Learning From Defects Through Sensemaking: Facilitator Notes

AHRQ Safety Program for Surgery

Slide 1: Learning From Defects Through Sensemaking

Say:

This module focuses on the process of Learning From Defects Through Sensemaking.

Slide 2: Learning Objectives

Say:

At the end of this module, you will be able to–

- Describe the difference between first-order and second-order problem solving;

- List contributing factors that make defects in care more likely to occur; and,

- Use the Learning From Defects, or LFD, tool to perform second-order problem solving.

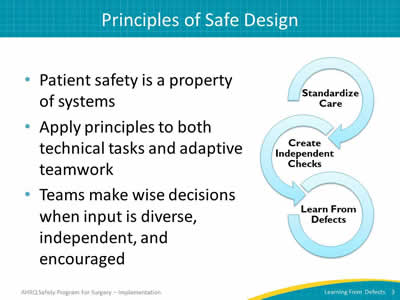

Slide 3: Principles of Safe Design

Say:

The principles of safe design apply to the two main pieces of the surgical quality work: technical tasks, e.g., prepping the skin or choosing the appropriate antibiotic; and the adaptive teamwork, i.e., how to make sure that the technical pieces are performed correctly.

The principles of safe design include three major elements:

- Standardization of care

- Independent checks to support that care, and

- Learning from defects.

Learning from defects is one way to improve the design of systems, and patient safety is a property of that system. The LFD tool does not blame individuals, but seeks root causes of errors. It supports the discovery process essential to prevent repeat errors and implement interventions.

Teams make wise decisions when the input is diverse, independent, and strongly encouraged. When organizing your team, make sure it includes various practitioners (nurses, anesthesiologists, certified registered nurse anesthetists, surgeons, and environmental services personnel). Include everyone who might have a stake in the patient care process. Listen to their suggestions.

Ask:

Have you established your surgical quality team?

What types of practitioners are in your group?

What types of practitioners will you reach out to?

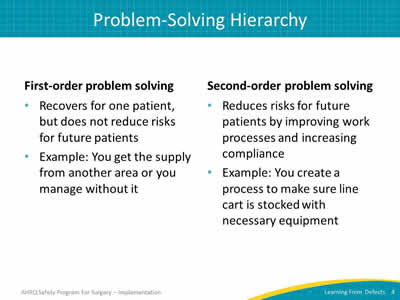

Slide 4: Problem-Solving Hierarchy

Say:

First-order problem solving resolves an issue for one patient, but does not reduce the systematic risk that exists for future patients. First-order problem solving is what we do every day: We find that something is not working, and we develop a workaround or a quick solution.

For example, if you are missing a required supply or piece of equipment, you may borrow it from another department or another room. While this fixes the immediate problem for your patient, it does not prevent the need for a future workaround. In fact, that workaround may actually harm another patient, now impacted by the missing supply or equipment. While the immediate fix may be heroic under emergent circumstances, it doesn’t prevent problems from happening in the future. The system remains the same, at risk for harming a patient.

Instead of relying on first-order problem solving, practice second-order problem solving. Second-order problem solving focuses on identifying system issues rather than one-time solutions.

In the example above, the reallocated equipment prevented harm for one patient. The next step recognizes that the system should not put clinicians in a situation where they must borrow from one area or patient to meet the needs of another.

Ask:

What led to the need to search and borrow the missing supply or equipment?

What interventions can be put in place to ensure necessary supplies are available?

Activity:

What are your examples of first-order problem solving?

How can you translate this into second-order problem solving?

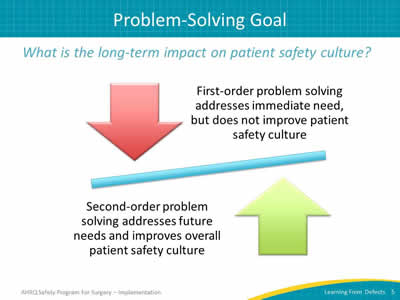

Slide 5: Problem-Solving Goal

Say:

First-order problem solving doesn’t encourage a positive patient safety culture. In fact, it often leaves staff frustrated and feeling that the system isn’t working.

Ask:

Why do they have to rely on a temporary procedure to take care of a patient?

Does the same fix happen for all patients, all caregivers, and all shifts?

Say:

Second-order problem solving addresses future needs and improves the overall patient safety culture.

Slide 6: What is a Defect?

Ask:

What is a defect?

Say:

A defect is anything you do not want to have happen again or ever have happen, even if it hasn’t happened yet. A defect can be a specific harm to a patient. A defect is also something that the nurses or the surgeons find frustrating, because it affects their workflow and could lead to future patient harm.

Ask:

Can you give an example of a defect in your unit?

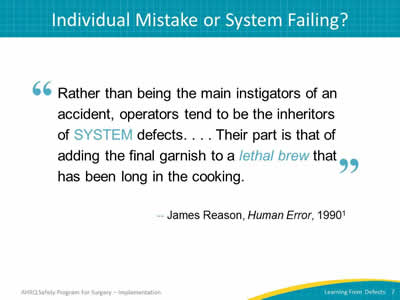

Slide 7: Individual Mistake or System Failing?

Say:

Historically, defects in medicine have been subject to accusation, criticism, and denial. In fact, James Reason in his seminal book Human Error, published in 1990, pointed out that individuals are not to blame for system defects. He wrote that rather than being the main instigators of an accident, operators or the frontline staff members are the inheritors of system defects.

When it appears that an individual has made a mistake, review the system; how did that individual get into the position where the mistake occurred? No one comes to work with the intent to harm a patient. We want to help patients. Your colleagues want to help people get better. So, first look at the system and analyze why the mistake occurred. This is an essential component of the Learning From Defects process. It moves away from an accusatory mentality and toward a systems approach.

Slide 8: Source of Defects

Say:

You can find defects in many places. Adverse-event reporting systems are common in hospitals. Sentinel events, as defined by The Joint Commission, or any claims data from your legal department provide high-profile defects. Infection rates from hospital epidemiology and infection prevention also present known complications.

But the most effective way to identify defects, particularly in a localized environment like the operating room, also empowers your frontline providers. Ask them. The Perioperative Staff Safety Assessment (PSSA) is a simple two-question survey. As a reminder, the two questions are listed:

- How will the next patient be harmed or get a surgical site infection (SSI)?

- What can you do to prevent this harm or SSI?

The PSSA adapts the Staff Safety Assessment by adding SSI. It can be administered at any frequency and with any level of technology that suits your unit and team: electronic surveys each quarter (high-tech) to always-available suggestion box style (low-tech).

Ask your operating room technicians, ask your operating room nurses, ask your anesthesiologists: How are we going to harm the next patient? Or if your team is focused on SSIs: How is the next patient going to get an SSI? What can we do locally with our frontline staff in our unit to prevent or minimize that harm?

Adverse reporting systems, sentinel events, and claims data are reactive—the unfortunate event has already occurred. The PSSA is proactive. It asks frontline providers to think ahead and taps into their wisdom to prevent patient harm from happening.

Ask:

Who has administered the Staff Safety Assessment to their frontline staff?

If you have administered it, have you started to work on a defect identified?

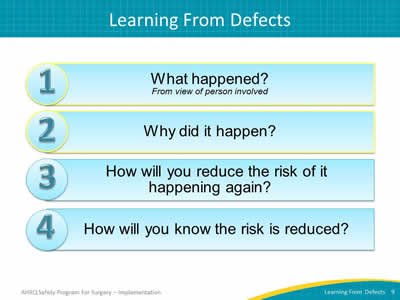

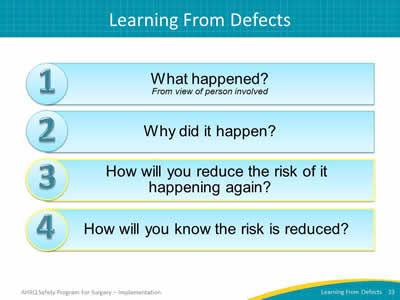

Slide 9: Learning From Defects

Say:

The Learning From Defects tool asks four main questions:

- What happened?

- Why did it happen?

- How will you reduce the risk of it happening again?

- How will you know the risk is reduced?

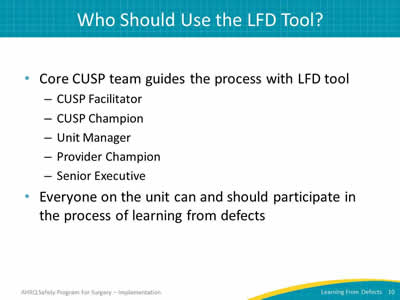

Slide 10: Who Should Use the LFD Tool?

Say:

The core surgical quality team guides the use of the Learning from Defects tool. This team includes the team’s facilitator, champion, unit manager, provider champion, and the senior executive. Everyone in the operating room, from preoperative to post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) staff, can and should participate in the Learning from Defects process.

Slide 11: Check Your Assumptions

Say:

When forming your surgical quality team, bring a diverse group of colleagues together. In addition to operating room nurses and physicians, include colleagues from preoperative and PACU areas. If you suspect the problem being tackled involves defects in the general ward, include your general ward colleagues in the process. Talk to your team to identify all stakeholders. Your core Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program, or CUSP, team will need to augment the team with representatives that correspond to the defect being addressed.

Once the appropriate team has been assembled, do not assume everyone is aware of the nuances of the problem. Encourage everyone to ask questions. Once you have a firm grasp on the defect, take the time to describe the entire situation. Undoubtedly, those diverse team members can point out aspects of the defect that you may not have appreciated.

Another way to ensure that each team member understands the full nature of the defect(s). The best way to do this is to walk the process with the frontline staff. Let them show you their experience.

Slide 12: What Happened?

Say:

What is walking the process? This is a robust method for determining how the defect happened. The surgical quality team puts itself in the place of those involved; it gets in the middle of the event as it unfolds.

Listen to colleagues during this process. Seek to understand the process; don’t judge the individuals. Move away from the tendency to accuse, blame, criticize, or deny. Instead, focus on what happened and what contributed to the event.

Ask clarifying and followup questions. When things aren’t clear or when two pieces of information seem to contradict each other, ask more questions. Try to find out what exactly led to the defect. Explore both the reasoning and the emotions behind what happened.

Ask:

Why were the decisions made?

Say:

Individuals may have been put into a particular position where certain defects were sure to happen. Remember, the operators in a defect are often put into a position leading to patient harm because of the system. Your team must understand their reasoning and how they reacted to understand the defect. Don’t just assume that an individual made one mistake. The full situation, and in fact the system, might have made the mistake almost inevitable.

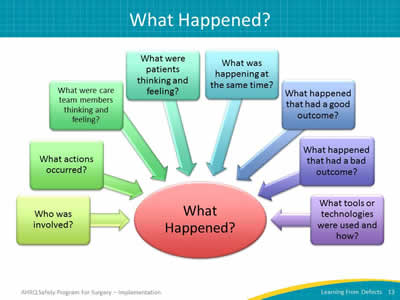

Slide 13: What Happened?

Say:

Ask many questions.

Ask:

Who was involved?

What actions occurred?

What were the team members thinking and feeling?

Say:

If the patient was part of the defect process (e.g., alert, rather than under anesthesia), ask the patient what they were thinking or feeling when the defect occurred. Bring them into the process, if appropriate. The patient will have a different perspective that can shed light on why the defect occurred.

Ask:

What was happening at the same time?

What happened that prevented the defect?

What happened that resulted in the defect?

What tools and technologies were used?

Were they used properly?

Say:

These are the types of questions to ask to understand how a defect occurred. Try to find out exactly how things occurred in real time.

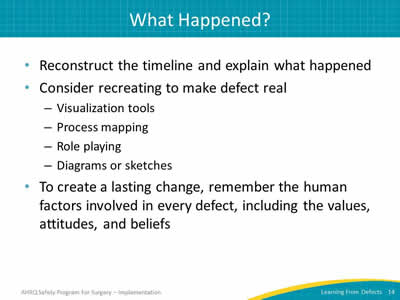

Slide 14: What Happened?

Say:

Your surgical quality team can reconstruct the timeline of the defect based on those questions. Explain what happened. Make it visual. Use Lean Six Sigma tools to visualize and map the process (for example, the spaghetti diagram). Simulate the process that led to the defect. Create diagrams or sketches to re-create the exact situation and better understand the details that contributed to the defect.

To create a lasting change, remember the human factors involved in the defect: the attitudes, the values, and the beliefs. Those human factors will be essential components of any workable solution.

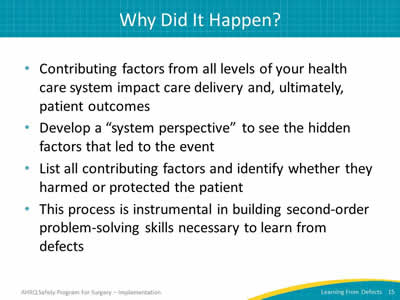

Slide 15: Why Did It Happen?

Say:

Then, move on to why the defect happened. With the timeline and process map created, consider the contributing factors from each level of your health care system, and how each impacts care delivery and patient outcomes. Develop a systems perspective, backing away from the accuse-and-blame approach. Isolate how the providers were in the position to make a mistake, rather than approaching the defect from a who-did-what angle.

Use the Learning From Defects tool to create a list of all contributing factors. List them; write them down. It may seem time consuming, redundant, or unnecessary, but it is extraordinary how many contributing factors you can identify through this process.

Using the team’s list of contributing factors, rate each factor.

Ask:

Were these contributing factors that led to or exacerbated the harm?

Or were there contributing factors that actually prevented the harm from being far worse?

Say:

Dig deep. Find what is hiding just below the surface, those protections that prevent the patient harm from getting out of control. Later, when you discuss interventions to ameliorate harm, those protections may need to be formalized to improve patient safety.

By digging into these contributing factors, your team is taking the first instrumental step before switching from first-order problem solving to second-order problem solving. Only then can you improve your long-term patient safety culture.

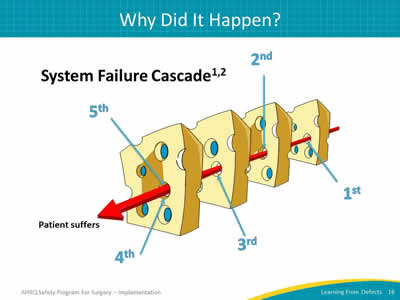

Slide 16: Why Did It Happen?

Say:

Each slice of Swiss cheese has a few holes. Normally, when you line up several slices of cheese, the random holes are not aligned. That is the way our systems are designed to work.

We have layers of protection throughout our health care system. While no system is perfect, we build redundancies into the care delivery system to compensate for minor defects and prevent catastrophe. Strong systems in health care are designed so that defects do not harm the patient.

However, occasionally the holes align. It only takes a few seemingly unrelated defects at different layers in the system to cause patient harm. The Learning From Defects process identifies the holes and the reasons they happened. It aims to also identify what actions will plug those holes, reengineer the system to catch holes before they line up, and end system gaps that lead to a patient injury.

Ask:

Can you give an example of a patient harm?

Can you list four or five defects at different stages in the care delivery that contribute to that patient harm?

Say:

In the case of an elderly woman falling down in her hospital room, let’s list some factors that might lead to a system failure cascade.

- She doesn’t tell her husband how frequently she gets dizzy.

- Due to the busy emergency room, the triage nurse does not notice that her cane was left behind.

- Two nurses can’t make it into work due to inclement weather, leaving the floor short-staffed.

- The patient is not assessed for fall risk, and no preventive measures are taken.

- The patient tries to get to the bathroom during the night and falls.

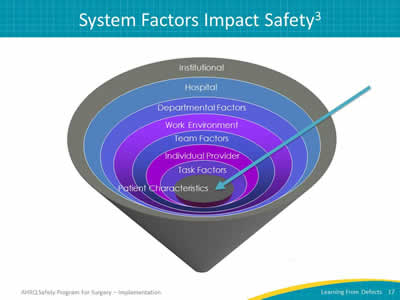

Slide 17: System Factors Impact Safety

Say:

Each level of the health care delivery system matters. Your institution, hospital factors, departmental factors, work environment, and team factors all contribute to your health care delivery system and impact patient safety.

Ask:

Who is on the team?

How does the team work together?

What’s the education or training of individual providers?

Does every team member know what is needed to perform the tasks?

Say:

Task factors also need to be considered. If a task requires two people, two trained people should be assigned to complete the task.

Finally, individual patient characteristics can and do contribute to system failures. Look across this entire spectrum and ask questions. Patient harms often have defect(s) at each of these layers.

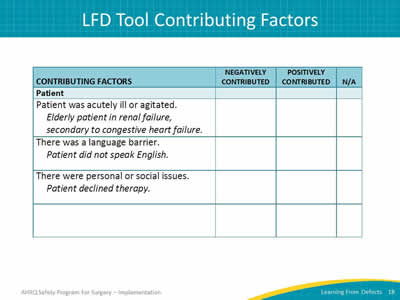

Slide 18: LFD Tool Contributing Factors

Say:

Document the institutional, hospital, task-level, and patient contributors to the situation with the Learning From Defects tool.

Ask:

Did the factor increase the harm or the risk for harm or decrease it?

Say:

Keep track of these key factors.

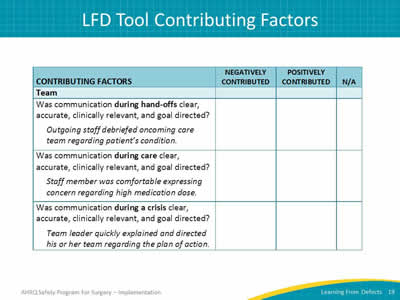

Slide 19: LFD Tool Contributing Factors

Say:

For example, what team factors contributed to or minimized or prevented harm? Document these observations in the Learning from Defects tool.

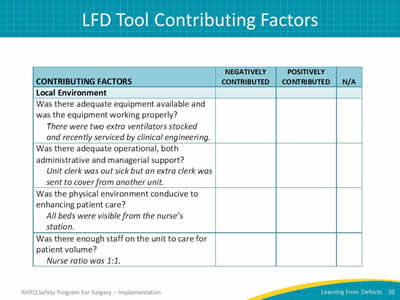

Slide 20: LFD Tool Contributing Factors

Say:

Do the same with factors in your local environment.

Ask:

What factors in your environment could contribute to a patient safety issue?

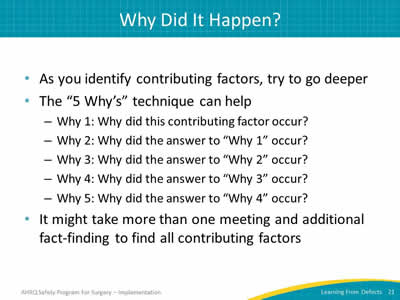

Slide 21: Why Did It Happen?

Ask:

Why did the defect occur?

Why did the contributing factor occur?

What led to the next factor that contributed to the defect occurring?

Say:

Try to understand the relationship among factors to determine an intervention. Identifying all of the contributing factors may take time. These analyses may require the surgical quality team to engage in several meetings or fact-finding activities to identify the contributing factors and understand why the defect happened.

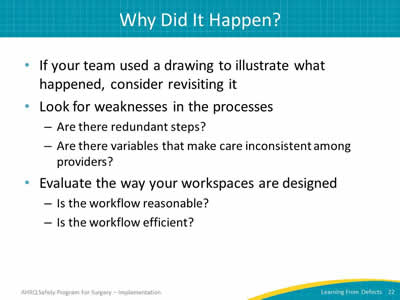

Slide 22: Why Did It Happen?

Say:

Make the whys visual. Revisit the process map, if your team created one. Map out what happened and include the whys under each defect. Use colored labels, sticky notes, or markers; make it visual. It is remarkable how much clearer an issue becomes when the entire team can see it at one time. People make the connections more easily; the system consistencies and inconsistencies suddenly make sense.

Look for weaknesses in the process.

Ask:

Do you have a redundancy or not?

What variables made the care inconsistent?

Say:

Identify as many elements as possible. Leverage the wisdom of your diverse team to share those different perspectives.

Evaluate how the workspace and workflow is designed. Discuss how those pieces relate to the care process.

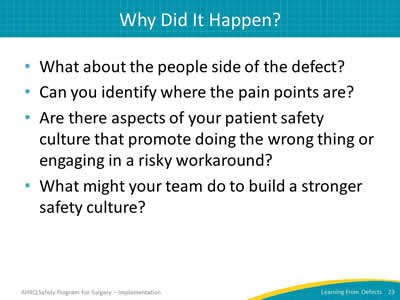

Slide 23: Why Did It Happen?

Say:

Think about the culture.

Ask:

Was there something about the safety culture, the operating room culture, or the PACU culture that led to that particular decision?

Are there aspects of the patient safety culture that promote doing the wrong things?

Does the hospital reward first-order problem-solving instead of second-order problem-solving?

Is there a process that tends to engage people in risky workarounds or risky behaviors?

Say:

These culturally rewarded behaviors can help or hinder the building of a strong patient safety culture. Recognizing the defects hindering true patient safety is the first step to building a strong safety culture.

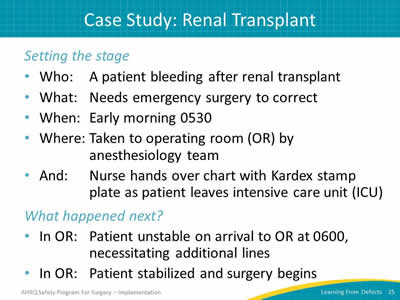

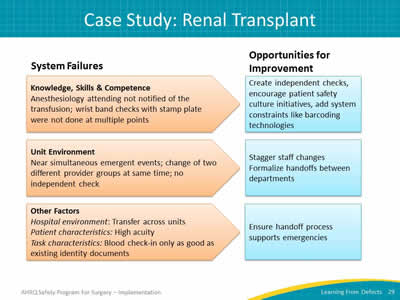

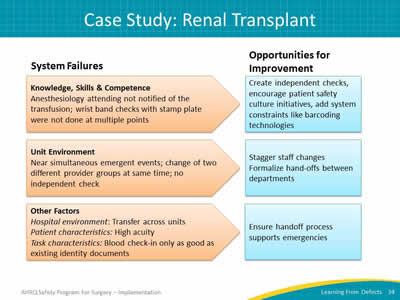

Slide 24: Case Study: Renal Transplant

Say:

Let’s consider a case study of a renal transplant patient.

Slide 25: Case Study: Renal Transplant

Say:

Around 5:30 a.m. an intensive care unit or ICU patient was bleeding internally after a renal transplant and needed emergency surgery.

The patient was taken from the ICU to the operating room or the OR by the anesthesiology team. On the way out of the ICU, the nurse handed over the chart with the Kardex stamp plate. Upon arrival at the OR, it was clear that the patient’s condition had deteriorated quickly. Once in the operating room about 6 a.m., the patient’s condition necessitated additional lines and resuscitation to get the patient stable for the operation. The patient was stabilized and the surgery to control the bleeding began.

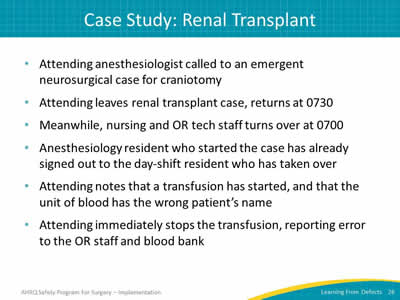

Slide 26: Case Study: Renal Transplant

Say:

Then the attending anesthesiologist got called away to start an emergent neurosurgical case for a craniotomy. Because the craniotomy patient was unstable, almost an hour passed before the neurosurgical case was underway. Once the craniotomy patient stabilized, the attending anesthesiologist returned to the renal transplant case around 7:30 a.m.

Meanwhile, the nursing and the operating technician staff, as well as the anesthesiology resident staff, turned over at 7 a.m. Thus, a new care team entered the renal transplant patient’s room at 7 a.m. The new anesthesiology resident received the signout from the previous resident and had begun a blood transfusion.

At 7:30 a.m. when the attending anesthesiologist returned to the operating room, he noticed the half-empty bag of blood being transfused. The attending anesthesiologist then read the wrong patient’s name on the blood transfusion bag. The renal transplant patient received a blood transfusion meant for another patient. The attending anesthesiologist immediately stopped the transfusion, reported the error to everyone in the operating room, and called the blood bank.

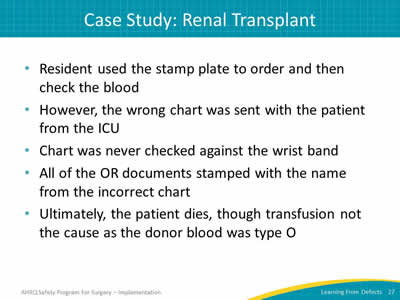

Slide 27: Case Study: Renal Transplant

Say:

The attending anesthesiologist asked about the wrong blood bag. The second-shift resident, who had taken over at 7 a.m., stamped the plate to order the blood and then used it to check the blood. However, no one noticed that the Kardex stamp did not match the patient.

It was later determined that the wrong stamp had left the ICU with the patient at 5:30 a.m. The stamp was for another patient, and the name had not been checked against the renal transplant patient’s wristband. Not only was the ordered blood incorrect, but every document in the operating room had been stamped with the incorrect patient’s name as well.

The patient died, although not due to the transfusion. The blood donor was type O, so there was no transfusion reaction with the recipient. Unfortunately, there were multiple other complications. Incompatible blood types could have led to an egregious patient harm.

Ask:

What factors contributed to this event?

Slide 28: Case Study: Renal Transplant

Say:

Look at the system. In the renal transplant case, contributing factors fell into the knowledge, skills, and competency areas.

The anesthesiology attending was not notified that the blood transfusion had started.

The wristband check failed at multiple points along the process.

There were near-simultaneous emergent events.

Two different provider groups were changing at the same time; there were no independent checks.

The patient needed to be transferred across units. One unit assumed that the other one had sent the correct information; no one double-checked.

No timeouts or debriefings occurred.

Note:

Spend 10 to 15 minutes discussing the case. Have participants explain what happened and why it happened. Through the course of discussion, additional details emerged.

Say:

This case happened many years ago, before timeouts were a part of the operating room protocols. The patient was transferred from a 16-bed ICU where the patients are well known. This particular patient had been in the ICU for several weeks with several operations. In fact, he was also the relative of one of the ICU nurses. It did not occur to anyone that this patient could be misidentified. The familiarity made the care team sloppy.

In addition, a parallel example from the airline industry helps to illustrate the importance of safety protocols in emergent situations. In the early 1990s in North Carolina, a plane was landing during a thunderstorm with wind shears and squalls.

The pilots missed the first approach and had to circle around again. Because of the squall line and emergency situation, they didn’t run their normal landing process. They hit another downdraft and shoved the thrusters forward to 110 percent. But they had never readjusted the flaps; they were in the down position. Instead of climbing, the plane plunged into the ground and killed everyone on board.

No matter how emergent a situation, violating safety processes can lead to disastrous consequences. It’s tough when the pressure is high and the patient is at risk. Interventions have to be simple and resilient.

Say:

This case highlighted many opportunities for improvement, like establishing independent checks in the system. A handoff that worked in normal situations failed in an emergent one.

Slide 29: Case Study: Renal Transplant

Say:

The confidence that the previous team had done the right thing without the redundancy and without double-checking the patient’s identity became a contributing factor.

Let’s stress that we presume that people are doing the best job they can, and we develop interventions that act as cognitive tools to help people do their job well. The problem occurs when we recoil from cognitive tools, like checklists, because we ARE good at our jobs. We are smart, dedicated people. We’re nurses. We’re doctors. We’re highly educated, and sometimes feel insulted by the tools. “Why do I need a checklist? I know my job.”

This point is key. You are bright, but you are still fallible. You are human and not a machine. Creating redundancies and checklists and interventions provide necessary and important tools to help us do our job better. That is different than a crutch to do our job as if we can’t do our job well, but essential tools to help us consistently do it better. It is sometimes hard for people to wrap their quite capable heads around that idea. Some of the interventions to prevent this error from happening again include fixing the holes in the Swiss cheese system.

When evaluating the defect as a system issue, we find many systems failures in the knowledge, skills, and competence arena. The anesthesiology attending was not notified that the blood transfusion was starting.

In the process of learning from defects, the team also identified issues with wristbands. The wristband should have been checked at multiple points in the care process. Near-simultaneous emergent events and changing provider groups led to the scenario where two people could not independently verify the information. Patient characteristics, the high-acuity situation, absolutely contributed to this defect. Task characteristics, likes the blood check-in, are only as good as the existing identity documents.

While today most hospitals utilize barcoding technologies, they were not present during this case. Barcodes alone would not prevent this defect; barcodes can be mismatched just like the Kardex stamp was in this case.

Many opportunities for improvement were identified, like creating and using independent checks, improving our patient safety culture, and creating system constraints.

Formal handoffs, timeouts, and debriefings prevent these errors; these processes must support emergency situations as well. Because emergencies strain any system. Your communication processes should be familiar and functional under normal conditions, but also work under the most possible stressful conditions.

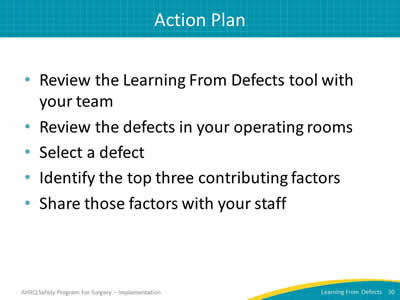

Slide 30: Action Plan

Say:

Review the Learning From Defects tool with your safety team. After reviewing the defects in your operating rooms from SSA responses or other sources, prioritize and select a defect to address. Identify the top contributing factors. Share those factors beyond your safety team with the entire frontline staff.

Slide 31: Learning from Defects Through Sensemaking II

Note:

This is an ideal place to pause instruction. Learning From Defects is a powerful tool and teams may benefit from processing the content over an extended period of time.

If you elect to pause instruction, it is recommended that you reintroduce the previous renal transplant case and use it as an example to address the third and fourth components of the LFD tool:

- How will you reduce it happening again?

- How will you know the risk is reduced?

Slide 32: Learning Objectives

Say:

Below are the learning objectives for this module:

- Use the Learning From Defects tool to perform second-order problem-solving.

- Create an action plan to address prioritized contributing factors.

- Evaluate the effectiveness of your intervention by measuring baseline and post-intervention performance.

- Present your finds to surgical department leadership.

Slide 33: Learning From Defects

Say:

As discussed in part one of this module, the Learning From Defects through Sensemaking process involves four major steps. Part one discussed the first two steps: understanding what happened by considering the viewpoint of the persons involved in the process that led to the defect; and understanding the reasons for the defect (the why). The focus is on the system, not on the individuals. The goal is to tease out systemic factors that contribute to errors and improve upon those factors.

This module focuses on the next two questions:

- How will you reduce the defect from happening again? What interventions will prevent the defect from happening again? Focus on second-order problem solving, even with defects that have not led to patient harm.

- How will you know the risk is reduced? Establish metrics that will identify reduction of the defect. These data points can inform staff and patients, as well other stakeholders, about your patient safety efforts, including achievements as well as additional opportunities for improvement.

Slide 34: Case Study: Renal Transplant

Note:

Duplicate of Slide 29.

Say:

In the case study, why did the defect occur?

The new resident did not notify the attending anesthesiologist about starting the blood transfusion.

There were no mechanisms in place to check the wristband against the Kardex stamp plates. These checks were neither performed in the ICU before the patient left it, nor were they performed in the OR before the surgery began. No redundant systems were in place in this emergent situation to ensure that the documentation matched the patient.

The unit environment contributed with near-simultaneous emergent events: the renal transplant patient as well as the craniotomy patient. There were two different groups of providers due to the shift change. There were no independent checks and no proper sign outs between the different providers about the patient. The attending anesthesiologist was not present for the decision to transfuse. Multiple care areas (ICU and OR) along with multiple care teams required clear communication, yet it was unclear if proper handoffs occurred. Patient characteristics also contributed as both patients were of high acuities.

Task characteristics also contributed to the defect. The blood check-in was only as good as the existing identification documents. The resident checked the patient’s identity against the Kardex plate, but not the wristband. Shift changes among staff were not staggered, resulting in a mass change in providers independent of the case status.

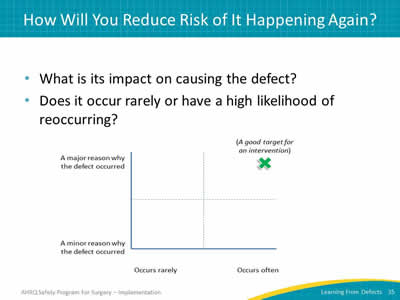

Slide 35: How Will You Reduce Risk of it Happening Again?

Say:

When learning from defects, select each contributing factor to assess its impact on causing the defect.

Ask:

Does the factor occur rarely and does it have a high likelihood of happening again?

Say:

Prioritize the defects to tackle. Focus on a defect that carries the greatest risk of harm to patients, is most likely to occur, and has a likelihood of intervention. Select the “low-hanging fruit” —something that is relevant and fixable; something that can generate team momentum.

After selecting a defect, prioritize the contributing factors. Each defect has many contributing factors, making it difficult to immediately address each one. So, prioritize the contributing factors as follows:

- Was the contributing factor major or minor?

- What is the frequency of the contributing factor?

The ideal target for developing an intervention is a factor that is a major contributor to the defect and occurs frequently. These should be the top priorities for improving patient care.

Your surgical quality team will need to balance the scope of the intervention effort. If there is something that occurs rarely but has a singular impact on this particular defect, consider working on a factor that falls in the left upper box in the grid. If the factor is a minor contributor to the defect, but occurs often, then consider intervening on this factor. As a general rule, consider factors that occur often or are major reasons for the defect—the low-hanging fruit. That’s where you’ll get the big impact. All contributing factors will need to be addressed, so use this prioritization grid to help your team develop an achievable action plan.

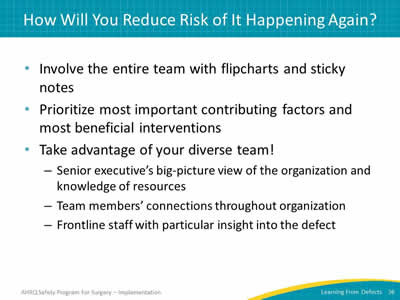

Slide 36: How Will You Reduce Risk of it Happening Again?

Ask:

How will you create your interventions?

How will you address that particular defect?

Say:

Brainstorm possible interventions. With your surgical quality team, document all ideas for intervention. Don’t evaluate or criticize an idea. Use a flip chart, a chalkboard, or a whiteboard, or tape oversized paper to the wall.

Note:

This is a great opportunity to involve entire staff rather than just the surgical quality improvement team. Consider posting opportunities to brainstorm in areas that all staff members frequent.

Say:

Review interventions likely to have the biggest impact and evaluate potential barriers to implementation.

Ask:

What is the fiscal cost for each intervention?

Say:

If an intervention has potential and a low number of barriers, is relatively inexpensive, and fits into the current workflow, encourage your surgical quality team to prioritize that intervention.

Target contributing factors that have interventions that are easy to implement, and that will generate team momentum. For each intervention, evaluate the difficulty to implement it and the expected impact.

Lean on your interdisciplinary team. The senior executive can offer organizational vision and inform about interventions that the organization can or cannot support. Keep an open mind. Encourage colleagues to become involved.

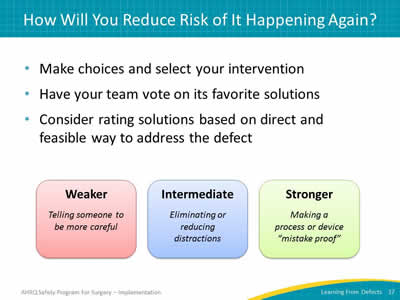

Slide 37: How Will You Reduce Risk of it Happening Again?

Say:

After brainstorming and then prioritizing the list of targeted interventions, make choices and select your intervention.

Have your team vote on the solutions it favors.

Try using the dot voting method. Post the compiled list of possible interventions. Include an envelope of multicolored dot stickers and instructions that each staff member take a few dot stickers and place one next to each intervention they like. They can place all three votes on a single idea or spread them out. Make voting available to cover multiple days and shifts.

Then, rate the solutions based on frequency and expected impact. It may be helpful to determine if the targeted intervention is first-order or second-order problem solving. Strive to implement interventions that will have an intermediate or strong impact.

Be mindful of the strength of interventions. Telling someone to be more careful is weaker than eliminating competing distractions or mistake-proofing a process.

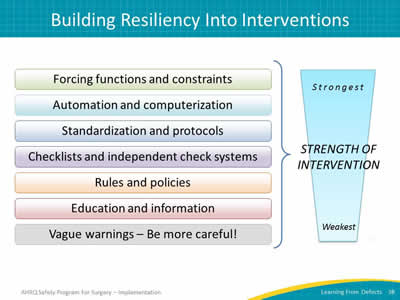

Slide 38: Building Resiliency Into Interventions

Say:

Build resiliency into the intervention. When evaluating an intervention, consider its impact and strength. Warning individuals to do a better job or be more vigilant about safety is a relatively weak intervention. Humans are fallible and cannot be vigilant all of the time. Asking people to perform better will not help them perform their job better if the workplace conditions are still error prone.

Education is important, but on its own is also a weak intervention. Education can make people aware of the problem, but it alone will not eliminate mistakes.

Rules and policies are stronger interventions. But, not everyone will read or remember the policies. After all, there are many policies.

Creating checklists and implementing independent check systems are stronger than the ones mentioned thus far. For example, implement a mandatory second check on a patient identification badge before the patient leaves the ICU.

Create standardization and protocol. Automate systems. Force functions. For instance, if you want to mandate a followup antibiotic after specific procedures, place the order automatically or require an overwrite justification. Implement constraints that prevent mistakes. These are the strongest types of interventions.

Ask:

What interventions have you tried?

What were the strengths of these interventions?

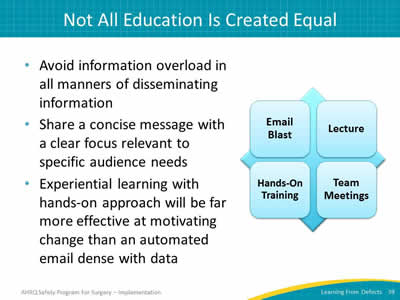

Slide 39: Not All Education Is Created Equal

Say:

Part of the reason education alone is a weak intervention is because not all methods for educating are effective. Depending on the defect, some educational strategies are better than others.

Email blasts are not effective for teaching how to do a job better or to make sure patients are safer. Lectures may be more effective, given the face-to-face nature of that session. Team meetings allow members to share their educational experience. There is interaction between the learners and between the learner and the teacher. This type of education is stronger than emails and one-way lectures.

Studies have shown that hands-on training events are effective, because the real engagement helps imprint the information being taught. Asking people to read, learn, and apply the learning enables people to form memories of the process. This is a very strong educational method.

When doing an educational intervention, strive for concise, clear, and relevant messages. Also, consider how to make it resilient and strong.

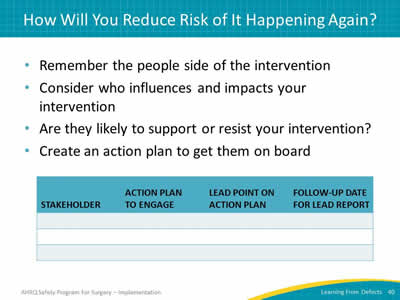

Slide 40: How Will You Reduce Risk of it Happening Again?

Say:

Remember the people side of the intervention. Reconsider the renal transplant case study and the system of stamps or barcoding.

Barcoding is a great technology, but what happens if the patient is barcoded incorrectly—that is, the barcode number assigned to a patient is really that for another patient? That barcode error may carry all the way through the process of care. A barcoding process to prevent blood transfusion is only as good as the operator using that system.

System automation can help people do their job better and improve consistency of care. Ensure that the new intervention blends into the current workflow so that it can serve its purpose: preventing harm to patients.

Consider all stakeholders who influence and impact the intervention.

Ask:

Will there be resistance to the intervention?

Will it make the jobs of the operators easier or harder?

What education on the system is required?

Say:

Do not ignore the resisters. As difficult as they may seem, they usually offer kernels of truth. Take time to present plans and solicit their feedback; they may surprise you and make the intervention far stronger and achievable. Try to turn an intervention resister into an ally.

Create an action plan to get buy-in to the intervention.

Ask:

Who are the stakeholders?

Who needs to be part of a successful decisionmaking process?

Slide 41: How Will You Reduce Risk of it Happening Again?

Say:

It’s hard to get people engaged. It’s hard to get people involved in the process you want them to be involved in. People are busy. Lean on your surgical quality improvement team to overcome those real barriers and solve problems. Your interdisciplinary team can identify methods for engaging their colleagues.

Inform all interested parties about the details of the intervention. Ensure there is thorough understanding with no ambiguity regarding the intervention. If people walk away and aren’t sure about the expectations, the intervention will fail.

Ask:

Is the intervention being carried out consistently?

Say:

For example, imagine your team implements a new process to reduce a serious system defect. Training was conducted over a weeklong period during the day shift. Three weeks after implementation, data show that the intervention is only used 40 percent of the time. In addition to the relative lack of awareness with the night shift, the day shift has not achieved consistent implementation either. Identify the reasons behind the inconsistency and perhaps schedule a training event more conducive to all staff members.

Create workflow changes and process changes to ensure consistent implementation of the intervention.

Slide 42: How Will You Reduce Risk of it Happening Again?

Ask:

How will you know the risks were reduced?

How will you know your interventions worked?

Are they being implemented consistently and as intended?

Do your staff members, including your stakeholders, know about the intervention?

Say:

When examining whether the defects were reduced, remember to ask the frontline staff and stakeholders. While subjective evaluations can provide valuable qualitative information, focus on data-driven quantitative metrics for evidence that the risk of the defect reoccurring has been reduced.

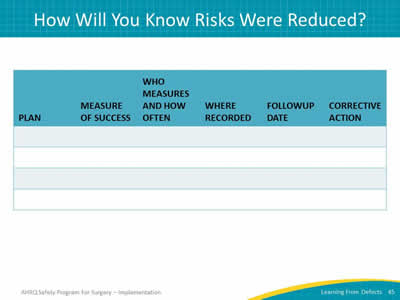

Slide 43: How Will You Know Risks Were Reduced?

Say:

Plan how you will measure success. In the case of reducing central line-associated bloodstream infections or catheter-associated urinary tract infections, measure the outcome rates of these events.

Ask:

Did they decline or increase?

Say:

However, interventions to reduce wrong-site surgeries may take years of collecting data before it is clear whether the intervention is effective. Frankly, wrong-site surgeries are too important a defect to merely hope for success. Other interventions may not take as long.

Develop an audit plan to track measures that will identify whether the risks for defects have been reduced. For example, if you want to measure how often patients maintain normothermia to prevent surgical-site infection, audit 30 patients once a month. Track the progress of the intervention month by month to determine progress. In the first month, you learn that only 15 out of 30 patients had the proper body temperature. Then, you tweak the intervention and audit again. Be prepared that much iteration may be necessary to achieve consistency.

Implement an audit plan so you don’t drown in data collection. Select a sample of cases to follow over time. Collect baseline data to see if the intervention is reducing or increasing the risk for defect.

After completing audits, share the data with your surgical quality improvement team and your senior executives. Also, provide feedback to your frontline staff. Post the data to bulletin boards. Share the data publicly. Keep your staff engaged; let all stakeholders know their efforts are working.

Review the Learning from Defects process. If you are not achieving the results you want, start again. Review the original defect. Review what happened, why it happened, and what interventions were put in place. Review the brainstorming notes. Follow these steps to identify if the intervention reduced the risk for defect. Identify any new information and secondary defects introduced by the new intervention. This is an iterative process.

Slide 44: How Will You Know Risks Were Reduced?

Say:

Identify and document your measure of success. Include baseline data and post-intervention data in your intervention evaluation plan. Outline your data collection and audit plans: the frequency of the collection or the audit and the sample size.

Audits and evaluations require feedback to be impactful and meaningful. Share your findings with the surgical department leadership as well as your frontline providers.

Slide 45: How Will You Know Risks Were Reduced?

Say:

Celebrate and share improvements with your frontline staff.

Ask:

How is the next patient going to be harmed?

What can I do to prevent that harm?

Say:

Analyze a defect once every quarter or every month, depending on what your team can do. When you’ve resolved a defect, begin working on another. Capitalize on one success and the resulting team momentum. This continuous effort to reduce risk for patient harm improves your unit’s culture of safety. When providers see improvement, gain a voice, and see their concerns about patient harm ignite change, they remain engaged and eager to make more improvements.

Slide 46: Ongoing Key Questions

Say:

Make the Staff Safety Assessment available all the time. Place it in a folder and tack it to the bulletin board or provide a box in a central location. Encourage staff to complete the survey anytime they see a safety problem. Make it an ongoing process by asking staff to complete this assessment frequently. Build it into your workflow. It engages your frontline staff and changes the culture of safety.

Ask:

Have you asked your frontline staff the two questions of the Staff Safety Assessment?

How often do you ask your staff?

How often do you review the responses?

The PSSA (Perioperative Staff Safety Assessment) features two questions:

- How is the next patient going to get an SSI?

- What can I do to prevent that SSI?

Use either the SSA or the PSSA depending on the goals of your surgical quality improvement team.

Slide 47: Action Plan

Say:

- Review the Learning from Defects tool with your team.

- Prioritize all defects, and then select a defect to address.

- Select at least one defect per month to begin resolving.

- Consider using the surgical morbidity and mortality conferences as a venue for sharing your stories.

- Show your staff that you’ve reduced the risks for patient harm.

- Provide evidence of improvements for your entire staff and senior leadership. Thank them for their efforts.

- Share these efforts and results. Share stories of reduced risk or the positive impact to patients.

Slide 48: References

Slide 49: Additional References