Change Ideas to Improve Target Measure Performance

Table 2 below provides change idea details, resources, and tools associated with the secondary drivers presented above in the key driver diagrams. These change ideas provide actionable pathways to support QI activities aimed at improving target measure performance in the safe and judicious use of antipsychotic medications in children and adolescents. The table is organized at the level of implementation (e.g., plan, plan/practice, youth/family) indicated in the key driver diagrams and then grouped by secondary driver.

Table 2. Change Ideas to Improve Target Measure Performance

| Change Idea | Details and Resources | Secondary Driver |

|---|---|---|

| Plan Level | ||

| Webpage Updates | Update webpages to reflect network changes. | Offer resources to facilitate youth and families in accessing services. |

| Patient Navigation |

Provide navigation resources to improve access and linkage.

|

|

| Improve Communication via Technology |

Facilitate communication with youth through new technology.

|

|

| Care Management |

Use care managers to help ensure access to psychosocial care. Allocate health plan staff to facilitate connecting youth and families to available resources (e.g., in-network providers with availability.)

|

|

| Monitor Access and Waiting Lists |

|

Develop processes to monitor network adequacy for pediatric mental health services, including access to evidence-based psychotherapeutic interventions and psychiatry. |

| Monitor Urgent/ Emergency Access |

Assess access to urgent and emergency mental health services for children and adolescents, especially for higher risk individuals.

|

|

| Prior-Authorization Programs |

Adopt prior-authorization programs.

|

Implement pharmacy policies and programs that foster appropriate prescribing (e.g., pharmacy edits). |

| Pharmacy Review Panels |

Use pharmacy review panels to determine appropriateness of prescribed medications.

|

|

| Plan/Practice Level | ||

| Guidelines/ Treatment Recommendations |

Use persuasive educational materials on current guidelines and treatment recommendations to educate clinicians, including resources for monitoring metabolic side effects.

Antipsychotics Prescribing in Children:

Metabolic Monitoring:

|

Provide education to clinicians, including both antipsychotics prescribers and pediatric medical care providers. |

| Toolkits/Care Pathways |

Use toolkits and care pathways to clearly guide clinician action in-line with practice guidelines and treatment recommendations, including youth without a primary indication for antipsychotics. General Mental Health:

Specific to Antipsychotics Prescribing:

|

Provide education to clinicians, including both antipsychotics prescribers and pediatric medical care providers. |

| Risks/Side Effects Factsheets |

Use factsheets to educate clinicians on risks and side effects of treatment with antipsychotics.

|

|

| Train Clinicians on Youth/Family Engagement |

Provide training to clinicians on engaging youth and family in shared-decision making to understand treatment options and associated pros and cons.

|

|

| Family Training Materials |

Provide training and materials to help clinicians educate and support families in understanding the need for metabolic monitoring.

|

|

| Web Trainings | Provide web-based training to clinicians. | |

| Data Monitoring Tools |

Use data monitoring tools to monitor provider performance.

|

Monitor provider performance on the measure and provide feedback to providers. |

| Care Gap Reports | Use care gap reports to feed information back to providers (e.g., primary care physicians, psychiatrists). Care gap reports can also be used to highlight a provider’s current performance compared to others. | |

| Incentive | Establish incentive programs to help match targets. | |

| Data Exchange | Create data exchanges with key partners (e.g., hospitals). | |

| Academic Detailing |

Implement academic detailing and/or peer-to-peer education interventions with select prescribers (based on performance or volume) to improve prescribing practices. This provides clinicians with access to expert consultation and case reviews.

|

Ensure alignment with evidence-based practice. Target select prescribers based on performance or volume. |

| Knowledge/ Beliefs Assessment | Assess clinician knowledge and beliefs. | |

| Psychosocial Services Assessment | Assess psychosocial services for management of conditions for which multiple concurrent antipsychotic medications are being prescribed. | |

| Standing Lab Orders | Align policies and reimbursement for standing lab orders. | Develop efficient internal processes to encourage appropriate lab testing. |

| Reimbursement for Lab Tests | Allow reimbursement for labs drawn in behavioral health settings. | |

| Pharmacist Integration | Integrate pharmacists in the process for identifying the need for lab testing. | |

| Prescription Notification to Provider | Send notifications to clinicians when antipsychotics are first prescribed. | Improve coordination and communication between the plan and behavioral health and primary care providers. |

| Care Gap Reminders | Send care gap reminders to clinicians who may not be aware a patient needs a recommended service (e.g., primary care providers may not be aware that a patient was prescribed an antipsychotic by a psychiatrist and therefore needs metabolic monitoring). | |

| EHR Enhancements |

Enhance electronic health records (EHR) to support metabolic monitoring through flags or reminders.

|

|

| Youth/Family Level | ||

| Family/ Youth Organizations | Make connections with family and youth run organizations to provide linkages to peer support opportunities. | Increase access to resources and capacity to engage in services. |

| Family Training Incentives |

Support and incentivize participation in family training.

|

|

| Foster Care Coordination |

Coordinate with state and local foster care agencies to identify needs and provide additional supports and incentives for foster parents to engage in services.

|

|

| Medication Management Education |

Provide education to youth and families on medication management, including the metabolic impacts of medications. Offer training in evidence-based practices for youth, parents/ guardians, and families (youth with their parents/guardians).

|

Provide education to youth and families via case management. |

| Monitoring Tools | Provide self-management/monitoring tools for youth and families to use (e.g., charting the frequency of metabolic monitoring, observing warning signs, etc.). | |

| Team Engagement | Engage key internal teams (e.g., case management) to lead outreach efforts. | |

| Informed Consent Policies/ Education |

Implement policies and provide educational materials on informed consent for youth and families.

|

|

Quality Improvement in Action: The NCINQ Antipsychotics in Children Learning Collaborative

From August 2017 to December 2018, NCINQ led a quality improvement (QI) learning collaborative with five New York-based Medicaid health plans. Participants in the collaborative used data gathered through national Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) reporting and the Medicaid Child Core Set to examine performance and improvement on several quality measures that address the use of antipsychotics in children and adolescents. The plans in this collaborative convened for two in-person meetings, bi-monthly webinars, monthly individual calls, and office hours as needed.

Plans that participated in the collaborative used and tested the key drivers and change ideas presented in this toolkit.ii Case studies and examples from the collaborative are highlighted below and in the section on QI Best Practices for the Safe and Judicious Use of Antipsychotic in Children and Adolescents. Plans also tested strategies to engage youth and family in their QI work. For additional information, strategies, and resources on engaging youth and family to support QI work, please see the standalone toolkit: Youth and Family Engagement in Quality Improvement.

The sections below describe measure-specific performance benchmarks, improvement strategies implemented by the participating plans, and performance results from the collaborative. Information on considerations for selecting appropriate improvement targets is also presented, as well as a summary of the contextual factors found to facilitate progress, key components of successful strategies, and identified challenges and barriers to improvement.

____________________

ii. The strategies included in this toolkit were implemented prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and may need to be adapted to account for changes in care access and delivery during the pandemic.

Considerations for Selecting Appropriate Improvement Targets

To identify benchmarks that could be used to set improvement goals for each measure and to subsequently monitor performance during the course of the collaborative, the team undertook the following activities in a stepwise fashion:

- Reviewed the HEDIS national performance benchmarks as well as the NY state benchmarks (see tables below in each measure-specific section for details).

- Conducted an “improvement analysis” using 2015 and 2016 HEDIS reporting data to calculate the amount of improvement at the plan level seen year to year. “High improving” plans were defined as those that exhibited improvement rates between 2015 and 2016 in the top 25th percentile.

- Worked individually with the plans participating in the collaborative to compare baseline performance rates to the national and state benchmarks, as well as the findings from the “improvement analysis.”

- Coached plans to track the amount of improvement by comparing current performance rates with where the performance was at one year prior (i.e., internal benchmarking).

Most plans selected modest improvement targets for the Psychosocial Care and Metabolic Monitoring measures, equating to around a 10% increase in performance rates compared to baseline. The Multiple Concurrent Antipsychotics measure performance was already very good for most plans with little room for improvement. Two plans chose to implement focused strategies for improvement that targeted this measure; however, only one of the plans was able to realize an improvement in performance.

Use of First-Line Psychosocial Care for Children and Adolescents on Antipsychotics

Table 3 below provides HEDIS performance benchmarks at the national and NY state levels for the Medicaid product line for the Psychosocial Care measure from 2016 through 2019. Voluntary state reporting data for this measure is available for federal fiscal year 2018 is available in the Medicaid Child Core Set.

Table 3. Medicaid Performance Benchmarks, First-Line Psychosocial Care

| Year | Level of Analysis | N of Entities | Mean Performance | SD | Percentile | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10th | 25th | 50th | 75th | 90th | |||||

| 2016 | Health Plan - National | 134 | 60.2 | 13.3 | 43.9 | 53.8 | 61.8 | 68.2 | 74.2 |

| Health Plan - NY State | 15 | 65.7 | 7.25 | 54.6 | 60.0 | 66.9 | 71.1 | 74.2 | |

| 2017 | Health Plan - National | 137 | 59.6 | 13.4 | 45.9 | 53.0 | 61.4 | 67.7 | 72.7 |

| Health Plan - NY State | 15 | 68.9 | 8.2 | 57.4 | 62.5 | 68.9 | 72.3 | 82.0 | |

| 2018 | Health Plan - National | 139 | 57.6 | 15.5 | 36.4 | 52.7 | 60.6 | 66.6 | 75.0 |

| Health Plan - NY State | 15 | 64.5 | 6.7 | 52.1 | 59.7 | 65.9 | 69.0 | 71.1 | |

| 2019 | Health Plan - National | 148 | 61.9 | 15.3 | 42.0 | 53.7 | 64.8 | 72.5 | 79.4 |

| Health Plan - NY State | 15 | 73.8 | 11.2 | 67.4 | 68.9 | 76.4 | 79.4 | 80.5 | |

Specific strategies implemented and tested during the collaborative to improve first-line psychosocial care in children and adolescents are included in Table 4 below. References to case study examples are provided when applicable and notable lessons learned specific to a particular strategy are presented where relevant. Strategies were implemented at the plan level.

Table 4. First-Line Psychosocial Care Improvement Strategies

| Strategy | Description |

|---|---|

| Pharmacy Edit: Prior-Authorization | One plan tested a requirement for providers to: 1) submit prior authorizations to newly dispense an antipsychotic medication; and 2) confirm psychosocial care had first been received (Case Study 1). |

| Provider Outreach and Education | One plan leveraged existing relationships (via Senior Leadership) with a large provider group to: 1) understand missed opportunities for delivering psychosocial care; and 2) work to improve access and compliance (Case Study 2).

Key Learning: Focused education and outreach to prescribers (e.g., psychiatrists) was more effective when led by medical directors versus QI team members. |

| Member Outreach and Education | Multiple plans used care managers, social workers, and/or community partners to assess whether members had psychosocial care and/or needed help connecting to services. In addition, one plan developed predictive reports based on claims data to: 1) identify youth who might be soon prescribed antipsychotics; and 2) target them for a case management intervention to address any barriers to obtaining psychosocial care. |

| Strategic Use of PSYCKES Database for Data Reconciliation | One plan utilized PSYCKES and medical record data collection to identify when youth were receiving psychosocial care that was not represented in claims data. This helped the plan determine more accurate rates for the Psychosocial Care measure. Once the data was reconciled, the plan sent alerts to providers for non-compliant members. |

Case Study 1: Pharmacy Edit

Plan A successfully implemented pharmacy “soft edits” to discourage inappropriate prescribing of antipsychotic medications to youth. One of these edits included the implementation of a prior authorization component that required providers to document that a child had first received a trial of psychosocial care before being prescribed an antipsychotic. Plan A’s successful implementation of this edit was in large part due to on-site expertise and oversight by a Senior Pharmacy Consultant. This consultant, along with the full QI team and an engaged Senior Behavioral Health and Medical Leadership team, helped to design the pharmacy edit, proactively address anticipated challenges, identify data the team needed to assess the impact, and review outcome reports. In addition, Senior Behavioral Health and Medical Leadership allocated dedicated resources to QI efforts, further facilitating the success of this improvement strategy. When Plan A implemented the pharmacy edit in February 2018, performance was at 54.3%. By the end of October 2019, performance increased to 66.9%.

Case Study 2: Provider Outreach And Engaged Leadership

Plan B conducted ongoing provider outreach with a key target site to better understand missed opportunities to provide first-line psychosocial care to indicated youth and adolescents. Outreach focused on identifying providers with members who may not have been triaged for a psychosocial assessment. The QI team and clinical staff subsequently met with these providers to conduct medical record reviews, explore whether assessments were missed, and if so, identify possible causes. To engage providers, the QI team developed specific discussion scripts to ensure conversations centered on barriers hindering access to psychosocial therapies prior to the engagement of an antipsychotic medication. These conversations also addressed potential compliance improvement tactics. In instances where member access appeared to be an issue, the QI team emphasized the plan’s existing telehealth options. When Plan B implemented this provider outreach campaign in April 2018, performance was at 72.5%. By the end of October 2019, performance increased to 75.8%.

Of note, Plan B saw firsthand how critical engaging leadership is to the success of QI work. For many months, the QI team exerted significant effort to establish contact with this target site, with limited success. Once Plan B engaged their Medical Director, who contacted the Medical Director at the target site, a meeting to discuss the initiative was scheduled immediately. This key connection and partnership was integral in moving the QI work forward.

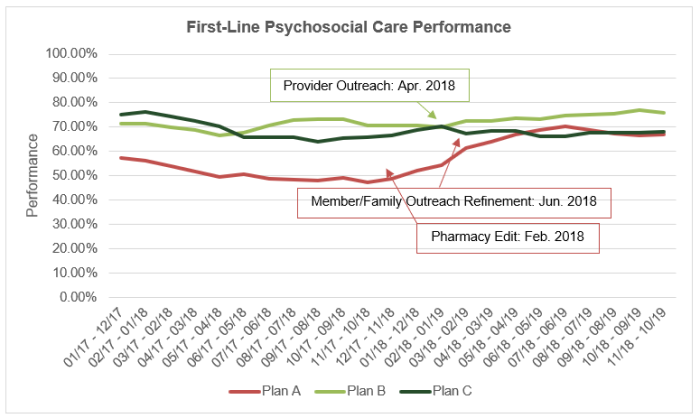

Chart 1. First-Line Psychosocial Care Performance Results for Collaborative Plans that Targeted the Measure for Improvement, 2017-19

The run chart above (Chart 1) provides measure performance data for the three plans in the learning collaborative that implemented strategies to improve performance on the Psychosocial Care measure. The chart has been annotated to identify when particular strategies of note were implemented. For reference and context, the various strategies each plan implemented are noted below, as each plan implemented more than one strategy.

- Plan A: Prior-authorization pharmacy edits (Case Study 1); member and family outreach, including calls from clinical staff to potentially at-risk members to assess whether the member has had psychosocial care, needs to be connected with services, or is experiencing any barriers to receiving care.

- Plan B: Provider outreach and engagement to understand missed assessments and to work to improve access and compliance (Case Study 2); youth empowerment program to provide member programming on mental health treatment options and healthy lifestyle management.

- Plan C: Member and family outreach through the use of care managers and predictive reports to identify at-risk children and adolescents and address barriers to receiving psychosocial care; PSYCKES lookups and medical record data collection to identify psychosocial care not found in claims data; mental health awareness campaign to educate families on antipsychotics.

Metabolic Monitoring for Children and Adolescents on Antipsychotics

Table 5 below provides HEDIS performance benchmarks at the national and NY state levels for the Medicaid product line for the Metabolic Monitoring measure from 2016 through 2019.

Table 5. Medicaid Performance Benchmarks, Metabolic Monitoring

| Year | Level of Analysis | N of Entities | Mean Performance | SD | Percentile | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10th | 25th | 50th | 75th | 90th | |||||

| 2016 | Health Plan - National | 164 | 33.3 | 10.9 | 22.0 | 24.9 | 31.8 | 39.2 | 48.1 |

| Health Plan - NY State | 15 | 40.3 | 8.1 | 25.0 | 36.5 | 41.6 | 48.1 | 48.8 | |

| 2017 | Health Plan - National | 166 | 34.6 | 12.6 | 22.0 | 25.9 | 31.8 | 41.0 | 50.8 |

| Health Plan - NY State | 15 | 41.3 | 7.0 | 31.7 | 36.3 | 42.1 | 46.4 | 50.8 | |

| 2018 | Health Plan - National | 169 | 35.3 | 12.2 | 23.1 | 27.4 | 33.3 | 40.9 | 49.1 |

| Health Plan - NY State | 15 | 42.0 | 6.7 | 33.4 | 34.9 | 43.1 | 47.2 | 50.9 | |

| 2019 | Health Plan - National | 178 | 37.8 | 12.0 | 25.0 | 29.4 | 35.5 | 44.3 | 56.3 |

| Health Plan - NY State | 15 | 42.0 | 7.6 | 33.3 | 37.7 | 41.7 | 47.9 | 51.7 | |

Specific strategies implemented and tested during the collaborative to improve appropriate metabolic monitoring in children and adolescents prescribed an antipsychotic are included in Table 6 below. References to case study examples are provided when applicable and notable lessons learned specific to a particular strategy are presented where relevant. Strategies were implemented at the plan level.

Table 6. Metabolic Monitoring Improvement Strategies

| Strategy | Description |

|---|---|

| Member Outreach | All plans used a combination of internal teams and/or community partners for active outreach to members and families to discuss mental health treatment options and healthy lifestyle engagement. For one plan, the data team pulled at regular intervals a list of members noncompliant for receiving metabolic monitoring, which allowed care managers to then target member education and lab appointment reminders most effectively (Case Study 3). |

| Standing Lab Order | One plan piloted an intervention program with key provider and lab partners to implement standing six-month metabolic screenings for children and adolescents on antipsychotic medications. This strategy included both educational and professional development components. |

| Data Exchange | One plan worked with hospital partners to capture metabolic lab testing data that was not submitted or captured through traditional claims. |

| Provider Outreach | Multiple plans used gap in care reports given to providers to capture members who needed lab testing. In addition, one plan developed a provider relations team that consistently reviewed data to identify providers who had members missing regular metabolic monitoring on their patient panels. The provider relations team subsequently contacted identified providers to supply targeted psychoeducation materials.

Key Learning: Regular face-to-face meetings with clinical and front office staff at practices proved to be most effective in engaging provider teams and serving as opportunities to educate and provide resources. |

| Incentive Program | One plan implemented a member incentive program to encourage Medicaid members identified as needing metabolic monitoring to get the appropriate lab tests by providing a $25 gift card once the tests were completed. This was a short term, five-month effort that helped encourage members to receive guideline recommended care. |

Case Study 3: Member Outreach Campaign Led by Interdepartmental Team

Plan D saw a marked improvement in their metabolic monitoring rates for adolescents from 2017 to 2019 (about 10 percentage points), in part due to a targeted member outreach campaign led by their care management team. An interdepartmental team (including IT, care management, behavioral health, and the plan’s Medical Director) analyzed data on a bi-weekly basis to identify youth who had not received metabolic monitoring. Next steps to close these care gaps included targeted member education outreach, lab appointment reminders, and/or the provision of lab reports from parents. Barriers, such as staff turnover and limited resources in certain departments, were discussed regularly and addressed as needed. Workload was modified on an ongoing basis to facilitate continued progress. Specific workflows and responsibilities for this intervention were mutually determined at team meetings and executed accordingly, further contributing to the success of the intervention.

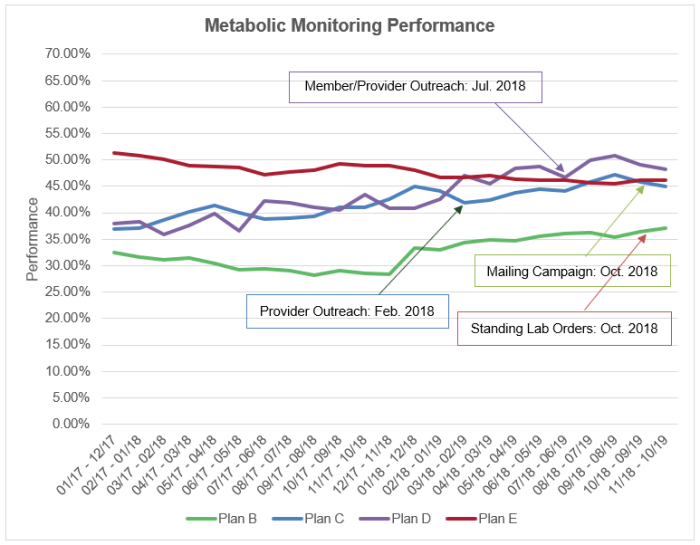

Chart 2. Metabolic Monitoring Performance Results for Collaborative Plans that Targeted the Measure for Improvement, 2017-19

The run chart above (Chart 2) provides measure performance data for the four plans in the learning collaborative that implemented strategies to improve performance on the Metabolic Monitoring measure. The chart has been annotated to identify when improvement strategies were implemented. For reference and context, a complete list of the strategies implemented are included below, since each plan implemented a multi-pronged improvement approach.

- Plan B: Standing lab orders; empowerment program with community partner to host member programming on mental health treatment options and health lifestyle management; incentive program to encourage appropriate metabolic monitoring.

- Plan C: Provider outreach, including care gap reports and discussion; data exchange with hospitals to capture lab test data not captured in claims; member and family education through care management.

- Plan D: Provider outreach and education (Case Study 3); member and family outreach (data team identified members past due on monitoring and case managers targeted these members through education and lab appointment reminders).

- Plan E: Provider outreach and engagement via mailing campaign.

Use of Multiple Concurrent Antipsychotics in Children and Adolescents

Table 7 below provides HEDIS performance benchmarks at the national and NY state levels for the Medicaid product line for the Multiple Concurrent Antipsychotics measure from 2016 through 2018. Voluntary state reporting data for this measure is also available from fiscal year 2016 through 2018 at the Medicaid Child Core Set.

Table 7. Medicaid Performance Benchmarks, Multiple Concurrent Antipsychotics

| Year | Level of Analysis | N of Entities | Mean Performance | SD | Percentile | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10th | 25th | 50th | 75th | 90th | |||||

| 2016 | Health Plan - National | 162 | 2.4 | 1.7 | 0.5 | 1.2 | 2.1 | 3.3 | 4.6 |

| Health Plan - NY State | 15 | 3.5 | 0.8 | 2.6 | 2.8 | 3.3 | 4.0 | 4.6 | |

| 2017 | Health Plan - National | 162 | 2.4 | 1.7 | 0.5 | 1.2 | 2.1 | 3.4 | 4.6 |

| Health Plan - NY State | 15 | 3.4 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 2.2 | 3.5 | 4.6 | 5.0 | |

| 2018 | Health Plan - National | 155 | 2.4 | 1.6 | 0.4 | 1.2 | 2.2 | 3.3 | 4.3 |

| Health Plan - NY State | 15 | 3.6 | 1.2 | 1.9 | 2.7 | 3.5 | 4.7 | 5.0 | |

Specific strategies implemented and tested during the collaborative to improve performance on the Multiple Concurrent Antipsychotics measure are included in Table 8 below. References to case study examples are provided when applicable and notable lessons learned specific to a particular strategy are presented where relevant. Strategies were implemented at the plan level.

Table 8. Multiple Concurrent Antipsychotics Improvement Strategies

| Strategy | Description |

|---|---|

| Pharmacy Edit: Duplicate Therapy | One plan rolled out a pharmacy edit in which the pharmacy automatically rejected dispensing a second antipsychotic medication, identifying it as a “drug utilization error,” when a child had already been prescribed an antipsychotic medication. Pharmacists then had the option to fill the medication (i.e., call the provider to determine why two antipsychotics were prescribed or discuss with the patient at the point of sale). (Case Study 4). |

| Monthly Chart Review and Provider Education | One plan worked with behavioral health partners to: 1) review medical charts of children who have multiple concurrent antipsychotic use to understand their behavioral health diagnoses and utilization; 2) identify the prescribing provider; and 3) conduct provider outreach to understand the rationale for treatment with multiple concurrent antipsychotics in the hopes to encourage deprescribing of the second medication. In this case, continued tracking and trending of measure compliance supported ongoing conversation as to why certain providers continue to have children on multiple antipsychotics and whether/how this can change.

Key Learning: The plan found it challenging to engage providers on this measure given the very small number of youths receiving multiple concurrent antipsychotics. Providers were also resistant to changing the course of treatment for their patients. The plan’s chart review and provider education intervention did not lead to improvement. In fact, the plan’s performance rate worsened over the course of the collaborative.. |

Case Study 4: Pharmacy Edit

Plan A implemented pharmacy “soft edits” to discourage inappropriate prescribing of antipsychotic medications to youth. The first of these edits was introduced in the Fall of 2017 and focused on reducing multiple concurrent antipsychotic use by automatically rejecting prescription fills for a second antipsychotic when a child was already on an antipsychotic. This pharmacy edit impacted measure rates, and Plan A saw a substantial decrease in the rate of children and adolescents on multiple concurrent antipsychotics, indicating performance improvement. When Plan A implemented the pharmacy edit in November 2017, performance was at 5.2%. By the end of October 2019, measure performance improved to 3.6%.

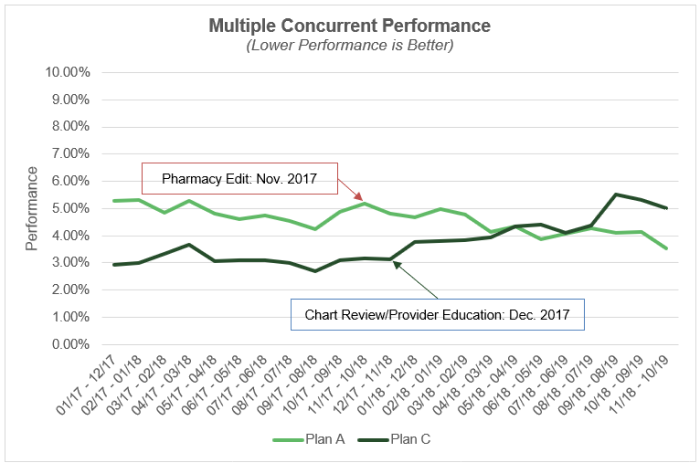

Chart 3. Multiple Concurrent Antipsychotics Performance Results for Collaborative Plans that Targeted the Measure for Improvement, 2017-19

The run chart above (Chart 3) provides measure performance data for the two plans in the learning collaborative that implemented strategies to improve performance on the Metabolic Monitoring measure. The chart has been annotated to identify when improvement strategies were implemented. For reference and context, the strategies implemented by each plan for improvement on this measure are noted below.

- Plan A: Pharmacy edits to reject second prescription when a child or adolescent is already prescribed an antipsychotic medication (Case Study 4).

- Plan C: Monthly chart review and provider education.

Contextual Factors Facilitating Performance Improvement

Throughout the course of the collaborative, the team found that the following contextual factors facilitated performance improvement on the safe and judicious use of antipsychotics in children and adolescents.

- Availability of National HEDIS and State measure performance benchmarks helped plans set improvement goals.

- Alignment of measures across reporting programs allowed the plans to capitalize on data from national, state, plan, and provider levels to target QI efforts. For the NY Quality Assurance Reporting Requirements (QARR)[i], plans are required to use HEDIS specifications, which ensures alignment of data elements and coding across both programs. High levels of reportability and measure utilization stemming from measure alignment contributed to measure uptake and widely available performance results, enabling an examination and comparison of performance rates for NY plans participating in the collaborative, other plans in NY, and plans reporting nationally.

- Running monthly performance rates allowed plans to examine data monthly and compare against the previous year to determine if they were trending toward improvement.

- Having a range of expertise represented on the QI team allowed some plans to implement very specific strategies, such as pharmacy edits, because they had access to the relevant specific expertise (e.g., pharmacy consultant on staff).

- Involvement and buy-in from senior leadership facilitated key provider partner relationships.

Key Components of Successful Strategies

A handful of key components to successful strategies were identified during the collaborative. These key components were not specific to improvement on any specific measure, but rather appeared to have a positive impact regardless of the measure targeted for improvement.

- Using reports to highlight provider performance offered opportunities to educate and deliver resources to providers.

- Focused education and outreach to prescribers (e.g., psychiatrists) was more effective when led by medical directors (i.e., peer-to-peer education) versus QI team members.

- Regular in-person meetings at practice sites with clinical and front office staff at practices proved to be most effective in engaging provider teams and served as opportunities to educate and provide resources to provider teams that supported performance improvement.

Challenges and Barriers to Improvement

Throughout the collaborative, it became apparent that the following items presented challenges to plans when undertaking initiatives to improve performance on the pediatric antipsychotics use measures. To the extent that plans embarking on quality improvement campaigns for the antipsychotics measures can mitigate or control these factors, doing so may increase the likelihood of performance improvement. These challenges were not found to be specific to one particular measure but rather global in nature.

- Given the very small number of youths receiving antipsychotics, plans were met with resistance from providers to engage in QI for these measures. Providers were more focused on quality measures that impacted a greater number of their patients. In particular, the Multiple Concurrent Antipsychotics measure was challenging to engage providers on due to the very small number of youths receiving this therapy.

- There were challenges to coordination of care between behavioral health and physical health providers in settings where there was a lack of behavioral health integration in primary care.

- Due to concerns about sharing mental health information per federal regulations and the stigma associated with behavioral disorders, pediatricians were not always aware of services their patients received elsewhere.

- Plans found it challenging to determine which providers to hold accountable for managing the metabolic side effects of antipsychotics. While antipsychotics were often prescribed by psychiatrists, lab tests to monitor side effects were not typically shared with pediatricians.

- For the Metabolic Monitoring measure, the specifications did not highlight care gaps that existed. Plans found that examining whether children and adolescents received glucose testing and cholesterol testing as two separate rates provided more actionable information. Specifically, when these rates were reported separately, gaps in cholesterol testing became evident, which plans could then target to drive improvements.

Lack of Information on Deprescribing: Even when plans were able to engage providers, there was very little evidence-based guidance available on protocols for deprescribing antipsychotics in children and adolescents that QI teams could provide via provider outreach and education.