Overview

The health care reform law (the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010) focuses on two areas:

- Providing nearly all Americans with insurance.

- Delivery system reform.

The former has received the most media attention, but the latter is equally important. Congress recognized that insuring more people will put more money into the health care system, and that this will be like pouring water into a sieve unless the delivery system is reformed. But what do we need to know about the delivery system to change it in ways that will benefit patients? Where should foundations and funding agencies like the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) focus their efforts?

In this paper I will suggest four key areas of focus for delivery system research. I will begin by offering a definition of delivery system research and its relationship to comparative effectiveness research. I will then present a simple conceptual model of a generic delivery system organization, which will be useful in organizing a "long list" of potential delivery system research topics into broad topic areas. I will then suggest criteria for selecting key areas and propose a short list of key areas for research, including some key questions in each area. I will provide citations for examples of research studies in each of the key areas and will highlight areas in which there is a particular lack of research to date. I will conclude by locating AHRQ's recent American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) Comparative Effectiveness Delivery System Research grants within the analytic scheme presented.

What Is Delivery System Research?

There is no generally accepted definition of delivery system research. I suggest that delivery system research may be broadly defined as research that focuses on organizations which provide health care (such as medical groups, hospitals, long-term care facilities, and home health agencies) and/or on inter-relationships among these organizations. Delivery system research may focus on these organizations' structures and on the processes they use to provide and improve medical care, as well as on relationships among organizations' structures, the processes used, and the cost and quality of care the organizations provide. Delivery system research may also focus on the incentives given to provider organizations by payors (Medicare, Medicaid, and health insurance companies) and regulators and on how these incentives affect organizations' structure, the care processes they use, and the outcomes of care generated by these structures and processes. Incentives are based on measurement of performance, so research that focuses on performance measures should also be considered to be delivery system research.

What is the relationship between delivery system research and comparative effectiveness research (CER)—or, as it is now often called, Patient Centered Outcomes Research? Traditionally, CER compares the effectiveness of drugs, devices, and medical or surgical procedures—traditional CER clearly is not delivery system research, at least not according to the definition suggested in this paper. The findings of traditional CER can only have an impact, however, if they are used by the delivery system, so the delivery system should be a major consumer of CER and a key to the effectiveness of CER.2 In addition, comparative effectiveness research/Patient Centered Outcomes Research focused on the delivery system itself is very important. It is likely that some organizational structures and processes lead to higher quality, lower cost care than others. Delivery system CER is needed to identify these structures and processes (and the incentives that make these structures and processes more likely to be used).

The Federal Coordinating Council for Comparative Effectiveness Research listed "delivery system strategies" as a critically important area in which there is a major lack of CER to date.3 The Institute of Medicine (IOM) Committee on Comparative Effectiveness Research Prioritization stated that delivery system-related research areas were the most commonly listed of the 100 key priorities the Committee selected.4 However, the IOM definition of delivery system-related research was much broader than the definition suggested in this paper—it included what I would define as clinical research, for example, comparing robotic assistance surgery to conventional surgery for common operations, such as prostatectomies. Nevertheless, at least 31 of the 100 IOM priority topics fit the definition of delivery system research suggested here (Appendix A). Twenty-seven of these 31 topics focus on one area of the conceptual model to be presented in the next section of this paper: they focus on processes for improving care to individuals or for improving care for an organization's population of patients. Critically, the IOM emphasized that when the [delivery system] design, intervention, or strategy under study introduced changes that are directly relevant to policy decisions, a comparator may be the status quo.

Conceptual Model

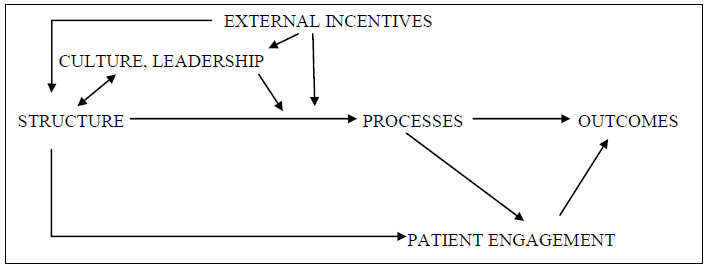

Figure 1 provides a simple model of a generic delivery system organization—it could be a medical group, a hospital, a nursing home facility, etc. The model could also be used for the interface between two delivery system organizations; e.g., what are the structure, culture, external incentives, etc. of the interface between a medical group and a hospital in dealing with inpatient-outpatient transitions? The model can also be used to think about structure-process-outcome relationships for a particular organization or type of organization and/or for a specific disease, such as congestive heart failure. Finally, the model could be used to think about a health care market. For example, what is the structure of the market in McAllen, Texas? How might the culture and leadership of the delivery system in the market be characterized? What processes of care are prevalent in the market, and what are the outcomes of care in the market?

Figure 1. Generic model of an organization and its external incentives

Note: Appendix B gives examples of important structures, external incentives, processes, and outcomes.

External incentives, such as the way the organization is paid (e.g., via fee for service or capitation), antitrust regulation, and pay for performance (P4P) influence the structure that organizations take. For example, global capitation (more accurately, capitation that approached global capitation) in California in the late 1980s and 1990s led to the formation of very large, multispecialty medical groups, to hospital employment of primary care physicians, and to the growth of independent practice associations (IPAs).5-8 Structure no doubt is also influenced by other factors not shown in the model, such as patient and physician preferences and inertia (existing organizations may be slow to disappear or to change their structure, even when incentives change). We have very little understanding of how and why some delivery system organizations develop effective cultures and leadership and others do not, but culture and leadership are likely to be influenced by an organization's structure and the external incentives that it faces.

An organization's structure, culture, and leadership, as well as the external incentives that it faces, shape the processes that the organization implements to provide and improve medical care. For example, a large medical group with strong leadership, a culture of quality improvement, and financial incentives to reduce avoidable hospital admissions (such incentives are currently rare for physicians) is likely to create a nurse care manager program to help patients with congestive heart failure. It is unlikely that such a program would be created by a hospital paid per admission or by a small medical practice with limited resources, relatively few congestive heart failure patients, and no financial incentive to reduce unnecessary admissions.

The model postulates that the processes an organization uses to provide and improve medical care strongly influence outcomes—that is, the total cost of patient care, the quality of care that patients receive, and patient experience. Processes affect outcomes both because of what providers do (e.g., prescribe a medication appropriately) and through their effects on what patients do (i.e., through their effects on patient engagement). Patient engagement is also likely to be affected by the provider organization's structure (e.g., are patients more engaged, generally speaking, when cared for by large vs. small organizations?) and culture (arrow not drawn in the model).

Although all relevant arrows are not shown in the model, it is likely that the organization's structure, culture, and external incentives also influence outcomes directly and not just through their impact on care processes. For example, the culture of some organizations may be that physicians go the extra mile for patients—staying late to see a patient in the office, for example, rather than sending the patient to the emergency department. Structure—for example, the size of a medical group—may directly affect outcomes in many ways. For example, it may be that patients, physicians, and staff know each other better in small practices than in large medical groups, and that this mutual knowledge may lead to a patient with subtle signs (over the telephone) of serious illness being seen by his/her physician quickly in a small practice, whereas in a large group the patient might be triaged to an appointment a few days later or to a same day appointment with a physician other than his or her usual physician.

"Long List" of Delivery System Research Areas and Topics

Appendix C presents a long list of research topics organized by the categories in the conceptual model just discussed; it also suggests sample research questions for each topic. This list of topics is intended to reasonably represent the range of topics that may be considered delivery system research, but no doubt other topics could be added, as well as many additional research questions for each topic.9 Each research area in the list can be studied in the context of: (1) a specific type of delivery system organization; and/or (2) a specific disease or area of preventive care. For each area, key questions are:

- What are alternative forms of the thing in question (e.g., alternative medical group structures or alternative forms of nurse care management for patients with chronic illness)?

- What are the demographics and geographic distribution of the alternative forms (i.e., What is the prevalence of each alternative? Where are these alternatives located? How if at all is the prevalence changing?)?

- What are the factors (e.g., external incentives, regulation) that affect the prevalence of the alternative forms?

- What are the effects, intended and unintended, of alternative forms on the outcomes of care?

Criteria for Selecting Priority Areas for Delivery System Research

The fundamental criterion for selecting priority areas for delivery system research should be: will this research help patients—either directly or by helping providers to provide better care?10 The Federal Coordinating Council for Comparative Effectiveness Research and the IOM Committee on Comparative Effectiveness Research Prioritization developed additional, somewhat more specific criteria for selecting high-priority areas for comparative effectiveness research.3,4 The IOM stressed that the medical conditions studied should have a major impact, either on the population as a whole or on subgroups of patients; that research should include age groups ranging from infancy to the elderly, as well as racial/ethnic minority groups; and that research should seek to fill important gaps in knowledge. The Federal Coordinating Council criteria were similar.

While useful, these criteria are quite broad. I suggest three additional criteria to complement the IOM criteria for the purpose of suggesting key areas for delivery system research:

First, it will be important to have research that focuses on areas of delivery system reform emphasized by the health care reform law (the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act).1 These include new models of organization (Accountable Care Organizations, Patient-Centered Medical Homes, Healthcare Innovation Zones), new models of paying for care (e.g., bundled payments and pay for performance), and public reporting of provider performance.

Second, the best way to improve quality and contain the cost of health care—that is, to increase the value of health care—may be to get physicians, hospitals, and other providers into high-performing organizations and to give them incentives to continually improve care for the population of patients for whom they are responsible.11,12 Thus, more research should focus on

- Identifying the types of organizations that are high performing.

- Identifying the types of incentives that induce these organizations to continually improve care.

- Identifying the types of incentives likely to lead to the creation of more high-performing organizations and to physicians and other providers becoming members of high-performing organizations.

Findings on the types of organizations likely to provide better care could inform decisions about payment and regulatory policies. Additionally, information on the types of organizations likely to provide better care may help patients make better decisions about where to seek care and help physicians and non-physician staff make better decisions about where to work. To the extent that characteristics of high-performing organizations are easily observable—for example, if it turns out that such organizations are large, integrate physicians and a hospital, and/or are multispecialty—these characteristics can be used by patients and physicians to aid their decisions.

The third and final criterion that this paper will suggest for priorities for delivery system research is that this research should routinely evaluate both the intended and the unintended consequences of the structure, process, or incentive being studied. For example, research should ask the following types of questions: (1) What effects, if any, does the structure, process, or incentive have on areas for care not directly related to it? For example, do large organizations score better on typical measures of quality but not on areas of quality that are not typically measured (e.g., timely diagnosis)? Does attention to measured and rewarded areas of quality spill over into improved quality in other areas, or does it lead to reduced quality in other areas? (2) What effects does the structure, process, or incentive have on health care disparities?13 For example, do P4P programs give more bonus money to providers located in economically advantaged areas, thus increasing the resource gap between "rich" and "poor" providers? Do large medical groups provide higher quality care but refuse to treat Medicaid patients?

Suggested Key Areas for Delivery System Research

Even with criteria as specific as those I have just suggested—and I recognize that very different criteria could very plausibly be proposed—there is a lot of room for decisions in selecting key areas for delivery system research. Additionally, as the medical care system changes over time, key areas for study are likely to change as well. But I believe that, in suggesting these areas, it is better to be specific and to be wrong than to be excessively general. Specific suggestions are more likely to provoke useful (perhaps outraged) discussion. Below, I suggest four key areas for delivery system research. These are:

- Analyses of the demographics of the delivery system—i.e., of each component of the conceptual model—and relationships among the components of the model.

- Seeking ways to structure incentives so that they are likely to induce desirable change in the demography of delivery system organizations (toward the types of organizations that research indicates provide better care) and to induce these organizations to continually try to improve the value of the care they provide.

- Seeking ways to improve the measurement of provider performance.

- Analyses of interprovider/interorganizational processes for improving care.

Appendix D lists some important research (by no means a comprehensive list) done in each of the four areas and their subareas and highlights subareas where there is a particular lack of research to date. Clinical information technology is not listed as a key area for study, although this is obviously an important area that will be intensively studied. If the arguments advanced in this paper are correct, it would be helpful if much research on the implementation and effects of clinical information technology focused on the key areas suggested in this paper.

Analyses of the demographics of the delivery system and relationships among the components of the model

It is not really possible to understand what is happening in U.S. health care and why it is happening, or to formulate policies to change what is happening, without knowing the demographics of the delivery system—that is, the prevalence of various kinds of organizations and the structures these organizations take. But there is very little reliable information about the demographics of the U.S. delivery system and very little funding by Federal agencies or foundations to support obtaining this information. Knowing the demographics is an essential first step, which would make it possible to study in a generalizable way the inter-relationships outlined in the conceptual model between structure, incentives, processes, and outcomes. More specifically, research should:

- Provide definitive data on the demographics of the delivery system, for example:

- What percentage of physicians work in medical groups of various sizes and specialty types?

- What percentage of physicians, by specialty, are employed by hospitals?

- How many independent practice associations exist, and what are their characteristics?

- What percentage of physicians work in practices that function as patient-centered medical homes? What percentage are in organizations that could function as accountable care organizations?

- How many hospital-physician "integrated delivery systems" exist, and what are their characteristics?

- How can a "gold-standard," frequently updated database of the population of U.S. medical groups, including the physicians within the groups (necessary for using Medicare claims data to study group performance) be created and maintained? Lacking such a database, researchers have to invent the wheel—unsatisfactorily—every time they want to study medical groups. A few private organizations try to create such a database, but because they cannot compel physician cooperation, they are unable to do so in a way that is adequate and updated, and in any case, their databases are not publicly available. This database would be a public good. Assuming that it had the mandate and resources to do so, the Centers for Medicare Medicaid Services (CMS) would be in the best position to supply this good. Ideally, CMS could collect the information annually as a condition of physician and hospital participation in Medicare.14

- What are the demographics of other clinical staff—nurse practitioners, physician assistants, RNs, LVNs, and medical assistants—in medical groups of various sizes and specialty mixes?

- Track change over time in the demographics of the delivery system, and attempt to determine the relationship of these changes to changes in the external incentives given to provider organizations, for example:

- Is the percentage of physicians employed by hospitals changing? If so, why?

- Are physicians more likely to be employed by hospitals (and/or by large medical groups) in areas where P4P is prevalent?

- Show the structure-process-outcome relationships among components of the model for different forms of organization,15 for example:

- Which types of medical groups perform better—small, medium, or large? Single specialty or multispecialty? Hospital or MD owned?

- Which type of organization performs better: independent practice associations (IPAs) vs. large medical groups vs. integrated delivery systems vs. "accountable care organizations"?

- Do organizations that have more external incentives to improve performance use more processes (e.g., nurse care managers) to improve performance, and do they actually perform better?

We lack the most basic information about these questions. For example, it has been assumed by many reformers for decades that large multispecialty medical groups—or, better, integrated delivery systems—provide higher quality care at a lower cost. But there is very little evidence for or against this hypothesis.16,17 Recently, there has been a small amount of funding for research seeking to discover structure-process-outcome relationships for different forms of organization, but it has not been sufficient to adequately address these questions, and researchers are handicapped by lack of a gold standard census of medical groups and integrated delivery systems.

- Bring theoretical concepts, research methods, and substantive findings from fields outside health service research to the study of the delivery system18; for example, knowledge that has been gained in other fields about organizational culture, about leadership, and about change within organizations.9,19 Case studies of successful medical groups, hospitals, and integrated systems suggest that leadership and culture are very important (leaders often suggest that "culture eats strategy for lunch everyday"),20 but we know relatively little about how to measure leadership or culture in health care,21,22 and there has been very little research in health care into what types of leadership and culture exist, what their effects are on the quality/ cost of care,23,24 and what factors influence the types of leadership and culture that develop.

Analyses of ways of structuring incentives so that they are likely to induce desirable change in the demography of delivery system organizations (toward the types of organization that research indicates provide better care) and to induce these organizations to continually try to improve the value of the care they provide

There are many ways in which incentives can be structured. A research literature is developing on P4P and public reporting, but we are far from having definitive answers about the effects of these incentives.25,26 Moreover, the incentives themselves and the context in which they are offered keep changing. We have surprisingly little information about the effects of capitation or of bundled payment, and even less about the effects of these payment methods when combined with P4P and/or public reporting. There is also very little information about the effects of regulations—e.g. anti-trust enforcement against physicians, hospitals, and health plans—on the demography of delivery system organizations and on the processes these organizations use. Research should:

- Compare the effects of different payment methods—not only on the quality and costs of care, but also on the demography of the delivery system and on the extent of organizations' efforts to improve care:

- Capitation for most inpatient and outpatient services, plus public reporting and/or quality bonuses

- Real vs. virtual capitation (that is, prospectively giving the provider organization the funds anticipated to be necessary to pay for medical services vs. the pay "keeping score" and settling accounts with the provider organization at the end of the year).

- Fee-for-service payment (diagnosis related groups for hospitals) plus "shared savings"27 plus quality bonuses.

- Bundled/episode based payment:

- For services that are primarily acute and inpatient, such as cardiac or orthopedic surgery.

- For services that are chronic and outpatient, such as a year of diabetes care.

- Capitation for most inpatient and outpatient services, plus public reporting and/or quality bonuses

- Determine whether it is feasible and desirable to provide incentives at the individual physician level, or whether these incentives should be given at the level of the provider organization.28

- Compare the effectiveness of:

- P4P vs. public reporting vs. neither.

- P4P ± public reporting vs. improvement collaboratives done without financial or public reporting incentives.

Note that the observational data from research into changes in the delivery system (see above) will yield some information of interest to these questions.

- Include inquiry into unintended consequences of incentives; for example, do P4P and/or public reporting lead to:

- Increased resource disparities between hospitals and medical groups in rich and poor areas?

- "Crowding out" of important unmeasured quality by measured quality?

- Avoiding of high-risk patients by provider organizations?

- Possibly undesirable changes in the demography of provider organizations (e.g., disappearance of small practices)?

- Seek to learn more about the effects of regulations (e.g., antitrust enforcement against physicians, hospitals, and health plans) on structure, process, and outcomes in the delivery system.

- Learn what it takes to gain private health insurance plan cooperation in creating useful incentives.

Improving performance measurement

Performance measurement is critical for organizations that are trying to improve the value of the care that they provide and for the use of incentives intended to reward organizations for improving. However, reliably and validly measuring important areas of performance is not easy in health care, and experience from other industries (e.g., education) shows that inadequate performance measurement can lead to undesirable unintended consequences, particularly when measurement is linked to incentives.29 In health care, quite a lot of effort, and some Federal agency and foundation funding, has been and continues to be directed toward performance measurement, but the drive to measure is so strong that problems with measurement—reliability, validity, the possibility of unintended consequences, and the difficulty of measuring more rather than less important things—are perhaps not always given the attention they deserve.30-33 It would be very helpful to have more:

- Careful thinking and research about what measures of important areas of value (quality and cost) can effectively be used, at what levels of the delivery system (e.g., individual physician, medical group, accountable care organization), given consideration of:

- Statistical reliability.

- Ability to change the delivery system to high-performing organizations that focus continually on improving value (not just on improving scores on a limited number of process measures).

- Possible unintended consequences.

- Research into the feasibility (e.g., in terms of cost) and effectiveness of using measures of patient experience (e.g., the CAHPS®i Clinician and Group Survey) as important components of public reporting and pay for performance measures for providers.

- Research into how electronic medical records can be used to better measure quality.

Analyses of interprovider/interorganizational processes for improving care

Most research on processes to date has focused on processes that can be used to improve care within an organization—for example, within a hospital or a medical practice—with the goal of learning what processes are effective in improving quality and/or controlling costs (go to Appendix B for examples of such processes). While this goal appears self-evidently important—and is important—it may not be as important as it might seem. First, the effectiveness of a process to improve care depends very heavily on the way the process is implemented and on the context within which it is implemented.19,34 Since both implementation and context vary greatly across organizations, the results of any particular study on the effectiveness of a process may not be very generalizable.

Second, most attempts to improve care include multiple processes/components, making it difficult to learn which components are most important and amplifying the problems with lack of generalizability caused by variations in implementation and in context across organizations.

Third, even if it could be shown that a specific process is likely to be effective across a broad range of organizational contexts, few organizations will actually adopt this process unless they have a business case—that is, adequate incentives—for doing so. So it will be important to learn what types of organizations, with what types of incentives, are likely to implement processes to improve the quality of care they provide. Very few studies to date provide this kind of information.

Although intraorganizational processes are of course worthy of study, much more research should focus on critical interorganizational or interprovider processes, such as transitions of care across settings, particularly with the aim of reducing unnecessary readmissions to hospitals. Recently, there has been an increase in interest in this type of research, which I believe should continue receiving high priority. More specifically, research should focus on:

- Improving transitions in care, not just from inpatient to outpatient, or between nursing home and hospital, but also from outpatient to inpatient, as well as referrals from physician to physician. I suggest that one strong sign that a health care system is functioning well is that there is frequent phone communication between physicians about specific patients—including patients who wind up not actually being referred. Anecdotal evidence suggests that these conversations have become less frequent in recent years in the United States.

- Processes aimed at reducing readmissions.

- Resource sharing to support implementation of value-improving processes among small practices (e.g., small practices sharing a nurse care manager for patients with serious chronic illnesses).

AHRQ'S Recent ARRA Comparative Effectiveness Delivery System Initiative

AHRQ has funded an impressively large and diverse body of delivery system research. It would be a major task to try to adequately categorize the types of research funded, but overall I believe it would be accurate to say that the foci of this research and the gaps in it are consistent with the points made so far in this paper; i.e., it has focused more on evaluating processes of care, and particularly on intraorganizational processes, than on other components of the conceptual model presented in this paper or on the inter-relationships among them.

In February 2010, AHRQ used ARRA funds to issue a Request for Application (RFA) for Comparative Effectiveness Delivery System Evaluation Grants (R01), seeking proposals for "rigorous comparative evaluations of alternative system designs, change strategies, and interventions that have already been implemented in healthcare and are likely to improve quality and other outcomes." The Agency also used ARRA funds to issue an RFA for Comparative Effectiveness Delivery System Demonstration Grants (R18) seeking proposals "from organizations to conduct demonstrations of (1) broad strategies and/or specific interventions for improving care by redesigning care delivery, or (2) strategies and interventions for improving care by redesigning payment."

Through these two RFAs, AHRQ funded six evaluation grants and four demonstration grants. From the point of view of this paper, the grants selected for funding are encouraging: four of the six evaluation grants and all four of the demonstration grants arguably fall within the list of key areas suggested in this paper. The others focus on studying processes of care—such as care coordination—and devote less attention to the organizational context or to other elements of the conceptual model. The following classification of these grants in terms of the model in Figure 1 necessarily omits mention of many other, distinctive contributions of the studies' research plans, designs, and methods.

i. CAHPS is the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems family of surveys available from AHRQ at https://cahps.ahrq.gov/.