Environmental Scan Report

Key Informant Interviews

We consulted 12 project team members early in the environmental scan to inform the initial search strategies, domains of interest, and conceptualization of the project goals and research question. From this input, we developed questions for key informants and stakeholders (Appendix A). Upon receiving OMB approval in December 2015, we conducted a survey of patients and patient advocates, primary care providers, and practice staff and seected researchers in patient safety and behavior change on the domains of interest. We also solicited input from TEP members.

A total of 23 individuals responded to our request for technical input. Table 4 lists stakeholder groups represented. We asked individuals to indicate all groups they were representing with their responses.

Table 4. Stakeholder Groups Providing Technical Input

| Stakeholder Groups | Number (N=23) |

|---|---|

| Patients | 13 |

| Family members | 14 |

| Caregivers | 7 |

| Nurses | 3 |

| Physicians | 10 |

| Pharmacist | 1 |

| Other providers* | 2 |

| Primary care practice staff | 4 |

| Researchers | 4 |

| Health care administrators | 3 |

| Patient safety or quality improvement officers | 4 |

| Policymakers | 1 |

*Quality Improvement Network; patient safety advocate.

We recorded and categorized responses. We specifically sought common themes around conceptualization of patient safety and patient engagement in primary care to build on the evidence from AHRQ's Guide to Patient and Family Engagement in Hospital Quality and Safety8 and further inform the conceptual model for patient safety and patient and family engagement in primary care. The key themes that emerged along each of these conceptual domains are summarized below.

Conceptualization of Patient Engagement in Primary Care

One overarching common theme emerged around the concept of patient engagement in primary care—partnership.

From the perspective of our key informants, patients and providers reported similar characteristics of what patient engagement in primary care means and what it should look like. One provider defined patient engagements as "a practice or behavior that allows and encourages the patient and their families to contribute in their medical care decisionmaking in an informed way that may exceed or even fall short of interventions and education that is offered by the caregiver." This provider specified that engagement occurs when the patient and provider discuss the different options and then come to an agreement on what is achievable given the individual patient’s needs, values, and preferences, as well as the patient's confidence in his or her ability to achieve the plan and the goals.

Another primary care provider indicated that patient engagement means that patients are "on top of their medications, treatments, and that they are actively keeping records of their care along with me as their primary care doctor." One provider stated this explicitly in that "we have to move away from the no news is good new mentality to one of no news equals no news. When a patient calls saying that they haven’t heard about a test, my call back starts with a thank you for being a partner in your care." An important patient-identified barrier to engagement, simply stated, is that "engagement is useless without communication and being able to communicate concerns about their care and care experience to the doctor."

Conceptualization of Patient Safety in Primary Care

When asked about the concept of patient safety in primary care, our informants' responses focused on the primary care practice as the environment or setting for patient safety to be strengthened. Few identified the health care system (e.g., issues associated with fragmentation of care or continuity of care between acute and primary care settings) and community (e.g., issues associated with community pharmacy or other community-level health care professionals) as determinants of safety. Many identified the need to better understand patient-related factors (e.g., cost of medications) that affect a patient’s ability to adhere to recommended treatments and therapies.

Most informants viewed factors related to the complex relationships among the key stakeholders within the practice setting—physician, patient, and practice staff—as the key to patient safety in primary care. Here, communication breakdowns, slips, and lapses were the most commonly reported determinants of patient safety in primary care. This referred not only to communication between the patient and the physician during the clinical encounter, but also to communication between primary and specialty care providers. It also included accurate specimen labeling, medication reconciliation with the patient, and staff requests for two patient identifiers (e.g., check name and date of birth when confirming test results or sending medication orders to the pharmacy). Other related safety behaviors identified by key informants included openness, trust, transparency, and relationship-based care.

Threats to Patient Safety in Primary Care Settings

Four common themes emerged from our key informants as threats to patient safety in primary care settings: breakdowns in communication, medication-related errors, factors influencing incorrect or incomplete diagnosis, and factors related to fragmentation of the health care system. Table 5 provides a summary of each domain and the informant-identified safety issues within that domain.

Table 5. Key Informant-Identified Threats to Patient Safety in Primary Care

| Theme | Threats to Patient Safety |

|---|---|

| Communication |

|

| Fragmentation |

|

| Medication issues |

|

| Issues related to diagnosis and treatment |

|

Recommended Interventions To Improve Patient Safety and Patient Engagement in Primary Care

Our key informants identified interventions at the patient, provider, and practice environment level to improve patient safety.

Patients. Each of the 23 key informants reported that a major factor to improve patient safety in primary care was the need for patients to take a more active role in their care. Strategies identified by the informants to improve engagement and patient safety included:

- Ask questions. All informants identified preparing patients to ask questions at the office visit as an important first step. Providing opportunities to support question asking, including providers encouraging questions, should be considered as part of the Guide.

- Take an active role in treatment decisions. Having patients take an active role in treatment decisions is vital to improving patient safety. Active engagement in decisionmaking includes providing the physician with all the information needed to make a sound clinical judgment, listening to advice on lifestyle and behavioral factors that may influence poor health, and becoming "information seekers" rather than just "passive recipients" of care. Efforts within the Guide need to support a patient and provider team to encourage patient accountability in care. They also need to ensure that the patient's voice is being heard.

- Be prepared to be a patient. Several individuals identified that ensuring that patients are aware of the expectations of being a patient is important. This includes knowing why they are at the doctor, being prepared for the appointment with questions, being open about problems and challenges in the care plan, and bringing a family member or friend with them to the appointment, particularly if expecting bad news.

- Speak up. The concept of partnership is tightly coupled with a patient’s role in the patient-provider relationship, shifting from a patient listening to a paternalistic doctor to being an active partner. One intervention prepares patients with the tools to speak up when something a provider says is unclear or when information is missing or incomplete. The intervention also helps providers make it easy for patients to speak up both when things are good and when they are not.

- Improve medication understanding and use. Our informants indicated that a comprehensive approach to patient medications is an important factor influencing patient safety and care quality in primary care. Patients need to know what they are taking, understand why they are taking it, and understand the implications of nonadherence.

- Own your medical information. Themes around patient ownership of their medical record were reported by patients, physicians, practice staff, and administrators. Making sure that patients had access to their medical records, most often recommended through a patient portal or other electronic means, was encouraged.

- Communicate openly. Patients and patient advocates often responded that the ability to have open electronic communication with primary care providers would yield higher levels of engagement and improve patient safety. Electronic communication types identified included email, communication through a patient portal, and the opportunity to text message the provider. Timely access to providers through the telephone was also encouraged.

Providers. Common provider-directed interventions and approaches aimed at improving patient safety and patient engagement in care included:

- Motivational interviewing. Informants emphasized the need for strategies to enhance the providers' skills and competencies at coaching, setting goals, and working with patients to agree on health priorities and set realistic expectations. The provider can be a coach or instructor to empower patients and family members to be engaged in their care and become partners. Informant recommendations included undergraduate and graduate medical education reform to include skills building around these topics as important first steps in the process.

- Teach-back. Patients and providers felt that an important approach to ensuring understanding of information and encouraging open communication is through the effective and consistent use of "teach-back." With teach-back, when a patient receives new information, the patient "teaches" that new information back to the provider. Informants recommended using teach-back whenever a new medication is prescribed, an old medication is renewed, or a new therapy is discussed. Teach-back can also be used to ensure understanding about why a test is being ordered to reinforce to the patient how important it is to get the test or adhere to the new medication.

- Shared decisionmaking. Patients and providers identified strongly with efforts to improve shared decisionmaking. Specific strategies or interventions to enable shared decisionmaking were not as common as the identified need for shared decisionmaking.

- Contextualized care. Many informants reported that interventions aimed at encouraging identification of patient-level barriers to implementing the care plan are critical to improving safety. These barriers include life preferences, health numeracy, context of care, socioeconomic pressures, and health literacy.

- Appropriate language. Changing the language used by providers in primary care from "medical jargon to living room language" was identified by several informants as a key feature to improve patient safety. This approach could help create a sense of equity in decisionmaking and allow patients to better engage in their care.

Practice Setting. Several approaches identified by our informants aimed to improve patient safety and patient engagement but required changes in operations, infrastructure, or organization in order to be adopted. We defined these approaches as interventions to be applied at the practice setting level, even though they may require individual patient, provider, or practice staff behavior change to be most effectively adopted.

- Patient portals. Patients, providers, and other health care stakeholders agree that a well-functioning, accessible, and usable patient portal is a critical feature that can cross the patient safety-patient engagement chasm in primary care. Information available through the portal should include "all the patient’s health information and NOT just selected parts." A patient portal has been identified as an important method of enhancing communication, a vehicle to identify potential errors in information, and a historical record of the plan of care. Informants suggested that a patient portal with access to test results would also allow patients and their family members or caregivers to know when test results arrive at the doctor’s office and, more importantly, if they have not.

- Patient and family advisory councils, boards, or committee models. Our key informants overwhelmingly supported the idea of engaging patients and families in a structured way to improve the quality, safety, and effectiveness of care in the primary care setting. One physician indicated that it would be "ideal for primary care practices to have a patient advisory group—not all can manage that process—but where they can, they should. Much insight is gained through listening to patients and having them in a leadership role."

- Team huddles. All key informants identified efforts to improve communication between physicians, patients, and practice staff as a critical factor to improve patient safety and patient engagement in primary care. Team huddles and other principles of high-reliability organizations were recommended to reduce the opportunity for errors in communication, enhance clinical teamwork and effectiveness, and establish practice resilience and ability to respond to unexpected emergencies.

- Models of team-based care. Approximately 35 percent of our informants identified team-based care as a critical factor that can improve both patient engagement and patient safety in primary care. Benefits of care teams in this context include allowing increased time with patients, fostering meaningful patient-provider relationships, and improving patient and provider satisfaction. Recommended models included nurse/physician extenders, concierge practice model, team screening and taking of medical and social history, team documentation, and coaching and education done by an extended team. In these models, the patients engage with the full team and not just the physician.

- Support for shared decisionmaking. Patients and providers identified shared decisionmaking as important to improving patient safety and engagement in care. Approaches suggested to support shared decisionmaking included decision aids, option grids, patient and provider checklists, and other risk tools.

- Previsit labs. Obtaining lab tests before the visit encourages shared decisionmaking and limits the need for followup. Previsit labs reduce the risk associated with patients forgetting to have the tests done and the risk of the practice team or provider forgetting to follow up on test results.

- Usable materials. Informants indicated that providing patients with usable tools they can pick up and take home would help support open communication and decisionmaking. These include decision aids, patient educational materials, and access to their medical record. Providers cautioned, however, that in their experience "…decision aids are great for the already activated and educated patient. Providers need to be sensitive to the less educated or health literacy challenged populations and develop strategies to encourage activation among all patient groups."

Literature Review

Peer-Reviewed Literature

The initial search strategies for the peer-reviewed literature yielded more than 11,000 indexed references in the PubMed database. To reach a more manageable and relevant selection of articles, the project team consulted with the medical library scientists to refine the search and filter the results to focus on identifying articles with interventions (and related concepts such as toolkits, processes, and process improvements). This more focused approach yielded 1,163 articles to undergo further review. The library scientists then conducted the additional searches using the Embase, CINAHL, Cochrane, and Web of Science databases.

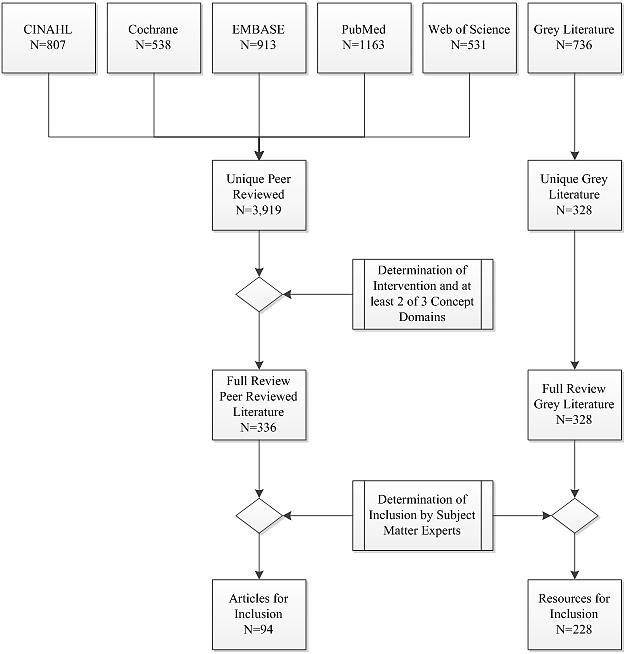

As illustrated in Figure 3, the search of the electronic literature databases yielded the following numbers of reports:

- PubMed, 1,163,

- Embase, 913,

- CINAHL, 807,

- Cochrane, 538, and

- Web of Science, 531.

These were examined for duplicates, and 3,919 unique articles were identified. Six members of the research team, paired in teams of two (three teams of two reviewers), independently reviewed article abstracts to make initial determinations of whether the article addressed patient safety, patient and family engagement, or primary care. Of these, 336 reports met the predetermined inclusion criteria of reporting on an intervention that addressed at least two of the three conceptual domains.

One of the senior researchers subsequently reviewed the 336 reports and identified 94 that met the predetermined inclusion criteria (see Table 2 for criteria). The 94 peer-reviewed articles were merged with the grey literature and key informant interview output to develop the inventory of interventions and inform the findings below.

Grey Literature

The process for identification of resources within the grey literature followed a similar approach to that used with the peer-reviewed literature (Figure 3) and yielded 536 source documents that met the inclusion criteria of reporting on two or more of the conceptual domains of patient safety, patient and family engagement, and primary care. An additional 200 resources were identified through searches of Google, Twitter, and other social media outlets or through the social networks of the project team and the AHRQ contracting officer. These resources were reviewed independently by two senior patient safety researchers for consideration.

After review, deduplication, and consideration of relevance of the reports and resources to the goals of the Guide, 328 unique resources were identified for full review. One of the senior researchers subsequently reviewed these 328 resources and identified 228 that met the predetermined inclusion criteria (see Table 2 for criteria).

Figure 3. Peer-Reviewed and Grey Literature Flowchart

Overall Analysis

Each unique article or resource was independently coded for the quality of evidence, conceptual domain addressed, safety issue addressed, and safety solutions, using the categories first provided in Table 3. The number of reports in each of the categories for both the peer-reviewed and grey literature are presented in the tables below (Table 6, Table 7, Table 8, Table 9).

Table 6. Number of Reports by Report Type, Safety Issues, and Safety Solutions Addressed

| Peer-Reviewed Literature | Grey Literature | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Report Type | N (94) | % | N (328) | % |

| Evaluated intervention | 33 | 35.1 | 68 | 20.7 |

| Well-described intervention | 28 | 29.8 | 292 | 89.0 |

| Systematic review | 18 | 19.1 | 11 | 3.4 |

| Other | 15 | 16.0 | 31 | 9.5 |

Table 7. Number of Reports by Conceptual Domain

| Peer-Reviewed Literature | Grey Literature | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conceptual Domains Addressed | N (94) | % | N (328) | % |

| Patient safety | 85 | 90.4 | 310 | 94.5 |

| Primary care setting | 92 | 97.9 | 292 | 89.0 |

| Patient and family engagement | 65 | 69.1 | 291 | 88.7 |

Table 8. Number of Reports by Safety Issue Addressed

| Peer-Reviewed Literature | Grey Literature | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Safety Issues Addressed | N (94) | % | N (328) | % |

| Fragmentation of the care system and transitions between providers | 24 | 25.5 | 250 | 75.3 |

| Communication between patients and providers, health literacy | 34 | 36.2 | 280 | 85.4 |

| Diagnostic errors | 2 | 2.1 | 129 | 39.3 |

| Medication prescription, management, drug interactions, adherence | 54 | 57.4 | 119 | 36.3 |

| Antibiotic, opioid, and other medication overuse | 10 | 10.6 | 7 | 2.1 |

| Other | 16 | 17.0 | 62 | 18.9 |

| Not addressed | 10 | 10.6 | 0 | 0 |

Table 9. Number of Reports by Safety Solution

| Safety Solutions | Peer-Reviewed Literature | Grey Literature | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (94) | % | N (328) | % | |

| Care team models, including pharmacists | 40 | 42.6 | 187 | 57.0 |

| Medications, medication lists, reconciliation | 38 | 40.4 | 133 | 40.5 |

| Family advisory councils | 0 | 0.0 | 79 | 24.1 |

| Educational interventions | 44 | 46.8 | 243 | 74.1 |

| Shared decisionmaking models | 10 | 10.6 | 89 | 27.1 |

| Family engagement in patient care | 5 | 5.3 | 97 | 29.6 |

| Chronic disease management | 19 | 20.2 | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 14 | 14.9 | 0 | 0 |

| Not addressed | 17 | 18.1 | 0 | 0 |

Peer-Reviewed Literature

Slightly more than one-third of the published articles that met the inclusion criteria reported on an evaluated intervention (33 articles, or 35.1%; Table 6). The level of rigor of the evaluations varied, and some evaluations revealed negative effects of the intervention on outcomes assessed.

Another 18 articles (19.1%) included systematic reviews of the literature. Many of these reviews included only a small number of medium- or high-quality articles and relatively few strong conclusions about effective interventions. Another 28 articles (29.8%) provided good descriptions of interventions but focused on protocols, case studies, or toolkits and did not report the results of evaluations.

The remaining 15 articles (16.1%) did not include descriptions of interventions. They reported on surveys of patients and providers about the issues, consensus processes to develop practice guidelines, and other empirical studies that addressed critical issues in the intersection of patient safety, primary care, and patient and family engagement.

Most studies reviewed explicitly addressed patient safety (85 articles, or 90.4%; Table 7) in primary care settings (92 articles, 97.9%). However, only 65 articles (69.1%) directly addressed patient and family engagement.

The most common safety issues addressed were medication prescription and management, drug interactions, and adherence (54 articles, or 57.4%; Table 8). An additional 10 articles covered the related area of antibiotic, opioid, and other medication overuse, for a total of 64 articles (68.0%) on medication issues. Other frequent patient safety issues addressed were communication between patients and providers, including health literacy (34 articles, 36.2%) and fragmentation of the care system and transitions between providers (24 articles, 25.5%). Two articles (2.1%) addressed diagnostic errors. The remaining reports either addressed a different patient safety issue (16 articles, 17.0%) or did not explicitly address patient safety at all (10 articles, 10.6%).

The most common patient safety solutions identified in the peer-reviewed literature were educational interventions (44 articles, or 46.8%; Table 9); care team models including pharmacists (40 articles, 42.6%); and health information technology (IT), including medications, medication lists, and reconciliation (38 articles, 40.4%). There were also articles on chronic disease management models (19 articles, 20.2%), shared decisionmaking models (10 articles, 10.6%), and family (beyond patient) engagement in patient care (5 articles, 5.3%).

No articles discussing family advisory councils in the context of primary care were identified by this search. The remaining reports either addressed a different patient safety solution (14 articles, 14.9%) or did not explicitly address patient safety solutions at all (17 articles, 18.1%).

Grey Literature

The grey literature search yielded 328 tools, interventions, reports, and other resources aimed at improving patient safety and patient and family engagement in primary care settings that met our initial inclusion criteria. Of the reports identified, about 20% met the threshold for being well evaluated, including 11 systematic reviews (Table 6). These reports also included consensus panel reports that may or may not have identified interventions for consideration. Most of the reports were defined as well-described interventions, approaches, processes, or reviews with consensus panel recommendations for improving patient safety and patient engagement in primary care settings.

Most of the resources identified by our grey literature search addressed our conceptual domains of patient safety (94.5%), primary care (89%), and patient and family engagement (88.7%; Table 7). Of these, 273 (83.2%) addressed all three domains.

The most common safety issues addressed in the grey literature included communication breakdowns (85.4%; Table 8), fragmentation issues (75.3%), diagnostic errors (39.3%), and issues around medications (38.4%). This profile is somewhat similar to the peer-reviewed literature search where communication, medication, and fragmentation issues were the top three patient safety concerns identified.

In the grey literature, solutions to overcoming patient safety concerns in primary care were often multifactorial in nature, with few interventions focused on only one problem (Table 9). Care team models, including approaches to frame the patient and family members as part of the care team, were the most commonly reported interventions in the grey literature to target patient safety and patient engagement in primary care. Other commonly reported interventions included medication reconciliation and medication lists, models and decision aids to support shared decisionmaking, and strategies to engage patients and family members as advisors, board members, or active participants in their care.

One feature common across most of the interventions, tools, and reports was education. Education was included as a key strategy to foster the adoption of interventions and enabling technologies. Activities aimed at educating patients were replete throughout the grey literature. Educational activities for providers and practice staff were also represented but to a much lesser extent. Our search also identified reports aimed at engaging the academic and policy communities in the dialogue around patient safety and patient engagement in primary care.

Interventions

Subject matter experts, including patient representatives, a health literacy expert, a systems delivery scientist, patient safety experts, a human factors specialist, and safety scientists, independently reviewed the 422 reports considered for inclusion in the Guide. Of the 328 resources identified in the grey literature search, 251 described interventions in sufficient detail to warrant review and usability considerations. Of these, experts determined that 228 should be considered for inclusion in the Guide. Similarly, 72 interventions identified within the peer-reviewed literature were included in the intervention inventory. Appendix F contains a table of the interventions identified for consideration for inclusion in the Guide.