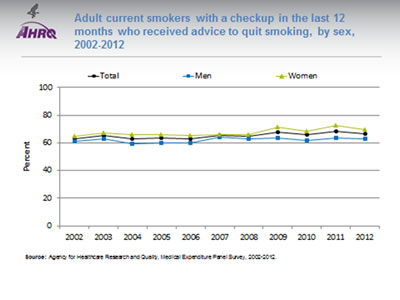

Adult current smokers with a checkup in the last 12 months who received advice to quit smoking, by sex, 2002-2012

Image: Graph shows adult current smokers with a checkup in the last 12 months who received advice to quit smoking:

| Sex | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 63.1 | 65.3 | 63.1 | 63.4 | 62.7 | 65.1 | 64.5 | 67.6 | 65.7 | 68.2 | 66.5 |

| Men | 61.4 | 63.0 | 59.7 | 60.0 | 59.7 | 64.0 | 62.9 | 63.3 | 62.0 | 63.4 | 63.2 |

| Women | 64.5 | 67.2 | 65.7 | 66.2 | 65.1 | 66.1 | 65.8 | 71.3 | 68.6 | 72.8 | 69.6 |

Source: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2002-2012.

- Importance: Smoking is a modifiable risk factor, and health care providers can help encourage patients to change their behavior and quit smoking. The 2008 update of the Public Health Service Clinical Practice Guideline, Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence, concludes that counseling and medication are both effective tools alone, but the combination of the two methods is more effective in increasing smoking cessation. For more information: http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/clinicians-providers/guidelines-recommendations/tobacco/index.html.

- Overall Rate: In 2012, the percentage of adult current smokers with a checkup in the last 12 months who received advice to quit smoking was 66.5%.

- Trends: From 2002 to 2012, the percentage of adult current smokers with a checkup in the last 12 months who received advice to quit smoking improved overall (from 63.1% to 66.5%) and for women (from 64.5% to 69.6%).

- Groups With Disparities:

- In 7 of 11 years, female adult current smokers with a checkup were more likely to receive advice to quit smoking compared with male adult current smokers.

- In 2012, female adult current smokers (69.6%) with a checkup were more likely to receive advice to quit smoking compared with male adult current smokers (63.2%).

Slide 54

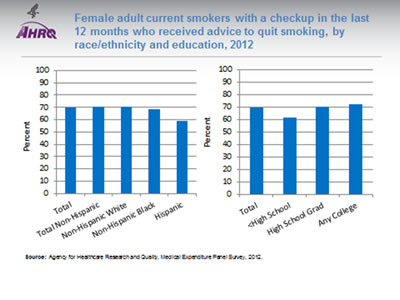

Female adult current smokers with a checkup in the last 12 months who received advice to quit smoking, by race/ethnicity and education, 2012

Image: Charts show female adult current smokers with a checkup in the last 12 months who received advice to quit smoking:

Left Chart (Race/Ethnicity):

- Total - 69.6%.

- Total Non-Hispanic - 70.4%.

- Non-Hispanic White - 70.7%.

- Non-Hispanic Black - 68.8%

- Hispanic - 58.9 %.

Right Chart (Education):

- Total - 69.6%.

- Less than High School - 61.7%.

- High School Grad - 70.0%.

- Any College - 72.6%.

Source: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2012.

- Overall Rate: In 2012, the percentage of female adult current smokers with a checkup in the last 12 months who received advice to quit smoking was 69.6%.

- Groups With Disparities:

- In 2012, Hispanic female adult current smokers (58.9%) with a checkup were less likely to receive advice to quit smoking compared with non-Hispanic White female adult current smokers (70.7%).

- In 2012, female adult current smokers with a checkup with less than a high school education (61.7%) were less likely to receive advice to quit smoking compared with those with any college (72.6%).

Affordability

Slide 55

Chartbook on Women's Health Care

Affordability

Slide 56

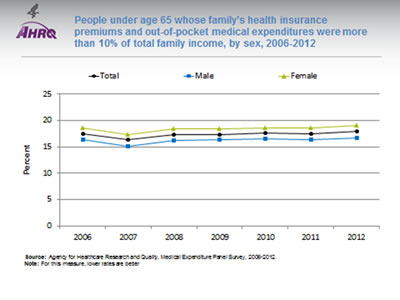

People under age 65 whose family's health insurance premiums and out-of-pocket medical expenditures were more than 10% of total family income, by sex, 2006-2012

Image: Graph shows people under age 65 whose family's health insurance premiums and out-of-pocket medical expenditures were more than 10% of total family income:

| Sex | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 17.5 | 16.3 | 17.3 | 17.4 | 17.6 | 17.5 | 17.9 |

| Male | 16.3 | 15.2 | 16.2 | 16.4 | 16.5 | 16.4 | 16.7 |

| Female | 18.6 | 17.4 | 18.4 | 18.4 | 18.7 | 18.5 | 19.1 |

Source: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2006-2012.

Note: For this measure, lower rates are better

- Importance: Health care expenses that exceed 10% of family income are a marker of financial burden for families. Chevan and colleagues (2015) found that being female was one of the factors that increased the odds of out-of-pocket expenditures for physical therapy services.

- Overall Rate: In 2012, the total percentage of people with out-of-pocket expenditures greater than 10% of income was 17.9%.

- Trends: From 2006 to 2012, there were no statistically significant changes among the total population or among males and females.

- Groups With Disparities:

- In all years from 2006 to 2012, the percentage of people with out-of-pocket expenditures greater than 10% of income was higher for females than for males.

- In 2012, females (19.1%) were more likely to have health insurance premiums and out-of-pocket medical expenditures more than 10% of total family income compared with males (16.7%).

Slide 57

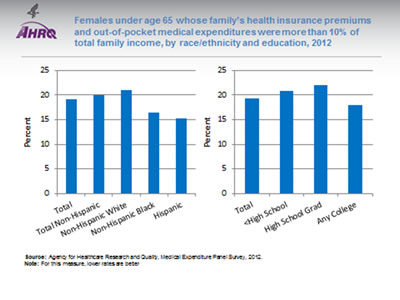

Females under age 65 whose family's health insurance premiums and out-of-pocket medical expenditures were more than 10% of total family income, by race/ethnicity and education, 2012

Image: Charts show females under age 65 whose family's health insurance premiums and out-of-pocket medical expenditures were more than 10% of total family income:

By race/ethnicity:

- Total - 19.1%.

- Total Non-Hispanic - 20.0%.

- Non-Hispanic White - 21.1%.

- Non-Hispanic Black - 16.5%.

- Hispanic - 15.3%.

By education:

- Total - 19.3%.

- Less than High School - 20.8%.

- High School Grad - 22.0%.

- Any College - 18.0%.

Source: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2012.

Note: For this measure, lower rates are better.

- Overall Rate: In 2012, 19% of females had health insurance premiums and out-of-pocket medical expenditures that were more than 10% of total family income.

- Groups With Disparities:

- In 2012, non-Hispanic Black (16.5%) and Hispanic females (15.3%) were less likely to have health insurance premiums and out-of-pocket medical expenditures that were more than 10% of total family income compared with non-Hispanic White females (21.1%).

- Women with less than a high school education (20.8%) and a high school education (22%) were more likely to have health insurance premiums and out-of-pocket expenditures that were more than 10% of total family income compared with women with any college (18%).

Slide 58

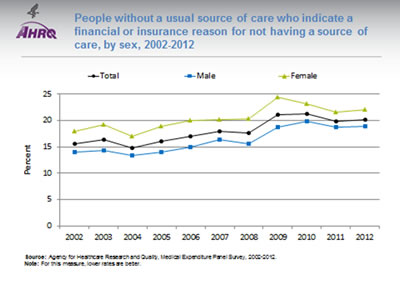

People without a usual source of care who indicate a financial or insurance reason for not having a source of care, by sex, 2002-2012

Image: Graph shows people without a usual source of care who indicate a financial or insurance reason for not having a source of care:

| Sex | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 15.6 | 16.3 | 14.8 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 17.6 | 21.1 | 21.2 | 19.9 | 20.2 |

| Male | 13.9 | 14.3 | 13.4 | 14.0 | 14.9 | 16.4 | 15.6 | 18.8 | 19.8 | 18.7 | 19.0 |

| Female | 18.0 | 19.2 | 17.0 | 19.0 | 20.0 | 20.2 | 20.3 | 24.4 | 23.2 | 21.6 | 22.0 |

Source: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2002-2012.

Note: For this measure, lower rates are better.

- Importance: High-quality health care is facilitated by having a regular provider, but some Americans may not be able to afford one. It is estimated that women without a usual source of care do not receive recommended cancer screening (Sabatino, et al., 2015). Predictors for not having a usual source of care include lack of insurance, less educational attainment, and low income.

- Overall Rate: In 2012, 20.2% of people without a usual source of care indicated a financial or insurance reason for not having a source of care.

- Trends:

- From 2002 to 2012, the percentage of people without a usual source of care who indicated a financial or insurance reason for not having a source of care worsened overall (from 15.6% to 20.2%) and for both sexes (from 13.9% to 19% for males and from 18% to 22% for females).

- Groups With Disparities:

- From 2002 to 2012, females were more likely to be without a usual source of care and indicate a financial or insurance reason for not having a source of care than their male counterparts.

- In 2012, females (22%) were more likely to be without a usual source of care and indicate a financial or insurance reason for not having a source of care than males (19%).

Slide 59

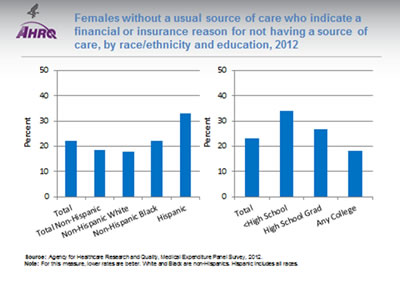

Females without a usual source of care who indicate a financial or insurance reason for not having a source of care, by race/ethnicity and education, 2012

Image: Charts show females without a usual source of care who indicate a financial or insurance reason for not having a source of care:

By race/ethnicity:

- Total - 22.0%.

- Total Non-Hispanic - 18.6%.

- Non-Hispanic White - 18.0%.

- Non-Hispanic Black - 22.3%.

- Hispanic - 33.0%.

By education:

- Total - 23.3%.

- Less than High School - 34.1%.

- High School Grad - 26.7%.

- Any College - 18.2%.

Source: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2012.

Note: For this measure, lower rates are better. White and Black are non-Hispanics. Hispanic includes all races.

- Overall Rate: In 2012, 22% of females without a usual source of care indicated a financial or insurance reason for not having a source of care.

- Groups With Disparities:

- In 2012, Hispanic females (33%) without a usual source of care were more likely to indicate a financial or insurance reason for not having a usual source of care compared with non-Hispanic White females (18%).

- Hispanic females were the group with the highest percentage of people without a usual source of care due to finances or insurance.

- In 2012, women without a usual source of care with less than a high school education (34.1%) and those with a high school education (26.7%) were more likely to indicate a financial or insurance reason for not having a source of care compared with those with any college (18.2%).

Slide 60

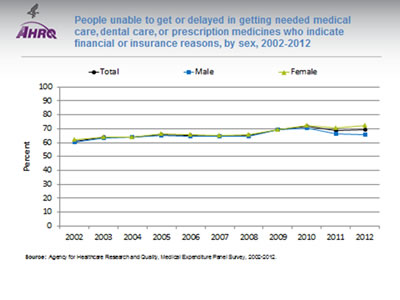

People unable to get or delayed in getting needed medical care, dental care, or prescription medicines who indicate financial or insurance reasons, by sex, 2002-2012

Image: Graph shows people unable to get or delayed in getting needed medical care, dental care, or prescription medicines who indicate financial or insurance reasons:

| Sex | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 61.2 | 63.7 | 63.8 | 65.6 | 65.2 | 64.6 | 65.2 | 69.2 | 71.4 | 68.7 | 69.3 |

| Male | 60.2 | 63.2 | 64.1 | 64.9 | 64.6 | 64.2 | 64.3 | 69.0 | 70.6 | 66.2 | 65.5 |

| Female | 62.0 | 64.0 | 63.6 | 66.1 | 65.7 | 64.8 | 65.9 | 69.3 | 72.0 | 70.5 | 72.3 |

Source: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2002-2012.

- Importance: Some Americans cannot afford all the care they need. Therefore, many delay getting needed health care, which could exacerbate health conditions. Unaffordable health care has been cited as a significant factor precluding women veterans from obtaining needed medical care (Washington, et al., 2011).

- Overall Rate: In 2012, among people who were unable to get or delayed getting needed medical care, dental care, or prescription medicines, 69.3% indicated financial or insurance reasons.

- Trends:

- From 2002 to 2010, among people unable to get or delayed in getting needed medical care, the percentage who cited financial or insurance reasons increased, but by 2011 the percentage decreased.

- From 2002 to 2012, the percentage worsened for females (from 62% to 72.3%) and for the total population (from 61.2% to 69.3%).

- Groups With Disparities: In 2012, the percentage of females unable to get or delayed in getting health care who indicated financial or insurance reasons was higher than for males. Among those who were unable to get or delayed in getting needed care, approximately 72% of females cited financial or insurance reasons compared with 65.5% of males.

Slide 61

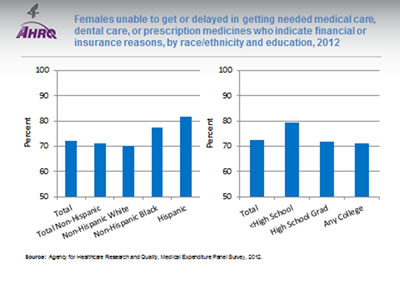

Females unable to get or delayed in getting needed medical care, dental care, or prescription medicines who indicate financial or insurance reasons, by race/ethnicity and education, 2012