Being ready for change is a necessary, but not sufficient, prerequisite to changing your organization's approach to pressure ulcer prevention. Even when a health care organization is armed with the best evidence-based information, willing staff members, and good intentions, the implementation of new clinical and operational practices can still go awry. For example, the Implementation Team may not include members with critical knowledge of care processes or may meet too infrequently to attain any momentum. Or, changes may be planned and announced without any relation to existing procedures and practices. The work of redesign depends on the assessment of the current state of practice and knowledge, so that the plan for change is based on the needs identified specific to your organization. The timing of the change process should balance the need to act systematically and thoughtfully with the need to move quickly enough to maintain momentum by demonstrating progress.

In section 1.5, you identified members of the organization who would be willing to take ownership of the improvement effort. As mentioned, we recommend that some or all of those members be appointed to an Implementation Team to oversee the improvement effort and manage the changes required. This section is designed to help you manage change at the organizational level. To maximize the possibility of successful implementation of the pressure ulcer prevention initiative, you need to consider the following questions:

- How can we set up the Implementation Team for success?

- How do we determine whom to put on the Implementation Team?

- How can we help the Implementation Team get started on its work?

- How does the Implementation Team work with other teams involved in pressure ulcer prevention?

- What needs to change and how do we need to redesign it?

- How do we start the work of redesign?

- What is the current state of pressure ulcer prevention practice?

- What is the current state of staff knowledge about pressure ulcer prevention?

- How should goals and plans for change be developed?

- What goals should we set?

- How do we develop our plan for change?

- How do we bring staff into the process?

- How do we get staff engaged and excited about pressure ulcer prevention?

- How can we help staff learn new practices?

We return to the question of managing change at the unit level in section 4.1.5 and take up the question of sustaining change in section 6.

2.1 How can we set up the Implementation Team for success?

The success and speed of adoption of evidence-based clinical practices are related to an infrastructure dedicated to the redesign of a particular process of care. The center of this infrastructure tends to be an interdisciplinary Implementation Team that has a strong link to hospital leadership, members with the necessary expertise, a clearly defined task (e.g., develop a program to reduce pressure ulcer incidence by 75% in our hospital in the next year), and access to the resources needed to complete that task.

Trying to find one person who can do all these things, instead of a team, is both difficult and risky. Pressure ulcer prevention is a process that cuts across many different areas of hospital operations and thus requires input from all those areas. In addition, forming a team ensures that efforts will continue even if one or more members must step down or attend to other responsibilities. The Implementation Team generally assumes overall responsibility for the design and evaluation of a large-scale change in clinical practices, working with and through other teams throughout the facility. The relationships among these teams will be addressed in later sections.

Successful teams have capable leaders who help define roles and responsibilities and keep the team accountable for achieving its objectives. Senior leadership support is a prerequisite for system change, but change itself comes most effectively from the ground up. Change happens as teams that include frontline health care workers, such as physicians, actively engage in high-priority problem solving, such as redesigning processes of care.

This interdisciplinary team will have responsibility for initiating the pressure ulcer prevention project in your organization, making key decisions about the design, commissioning other teams at the unit level to carry out the improvement activities, and monitoring progress. Thus, while this team may not be involved in hands-on care, it is essential that it include some members with clinical expertise and experience who can bring that experience to bear in the team's deliberations.

You will face a number of decisions in setting up the team to lead the pressure ulcer prevention project. In section 1, we discussed the process of choosing someone to spearhead your pressure ulcer prevention project, so that person should be identified and involved in the discussion of these questions. Decisions that need to be made before convening the team include:

- How do we determine whom to put on the Implementation Team?

- How can we help the Implementation Team get started on its work?

2.1.1 How do we determine whom to put on the Implementation Team?

As suggested above, the most effective teams for initiating and overseeing a change project such as this one have several characteristics:

- An interdisciplinary team, including members from many areas with the necessary expertise to address the problem. Including wound care nurses and bedside staff as members will be key to bringing their practical knowledge and engaging them in the change process. Other members needed may not be immediately clear. We suggest using the chart below as a way to begin identifying the areas and people who need to be part of this team.

- Strong link to leadership. While some organizations have found that the only way to have adequate senior leadership support for an initiative is to include a senior leader on the team, this may not be feasible or appropriate in every case. As an alternative, consider asking senior leadership to designate a member of the top management team as the champion for the pressure ulcer prevention project. The team's leader should stay in frequent contact with the senior leader champion and can approach that person when the team encounters obstacles or needs access to senior leadership.

- Link to quality improvement expertise. The Implementation Team will be strengthened by having a member with expertise in systematic process improvement methods and in team facilitation from the quality improvement or performance improvement department. If your organization does not have a separate department with these functions, consider using informal channels to identify a person with these skills to recruit to the team. In some organizations, a member with improvement expertise successfully coleads the Implementation Team with a clinical colleague.

- Members who have influence over the areas that will need to be involved. Keep in mind that sometimes it is not possible to anticipate in advance every area that needs to be involved. It is always possible to add to the team later, but members added later will need to be oriented to the team's history and process.

You may find a chart useful in considering potential team membership. The chart can list the department, possible team members, and area of expertise.

Tools

A sample chart for identifying potential team members can be found in Tools and Resources (Tool 2A, Multidisciplinary Team).

Resources

This Web site has ideas on how to decide who should be on the Implementation Team: http://www.ihi.org/IHI/Topics/Improvement/ImprovementMethods/HowToImprove/formingtheteam.htm.

This Web site, a product of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, provides both general principles for team composition and several examples of different clinical improvement teams and their membership.

Practice Insights

Implementation Team Composition

Hospitals often found it very important that their team was truly interdisciplinary. This composition ensured that as a group, they could understand pressure ulcer prevention from multiple perspectives and integrate the hands-on knowledge and expertise into their prevention efforts.

2.1.2 How can we help the Implementation Team get started on its work?

Changing routine processes and procedures to alter the ways people conduct their everyday work is a major challenge. Successful implementation teams that achieve their goals and sustain improved performance pay attention to the development of systems of care that make the new practices for pressure ulcer prevention better than existing practices. The new practices are obvious, easier, more reliable (not reliant on memory), and more efficient than old practices.

However, the Implementation Team itself needs structure in order to achieve its objectives. The team will need to determine how often to meet. The team should also consider ground rules or guidelines for how to manage meeting time and for how to communicate, both internally and externally. The team will also need to set a timeline for its work so that there is a shared understanding of the level of urgency and priority this effort requires. Consider:

- How will the team do its work? This question refers both to the resources the team may need (information, material), and to its methods for working. How will the team keep track of issues raised, explored, and addressed? How will the team assess current knowledge and practice? How will the team use that information to redesign practice? For example, one hospital assessed staff knowledge using a structured survey and then used the survey results to design staff education activities to kick off their improvement project. In order to introduce new processes, staff members first need to learn more about the problems in current practice.

- What is the team's agenda? This related question emphasizes the importance of giving the team a clear charge and scope for its work. Can leadership provide team members with a clear understanding of the short-and long-term goals and timeframes for the implementation of improved pressure ulcer practices? For example, leadership may provide the team with a written charge that specifies target dates and improvement levels that are objectives.

Action Steps

- Establish the scope of the Implementation Team's charge.

- Develop a clear statement of the team's charge.

- Ensure that senior leadership is in agreement with this statement, and make sure that the team has access to the necessary tools and structures to allow it to succeed.

- Make sure that team members understand why they have been selected, and find ways to ensure that their efforts will be recognized.

- Ask the member from the quality improvement or performance improvement department to provide some orientation to the team on key principles and approaches used in process redesign work.

- Ensure that the team has the information it needs about the scope of the pressure ulcer problem in your facility, the reasons for the team's work, and the expected outcomes.

- Make sure the team meets regularly at the most convenient time and place and that it meets often enough to make progress.

- Develop a timetable for specific team tasks and assign members to be responsible for completion of those tasks.

Resources

This Web site has guidance on setting team goals and other aspects of team startup: http://www.ihi.org/IHI/Topics/Improvement/ImprovementMethods/HowToImprove/tipsforsettingaims.htm.

2.1.3 How does the Implementation Team work with other teams involved in pressure ulcer prevention?

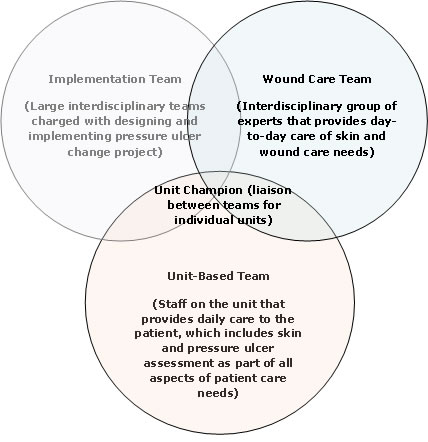

The remainder of this section discusses activities that the Implementation Team will typically be charged with, but the Implementation Team cannot carry out the entire project alone. The Implementation Team will need to collaborate with at least two other types of teams: the Wound Care Team and the Unit-Based Team in any unit where changes are to be implemented. Each team has unique responsibilities but these teams communicate and work together to make the program a success. Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between the three teams.

The Implementation Team will look at the big picture, including strengths and deficiencies in current practices and the current status of prevention and incidence tracking. This team will then determine what changes need to be made and what specific practices, tools, and resources will be needed to implement these changes. Throughout this process, the Wound Care Team may serve as an expert resource on current practices and procedures, potentially through membership on the Implementation Team. Unit Teams, also potentially represented on the Implementation Team, will actually implement the changes, integrating them into existing workflows and providing feedback about how the changes work. While the Implementation Team is likely to have a time-limited role, the Wound Care and Unit Teams will have ongoing responsibility for maintaining effective pressure ulcer practices.

Figure 1. Team relationships

No single team can make the program a success by itself. Figure 1 illustrates the overlapping and interdisciplinary nature of the team roles. In beginning its work, the Implementation Team needs to outline roles for the other teams that are clear and workable. In considering these roles during the change efforts, the Implementation Team needs to think not only about individual responsibilities but also about how the roles interact. The Implementation Team also needs to consider what ongoing communication and reporting is needed and what the best linking methods across the teams might be.

For instance, in some organizations, Unit Champions provide this coordination function. Unit Champions hold membership in both the Implementation Team and their own work units and thus serve as critical communication links. Keep in mind that there is more than one way to organize, and consider how Implementation Teams for other clinical change efforts have operated successfully within your organization in the past. Within your organization, quality improvement or performance improvement experts are likely to have expertise in how to best organize and coordinate such teams. In larger hospitals, the training and development area may also be a resource for team organization expertise.

Action Steps

- Clarify the roles that the Wound Care Team and the Unit Teams will play in the change process.

- Define the communication that is needed and the methods for linkages across teams.

2.2 What needs to change and how do we need to redesign it?

In this section, we identify the steps the Implementation Team needs to take in order to assess the current state of policy, procedures, and practice, and we indicate tools that may be useful in this process. These steps are based on the principles of quality improvement (QI), defined broadly to include system redesign and process improvement. These methods are appropriate methodologies for an effort that seeks to improve the quality of care by preventing pressure ulcers.

2.2.1 How do we start the work of redesign?

For the Implementation Team, the work of redesign has already begun through gathering the information suggested in section 1 and earlier in this section. Many of the other tools needed by the team are either provided or referenced in this toolkit. This QI process may already be familiar to your organization. If you are not sure about the strength of your organization's QI infrastructure, you may want to complete the "QI process inventory" found in Tools and Resources (Tool 2B, Quality Improvement Process ).

If some of the QI processes listed in this inventory are not fully operational or present at all in your organization, you will need to build your team's improvement capability. One strategy is to identify individuals in your organization who have improvement expertise and invite them to join the team. Another approach is to develop basic improvement skills within the team through an education process. Improvement efforts tend to be most successful when teams follow a systematic approach to analysis and implementation, and there are multiple approaches to consider. Team leaders and members may want to consult more general resources for approaches to QI projects, such as information on the Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) approach (described below in "Practice Insights"). Teams may want to spend some time initially ensuring that all necessary disciplines are represented and establishing practices for how the team will work.

If your organization already has well-established QI processes and structures, it will be beneficial to connect the pressure ulcer improvement project with those processes. For example, if you have an established reporting structure to leadership, including this project in those processes will help keep it on the leadership agenda. If managers are already evaluated on the basis of their QI efforts and results, making this project a part of the large QI enterprise in your organization will help ensure that managers are on board.

Tools

Assess your organization's current resources for QI by completing the "QI process inventory" found in the Tools and Resources section (Tool 2B, Quality Improvement Process ).

Resources

This includes a brief summary of the PDSA cycle and some clinical examples of it in use: http://www.ihi.org/IHI/Topics/Improvement/ImprovementMethods/HowToImprove/testingchanges.htm.

Practice Insights

Examples of Improvement Processes

PDSA (Plan, Do, Study, Act) is an iterative process based on the scientific method in which it is assumed that not all information or factors are available at the outset; thus, repeated cycles of change will be needed to achieve the goal, each cycle closer than the previous one. With the improved knowledge, we may choose to refine or alter the goal (ideal state).

For more information, refer to Chapter 5 in: http://www.rand.org/pubs/monograph_reports/2007/MR1267.

Six Sigma. Developed at Motorola, Six Sigma methodology is based on the careful analysis of data on process deviations from specified levels of quality and use of redesign to bring about measurable changes in those rates. Six Sigma incorporates a specific infrastructure of personnel with different levels of training in the methodology (e.g., "Champions," "Black Belts") to take different roles in the process. For more information, go to "What Is Six Sigma?" at: http://www.motorola.com/web/Business/_Moto_University/_Documents/_Static_Files/What_is_SixSigma.pdf

LEAN/Toyota Production System (TPS). TPS is an integrated set of practices designed to: bring problems to the surface in the context of continuous workflow, level out the workload, develop a culture of stopping to fix problems, promote the use of standardized tasks, enable worker empowerment to identify and fix problems, allow problems to be visible, and ensure the use of reliable technology that serves the process. For more information, go to: http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/leanprocess.htm.

2.2.2 What is the current state of pressure ulcer prevention practice?

The work of redesign begins with an assessment of the current state of practice in your organization. In addition to the tools suggested below, you may want to look ahead to section 5 for additional tools for assessing current skin status and risk rates. We suggest looking carefully at the gap between current practice and the evidence-based practices that are parts of the bundle recommended in section 3. Do any aspects of the care process already follow best practices? Are there others that diverge in small ways or in major ways? Which gaps are organizationwide, and which are specific to one or more units? If your hospital is large and complex enough that you suspect variation in current practice across units, the Implementation Team may want to start by focusing on one or two units.

Understanding the organizational context of pressure ulcer practice

As a preliminary step in documenting prevention practices on the units, the team will want to review the organizational context for the practices. Among the questions to consider:

- Have there been prior efforts to improve pressure ulcer care or prevention? Were those efforts successful? If not, what barriers did they encounter and how can you avoid the same problems? If successful, are there lessons you can build on?

- Does your organization have a certified wound care nurse? If not, what options can you create for building that expertise?

- Are physicians involved in wound care? In what ways? What are their attitudes?

- How is information about patient skin condition and risks documented and shared? What metrics, if any, are currently used to assess organizational performance with respect to skin care issues?

Understanding current processes on the units

In order to make changes to practice, it is critical to first understand what the current practices are. The fact that pressure ulcer prevention has taken on new urgency reflects one or more perceived performance problems in this area. There are gaps, possibly of multiple types, between current best practices and actual work practices due to uneven access to current information, variation in staff knowledge, and lack of coordination across different clinical units. There are also likely to be gaps between stated practices and actual practices (e.g., how often staff report they are turning patients versus how often it is actually accomplished and pressure ulcer rates and stages).

The extent and size of these gaps is usually not known until current practice is systematically examined. Understanding where any unit that is targeted for change is starting will help you identify gaps in knowledge and resources and will allow you to see how much progress is made. As reference points for these analyses, best practices for a pressure ulcer prevention bundle are outlined in section 3 and approaches to measuring pressure ulcer rates and key processes of care are outlined in section 5.

Process mapping to document current practices

One useful approach to understanding current practices is to use process mapping to examine key processes where pressure ulcer prevention activities could or should be happening. For example, process mapping can be applied to a process, such as inpatient admissions from the emergency department (ED). Mapping can specify which organizational unit or person carried out each step in the process, with particular attention to both the movement of the patient and the movement of information about the patient.

There are different approaches to process mapping, but each approach provides a systematic way to examine each step in the delivery of a specific procedure or service. Each approach can provide different insights and answer different questions. Therefore, experimentation with different data presentation options can be helpful during the redesign planning phase.

Before processes are mapped, it is necessary to identify who will conduct the mapping and to define the scope of the process to be mapped. It is also necessary to define a beginning, an end, and a methodology for all of the processes to be mapped. For example, some processes are mapped through direct observation, while others can be mapped by knowledgeable stakeholders talking through and documenting each step in the process. The mapping team should include clinical members of the Implementation Team and at least one nonclinician with some experience using this type of method. Participation in the process will not only identify opportunities for improvement, but will also engage staff so that they buy in to the proposed changes.

Observation ability and mapping improve with time, so standardization of the data collection tool and consistency in team members may be important. While it is possible to map many different processes, it is suggested that you begin by identifying key processes where, based on initial exploration, pressure ulcer prevention is likely to be of concern.

Integrating change to current work routines

Beyond the gap analysis and mapping of current practices, the team should consider how the recommended evidence-based practices can be integrated into current workflow and processes, rather than layered on top of them. One way to approach this task is to systematically assess the barriers to use of the evidence-based practices. For example, if pressure ulcer risk assessment is not being reliably completed on patients within the specific period of time from admission, what are the reasons? Is it lack of staff awareness that this should happen? Is it because it is not designated as a specific responsibility of someone during the admissions process? Is it because staff lack training in how to perform or document the results?

Action Steps

- Conduct an assessment of current practice on a sample of representative units to determine which, if any, pressure ulcer prevention practices are already in place (go to sections 3 and 5). For example, is an initial risk assessment completed within a certain timeframe of admission? If so, what tool is used? Are the results used to assign risk? What is the risk assessment process? Are prevention pathways in use for different risk categories?

- Use process mapping to describe current prevention practices and to identify problem points. Process mapping will enhance understanding of how and when pressure ulcer prevention fits into existing processes such as surgical or medical admissions, or admissions through the emergency department.

- Compare assessment results across units to determine which prevention challenges are organizationwide and which may be unit specific.

- Determine what practices need changing and consider how the new practices can be built into ongoing routines in preparation for determining how the best practices will be operationalized (discussed in section 4.1).

Tools

This worksheet in Tools and Resources has a possible approach to process mapping (Tool 2C, Current Process Analysis).

Use these worksheets to assess existing pressure ulcer prevention practices in your facility (Tool 2D, Assessing Pressure Ulcer Policies, Tool 2E, Assessing Screening for Pressure Ulcer Risk, and Tool 2F, Assessing Pressure Ulcer Care Planning).

Practice Insights

Process Mapping

One hospital found it very successful to include staff members in the process of mapping and examining key pressure ulcer prevention steps. During a staff meeting, team leaders handed out 4" x 6" pieces of paper and asked the group to work together to map all steps necessary for pressure ulcer prevention. Each person wrote one step on each piece of paper. As the team thought more about it, they were able to brainstorm more and more steps from the time a patient arrives at the hospital until the time they are released. Then, they started to use different colors to highlight potential roadblocks and risk factors along the way. In a second meeting a few weeks later, the team leader brought back the process map they had worked on. As a group, they talked about what was missing and where the potential problems are, and then each unit chose an issue to work on.

Additional Information

If you would like to learn more about process mapping, page 14 of the Toolkit for Redesign in Healthcare provides a detailed example and data collection tools: http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/toolkit/toolkit.pdf

If you would like to learn more about the current state of pressure ulcer practice, the following article provides an example of a review of practices. Catania K, Huang CH, James P, et al. PUPPI: The Pressure Ulcer Prevention Protocol Interventions. Am J Nurs 2007;107(4):44-52.

Key points from this publication include:

- Review of assets and barriers before implementation.

- Review of the literature to show the costliness of failing to prevent pressure ulcers.

- Regular monitoring and evaluation of the intervention.

2.2.3 What is the current state of staff knowledge about pressure ulcer prevention?

Due to turnover, different levels of prior knowledge and training, and other factors, it is quite likely that staff members vary in their knowledge of current pressure ulcer prevention and treatment practices. To address these gaps through education, you need to know what the gaps are and where they are located. Thus, assessing the current state of staff knowledge is critical.

Several assessment tools are available. For example, the Pieper Pressure Ulcer Knowledge Test has been used in multiple urban and rural settings to examine pressure ulcer knowledge among nurses and other professionals. Findings have shown that nurses generally have a "C" level of knowledge about pressure ulcers. Nurses with more education or years of practice have slightly higher scores, but only familiarity with national pressure ulcer guidelines or certification in wound care leads to significantly higher scores. Those who are wound certified are significantly more knowledgeable (90-94%) than those with other certifications or those without any certification. Certified Nursing Assistant scores are about 60 percent correct.

Nurses' Pieper test scores were tracked over 2 years as part of the New Jersey Hospital Association pressure ulcer collaborative. Collaborative results showed that nurses' scores significantly increased after education and that pressure ulcer incidence decreased by 70 percent. Six years of followup data showed that these results could be sustained. Physician knowledge, even among those with relevant advanced training, tends to be even more problematic.

Understanding national trends will allow you to compare the results from your facility to these averages. Regardless of what score your staff starts at, what matters is improvement over time.

Based on this analysis, the team can assess barriers to change among the staff that most likely will need to be addressed, a process that began with assessing their attitudes, as suggested in section 1. These barriers can be discerned both through the assessment of staff knowledge and through the assessment of current practice. For instance, do staff believe that a certain level of pressure ulcer incidence is inevitable? Or do they believe that risk assessment is unnecessary because preventive procedures are applied to "everyone"? Keep in mind that not all barriers may be evident at the outset, so it is important to be attentive to potential barriers as the first wave of changes are implemented.

Action Steps

- Administer an nventory of pressure ulcer knowledge to staff members. Tools are listed below for this task.

- Consider collecting demographic information so that results can be analyzed by unit and occupation. Since this is an educational needs assessment, we do not recommend asking staff to include their names, unless they want direct feedback on their score. Using names may decrease participation.

- Develop methods to correct knowledge gaps and misunderstandings.

Tools

The following two tools can be used to assess staff knowledge:

- The Pieper Pressure Ulcer Knowledge Test (Tool 2G, Pieper Pressure Ulcer Knowledge Test).

- Staff knowledge test developed by Iowa Health Des Moines (Tool 2H, Pressure Ulcer Baseline Assessment).

Additional Information

Among a group of physicians with extended training in geriatrics, 67 percent of those surveyed correctly identified a description of a Stage I pressure ulcer and only 52 percent identified a description of a Stage IV (more severe level) pressure ulcer. Less than half (48%) identified the Braden Scale for pressure ulcer risk assessment.

For more details, refer to: Odierna E, Zeleznik J. Pressure ulcer education: a pilot study of the knowledge and clinical confidence of geriatric fellows. Advs Skin Wound Care 2003;16(1):26-30.

More information on the results from the New Jersey Hospital Association pressure ulcer collaborative can be found here: Zulkowski K, Ayello E, Wexler S. Does certification and education make a difference in nurses' pressure ulcer knowledge? Adv Skin Wound Care 2007;20(1):34-38.

2.3 How should goals and plans for change be developed?

2.3.1 What goals should we set?

Once the team has completed its analysis of the gaps in pressure ulcer prevention, the team will want to review the evidence on various best practices (discussed in section 3) that may help address those gaps. However, before turning to those steps, the Implementation Team will need to set goals for improvement. These goals can be related both to outcomes (e.g., a reduction in the incidence rate of pressure ulcers related to hospitalizations) and to processes (e.g., how much of the time recommended practices for patient repositioning are followed). Goals should be related both to current internal data and to broader benchmarks and will help determine what steps the team should take next in terms of redesigning pressure ulcer prevention within your facility.

For example, your gap analysis may reveal problems in performance measures related to processes of care such as these:

- Staff are not conducting head-to-toe skin assessments within 8 hours of admission and daily.

- Risk assessment is not being documented at least daily.

In this case, you may want to set goals related to the improvement of these measures to certain levels within a certain timeframe. Alternatively, you may find that after you examine staff knowledge, certain gaps should be addressed. Other reasons for poor performance could be confusion in roles or a lack of staff communication. In these cases, goals could be set for addressing and improving these issues within a certain timeframe.

Action Steps

- Set goals for improvement based on outcomes and processes.

- Identify internal and external benchmarks against which to judge goals and progress.

- Use goals to guide next steps in redesigning pressure ulcer prevention.

Resources

For guidance on various methods to set challenging performance goals, refer to the "Setting targets for objectives" tool (p. 93) in Healthy People 2010 toolkit: a field guide to health planning. Washington, DC: Public Health Foundation; 1999. Available at: http://www.healthypeople.gov/2010/state/toolkit/ .

2.3.2 How do we develop the plan for change?

By now, the Implementation Team will be in place and you will have developed much more information about the current state of pressure ulcer knowledge, attitudes, and practices in your organization. The current state of your organization's QI practices should also be clearer, and a specific team of staff members identified to move the pressure ulcer prevention project forward. It is now time to begin developing a more specific plan for implementing new practices and for assessing that plan through the consistent collection and analysis of data. This plan will be extended and refined by work to be completed in response to additional questions (described in section 4).

While this plan will need to be flexible to respond to particular unit-based variations, it is critical that a comprehensive plan to guide next steps be formulated as you move forward. The best practices that will be discussed in the upcoming sections are critical to the implementation plan but are not independently sufficient, as they must be implemented within the context of many other factors. Also, it is important to begin thinking early about sustaining the improvements you put into place (as discussed in section 6). Thus, the implementation plan should address:

- Membership and operation of the interdisciplinary Implementation Team.

- The standards of care and practice to be met.

- How gaps in staff education and competency will be addressed.

- The plans for rolling out new standards and practices, where needed.

- Who is accountable for monitoring the implementation.

- How changes in performance will be assessed.

- How this effort will be sustained.

Tools

The "plan of action" found in Tools and Resources can be a useful template for developing your implementation plan (Tool 2I, Plan of Action ).

2.4 Checklist for managing change

2. Managing Change Checklist

| Implementation Team composition | |

|---|---|

|

___ ___ ___ |

| Team startup | |

|

___ ___ |

| Current state of pressure ulcer practice and knowledge | |

|

___ ___ ___ |

| Starting the work of redesign | |

|

___ ___ |

| Setting goals and plans for change | |

|

___ ___ ___ |