Overview: Getting Patients Off the Ventilator Faster: Slide Presentation

AHRQ Safety Program for Mechanically Ventilated Patients

Slide 1: AHRQ Safety Program for Mechanically Ventilated Patients

Overview: Getting Patients Off the Ventilator Faster

Slide 2: Learning Objectives

After this session, you will be able to–

- Describe the impact of mechanical ventilation.

- List the interventions used in the AHRQ Safety Program for Mechanically Ventilated Patients.

- List benefits of the recommended interventions.

Slide 3: How Do We Get Patients Off The Ventilator Faster?

How Do We Get Patients Off The Ventilator Faster?

Slide 4: "Never doubt..."

"Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it is the only thing that ever has."

—Margaret Mead

Slide 5: Impact of Mechanical Ventilation

- Affects 800,000 hospitalized patients in the United States each year.1

- Five to 10 percent of mechanically ventilated patients develop a ventilator-associated event (VAE).2,3

1. Carson SS, Cox CE, Homes GM, et al. The changing epidemiology of mechanical ventilation: a population-based study. J Intensive Care Med 2006; 21(3):173-82. PMID: 16672639.

2. Klompas M, Khan Y, Kleinman K, et al. Multicenter evaluation of a novel surveillance paradigm for complications of mechanical ventilation. PLoS ONE 2011 Mar 22;6(3):e18062. PMID: 21445364.

3. Klein Klouwenberg PM, van Mourik MS, Ong DS, et al. Electronic implementation of a novel surveillance paradigm for ventilator-associated events: feasibility and validation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014 Apr 15;189(8):947-55. PMID: 24498886.

Slide 6: Impact of Mechanical Ventilation

- Historically, ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) was considered one of the most lethal healthcare-associated infections.4

- 35% mortality rate for ventilated patients:5

- 24% for patients 15–19 years.

- 60% for patients 85 years and older.

4. Safdar N, Dezfullian C, Collard HR, et al. Clinical and economic consequences of ventilator–associated pneumonia: a systematic review. Crit Care Med 2005; 33(10):2184-93. PMID: 16215368.

5. Wunsch H, Linde-Zwirble WT, Angus DC, et al. The epidemiology of mechanical ventilation use in the United States. Crit Care Med 2010; 38(10):1947-53. PMID: 20639743.

Slide 7: Impact on Mechanically Ventilated Patients

Posing a significant burden to patients and caregivers.

Short-term:

- Increase in complications:

- VAP.

- Sepsis.

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

- Pulmonary embolism.

- Barotrauma.

- Pulmonary edema.

- Increase in health care costs.

- Increase in length of stay.

Long-term:

- Slower overall recovery time.

- Debilitating physical disabilities.

- Lingering cognitive dysfunction.

- Psychiatric issues, including anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Slide 8: Financial Impact of Mechanical Ventilation

- Average acute care cost for ventilated patient = $2,300 per day.6

- After fourth day, cost rises to over $3,900 per day.7

- If ventilator days were reduced by just 20 percent, patient throughput would increase leading to—

- Higher revenue.

- Ability to care for more patients.

6. Berenholtz SM, Pham JC, Thompson DA, et al. Collaborative cohort study of an intervention to reduce ventilator associated pneumonia in the ICU. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2011; 32(4):305-314. PMID: 21460481.

7. Lipitz-Snyderman A, Steinwachs D, Needham DM, et al. Impact of a statewide intensive care unit quality improvement initiative on hospital mortality and length of stay: retrospective comparative analysis. BMJ 2011;342:d219. PMID: 21282262.

Slide 9: Defining Ventilator-Associated Events

- Previous VAP surveillance definitions were subjective and nonreproducible.

- VAEs are now identified with a combination of objective criteria:

- Deterioration in respiratory status after a period of stability or improvement on the ventilator.

- Evidence of infection or inflammation.

- Laboratory evidence of respiratory infection.

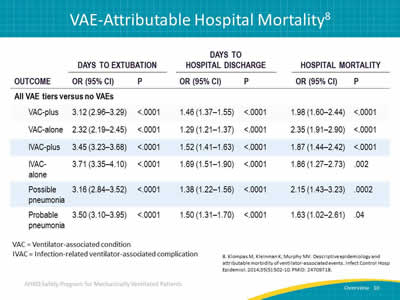

Slide 10: VAE-Attributable Hospital Mortality8

Image: A retrospective cohort study conducted between 2006 and 2011 at an academic tertiary care center calculated and compared VAE hazard ratios, antibiotic exposures, microbiology, attributable morbidity, and attributable mortality for all VAE tiers.

VAC = Ventilator-associated condition.

IVAC = Infection-related ventilator-associated complication.

8. Klompas M, Kleinman K, Murphy MV. Descriptive epidemiology and attributable morbidity of ventilator-associated events. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2014; 35(5):502-510. PMID: 24709718.

Slide 11: What Do We Need To Do?

- Improve patient and family experience.

- Reduce complications.

- Get patients off the ventilator.

- Get patients ready to leave the intensive care unit (ICU) faster.

- Improve efficiency while reducing costs.

Slide 12: AHRQ Safety Program Goals

- To reduce risk of patient harms associated with mechanical ventilation:

- Reduce ventilator-associated events, including VAP (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] definition of VAEs).

- Reduce the duration of mechanical ventilation, length of stay, and mortality.

- To achieve significant improvements in teamwork and safety culture in ICUs.

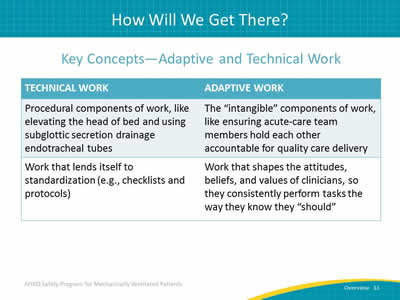

Slide 13: How Will We Get There?

Key Concepts—Adaptive and Technical Work

Image: Technical and adaptive work chart.

Slide 14: Building on Previous State-Level Success…

Michigan Keystone ICU program:

- Reduced central line-associated blood stream infections (CLABSI).9,10

- Reduced VAP.6

- Reduced mortality rate.7

- Improved safety climate in ICUs.11

- Reduced health care cost.12

- Improved patient outcomes.

6. Berenholtz SM, Pham JC, Thompson DA, et al. Collaborative cohort study of an intervention to reduce ventilator associated pneumonia in the ICU. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2011; 32(4):305-314. PMID: 21460481.

7. Lipitz-Snyderman A, Steinwachs D, Needham DM, et al. Impact of a statewide intensive care unit quality improvement initiative on hospital mortality and length of stay: retrospective comparative analysis. BMJ 2011;342:d219. PMID: 21282262.

9. Pronovost P, Needham D, Berenholtz S, et al. An intervention to decrease catheter- related bloodstream infection in the ICU. N Engl J Med 2006;355(26):2725-32. PMID: 17192537.

10. Pronovost PJ, Goeschel CA, Colantuoni E, et al. Sustaining reductions in catheter related bloodstream infections in Michigan ICUs: observational study. BMJ 2010;340:c309. PMID: 20133365.

11. Sexton JB, Berenholtz SM, Goeschel CA, et al. Assessing and improving safety climate in a large cohort of intensive care units. Crit Care Medicine 2011;39(5):934-9. PMID: 21297460.

12. Waters HR, Korn R Jr, Colantuoni E, et al. The business case for quality: economic analysis of the Michigan Keystone Patient Safety Program in ICUs. Am J Med Qual 2011;26(5):333–339. PMID: 21856956.

Slide 15: …and National-Level Highlights

National On the CUSP—Stop BSI program:13

- Initiative to implement Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program (CUSP), a proven culture change model, along with bundled interventions to prevent CLABSI.

- A total of 1,071 intensive care units in 45 States.

- A 43 percent reduction in CLABSI rates.

- The number of intensive care units that achieved CLABSI rate of zero more than doubled.

13. Eliminating CLABSI, A National Patient Safety Imperative: Final Report. Content last reviewed January 2013. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/cusp/clabsi-final/index.html. Accessed September 21, 2016.PMID: 24018921.

Slide 16: Ventilator-Associated Events Successes

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Epicenters’ Wake Up and Breathe Collaborative14

- What: Prospective quality improvement collaborative.

- Who: 12 ICUs affiliated with 7 hospitals.

- Why: Prevent VAEs through less sedation and earlier liberation from mechanical ventilation.

- How: Increase performance of paired daily spontaneous awakening trials (SATs) and spontaneous breathing trials (SBTs).

14. Klompas M, Anderson D, Trick W, et al. The Preventability of Ventilator-Associated Events: The CDC Prevention Epicenters' Wake Up and Breathe Collaborative. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015 Feb 1;191(3):292-301. PMID: 25369558.

Slide 17: Ventilator-Associated Events Successes

CDC Epicenters’ Wake Up and Breathe Collaborative14

SATs and SBTs Increases:

- +63% in SATs.

- +16% in SBTs.

- +81% in SBTs done with sedatives off.

Ventilator Days and Length of Stay (LOS) Reductions:

- -2.4 vent days.

- -3.0 ICU days.

- -6.3 LOS days.

VAE Reductions:

- -37% in VACs.

- -65% in IVACs.

Images: Arrow pointing up covering SATs and SBTs Increases. Arrow pointing down covering reductions in ventilator days, length of stay, and VAE.

14. Klompas M, Anderson D, Trick W, et al. The Preventability of Ventilator-Associated Events: The CDC Prevention Epicenters' Wake Up and Breathe Collaborative. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015 Feb 1;191(3):292-301. PMID: 25369558.

Slide 18: Interventions

Interventions

Slide 19: Interventions

- CUSP.

- Daily Care Processes.

- Early Mobility.

- Low Tidal Volume Ventilation.

Image: Infographic showing technical and adaptive interventions.

Slide 20: Intervention 1—CUSP13

Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program

- Educate staff on the Science of Safety.

- Identify defects:

- How can we get patients off the ventilator faster?

- Partner with a senior executive.

- Learn from defects.

- Improve teamwork and communication.

13. Eliminating CLABSI, A National Patient Safety Imperative: Final Report. Content last reviewed January 2013. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/cusp/clabsi-final/index.html. Accessed September 21, 2016.PMID: 24018921.

Slide 21: Intervention 2—Daily Care Process Measures

- Use subglottic secretion drainage endotracheal tubes in patients expected to be ventilated for >72 hours.

- Elevate head of bed to a semi-recumbent position (≥30°).

- Minimize sedation level.

- Use SAT with validated sedation scale daily.

- Assess readiness to wean daily with SBT.

- Assess then address delirium.

Slide 22: Intervention 3—Daily Early Mobility

- Use multidisciplinary and coordinated approach.

- Employ a nurse-driven protocol.

- Minimize sedative use and interrupt sedation daily.

- Screen for eligibility for mobilization.

- Tailor goals to maximize mobility.

Slide 23: Intervention 4—Low Tidal Volume Ventilation15

- Prevent ARDS.

- Use positive end-expiratory pressure ≥5 cm H2O, not zero end-expiratory pressure.

- Maintain plateau pressure at ≤30 cm H2O.

- Use tidal volume of 6–8 cc/kg predicted body weight in patients who do not have ARDS, 4-6 cc/kg predicted body weight in patients who do have ARDS.

15. Lellouche F, Lipes J. Prophylactic protective ventilation: lower tidal volumes for all critically ill patients? Intensive Care Med 2013;39(1), 6-15. PMID: 23108608.

Slide 24: 2014 SHEA Compendium Update16

Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America

- Elevate the head of the bed 30–45 degrees.

- Provide endotracheal tubes with subglottic secretion drainage ports for patients likely to require more than 48 or 72 hours of intubation.

- Manage ventilated patients without sedation whenever possible.

16. Klompas M, Branson R, Eichenwald EC, et al. Strategies to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia in acute care hospitals: 2014 update. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2014;35(8):915-936. PMID: 25026607.

Slide 25: 2014 SHEA Compendium Update16

- Interrupt sedation once a day (SAT).

- Assess readiness to extubate once a day (SBT).

- Pair SATs with SBTs.

- Employ early exercise and mobilization.

- Use noninvasive positive pressure ventilation whenever feasible.

16. Klompas M, Branson R, Eichenwald EC, et al. Strategies to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia in acute care hospitals: 2014 update. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2014;35(8):915-936. PMID: 25026607.

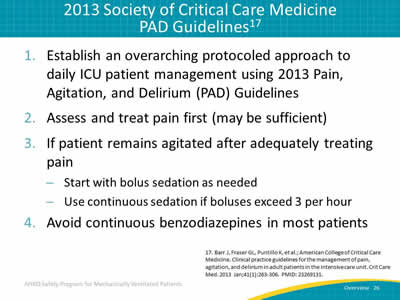

Slide 26: 2013 Society of Critical Care Medicine PAD Guidelines17

- Establish an overarching protocoled approach to daily ICU patient management using 2013 Pain, Agitation, and Delirium (PAD) Guidelines.

- Assess and treat pain first (may be sufficient).

- If patient remains agitated after adequately treating pain:

- Start with bolus sedation as needed.

- Use continuous sedation if boluses exceed 3 per hour.

- Avoid continuous benzodiazepines in most patients.

17. Barr J, Fraser GL, Puntillo K, et al.; American College of Critical Care Medicine. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2013 Jan;41(1):263-306. PMID: 23269131.

Slide 27: 2013 Society of Critical Care Medicine PAD Guidelines17

- Interrupt sedation daily:

- If necessary to restart, use lowest dose possible to maintain target level of consciousness.

- Avoid deep sedation; instead, target awake or alert.

- Screen for delirium with validated tool:

- If delirious, first seek reversible causes and attempt nonpharmacological management.

- Use ABCDE bundle to improve outcomes for your patients.

17. Barr J, Fraser GL, Puntillo K, et al.; American College of Critical Care Medicine. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2013 Jan;41(1):263-306. PMID: 23269131.

Slide 28: ABCDEF Bundle18

- Awakening and,

- Breathing coordination.

- Choose light sedation.

- Delirium monitoring/management and,

- Early exercise/mobility bundle.

- Family and patient involvement (new).

18. Balas MC, Burke WJ, Gannon D, et al. Implementing the awakening and breathing coordination, delirium monitoring/management, and early exercise/mobility bundle into everyday care: opportunities, challenges, and lessons learned for implementing the ICU Pain, Agitation, and Delirium Guidelines. Crit Care Med 2013;41(9):S116-27. PMID: 23989089.

Slide 29: Questions?

Image: Series of hanging colored tags with question marks on them.

Slide 30: References

1. Carson SS, Cox CE, Homes GM, et al. The changing epidemiology of mechanical ventilation: a population-based study. J Intensive Care Med 2006; 21(3):173-82. PMID: 16672639.

2. Klompas M, Khan Y, Kleinman K, et al. Multicenter evaluation of a novel surveillance paradigm for complications of mechanical ventilation. PLoS ONE 2011 Mar 22;6(3):e18062. PMID: 21445364.

3. Klein Klouwenberg PM, van Mourik MS, Ong DS, et al. Electronic implementation of a novel surveillance paradigm for ventilator-associated events: feasibility and validation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014 Apr 15;189(8):947-55. PMID: 24498886.

4. Safdar N, Dezfullian C, Collard HR, et al. Clinical and economic consequences of ventilator–associated pneumonia: a systematic review. Crit Care Med 2005; 33(10):2184-93. PMID: 16215368.

Slide 31: References

5. Wunsch H, Linde-Zwirble WT, Angus DC, et al. The epidemiology of mechanical ventilation use in the United States. Crit Care Med 2010; 38(10):1947-53. PMID: 20639743.

6. Berenholtz SM, Pham JC, Thompson DA, et al. Collaborative cohort study of an intervention to reduce ventilator associated pneumonia in the ICU. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2011; 32(4):305-314. PMID: 21460481.

7. Lipitz-Snyderman A, Steinwachs D, Needham DM, et al. Impact of a statewide intensive care unit quality improvement initiative on hospital mortality and length of stay: retrospective comparative analysis. BMJ 2011;342:d219. PMID: 21282262.

8. Klompas M, Kleinman K, Murphy MV. Descriptive epidemiology and attributable morbidity of ventilator-associated events. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2014; 35(5):502-510. PMID: 24709718.

Slide 32: References

9. Pronovost P, Needham D, Berenholtz S, et al. An intervention to decrease catheter- related bloodstream infection in the ICU. N Engl J Med 2006;355(26):2725-32. PMID: 17192537.

10. Pronovost PJ, Goeschel CA, Colantuoni E, et al. Sustaining reductions in catheter related bloodstream infections in Michigan ICUs: observational study. BMJ 2010;340:c309. PMID: 20133365.

11. Sexton JB, Berenholtz SM, Goeschel CA, et al. Assessing and improving safety climate in a large cohort of intensive care units. Crit Care Medicine 2011;39(5):934-9. PMID: 21297460.

12. Waters HR, Korn R Jr, Colantuoni E, et al. The business case for quality: economic analysis of the Michigan Keystone Patient Safety Program in ICUs. Am J Med Qual 2011;26(5):333–339. PMID: 21856956.

Slide 33: References

13. Eliminating CLABSI, A National Patient Safety Imperative: Final Report. Content last reviewed January 2013. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/cusp/clabsi-final/index.html. Accessed September 21, 2016.PMID: 24018921.

14. Klompas M, Anderson D, Trick W, et al. The Preventability of Ventilator-Associated Events: The CDC Prevention Epicenters' Wake Up and Breathe Collaborative. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015 Feb 1;191(3):292-301. PMID: 25369558.

15. Lellouche F, Lipes J. Prophylactic protective ventilation: lower tidal volumes for all critically ill patients? Intensive Care Med 2013;39(1), 6-15. PMID: 23108608.

16. Klompas M, Branson R, Eichenwald EC, et al. Strategies to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia in acute care hospitals: 2014 update. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2014;35(8):915-936. PMID: 25026607.

Slide 34: References

17. Barr J, Fraser GL, Puntillo K, et al.; American College of Critical Care Medicine. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2013 Jan;41(1):263-306. PMID: 23269131.

18. Balas MC, Burke WJ, Gannon D, et al. Implementing the awakening and breathing coordination, delirium monitoring/management, and early exercise/mobility bundle into everyday care: opportunities, challenges, and lessons learned for implementing the ICU Pain, Agitation, and Delirium Guidelines. Crit Care Med 2013;41(9):S116-27. PMID: 23989089.