Ventilator-Associated Event Surveillance: Slide Presentation

AHRQ Safety Program for Mechanically Ventilated Patients

Slide 1: AHRQ Safety Program for Mechanically Ventilated Patients

Ventilator-Associated Event Surveillance

Slide 2: Learning Objectives

After this session, you will be able to—

- Discuss the ramifications of ventilator-associated events (VAEs).

- Describe methods to evaluate VAEs.

- Understand the implications of objective VAE surveillance.

- Identify ways to use data to drive improvement.

Slide 3: Why Collect VAE Data?

- Collecting VAE data can be used to—

- Connect the dots to harm.

- Avoid failure of infection prevention efforts due to "silo mentality."

- View interventions under the larger context of patient safety.

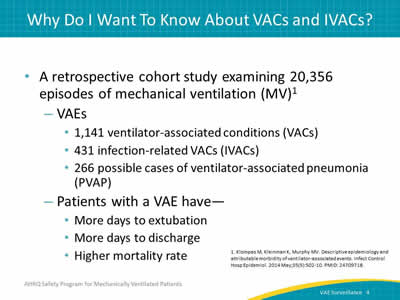

Slide 4: Why Do I Want To Know About VACs and IVACs?

- A retrospective cohort study examining 20,356 episodes of mechanical ventilation (MV):1

- VAEs:

- 1,141 ventilator-associated conditions (VACs).

- 431 infection-related VACs (IVACs).

- 266 possible cases of ventilator-associated pneumonia (PVAP).

- Patients with a VAE have—

- More days to extubation.

- More days to discharge.

- Higher mortality rate.

- VAEs:

1. Klompas M, Kleinman K, Murphy MV. Descriptive epidemiology and attributable morbidity of ventilator-associated events. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2014 May;35(5):502-10. PMID: 24709718.

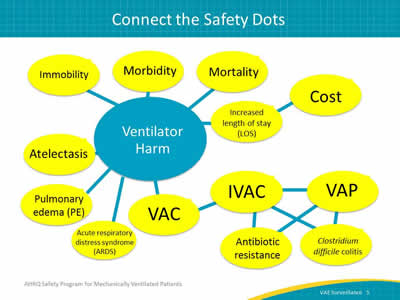

Slide 5: Connect the Safety Dots

Image: Graphic showing the various harms that can result from mechanical ventilation.

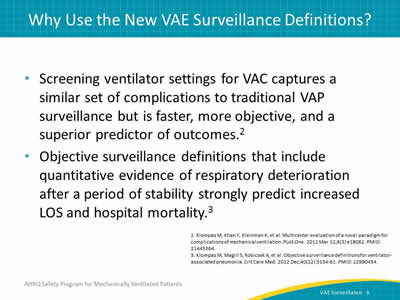

Slide 6: Why Use the New VAE Surveillance Definitions?

- Screening ventilator settings for VAC captures a similar set of complications to traditional VAP surveillance but is faster, more objective, and a superior predictor of outcomes.2

- Objective surveillance definitions that include quantitative evidence of respiratory deterioration after a period of stability strongly predict increased LOS and hospital mortality.3

2. Klompas M, Khan Y, Kleinman K, et al. Multicenter evaluation of a novel paradigm for complications of mechanical ventilation. PLoS One 2011 Mar 22;6(3):e18062. PMID: 21445364.

3. Klompas M, Magill S, Robicsek A, et al. Objective surveillance definitions for ventilator-associated pneumonia. Crit Care Med 2012 Dec;40(12):3154-61. PMID: 22990454.

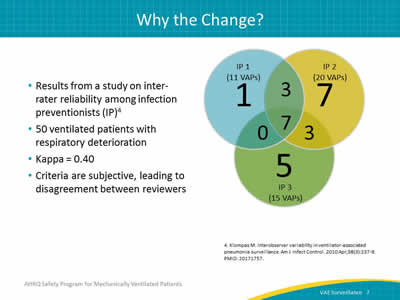

Slide 7: Why the Change?

- Results from a study on inter-rater reliability among infection preventionists (IP).4

- 50 ventilated patients with respiratory deterioration.

- Kappa = 0.40.

- Criteria is subjective leading to disagreement between reviewers.

Image: A Venn diagram showing the interrater reliability for adjudicating traditional VAP surveillance.

4. Klompas M. Interobserver variability in ventilator-associated pneumonia surveillance. Am J Infect Control 2010 Apr;38(3):237-9. PMID: 20171757.

Slide 8: Why the Shift?

- Broaden the focus:

- Shifting focus of surveillance from pneumonia alone to complications in general emphasizes the importance of preventing all complications of MV, not just pneumonia.

- When definitions are objective, caregivers can focus on what went wrong rather than debate the definition.

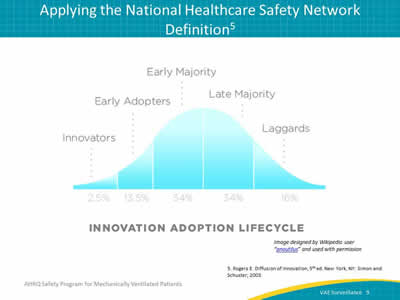

Slide 9: Applying the National Healthcare Safety Network Definition5

Image: Rogers' diffusion of innovation adoption lifecycle.

Image designed by Wikipedia user "pnautilus" and used with permission.

5. Rogers E. Diffusion of innovation, 5th ed. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster; 2003.

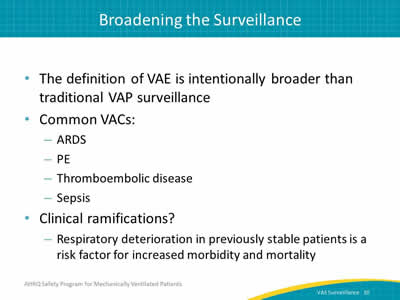

Slide 10: Broadening the Surveillance

- The definition of VAE is intentionally broader than traditional VAP surveillance.

- Common VACs:

- ARDS.

- PE.

- Thromboembolic disease.

- Sepsis.

- Clinical ramifications?

- Respiratory deterioration in previously stable patients is a risk factor for increased morbidity and mortality.

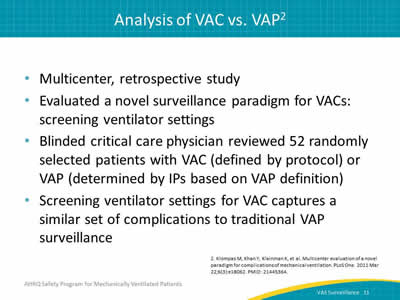

Slide 11: Analysis of VAC vs. VAP2

- Multicenter, retrospective study.

- Evaluated a novel surveillance paradigm for VACs: screening ventilator settings.

- Blinded critical care physician reviewed 52 randomly selected patients with VAC (defined by protocol) or VAP (determined by IPs based on VAP definition).

- Screening ventilator settings for VAC captures a similar set of complications to traditional VAP surveillance.

2. Klompas M, Khan Y, Kleinman K, et al. Multicenter evaluation of a novel paradigm for complications of mechanical ventilation. PLoS One 2011 Mar 22;6(3):e18062. PMID: 21445364.

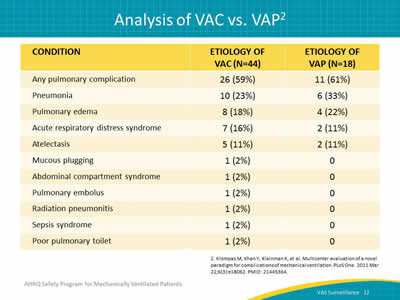

Slide 12: Analysis of VAC vs. VAP2

Image: Table of patients flagged with ventilator-associated complications of ventilator-associated pneumonia.

2. Klompas M, Khan Y, Kleinman K, et al. Multicenter evaluation of a novel paradigm for complications of mechanical ventilation. PLoS One 2011 Mar 22;6(3):e18062. PMID: 21445364.

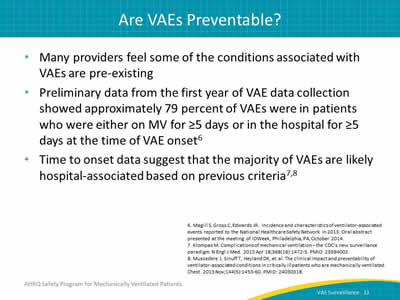

Slide 13: Are VAEs Preventable?

- Many providers feel some of the conditions associated with VAEs are pre-existing.

- Preliminary data from the first year of VAE data collection showed approximately 79 percent of VAEs were in patients who were either on MV for ≥5 days or in the hospital for ≥5 days at the time of VAE onset.6

- Time to onset data suggest that the majority of VAEs are likely hospital-associated based on previous criteria.7,8

6. Magill S, Gross C, Edwards JR. Incidence and characteristics of ventilator-associated events reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network in 2013. Oral abstract presented at the meeting of IDWeek, Philadelphia, PA, October 2014.

7. Klompas M. Complications of mechanical ventilation—the CDC’s new surveillance paradigm. N Engl J Med 2013 Apr 18;368(16):1472-5. PMID: 23594002.

8. Muscedere J, Sinuff T, Heyland DK, et al. The clinical impact and preventability of ventilator-associated conditions in critically ill patients who are mechanically ventilated. Chest 2013 Nov;144(5):1453-60. PMID: 24030318.

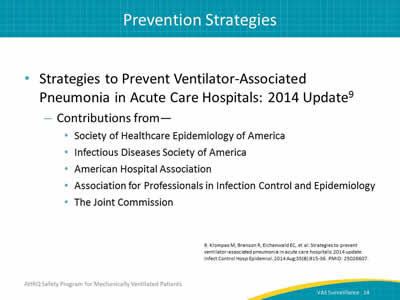

Slide 14: Prevention Strategies

- Strategies to Prevent Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia in Acute Care Hospitals: 2014 Update:9

- Contributions from—

- Society of Healthcare Epidemiology of America.

- Infectious Diseases Society of America.

- American Hospital Association.

- Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology.

- The Joint Commission.

- Contributions from—

9. Klompas M, Branson R, Eichenwald EC, et al. Strategies to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia in acute care hospitals: 2014 update. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2014 Aug;35(8):915-36. PMID: 25026607.

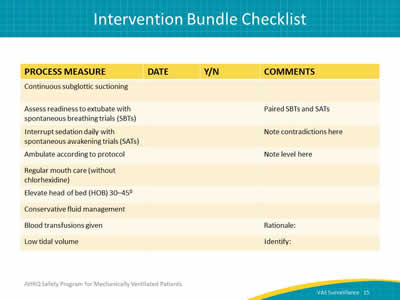

Slide 15: Intervention Bundle Checklist

Image: Table listing items in the Intervention Bundle Checklist.

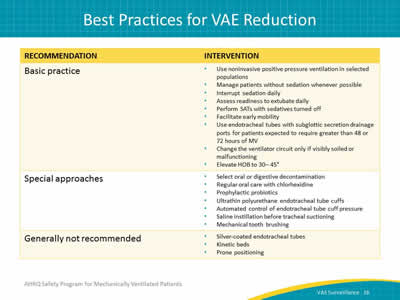

Slide 16: Best Practices for VAE Reduction

Image: Table with best practices for VAE reduction.

Slide 17: What About Oral Care With Chlorhexidine?

- Routine oral care with chlorhexidine:10

- Prevents nosocomial pneumonia in cardiac surgery patients.

- May not decrease VAP risk in noncardiac surgery patients.

- Does not affect—

- Mortality.

- Duration of MV.

- Intensive care unit (ICU) LOS.

10. Klompas M, Speck K, Howell MD, et al. Reappraisal of routine oral care with chlorhexidine gluconate for patients receiving mechanical ventilation: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2014 May;174(5):751-61. PMID: 24663255.

Slide 18: VAE Prevention Techniques

- Prevent pneumonia by implementing HOB elevation.

- Avoid pulmonary complications through fluid conservation.

- Protect against atelectasis by managing sedation.

- Combat acute lung injury by following a low tidal volume ventilation strategy.

Slide 19: Getting Started on Prevention

Where to start?

- Look at both process and outcome measures.

- Track your own performance over time.

- Do we see improvements?

Image: Photo of a large "start" button.

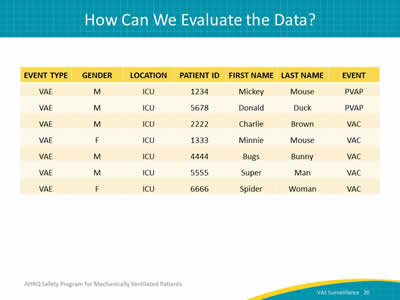

Slide 20: How Can We Evaluate the Data?

Image: Table (line list) of fictional example patient information regarding VAEs.

Slide 21: How Will I Use My Data To Drive Improvement?

- Review both individual cases and system level issues.

- Develop a form to help analyze individual cases.

- Do we have policies and procedures in place?

- Do we follow evidence-based guidelines?

- Are we consistent with our practices?

Slide 22: Review All VAC Cases—Case Review 1

- Patient develops a VAC:

- Chronic ventilator dependency.

- Ambulation protocols were not implemented.

- Not monitored for dehydration.

- Presence of sputum not documented.

- Lack of communication between nursing and respiratory groups.

Slide 23: Case Review 2

- Ms. X is a 76-year-old woman, admitted to the ICU with septic shock requiring large volume fluid resuscitation:

- Intubated and placed on ventilator.

- Stable until day 6 when she has progressive oxygenation demands.

- Increased demands last for 72 hours.

Slide 24: Case Review 2—Outcomes

- Patient has a VAC:

- No fever.

- No increased white blood cell count.

- No new antibiotics.

- Diagnosis: Pulmonary edema.

- Opportunities for improvement?

Slide 25: Case Review 3

- In an example ICU, many VAEs are PVAPs.

- Evaluation:

- Head of bed monitoring.

- Suctioning frequency.

- SATs.

- Endotracheal tubes with subglottic suctioning.

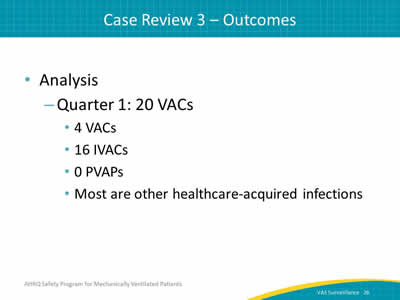

Slide 26: Case Review 3—Outcomes

- Analysis:

- Quarter 1: 20 VACs:

- 4 VACs.

- 16 IVACs.

- 0 PVAPs.

- Most are other healthcare-acquired infections.

- Quarter 1: 20 VACs:

Slide 27: Opportunities for Improvement

- Hardwire ambulation protocols.

- Ensure documentation of secretions.

- Work collaboratively with respiratory therapists to identify subtle changes.

- Daily huddles.

Slide 28: Know Your Data

"Surveillance is a critical component of every quality improvement effort; you cannot prevent it if you cannot measure it."

—Linda Greene, R.N., M.P.S., CIC

Infection Prevention Manager

University of Rochester Medical Center, Highland Hospital

Slide 29: The Bottom Line

- VAEs are associated with increased mortality and ICU and hospital LOS.

- In randomized controlled trials, VAP interventions have been shown to improve objective outcomes, such as duration of MV, ICU or hospital LOS, mortality, and costs.

- The existing VAP prevention literature is the best available guide to improving outcomes for ventilated patients.

- It is important to continue monitoring the processes of care and the outcomes for mechanically ventilated patients.

- Always give feedback to providers and assess the potential for preventable events.

Slide 30: Questions?

Image: Colored hanging tags with questions marks on them.

Slide 31: References

1. Klompas M, Kleinman K, Murphy MV. Descriptive epidemiology and attributable morbidity of ventilator-associated events. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2014 May;35(5):502-10. PMID: 24709718.

2. Klompas M, Khan Y, Kleinman K, et al. Multicenter evaluation of a novel paradigm for complications of mechanical ventilation. PLoS One 2011 Mar 22;6(3):e18062. PMID: 21445364.

3. Klompas M, Magill S, Robicsek A, et al. Objective surveillance definitions for ventilator-associated pneumonia. Crit Care Med 2012 Dec;40(12):3154-61. PMID: 22990454.

4. Klompas M. Interobserver variability in ventilator-associated pneumonia surveillance. Am J Infect Control 2010 Apr;38(3):237-9. PMID: 20171757.

5. Rogers E. Diffusion of innovation, 5th ed. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster; 2003.

Slide 32: References

6. Magill S, Gross C, Edwards JR. Incidence and characteristics of ventilator-associated events reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network in 2013. Oral abstract presented at the meeting of IDWeek, Philadelphia, PA, October 2014.

7. Klompas M. Complications of mechanical ventilation—the CDC’s new surveillance paradigm. N Engl J Med 2013 Apr 18;368(16):1472-5. PMID: 23594002.

8. Muscedere J, Sinuff T, Heyland DK, et al. The clinical impact and preventability of ventilator-associated conditions in critically ill patients who are mechanically ventilated. Chest 2013 Nov;144(5):1453-60. PMID: 24030318.

9. Klompas M, Branson R, Eichenwald EC, et al. Strategies to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia in acute care hospitals: 2014 update. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2014 Aug;35(8):915-36. PMID: 25026607.

10. Klompas M, Speck K, Howell MD, et al. Reappraisal of routine oral care with chlorhexidine gluconate for patients receiving mechanical ventilation: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2014 May;174(5):751-61. PMID: 24663255.