Low Tidal Volume Ventilation: Introduction, Evidence, and Implementation: Facilitator Guide

AHRQ Safety Program for Mechanically Ventilated Patients

Slide 1: Low Tidal Volume Ventilation: Introduction, Evidence, and Implementation

Say:

This module introduces and provides evidence for the lung protective low tidal volume strategy, and offers recommendations for implementation.

Slide 2: Learning Objectives

Say:

After this session, you will be able to define low tidal volume ventilation, referred to as LTVV. You will also be able to describe the role of LTVV in the prevention of ventilator-associated events, outline the historical background and scientific evidence supporting the use of LTVV, and recommend evidence-based standards for implementing a LTVV strategy.

Slide 3: What is Low Tidal Volume Ventilation?

Say:

You may be somewhat familiar with the concept of low tidal volume strategy. Your unit may already be implementing a low tidal volume ventilation strategy to protect your patients’ lungs, or you may need more information to drive the process forward and engage your staff. First, let’s define LTVV.

Ask:

What is low tidal volume ventilation strategy?

Say:

LTVV is a lung protective strategy that seeks to prevent ventilator-associated lung injury. It targets much lower tidal volumes than those that have been traditionally used while also focusing on the avoidance of zero positive end-expiratory pressure (ZEEP).

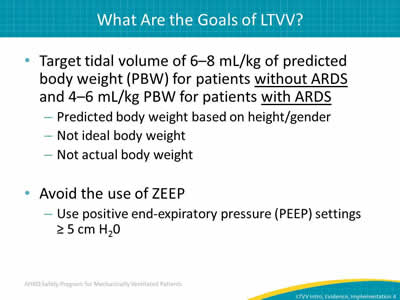

Slide 4: What are the goals of LTVV?

Say:

LTVV is an approach that targets tidal volume between 6 and 8 milliliters per kilogram of predicted body weight for patients without acute respiratory distress syndrome or ARDS, and 4 to 6 milliliters per kilogram of predicted body weight for those with ARDS. Predicted body weight is the key measurement, and is based purely on the patient’s height and their gender. It’s not based on their actual body weight, nor even an ideal body weight.

The other big component of low tidal volume strategy is the avoidance of the use of ZEEP. We’ll explain some of the data advocating for positive end-expiratory pressure settings, or PEEP, at or above 5 centimeters of water. Predicted body weight and PEEP are the two main components of low tidal volume ventilation.

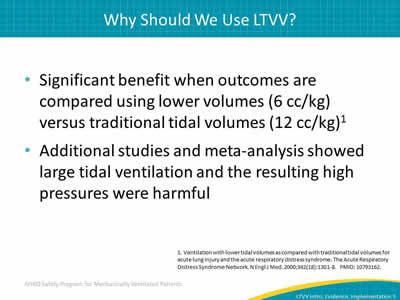

Slide 5: Why Should We Use LTVV?

Ask:

So why should we be using a LTVV strategy?

Why should we be taking this approach in trying to apply it to our patients?

Say:

The 2000 ARDSNet study found a significant benefit for patients with ARDS when using lower tidal volumes (6 cc/kg versus a more traditional tidal volume of 12 cc/kg. More recent studies confirm that LTVV benefits ARDS patients. However, low tidal volume strategies are probably beneficial in all mechanically ventilated patients, beyond only ARDS patients.

A low tidal volume strategy has become the standard of care for patients with ARDS as well as the best practice in order to improve outcomes in those patients. In addition, the emerging evidence indicates that LTVV is a best practice for all ventilated patients to reduce ventilator-associated harm.

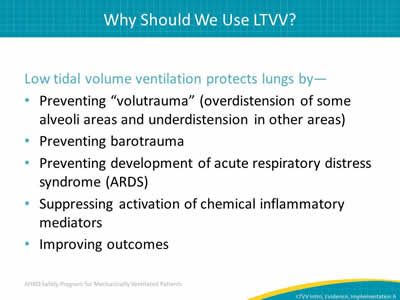

Slide 6: Why Should We Use LTVV?

Ask:

Why should we use low tidal volume?

What is the major benefit?

Say:

Low tidal volume ventilation, or LTVV, protects lungs from a variety of insults and injuries associated with mechanical ventilation. Complications include volutrauma (in which overdistention of some alveoli areas and underdistention of other areas occurs), and barotrauma, which causes complications from high pressure that can lead to catastrophic tension pneumothoraces, and also localized injury to the alveoli. Mechanical ventilation can activate a variety of inflammatory mediators in the lungs, thus accelerating injury and increasing incidence of ARDS. LTVV can help ameliorate these complications and improve outcomes.

Slide 7: History Review

Ask:

So, how did we get here?

Say:

Let’s take a step back and review the history of mechanical ventilation.

Slide 8: Early History

Say:

Mechanical ventilation as we know it today actually goes back to 1776, when Dr. John Hunter, an enterprising researcher, developed a double bellows system. His system pushed air in and out of the lung. His work was performed on dogs rather than humans, and used a set of tubes inserted into the canine trachea (one tube took air in and another tube carried air out). Dr. Hunter circulated air in and out of the lungs.

Several physiologists conducted research over the next 50 years to develop mechanical ventilation. By 1837, chest compressions were preferred for moving air in out of the lungs. Not cardiopulmonary resuscitation or CPR, with fast chest compressions over the heart, but instead a chest compression technique designed to help push the air out and pull the air back in. It was a popular method in the early 1800s. Other researchers were developing positive as well as negative pressure ventilation systems.

By 1850, the French Academy of Sciences published that what we now call barotrauma, such as tension pneumothoraces, rupture of alveoli, and emphysematous changes in the lungs, was reported in patients receiving mechanical bellows system ventilation. This damage caused clinicians to abandon positive pressure ventilation for years. This paper was particularly influential in changing direction in how we could provide artificial respiration. Over the next 100 years, research in this field focused on developing negative pressure ventilation.

Slide 9: The Iron Lung

Say:

And, of course, the ultimate negative pressure ventilation technique was what we refer to as the iron lung. Use of the iron lung was common during the polio epidemics of the 1950s. You may have seen this famous picture. This photograph is not of polio victims, but was staged with volunteers. This and similar images were associated with the polio epidemic and amplified a collective fear of paralysis and artificial ventilation. Negative pressure ventilation was at a peak during this time.

Slide 10: Positive Pressure Vents Still Progressed

Say:

Despite the clinical focus on negative pressure systems, others continued developing positive pressure ventilator systems. In fact, Johann Dräger pushed forward in this area. One device developed in 1907, the Pulmotor, was more commonly used by rescue teams and fire departments for resuscitation efforts in the field. But the development of these devices informed the modern ventilators. Today, Dräger is a leading international company in the fields of medical and safety technology, producing ventilators and anesthesia machines.

Slide 11: Endotracheal Intubation

Say:

Another medical practice that helped propel positive pressure ventilator development was endotracheal intubation. The polio epidemic outstripped the supply of iron lungs, returning attention to the use of positive pressure ventilation. Until the late 1950s and the early 1960s, it was extremely uncommon to insert a breathing tube outside of the operating room. But as endotracheal intubation became more acceptable in acute care settings, use of positive pressure ventilation increased.

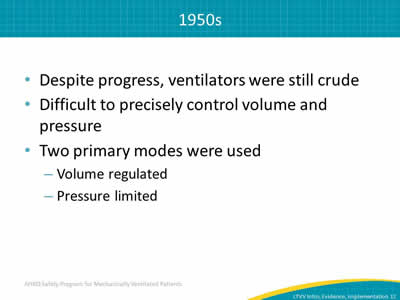

Slide 12: 1950s

Say:

The early ventilators provided a fairly crude system. Precise control was difficult with only two primary modes: volume regulated or pressure limited.

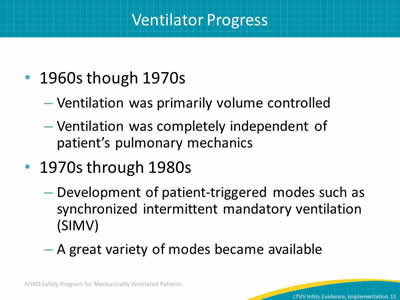

Slide 13: Ventilator Progress

Say:

During the 1960s and 1970s, ventilation was primarily volume controlled and completely independent of the patient’s pulmonary mechanics. However, by the 1980s, synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation mode became widely available, and then ventilation modes expanded.

Slide 14: Supporting Research

Say:

So let’s discuss traditional ventilation strategies. We’ve talked about what constitutes low tidal volume. In comparison to what we’ve been doing for the last 40 or 50 years, we have to ask some questions.

Ask:

Where does the traditional practice come from?

Why have we been using 10 ccs or greater per kilo of body weight for the last 50 years?

Say:

It used to be that every patient on mechanical ventilation received at least 10 cc/kg tidal volume. If you weighed 70 kilos, then you received a 700 cc tidal volume.

Ask:

Why were clinicians doing that?

Why were many of us taught to do that?

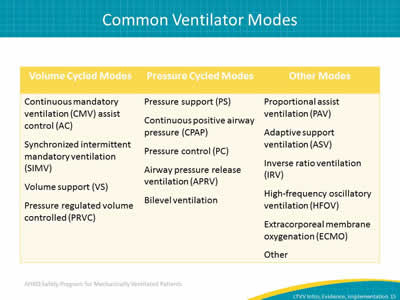

Slide 15: Common Ventilator Modes

Say:

For hospitals interested in implementing a low tidal volume ventilation strategy as part of their ventilator-associated events reduction efforts, a LTVV data collection tool is available. The ventilator modes have three categories: volume cycle modes, pressure cycle modes, and other modes.

The volume cycle modes are modes where you set the volume. Next, the pressure cycle modes target a specific pressure limit, which might generate a range of volumes from breath to breath. Last, other modes include extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, high frequency oscillatory ventilation, and proportional assist ventilation. In these modes, you cannot set or even ascertain a typical tidal volume in the patient. Patients receiving mechanical ventilation set to one of the other modes may not be receiving a low tidal volume strategy.

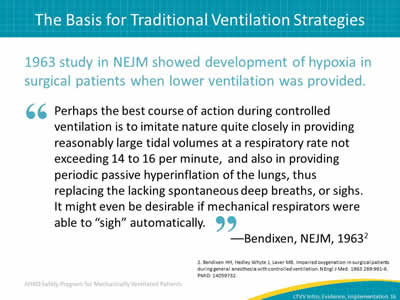

Slide 16: The Basis for Traditional Ventilation Strategies

Say:

It stems from a 1963 study in the New England Journal of Medicine by Bendixon. This study in surgical patients found that patients who received low tidal volumes intraoperatively were hypoxic. At the time, they didn’t fully understand the cause. The researchers assumed the hypoxia was caused by shunts due to atelectasis, the complete or partial collapse of a lung or lobe of a lung. They assumed that low tidal volumes caused lungs to collapse, leading to shunt and hypoxia.

Bendixon suggested that patients should have generous tidal volumes and reasonably low respiratory rates to ensure that the lungs inflated fully, so that the atelectasis was prevented. This paper dictated the standard of practice in intensive care units, ICUs, for many years.

Slide 17: Traditional Ventilation Strategies

Say:

This information has been disseminated in virtually every medical textbook. In fact, if you look in anesthesiology textbooks published earlier than recent years, between 10 and 15 cc/kg is the recommendation for tidal volume.

The other factor that drove this phenomenon was oxygen toxicity. In the 1960s, particularly in newborns, data showed that high oxygen levels were potentially toxic. Understandably, there was a real reluctance to use high FIO2 levels to overcome the kind of shunts that Bendixon found. Since it was believed that Bendixon’s study found that the higher tidal volume prevented hypoxia, clinicians were able to avoid using toxic levels of oxygen.

Slide 18: The Problem With Large Tidal Volumes (Vt)

Say:

But this approach has its own individual harms. In acute lung injury (ALI), there’s a breakdown in the lung architecture and there is capillary leak. Many patients receive mechanical ventilation because they have some sort of pulmonary failure or ALI. This leads to stiff lungs, and can lead to overinflation and underinflation in air distribution across the lungs.

This can result in over distention of some lung areas, what we refer to as volutrauma, which is considered a major cause of ventilator-associated injuries. It also leads to inflammatory changes, additional tissue injury, and more stiffness. It reduces compliance, which pushes the patient’s initial lung cycles in a never-ending process that further assaults the lungs into adult acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Slide 19: The Problem With Large Tidal Volumes (Vt)

Say:

Larger tidal volumes could also lead to barotrauma, or damage due to pressure, which can cause rupture of the alveoli and tension pneumothoraxes. There’s also a cyclical type of trauma that occurs, often called “atelectrauma.” Shear stresses are generated in the alveoli as they pop open and snap close. This drives the inflammatory process. The large tidal volume strategy, the standard of care for the last 40 or 50 years, has consequences that are harmful to patients. It could take patients who have only mild lung injury, and actually accelerate and even exacerbate the process and deteriorate their lung condition into ARDS. As a result, researchers have proposed using lower tidal volumes and allowing mild to moderate respiratory acidosis to improve outcomes.

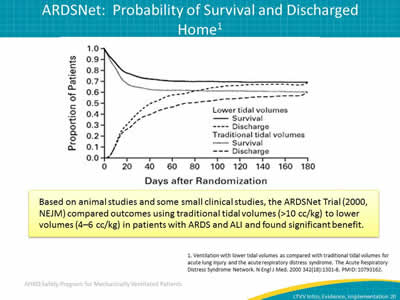

Slide 20: ARDSNet: Probability of Survival and Discharged Home

Say:

Many animal trials and small clinical trials challenged the standard practice of large tidal volume. Comparisons to low tidal volume strategies suggested benefits to dropping the tidal volume in patients on mechanical ventilators. In 2000, the New England Journal of Medicine published the ARDSNet Trial. The researchers randomized patients who met the criteria for ARDS to either the traditional tidal volume strategy (initial tidal volume of 12 cc/kg of their predicted body weight or a lower tidal volume strategy (initial tidal volume of 6 cc/kg of their predicted body weight). They found substantial improvement in the survival rate of patients receiving the lower tidal volumes.

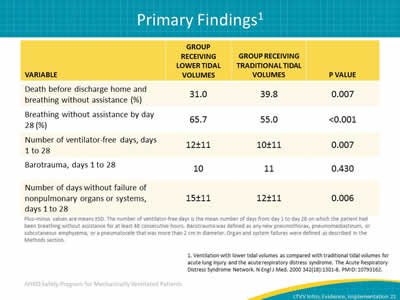

Slide 21: Primary Findings

Say:

The primary findings of the ARDSNet study were significant reduction in death before discharge home and an increase in number of days of breathing without assistance in those who received the lower tidal volume strategy. A substantial improvement was also found in the number of patients who were able to breathe without assistance by day 28. To clarify, that included people who were off the ventilator and didn’t need a bilevel positive airway pressure or continuous positive airway pressure.

The incidence of barotrauma did not differ between the two groups. A statistically significant improvement was observed in the number of days without failure of nonpulmonary organs or systems.

A lower tidal volume strategy in ARDS patients improved their lung function and helped them get off the ventilator faster, but it also improved other organ failure system scores. This suggests that the inflammatory injury in the lungs from the traditional tidal volume strategy was not only affecting the lungs, but affecting the other organ systems as well. That makes sense because we know inflammatory mediators and inflammatory cytokines don’t remain in the lung. They can circulate throughout the rest of the body. By harming the lungs, larger tidal volumes were actually harming the rest of the patient. By helping to protect the lungs, we improve all other organ systems.

In many ways this landmark study completely changed the way we manage patients receiving mechanical ventilation. Keep in mind that the ARDSNet trial focused on patients with ARDS.

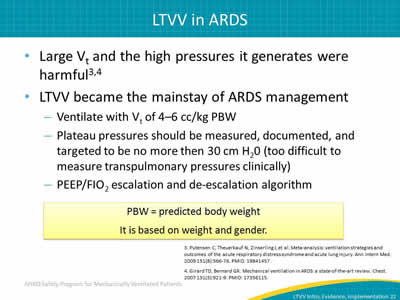

Slide 22: LTVV in ARDS

Say:

LTVV became the mainstay of therapy for ARDS patients and included three key elements: ventilate with 4 to 6 cc/kg of the patient’s predicted body weight based on height and gender; measure plateau pressures and adjust the ventilator to try to maintain the plateau pressures below 30 centimeters of water; and to use a PEEP and FIO2 escalation and deescalation algorithm to assist with oxygenation.

PEEP, as we mentioned earlier, is a core component of low tidal volume strategy.

Ask:

Why is that the case?

Say:

PEEP counteracts a lot of the downsides that low tidal volume strategy creates. In 1963, Bendixon and his colleagues were correct about one thing. Low tidal volumes can lead to atelectasis and, of course, that can lead to shunt. But the Bendixon study didn’t use PEEP. They used zero end-expiratory pressure, or ZEEP. When patients exhaled, their lung pressure fell to atmospheric pressure levels. That factor allowed areas of their lungs to collapse and led to atelectasis.

In the years that led to the ADRSNet study, evidence showed that maintaining an adequate PEEP could counteract the effect that Bendixon saw on these low tidal volume strategies. PEEP recruits the alveoli; it helps prevent them from collapsing at end-expiration, and it essentially eliminates the problems associated with atelectasis and shunt when running a low tidal volume strategy. To reiterate, for ARDS patients, the three components of LTVV, an appropriate VT based on the patient’s predicted body weight, PEEP, and FiO2, became the mainstay of therapy and have been the standard of care for the last 15 years.

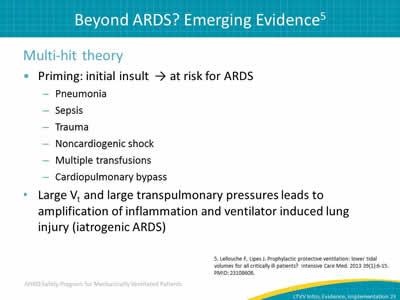

Slide 23: Beyond ARDS? Emerging Evidence

Say:

Our focus then extends beyond ARDS patients

Ask:

What is the emerging evidence?

Does this kind of tidal volume strategy paradigm shift apply not only to ARDS patients, but potentially to virtually every patient who receives mechanical ventilation, even for short periods of time?

Say:

Well, we know that progressing to ALI and ARDS is probably due to multiple factors. There’s some sort of priming insult, such as pneumonia, sepsis, severe trauma, noncardiogenic shock, multiple transfusions due to large blood losses, or having to undergo cardiopulmonary bypass. And, once the complications assault the patient, the system is primed for further injury.

Once mechanical ventilation is necessary due to the priming insults, traditional tidal volume practices can then accelerate the process through the volutrauma, barotrauma, and inflammatory mediators that are byproducts of large tidal volumes. We have essentially taken a patient who is at risk for ARDS due to a priming insult, and then fueled the fire, so to speak, with a traditional ventilator strategy. The traditional strategy can push patients to ARDS who otherwise might never have progressed toward ARDS.

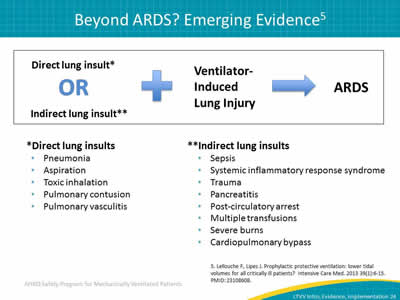

Slide 24: Beyond ARDS? Emerging Evidence

Say:

First, the patient experiences a primary insult, which can be a direct or indirect pulmonary insult, and then can experience a secondary insult associated with mechanical ventilation strategies that have been used for the last 40 or 50 years, and that in fact, cause unintended consequences and progress the patient’s processes to what could be viewed as iatrogenic ARDS.

Direct pulmonary insult includes pneumonia, aspiration, toxic inhalation, pulmonary contusion, or pulmonary vasculitis. Indirect pulmonary insult includes extrapulmonary sepsis, systemic inflammatory response syndrome from trauma, pancreatitis, and post-circulatory arrest as well as multiple transfusions, severe burns, and cardiopulmonary bypass. Insults secondary to mechanical ventilation include ventilation-induced lung injuries.

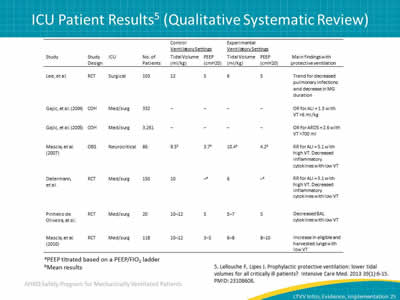

Slide 25: ICU Patient Results (Qualitative Systematic Review)

Say:

Since the 2000 ARDSNet study, there have been a number of studies on how lower tidal volume strategies might benefit patients not diagnosed with ARDS, like patients at risk for ALI or receiving mechanical ventilation. A 2013 qualitative systematic review evaluated low tidal volume strategy versus traditional tidal volume strategy. It found support for using a low tidal volume strategy—sometimes in terms of cytokine release, sometimes in terms of actual outcomes and other measurements—concluding that benefits of low tidal volume strategies outweigh the traditional tidal volume strategy of greater than 10 cc/kg.

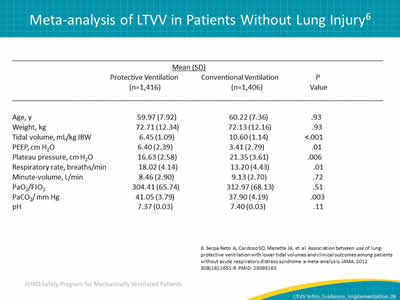

Slide 26: Meta-analysis of LTVV in Patients Without Lung Injury

Say:

In 2012, Nito et al. published a meta-analysis reviewing studies that compared a lung protective strategy of low tidal volume with a conventional ventilation strategy. Both the lung protective group and the conventional ventilation group each included about 1,400 patients. While weight average was similar across the groups, tidal volume was different. The average tidal volume was 6.45 mL/kg of the patient’s predicted body weight for protective ventilation versus more than 10 mL/kg of the patient’s predicted body weight for conventional ventilation.

PEEP was much higher in the lung protective strategy, much like the ARDSNet study found. Plateau pressures were significantly lower. Respiratory rates were a little higher, but the other parameters did not show any major change. Arterial CO2 was higher in the lung protective strategy compared with the standard conventional ventilation strategy, though this wasn’t a statistically significant result. There was also no significant difference in pH across the two groups.

Ask:

So what do this data tell us?

What did the meta-analysis find?

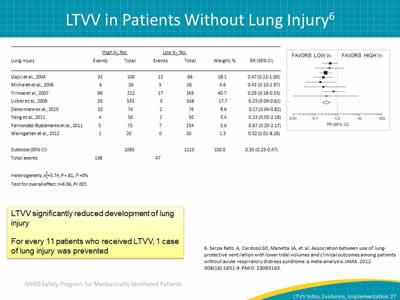

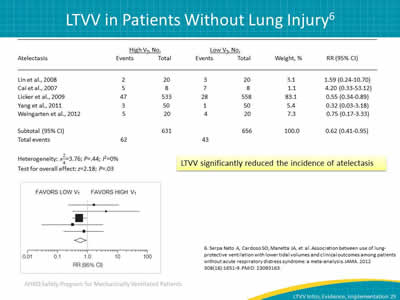

Slide 27: LTVV in Patients Without Lung Injury

Say:

By comparing patients receiving a low tidal volume strategy with patients receiving the conventional strategy, we find significant benefits. Looking at the plot in the lower right corner of the slide, you’ll see a diamond sitting squarely on the left side of the central dotted line, also called the line of identity. This is a statistically significant indication that the low tidal volume strategy reduces lung injury compared with standard ventilation. Based on this analysis, a low tidal volume strategy prevents 1 in every 11 cases involving additional lung injury.

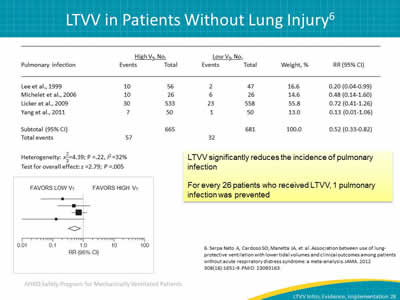

Slide 28: LTVV in Patients Without Lung Injury

Say:

These studies also evaluated additional parameters. One parameter involved mechanically ventilated patients who developed a pulmonary infection. As shown in the plot graph, the diamond that pulls the data together lands squarely on the side that favors the low tidal volume strategy. Based on this analysis, for every 26 patients that receive a low tidal volume strategy, you will prevent 1 associated pulmonary infection.

Slide 29: LTVV in Patients Without Lung Injury

Say:

The diamond for the atelectasis parameter also sits squarely on the side favoring the low tidal volume strategy without touching the central line of identity. This shows LTVV is effective in preventing atelectasis, based on the analyzed studies. It’s important to remember that the low tidal volume strategy used in all studies of this meta-analysis used PEEP. Avoiding ZEEP is a crucial component of the low tidal volume strategy and key to improving patient outcomes.

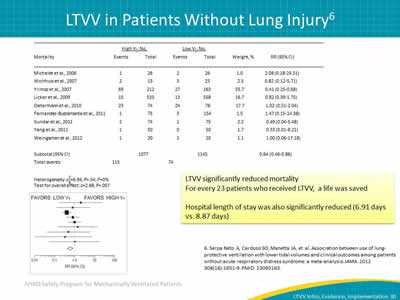

Slide 30: LTVV in Patients Without Lung Injury

Say:

The diamond for the mortality parameter, like the diamonds for the other parameters, lands squarely on the side favoring low tidal volume strategy. Based on this analysis, for every 23 patients who get the low tidal volume strategy using PEEP, one life is saved. Hospital length of stay was also significantly reduced.

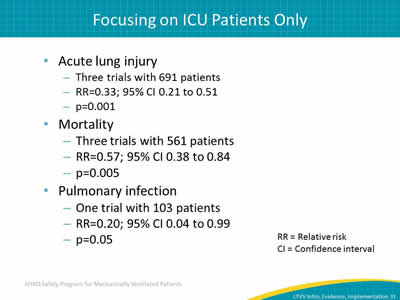

Slide 31: Focusing on ICU Patients Only

Say:

The data concerning ICU patients show statistically significant improvements in lung injury, mortality, and pulmonary infection rates. These data result from mechanically ventilated patients who are at risk for ARDS but do not meet the criteria for ARDS. These data are powerful and suggest that we can prevent the progression to ARDS by implementing the low tidal volume strategy early in patients’ care.

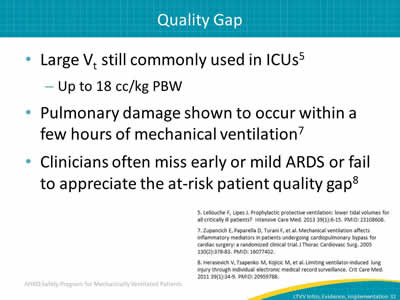

Slide 32: Quality Gap

Say:

Currently, values of up to 18 cc/kg of predicted body weight are sometimes used in ICUs. Based on the data, pulmonary damage can occur within a few hours or minutes of mechanical ventilation. Despite their best efforts, clinicians either miss the early or mild signs of ARDS or fail to appreciate the high-risk patient groups. This lack of awareness contributes to a large quality gap, one clinicians may not understand or see as detrimental. A preemptive strategy is required to close this quality gap.

Slide 33: Low Tidal Volume Implementation

Say:

We will now discuss how to implement low tidal volume ventilation strategies in the acute care setting.

Slide 34: Preemption

Say:

Instead of waiting for a patient to develop ARDS, prevent this progression. Once a patient meets the criteria for ARDS, damage has already begun. The photo on the slide illustrates the cliché that the train has left the station. Therefore, initiate the low tidal volume strategy to minimize the risk for all patients receiving mechanical ventilation, because even a few hours using a large tidal volume may be enough to start the cascade into serious lung injury.

Slide 35: Low Tidal Volume Implementation

Say:

A 2013 study reviewed patients undergoing relatively major abdominal surgery and receiving mechanical ventilation for between 4 and 5 hours. Patients who received a low tidal volume strategy using PEEP settings had statistically significant improvements in a variety of parameters, including pulmonary complications and length of stay, when compared with standard tidal volume ventilation.

Slide 36: Low Tidal Volume Implementation

Say:

The preemptive strategy for preventing lung injury and the progression of ARDS recommends ventilating the patient somewhere between 6 to 8 cc/kg of their predicted body weight. Based on previous studies and publications, tidal volumes of this size also eliminate most hypercarbia complications.

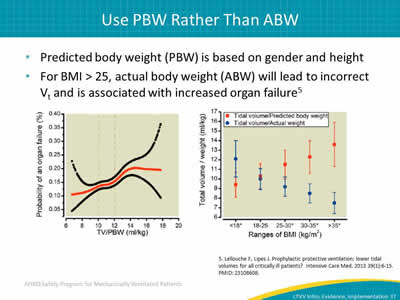

Slide 37: Use PBW Rather Than ABW

Say:

To recap, predicted body weight is based on gender and height. The graph on the left shows that the probability of an organ failure increases dramatically as the tidal volume per predicted body weight ratio increases.

When applying the low tidal volume strategy, it’s important to have a process in place through which your ICU can accurately determine the patient’s predicted body weight. You also should have a process dedicated to accurately measuring the patient’s height. It may be as simple as providing disposable tape measures in patient rooms and including height as part of routine ventilator charting. When a patient is admitted, the nurses or the respiratory therapist can measure the height, and then record in the electronic health record to track tidal volume per predicted body weight.

Slide 38: What about Positive End-Expiratory Pressure?

Say:

As mentioned earlier, low tidal volume causes atelectasis, as suggested in Bendixon’s research. However, this occurs only when it’s used without PEEP. PEEP counteracts this tendency, especially in cases of obesity. It also prevents atelectrauma in which the alveoli snap open and closed. It’s strongly recommended that we use PEEP settings and avoid using ZEEP when we apply low tidal volume strategy to all mechanically ventilated patients.

Even after reviewing the studies that have shown benefits of low tidal volume mechanical ventilation in patients at risk for but free of ARDS, it’s difficult to know what the right PEEP value should be. Some studies use 5 while others use 6 or 8. Some have even used a PEEP value as high as 12, and some ARDS studies use PEEP values over 20. It remains unclear in the literature what the exact number should be. However, we do know that a value below 5 is problematic. Any PEEP below 5 is essentially the same as ZEEP, which we are trying to avoid. The minimum value should be 5, and studies support a range of acceptable PEEP values above 5.

Of note, you should use the ARDSNet protocol if ARDS is diagnosed in a patient.

Slide 39: What about PEEP?

Say:

A ZEEP value, as mentioned earlier, is generally considered anything below 5 and is associated with such negative outcomes as hypoxia, ventilator-associated pneumonia, and increased mortality. While additional research is needed to ascertain the optimum value (and the optimum value is likely patient-specific), target a PEEP value of at least 5 or greater for patients receiving mechanical ventilation.

Slide 40: Respiratory Rate

![Using Low Vt may require increased respiratory rates to prevent excessive hypercarbia. Permissive hypercapnia (partial pressure of carbon dioxide [pCO2] in the 50s) may be needed: Usually tolerated well unless there is also a severe metabolic acidosis. Maintain minute ventilation as best as possible. May need to increase to 30 breaths per minute or more. Potential downsides with these high rates include breath-stacking and high auto-PEEP.](/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/professionals/quality-patient-safety/hais/tools/mvp/modules/technical/ltvv-intro/ltvv-intro-slide40.jpg)

Say:

The low tidal volume strategy sometimes requires an approach that will lead to a higher respiratory rate. The meta-analysis we examined earlier showed that for patients receiving the low tidal volume strategy, the average respiratory rate was higher. This is used to prevent excessive hypercarbia. With tidal volumes in the 6 to 8 cc/kg range, the need for permissive hypercapnia is unlikely, although tolerated well by most patients. In general, try to maintain adequate minute ventilation, although you may need to increase to 30 breaths per minute or more.

There are some downsides associated with high respiratory rates, such as auto-PEEP and breath-stacking. These issues will require the attention of and partnership with your respiratory therapist and physicians to adjust the ventilator. Fortunately, these problems are not common for most patients.

Slide 41: Plateau Pressure

Say:

Plateau pressure is another key element of a low tidal volume strategy, specifically for ARDS prevention and treatment strategy. Plateau pressure is a pressure measured in the lungs after the end of inspiration, when the lungs have come to a static, inflated state. Keeping this value below 30 centimeters of water has been shown to prevent lung injury and improve patient outcomes. You may need to use the lower end of the low tidal volume strategy for patients with stiff lungs, using the 6 to 8 cc/kg range or even the ARDSNet range of 4 to 6 cc/kg to keep the plateau pressure down. Occasionally, bronchodilators, sedation, or even more rarely, paralysis, may be necessary to get control of this value. Heavy sedation and paralysis should be used very rarely.

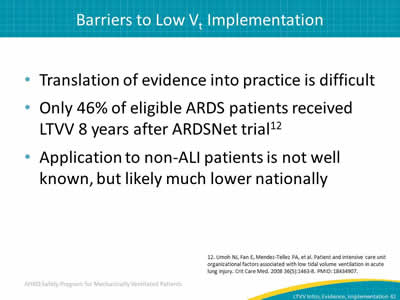

Slide 42: Barriers to Low Vt Implementation

Say:

We know that translating evidence into practice is often difficult. In fact, 8 years after the 2008 ARDSNet trial was published, a study was released asking, "How many people are using this lifesaving strategy?" Only about 46 percent of the patients who had the diagnosis of ARDS on their charts were actually getting some sort of lung protective strategy, particularly the ARDSNet strategy, in order to try to improve their outcome. The application of LTVV to non-ARDS patients is not well known, but it is reasonable to expect that it is much lower nationally.

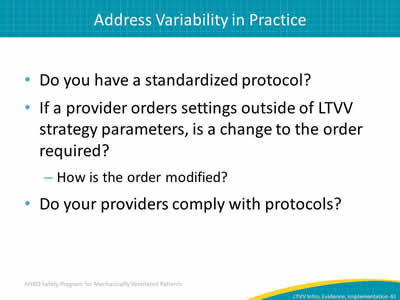

Slide 43: Address Variability in Practice

Say:

We want to use principles of patient safety and quality in implementing LTVV. One of the biggest issues we face in patient safety and quality is variability in practice. With so many different people of different professions working so close together, there is a high potential for variability across people's practices.

However, a substantial amount of variability, deviating from what the literature says is the best practice, can widen the quality gap. As a result, the patient doesn't get the therapy that the evidence suggests that they should. Trying to reduce variability in practice is a crucial element to improving patient safety.

One of the best ways to reduce variability is to sit down with stakeholders and try to reach an agreement on a standardized protocol that you can apply in your unit. Creating this standardized protocol may have challenges. If, for example, a provider writes orders that are not consistent with the LTVV strategy, you must decide whether a change or variable order is required. You should also consider how the order is modified from the standardized protocol you wish to establish. While it may take quite some time to reach an agreement, reducing variability in practice is important and is worth the time and energy it takes to achieve.

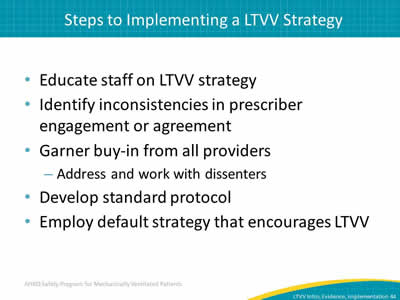

Slide 44: Steps to Implementing a LTVV Strategy

Say:

Educating staff on the LTVV strategy is an essential first step in implementing LTVV, but it is insufficient by itself. Simply educating people on the concepts of low tidal volume strategy and providing them with data is not enough to motivate action. Some forms of education are more effective than others, however, so attempts to implement a new strategy will be much more effective if you develop creative educational approaches to bring the information to your staff.

You should also identify inconsistencies in prescriber engagement or agreement. If you find that there are certain providers who consistently fail to implement the low tidal volume strategy, you need to engage them and discover the reasons for this inconsistency. They may need more information, or perhaps they don't understand or disagree with a development in the strategy. Identify those dissenters and engage them, as dissenters can have a huge amount of valuable information to help you improve the implementation of your strategy.

Garner buy-in from all of your providers by finding a middle ground where everybody can agree on an approach. This will help to close the quality gap by developing a standard protocol encouraging the LTVV strategy. Develop a process in which nurses can accurately measure a patient's height and make that information widely accessible. Developing a standard protocol and establishing LTVV as a default strategy will also greatly improve your implementation of LTVV.

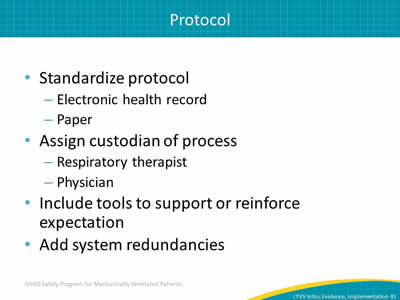

Slide 45: Protocol

Say:

Standardizing protocol is necessary so that daily practices are assessed and reassessed on an ongoing basis. This can be facilitated through using electronic health records and paper charts. This record will alert a prescriber to the recommended tidal volume for a patient that has just begun using LTVV. It’s necessary to check this record every day in case of sudden changes.

Another important measure to standardizing protocol is assigning a custodian of the process. This person will run the process honestly and efficiently. A custodian of the process is generally either a respiratory therapist or a physician. Respiratory therapists are usually at the center of the process as they are usually responsible for applying and maintaining ventilator settings. They can also be the intermediary between the measurements that the nurses need. While you may alternatively decide that you want a physician to be the custodian of the process, respiratory therapists are knowledgeable about bedside ventilator management, and will likely be useful assets to the physician custodian.

You should also include tools to support or reinforce your expectations, such as daily goal checklists with an assessment for whether or not the patient meets low tidal volume strategy. Finally, you should add system redundancies that will be consistent and keep the project going.

Slide 46: Closing Gaps in Quality

Say:

Closing gaps in quality is crucial, and auditing your intervention practices is an essential step in doing so. You should create a process using the LTVV data collection tool whereby you audit your practices intermittently. For instance, every two months of an entire calendar year, you might spend a week assessing how many of your patients achieved the low tidal volume strategy or adhered to your standardized protocol. Such an auditing process will sample the collected data and provide you with enough information as to how your patients are doing in general. Review that data and input it to your Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program (CUSP) graphs and tables (consult the Module To Use CUSP for Mechanically Ventilated Patients). Print out those graphs and tables to share them with your CUSP team so that they know how efforts toward improving the process are going.

Slide 47: Summary

Say:

The low tidal volume strategy is necessary for patients with ALI and ARDS. The emerging evidence says it’s also probably necessary for non-ALI/ARDS ICU patients, as well as those in the operating room. Essentially, every patient receiving mechanical ventilation, even for a short period of time, deserves a low tidal volume strategy. This strategy includes a tidal volume between 6 to 8 cc/kg or less, as well as an avoidance of ZEEP, in order to optimize their outcomes.

To recap, targeting plateau pressure, avoiding ZEEP, and keeping a PEEP value of at least 5 or higher are the best ways to implement the low tidal volume strategy.

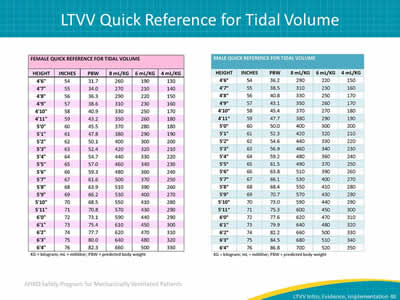

Slide 48: LTVV Quick Reference for Tidal Volume

Say:

This is a quick reference chart for tidal volume. It provides a numerical nomogram to select tidal volumes based on predicted body weight. These quick reference cards are ready to print for use in your unit and can be found in the LTVV Data Collection Tool located on the AHRQ Web site (Word File, 688 KB).

Slide 49: Questions?

Ask:

Are there any questions?

Slide 50: References

Slide 51: References

Slide 52: References