Environmental Scan Report

The York framework21 for conducting scoping reviews was used to direct the environmental scan.22–25 Scoping reviews contextualize knowledge of the field by systematically mapping the literature on a topic; identifying key concepts, theories, and sources of evidence; and identifying gaps in current research. A scoping review analyzes a wide range of research and nonresearch material to provide greater conceptual clarity about the field.

The York framework for scoping reviews is composed of six phases to guide evidence synthesis. These include:21

- Identifying the research question and setting a purpose for the study.

- Identifying relevant research and nonresearch materials.

- Selecting studies.

- Abstracting data.

- Collating, summarizing, and reporting the results.

- Consulting with consumers and stakeholders to suggest additional references and provide insights beyond those in the literature.

Using this approach, our project team produced the following deliverables:

- Synthesis of research in the field,

- Inventory and description of current interventions being used to increase patient and family engagement in primary care settings to improve patient safety,

- Qualitative evaluation of effectiveness and usability of interventions identified, and

- Identification of gaps in the field and areas ready for intervention development.

Phase 1. Identifying Research Question and Purpose

The primary research question that the environmental scan addresses is:

What are effective and potentially generalizable approaches for engaging patients and families to improve patient safety in primary care settings?

Phase 2. Identifying Relevant Research and Nonresearch Materials

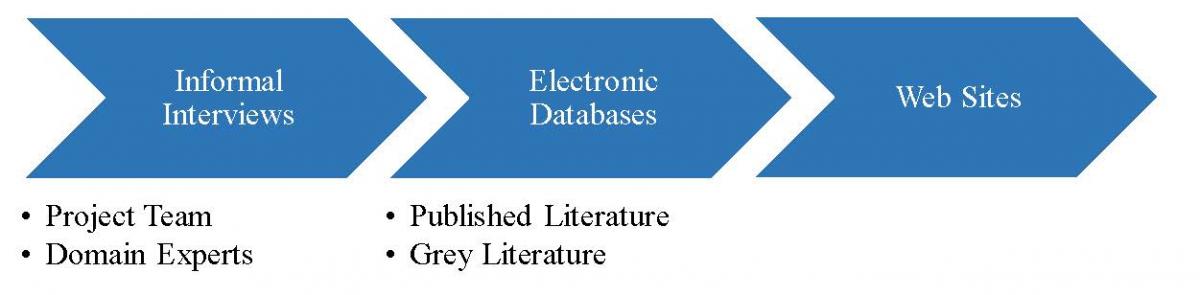

To have a comprehensive search, the York framework recommends searching several literature sources, including electronic databases, reference lists of relevant literature, key journals (hand search), and existing networks, relevant organizations, and conferences.21–23 Informal interviews and surveys of subject matter experts help to inform the search strategies and identify Web sites for grey literature searching. Figure 2 provides a high-level overview of our approach to identifying relevant research and nonresearch materials during phase 2.

Figure 2. Process of Identifying Research and Nonresearch Materials

Step 1. Informal Interviews and Surveys

We conducted informal interviews and surveys first with our project team and then with identified domain experts, including patients and family members. The interviews were designed to help us refine our definitions, search terms, and strategy, and identify interventions and resources pertinent to Guide development.

The informal interview questions are provided in Appendix A and include the following topics:

- Conceptualization of patient safety and patient engagement in primary care

- Identification of search terms and input on approach

- Advice on organizations, Web sites, and potential interventions

- Key constructs to assess usability, sustainability, and generalizability of interventions

- Recommended research (peer-reviewed and grey literature) to be reviewed

- Recommendations for other individuals to be included in interviews

The subjects of the informal interviews included:

- Project team members.

- MedStar Health’s (MSH) network of patient and family advisory committees on quality and safety (PFACQS). This network includes nationally recognized patient and family advocates, community representatives from each of the 10 MSH hospitals and 3 PFACQS serving MSH's more than 238 practices.

- Domain experts, who are individuals with high-level expertise in areas pertinent to the project, such as patient engagement, patient activation, patient safety, health literacy, and primary care practice.

Due to the nature of the informal outreach as part of the environmental scan, a fast-track Office of Management and Budget (OMB) clearance and institutional review board approval were obtained before we conducted interviews and surveys.

Step 2. Electronic Literature Database Search

The project team devised a broad list of terms pertinent to patient safety, patient and family engagement, and primary care (Appendix B). These terms were combined to create keywords to search both peer-reviewed and grey literature electronic databases. We also reviewed Tanon and colleagues’ (2010) paper on the appropriate search terms for identifying papers on patient safety in MEDLINE®, Embase, and CINAHL.26 In addition, we consulted with librarians to search Patient Safety Net (PSNet, psnet.ahrq.gov) to identify appropriate medical subject heading (MeSH) terms.

Appendix C outlines a sample search strategy for the peer-reviewed literature search. This strategy was modified and expanded to include search terms relevant to identifying "tools" or "interventions" conducted in "primary care" settings. Keywords were mapped to database thesauri search terms, where available, and also as text word terms in the databases as per protocol.21 Our goal was to conduct a sensitive search of the literature focused on identifying interventions at the intersection of patient safety, patient and family engagement, and primary care.

All literature database searches were limited to the English language and non-English articles with English abstracts, published between 2011 and November 2015. This date range was selected to build on the comprehensive outcomes reported in the environmental scan produced by AHRQ's Guide to Patient and Family Engagement in Hospital Quality and Safety.27

To be comprehensive, we also reviewed reference lists of relevant articles, Web sites, and grey literature, along with specific journal issues to identify related published and nonpublished resources. These were validated through further consultation from domain experts and the project Technical Expert Panel (TEP).

We enlisted two clinical library scientists specializing in patient safety to support the electronic searching of the peer-reviewed literature. We gave the librarians five core readings from the field to validate the sensitivity of the search strategy. Once validated, the search strategies and approaches were modified to meet the variability of search string formats for the different peer-reviewed electronic databases. We ran the searches and removed duplicate articles to establish a core list of candidate articles to move forward for initial review and subsequent abstraction.

Table 1 summarizes the electronic databases used to search the peer-reviewed and grey literature.

| Type of Literature | Databases |

|---|---|

| Peer-Reviewed Literature |

|

| Grey Literature |

|

At least two trained searchers with differing backgrounds and expertise in the field of patient safety reviewed the de-duplicated list of candidate articles and nonresearch evidence for relevance. After initial review, the search strategy was further refined to focus on identification of "interventions" that have demonstrated effectiveness at improving patient safety and/or patient and family engagement. This provided a more focused listing for further review by abstraction teams. A final listing of peer-reviewed and nonresearch-related articles and reports was generated for review of inclusion and exclusion and abstraction.

Step 3. Web Site Search

After we selected relevant material from the electronic literature database search, we conducted a targeted review of select Web sites and social media sites to increase the capture of emerging approaches to improving patient safety in primary care. Through consultation with our stakeholders and members of the project team, we compiled a list of relevant organizations and Web sites to search (Appendix D).

We searched the Web sites in a systematic manner, allowing some variation in search strategies in response to varied Web site structures. Our approach included consulting the Web site's site map to identify research, publication, or tool links to facilitate searching. Once we completed this hand search, we used the Web site's search engine to uncover additional materials. For all Web sites, we searched the terms "patient and family engagement," "patient safety," "primary care," "patient engagement," and "medical error." We kept a log of the Web site searches, saving the links to relevant pages and tracking our progress through the Web sites, along with copies of all materials and resources obtained during these searches.

We also surveyed non-peer-reviewed resources in a process that paralleled the approach to the peer-reviewed literature in order to stretch beyond the established evidence base. The goal here was to identify individual clinics and other independent exemplars that may have promising locally developed tools and innovations to increase patient and family engagement in patient safety. We hypothesized that not all interventions that have been demonstrated to be successful at improving patient and family engagement would be represented in the peer-reviewed literature but may be disseminated by exploiting social media outlets.

Several conduits for this information include:

- Social media, such as Twitter activity associated with distinct hash tags (e.g., #PFAC2015, #patientvoice, #patientengagement) or organizational/individual handles (e.g., @theNPSF or @CRICOstrategies);

- Meeting abstracts;

- Twitter feeds;

- Blog archives (e.g., KevinMD, Paul Levy "not running a hospital," The HealthCare Blog, ePatient Dave, and Wachter’s World);

- Presentations from major patient safety and primary care conferences (e.g., National Patient Safety Foundation and American Academy of Pediatrics annual meetings);

- Newspaper databases;

- TED Talk archives; and

- Google news feeds.

Building on the use of published and widely available materials from the organizations listed above, the cognitive interviews and informal surveys of subject matter experts yielded the identification of membership organizations, existing tools, and specific primary care practices to include in the Guide.

Phase 3. Selecting Studies

The broad search terms resulted in a high yield of abstracts, interventions, and reports returned for preliminary review. To remove irrelevant material, we developed a screening protocol with specific inclusion and exclusion criteria based on the focus areas identified within our research question. Table 2 outlines our inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Table 2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

|

|

Operationally, we used the following guidance to decide which reports to include:

- Although the focus of this environmental scan was on resources related to interventions, other empirical studies that addressed critical issues in the intersection of patient safety, primary care, and patient and family engagement were also included. These included, for example, surveys of patients and providers about the issues and consensus processes to develop practice guidelines.

- Reports that explicitly addressed only two of the three conceptual domains (patient safety, PFE, primary care) were included only if they could plausibly be interpreted to include the third.

- Reports that focused on health promotion (e.g., smoking cessation, diet) and disease prevention (e.g., encouraging vaccination or cancer screening) were not regarded as addressing patient safety and were not included.

- Reports that focused on general safety issues (e.g., bicycle helmets, personal security) unrelated to medical treatment were not regarded as addressing patient safety and were not included.

- Reports that focused on falls in the home were not regarded as addressing patient safety unless the falls were explicitly related to medication errors or similar problems.

- Reports about outpatient care of patients with specific advanced diseases were not regarded as dealing with primary care unless the report explicitly mentioned that the intervention was used in a primary care setting.

- Reports about the management of patients with multiple chronic diseases in primary care settings were included only if reducing patient safety problems (e.g., medication management) was explicitly mentioned as a goal or outcome of the intervention.

- Reports about interactions (e.g., handoffs, medicine reconciliation systems) among caregivers (e.g., physicians and nurses, hospital and primary care staff, pharmacists, and primary care staff) without explicit mention of patients were generally not regarded as including patient and family engagement.

- Reports without explicit mention of patient and family engagement were included only if there was a potential for patient engagement (e.g., home visits or medication management).

Members of the project team piloted the inclusion/exclusion criteria with a subsample of abstracts retrieved from the MEDLINE database. Two groups of three reviewers were assigned 10 articles each to test the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The two groups met and developed a consensus approach to article/intervention inclusion (Table 2).

Once we developed the final set of inclusion/exclusion criteria, we trained a team of abstractors and worked with the abstractors until the interrater reliability was κ ≥0.6. Abstractors then applied the accepted inclusion/exclusion criteria. In addition to peer-reviewed articles, we applied the inclusion/exclusion criteria to reports, theses, and policy analyses.

We used a similar screening process for literature and resources uncovered through Web site searching, reference lists, and key informant recommendations. We also included materials from Web sites representing less formal, interpretive descriptions of studies, programs, investigations, or interventions that were on Web pages and may or may not have been linked to report documents. A final list of resources, peer-reviewed and non-peer-reviewed sources, and resources meeting the inclusion criteria proceeded to Phase 4 for data abstraction.

Phase 4. Abstracting Data

According to the York methodology, the data abstraction process is multistaged, involving abstraction of information from individual articles or resources. Our abstraction process evolved throughout the project. The key criteria for preliminary abstraction included:

- Resource title.

- Brief description of resource, approach, intervention.

- Triad elements addressed (patient safety, patient and family engagement, primary care).

- Patient safety problem(s) addressed.

- Intervention identified (Yes/No).

- Include for further review (Yes/No).

- Publicly available resource.

We trained a team of six to conduct preliminary abstraction and categorization. At least two abstractors reviewed each resource. A senior researcher adjudicated differences between the reviewers relative to inclusion. We anticipated that there would be few if any randomized controlled trials (RCTs) addressing the effectiveness of interventions at the intersections of patient safety, patient and family engagement, and primary care. Thus, we adopted a "best evidence" approach, focusing on studies that met applicable methodological standards for qualitative studies, implementation science, case studies, and expert consensus panel reports.14,28–33

Phase 5. Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results

The purpose of this stage was to provide a structure to the literature and resources uncovered by the search. Due to the broad scope of our research question and the large volume of literature and resources uncovered in our searches, we constrained this final stage to a narrative synthesis. We organized the findings into specific categories, including patient safety, patient and family engagement, primary care, and the intersections therein.

The content team conducted thematic analysis of the evidence and assigned themes to the peer-reviewed literature, grey literature, and key informant survey results. Themes were organized around the following domains:

- Quality of evidence

- Conceptual domains (patient safety, patient and family engagement, primary care)

- Safety issues addressed

- Safety solutions

These domains were informed by a combination of our project team’s experience in the field and informal interviews and surveys with stakeholders, including:

- Patients and families;

- Primary care practice staff and providers; and

- Researchers in patient safety, communication, pharmacy, patient engagement, shared decisionmaking, quality and outcomes research, implementation science, and health care delivery systems science.

The abstractors independently coded each article for the quality of evidence, conceptual domain addressed, safety issue addressed, and safety solutions, using the categories outlined in Table 3. Our senior researchers reviewed and reconciled the categorizations. A report was assigned only one category for quality of evidence. It was then assigned at least two conceptual domains and could have multiple safety issues and safety solutions. We revised the categories to include safety issues and safety solutions that emerged as we reviewed the literature. The safety issues and solutions are defined and illustrated with examples in Appendix E.

Table 3. Reporting Categories and Codes

| Category | Codes |

|---|---|

| Quality of Evidence |

|

| Conceptual Domains |

|

| Safety Issues |

|

| Safety Solutions |

|

Abstractors independently coded each resource for categories along the four domains. Once resources were categorized, a team of patient safety domain experts reviewed and identified interventions for further consideration for inclusion in Guide development.

Phase 6. Consulting With Consumers and Stakeholders

Stakeholder consultation was ongoing throughout the environmental scan process, informing each phase of the scan activities through informal and formal interactions with stakeholders.21 Stakeholders identified for the project included:

- Patients, family members, and lay caregivers.

- Primary care providers.

- Primary care practice staff.

- Practice administrators.

- Researchers.

- Pharmacists and other affiliated health care providers.

- Safety and quality improvement professionals.

Early involvement of stakeholders allowed us to seek guidance regarding the research question, search terms and strategy, and organizations and Web sites for review. We could also ensure that the results represented the interests of key stakeholder groups—patients, families, caregivers, primary care providers, and primary care practice staff—who were the intended audience for the deliverables to be developed and disseminated as part of the Guide activities.

We sought stakeholder input to inform both the environmental scan and to identify exemplar practices and interventions for consideration as case studies. To identify interventions that improve patient safety through patient and family engagement or within the primary care practice environment, we selected individuals with the knowledge, expertise, and experience in these areas to participate in our environmental scan activities. Our interviews with these key informants focused on identifying interventions from the peer-reviewed literature and non-peer-reviewed sources. The semistructured interview guides for patients, providers, and practice staff are available in Appendix A.

Individuals were invited to participate via email, in person, or telephone consultation with the project team members. Domains of interest for key informant input were:

- Feedback on research question and study purpose.

- Threats to patient safety in primary care.

- Identification of interventions to engage patients and families in primary care settings.

- Existing interventions, tools, and resources for patient engagement to improve patient safety in primary care.

- Barriers and facilitators of adoption of these interventions.

- Organizations or Web sites that should be reviewed.

- Approaches to dissemination of the Guide materials.

Data collection was conducted and reported in the REDCap™ database and summarized and synthesized using standardized approaches for content analysis and thematic review.34,35 Common themes emerging were validated by the key informants and additional subject matter experts as well as by members of the project's Technical Expert Panel (TEP). TEP members also served as key informants in the identification process.