A basic understanding of CLT is required to understand how cognitive load impacts clinicians and healthcare systems. CLT was first developed in the 1980s and focused on human information processing, memory, and problem solving within education.14 Importantly, CLT did not attempt to directly measure cognitive load, but rather described a theoretical lens with which to view human learning.15

Since then, there has been growing awareness that CLT provides a useful framework beyond the educational sphere and that key concepts can be applied to diagnostic reasoning.16 Cognitive load has two key domains composed of types of memory and types of cognitive load, which are discussed below.

Types of Memory

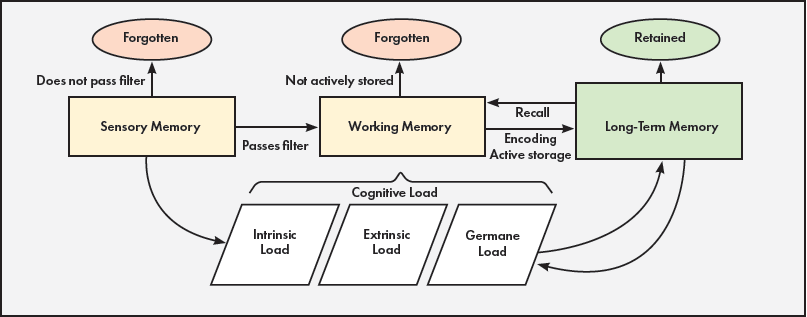

The first key CLT domain describes types of memory. Memory is the neurochemical and psychological process linked to information processing, encompassing tasks such as encoding, storage, and subsequent recall.17 Memory, as it applies to CLT, can be broken into three subcomponents: sensory, working, and long-term memory.

Sensory memory allows sensory input to be filtered and, if relevant, passed on to working memory. Sensory memory has huge capacity, but information exists for mere seconds before being forgotten or passed on (e.g., continuous processing of all visual, auditory, tactile, gustatory, and olfactory input with transient conscious awareness of only relevant stimuli, such as an alarm).10

Working memory contains actively processed information and executes intentional cognitive tasks. Working memory can hold five to nine pieces of information at the same time and critically analyze around four pieces of this information.18 Unless effort is taken to transform these pieces of information into long-term memory, working memories will be lost within 1 minute (e.g., being told an unusual medication dose by a pharmacist and placing the order, without being able to later remember the dosing amount).

Finally, long-term memory is the theoretically infinite memory space that can store cognitive schemas and facts for subsequent recall (e.g., intentional memorization of a diagnostic approach to anemia).10

Types of Cognitive Load

The second key CLT domain describes types of cognitive load. Cognitive load is the amount of information stored in working memory at any one time and can be broken into three subcomponents: intrinsic, extrinsic, and germane load. Intrinsic load is information critical for the task (e.g., effort required to learn a new task, process relevant clinical information, or perform procedural steps).

Extrinsic load is information present but detrimental to the task. It can include information presented in an ineffectual way (e.g., overly complicated electronic record visuals). It may also include load from the external environment (e.g., chaotic surrounding environment) or load from the internal environment (e.g., stress from a recent negative patient interaction).

Germane load is the load imposed by deliberate use of cognitive strategies for long-term memory formation and learning (e.g., diagnostic schemas and procedural automation).13,19 Figure 1 shows the interplay between types of memory and cognitive load.

Figure 1. Conceptual map of cognitive load theory key domains

Clinical Example

Consider the following scenario to better understand how CLT might apply to a clinician as they perform diagnostic reasoning.

A hospitalist is admitting a patient with presumed new heart failure from a busy emergency department. As the hospitalist enters the patient’s room, various types of memory become relevant. They begin to unconsciously process relevant and irrelevant sensory information; they note the room number and patient’s voice and face, while filtering out sirens from outside, telemetry beeps, and chaos from the code occurring across the hall. They also begin to recall from their long-term memory the pathophysiology of congestive heart failure. All relevant information from both sensory and long-term memory is brought into their working memory but, based on working memory constraints, they can only critically analyze and apply around four of these memories at a time.18

The hospitalist is also simultaneously handling various types of cognitive load. They manage intrinsic cognitive load demands as they assess for elevated jugular venous pressure, analyze the electrocardiogram, and ask the patient about symptoms of volume overload. They manage extrinsic cognitive load as they concurrently process unrelated “best practice alerts” from the electronic health record (EHR), messages from nurses about other patients, and stress from worrying about a sick family member. Finally, they use germane cognitive load to pull in congestive heart failure diagnostic schemas to compare this patient’s clinical presentation with their typical representation of a patient with heart failure.

When you consider all the cognitive processes that must occur with reasonable precision during the diagnostic reasoning process to accurately diagnose this patient with decompensated heart failure, the complexity of cognition needed for this relatively simple clinical task becomes clear.