Optimize Briefings and Debriefings: Facilitator Notes

AHRQ Safety Program for Surgery

Slide 1: Optimize Briefings and Debriefings

Say:

This module is the first of two parts discussing briefings and debriefings. Teamwork and culture improvement are a big part of this project. Evidence supports that addressing cultural issues in conjunction with the technical work improves infection rates. Both safety culture and technical interventions must be managed to sustain progress.

Briefings and debriefings provide strong tools for managing some of that change. Even interventions with an abundance of evidence can prove difficult to implement. This work is not an easy checklist. Here we will address the many aspects of briefings and debriefings: the fundamentals, the lessons learned by many organizations and from the literature, what works and successful implementation strategies. The goal is not to add yet another required piece of paper, but to develop a meaningful process that benefits the entire care team and our patients.

This module will review the evidence and lessons learned, and will provide tips for maximizing the briefing and debriefing process. Also, a hospital team will share its story about implementing and then optimizing briefings and debriefings, as well as share its successes.

Slide 2: Learning Objectives

Say:

First, let’s describe the characteristics of effective briefings and debriefings, along with what matters about these processes. Implementing the briefing and debriefing process will require evidence to garner surgeon and other stakeholder buy-in. We will present the evidence base for briefings and debriefings for you to share with the surgical staff.

Each hospital is likely in different stages of briefings. Some may have implemented briefings; some have not.

Ask:

Have you implemented a briefing process that did not go so well?

Say:

Others are in more mature stages and can offer strong lessons in how to achieve success with briefings and debriefings.

The critical component of earning stakeholder buy-in and turning debriefings into a meaningful process comes after the debriefing meeting has ended. Teams must prioritize and investigate defects identified during operating room debriefings. Debriefings are an opportunity to uncover both latent and actual errors to reduce risk over time, make your work more efficient, and improve patient safety. They are an opportunity to LISTEN to the wisdom of your frontline providers as defects occur.

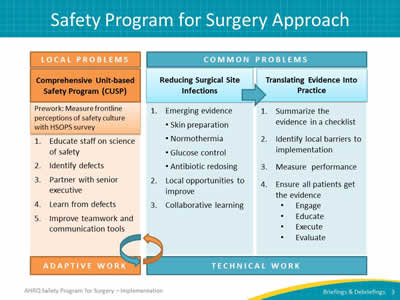

Slide 3: Safety Program for Surgery Approach

Say:

This safety program has a strong technical component. We summarize the evidence around what therapies work and what therapies have efficacy for our patients, and then we must respond with locally useful guidance.

Ask:

How do we take the evidence and turn it into something that care providers can use?

How do we augment our work processes to include the emerging evidence?

Say:

In addition, the adaptive work is addressed with the Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program (CUSP) involving the management of culture. Similar to the systematic management of technical work, CUSP provides tools for managing the safety culture in our environment, including the science of safety, a process for identifying and learning from defects, and the relationship with your senior executive. It also includes improving teamwork and communication.

Slide 4: Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program

Say:

The best places in a surgical setting to improve that teamwork and communication are in the briefing and debriefing phases of a surgical case. We will share a few tools to support briefing and debriefing. Many tools are available. The key is to develop a tool that works for your surgical arena and fits your work process.

Slide 5: Basics of Briefing and Debriefing

Say:

Let’s take a few moments to discuss the basics of briefing and debriefing.

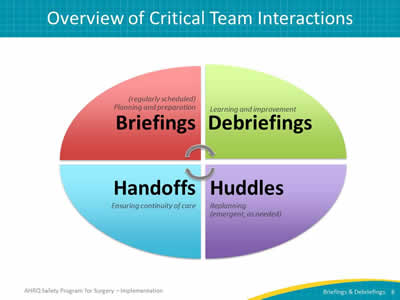

Slide 6: Overview of Critical Team Interactions

Say:

First, we will clarify some language. Even with a goal of clear communication, we often use the same terms for different things, or different terms for the same things. So for the sake of our discussion, this is how we will refer to critical team interactions.

The four primary types of critical team interactions in surgery are briefings, debriefings, huddles, and handoffs. Briefings are regularly scheduled meetings designed to plan and prepare for the procedure. By default, they occur at the beginning of a case to ensure every member of the care team is on the same page.

Ask:

Does everyone understand and agree on the plan and the equipment required?

Is the team anticipating potential complications and preparing contingency plans?

Say:

This powerful process improves both the recognition of issues and response time.

Debriefings are often brief meetings immediately following a case, either regularly occurring or under specific or novel circumstances. They provide an opportunity for the team to learn and for the system of care to improve over time. Debriefings also allow teams to identify issues that need to be addressed for future cases, like equipment issues or a breakdown in communication. By reflecting on how well teams work together, the team can then articulate successes and failures. Group discussion makes the successful interactions more likely to continue and allows less successful behaviors the chance for elimination.

Huddles occur on an emergent or as-needed basis. If something unexpected happens during a case, the plan may no longer suit the circumstances. The huddle pulls together the care team for replanning purposes.

Handoffs ensure continuity of care when the patient transfers to different clinical areas or to different providers.

Slide 7: What Is a Briefing?

Say:

As discussed, a briefing is a discussion between two or more people, often the surgical team, using succinct information pertinent to a case.

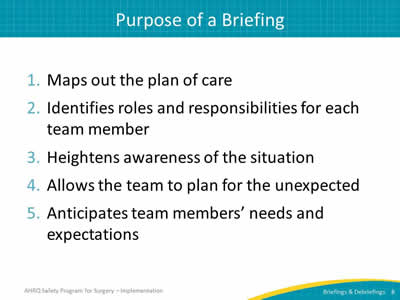

Slide 8: Purpose of a Briefing

Say:

The purpose is to map out a plan of care. Another goal is to identify roles and clarify responsibilities for each team member. Briefings heighten awareness of the situation and allow the surgical team to plan for the unexpected. It allows a forum that anticipates team members’ needs and expectations for the case.

Ask:

So what are the specifics of this patient?

Where could things go wrong with this procedure and specifically with this case?

If something goes wrong, what should we look for and what are we going to do if that happens?

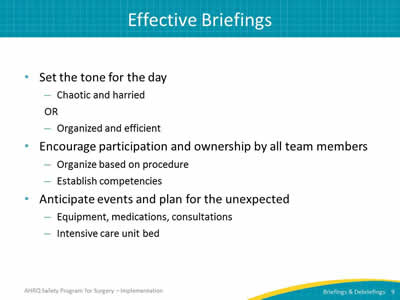

Slide 9: Effective Briefings

Say:

Effective briefings set the tone for the day.

Ask:

Will the case be chaotic and harried or will it be organized and efficient?

Say:

Take a few minutes, or even a brief 30 seconds, to go through the plan. Clarify roles and responsibilities. The briefing process organizes the case and makes both the care and the day more efficient. Evidence supports the upfront investment of time, which pays dividends in efficiency of turnover time and case time. The case goes more smoothly and the team can better react to obstacles.

Encourage participation and ownership by every team member. In health care and other industries, people struggle with speaking up when they have a concern or are uncomfortable with the plan. We’d like to think it is not a problem, but frequently staff members are not encouraged to contribute. By setting the standard of expecting 100 percent participation, your surgical team gains a powerful tool.

Often surgical teams work with different or even unfamiliar providers for each case. Take the opportunity to introduce each team member, explain skill competencies, and assign tasks. Understand who is on the team, what their background is, what their expertise level is, where they might need assistance, and where they will contribute. This essential communication does not take much time and drastically improves communication.

When a team anticipates events and plans for the unexpected, they are better equipped to meet both the team’s and the patient’s needs.

Ask:

Do we have the equipment and medication on hand if a complication arises?

Is an intensive care bed available?

Slide 10: Briefing Checklist

Say:

You will find typical things on a briefing checklist, and many examples are available. You may need to customize a checklist to fit the needs of your surgical area. Who is on the team? Do we have those roles? Do you understand your assigned role? Do we have a plan of care? In the event of a long case, what staff availability issues, breaks, or turnover issues are present? Any potential workload or resource issues, like equipment and supplies, or anything that could impact the case, should be discussed in the briefing.

Slide 11: Team Debrief

Say:

To recap, a debriefing provides an opportunity to reflect, learn, and drive continuous improvement. It can cover communication and interactions immediately after the case.

Ask:

How well did we interact together?

Did you not have the information you needed?

Were you working under a plan that was not consistent with what I thought the plan was?

Say:

Debriefing can and should also cover topics that need more attention to address. We will share examples of equipment issues and malfunctions, or other defects that require a system correction. Take the opportunity to log any findings, discuss the problems, and direct the issue to where it can be resolved.

A strong feedback loop is absolutely critical for debriefing to achieve results. Debriefing alone can be an immensely powerful tool to raise awareness of provider concerns and engage providers in safety improvement work. Rather than expecting staff to complete yet another task with the information falling into a black hole, follow up on issues identified from debriefing. As defects are addressed, share this feedback with all providers.

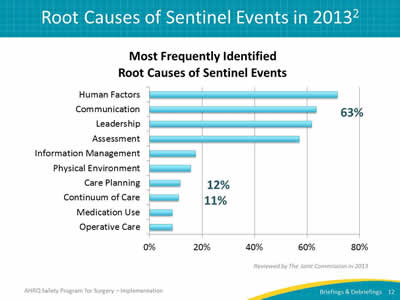

Slide 12: Root Causes of Sentinel Events in 2013

Say:

Communication failures across the health care system contribute to more than 60 percent of sentinel events. The Joint Commission defines a sentinel event as an unexpected occurrence involving death or serious physical or psychological injury, or the risk thereof. Serious injury specifically includes loss of limb or function.

Ask:

What can we do to improve communication among our surgical teams?

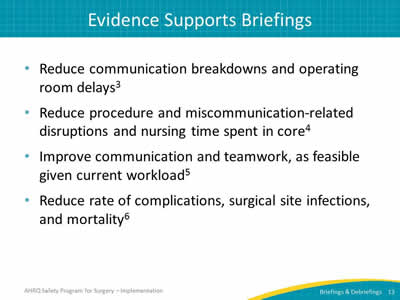

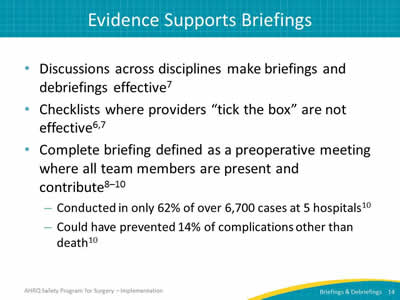

Slide 13: Evidence Supports Briefings

Say:

Many studies link briefings and debriefings in the surgical services to key outcomes. There are no large, multiple-site randomized controlled trials that have examined preoperative briefings or postoperative debriefings to date. However, there have been several multisite studies that found preoperative briefings to be effective when done as intended, rather than perfunctory ticking off the boxes.

You can reduce the number of communication breakdowns. You can reduce operating room delays. Reduce procedure and miscommunication-related disruptions. Reduce traffic in the operating theater. Briefings and debriefings can improve communication and teamwork; reduce complications like surgical site infections (SSI), and reduce mortality rates.

Slide 14: Evidence Supports Briefings

Note:

See Russ et al., 2013, for a review of existing literature. See Haynes et al, 2011, and Mayer et al., the 2015 study of the WHO surgery checklist in eight hospitals in eight different countries and followup rebuttal to arguments highlighting mixed results found in other smaller studies.

Say:

Existing evidence demonstrates that it is the discussion, particularly across disciplines, that makes briefings and debriefings effective. Just the act of ticking off the box on a briefing checklist is not effective.

A complete briefing is defined as a preoperative meeting where all team members are present and contribute to the discussion. A study of 6,714 surgical admissions across 5 academic and community hospitals suggested that complete briefings were conducted in only 62 percent of surgical cases. Results suggested that 14 percent of complications other than death could have been prevented with complete briefings.

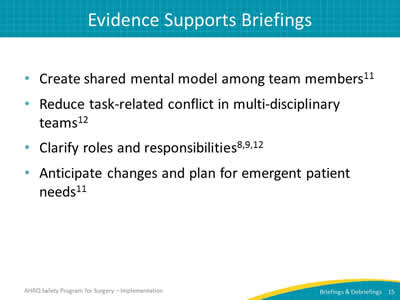

Slide 15: Evidence Supports Briefings

Ask:

Why are briefings effective?

Say:

Briefings provide a critical mechanism for creating a shared mental model among team members. This is particularly critical for reducing task-related conflict in multidisciplinary teams. The surgical setting involves functionally diverse teams, where people do different tasks based on specialized knowledge and must work together to coordinate their efforts. These differences increase the probability that team members may see or perceive the team’s needs, goals, or priorities differently, leading to conflict or unclear expectations. Briefings can help clarify roles and responsibilities, as well as how they might change or be adapted in an emergency.

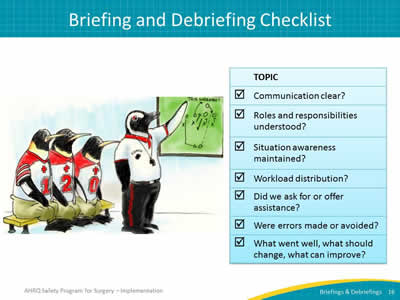

Slide 16: Briefing and Debriefing Checklist

Say:

A debriefing checklist addresses how the team works together.

Ask:

Was our communication clear?

Were our roles and responsibilities clear?

Were we able to maintain a common situation awareness of what was happening?

Did we do a good job of managing the workload and switching people in and out for long cases?

What went well, what should we change, and what can we improve next time?

Slide 17: Why Briefings and Debriefings?

Say:

Fundamentally, these goals are quite basic. We know teams perform better when they have a plan, when that plan is shared and coordinated, when all involved understand the approach, and last, when they are overcoming obstacles that obstruct that plan.

Ask:

Is this because many briefings and debriefings have devolved into mere checklists?

Say:

Checklists can be great tools and consistent reminders of how to walk through a process. But checking the boxes does not equate to mindful engagement, as the evidence clearly demonstrates.

Slide 18: Why Briefings and Debriefings?

Say:

When the World Health Organization published its surgical safety checklist a number of years ago, the use of briefing and debriefing checklists was associated with large reductions in mortality. That checklist is included on Slide 29. Later studies failed to see that effect, including a followup on that initial WHO study. The evidence showed that 50 percent of the decrease in mortality was associated with the facility’s preexisting safety culture, rather than the checklist. So, if an organization enjoyed a good safety culture, implementing these tools yielded significant benefit. But an organization with a relatively poor safety culture saw minimal improvement from the checklist tools.

And that is because of mindfulness. When people value these tools and their teammates, they pay attention to them as they use new tools, with significant results. If staff members do not feel valued and simply check off a box, it becomes an administrative task without strong benefits. Building mindfulness and improving the overall safety culture is the tough but necessary part of any intervention.

Slide 19: How Do You Create a Mindful Process?

Say:

Two ways to build a mindful process include coaching and briefing. Coaching involves role modeling and feedback. It’s having leaders who recognize the value of effective communication and model that behavior for peers. These leaders and champions are respected in the organization and show by example that the organization values this behavior. As discussed earlier, evidence shows that active executive partnerships sustain improvement efforts.

Second, the briefing and debriefing process closes the loop with outcomes. Nothing is more demotivating to frontline staff than repeatedly dealing with the same issues.

Ask:

Can you imagine the frustration of debriefing after each case and it sounds like a broken record? The same issues resurface in case after case, but nothing changes.

Will they continue to debrief on those issues?

Why would anyone waste time?

Say:

That debriefing process is going to fade over time if nothing changes. Debriefing identifies system defects in a way that allows and encourages correction. It validates the process and encourages a consistent delivery of care.

Ask:

How are you going to leverage debriefing and achieve meaningful results?

How are you going to track those defects, follow up, and advise staff on the resolution?

Say:

It is an investment, but it is critical to value frontline staff, resolve barriers to system issues, and ultimately improve patient care.

Slide 20: Operating Room Briefings and Debriefings

Slide 21: Timeout: The Universal Protocol

Say:

Timeout is one form of a briefing that challenges teams. Often, the timeout has become an administrative function. We know this because wrong-sided surgeries would never happen if timeouts were more effective. But that’s not the case. But timeouts provide a hard stop at a critical time to confirm the care team on the right page with this patient.

Slide 22: Briefings: Expanding the Timeout

Say:

Briefings are an expansion of the timeout with more flexibility. Different sections can occur at different times. In fact, that flexibility is paramount to success—making sure the briefing protocols fit the workflow of your cases, your day, and how your team works together.

In many briefing and debriefing processes, one particular flaw has been noted repeatedly–timing. If a protocol requests information at the wrong point in time, it interrupts the case rather than supporting team communication and execution of tasks. It is not helpful to question patient positioning at the point of incision. A briefing protocol must reflect the process your frontline providers have established for each surgical area.

Successful briefings allow all team members to introduce themselves, particularly in clinical settings that frequently include new faces on the surgical team. Write down the assigned roles on a white board and give team members an opportunity to share relevant skills. Encourage full participation and questions, including how to facilitate a timeout.

The surgeon should share the goal of the operation. Each care team member should have the opportunity to identify issues or ask questions.

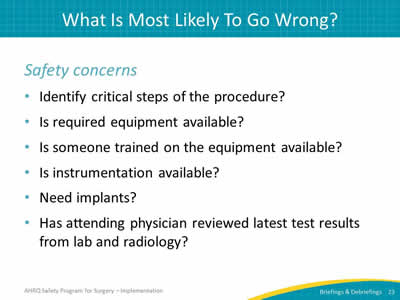

Slide 23: What Is Most Likely To Go Wrong?

Ask:

What is most likely to go wrong?

Where are the critical steps of this procedure?

What equipment do we need to have available?

Do we have the right expertise available to use that equipment, any instrumentation, implants, et cetera?

Has the attending physician reviewed the latest x-ray and lab results?

Say:

Discuss these safety concerns. These are types of questions frontline providers need to know before every case.

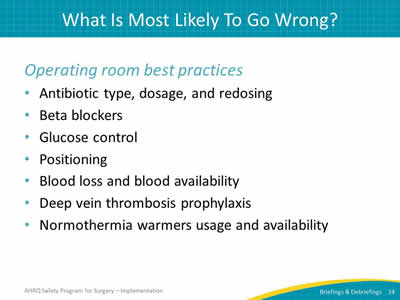

Slide 24: What Is Most Likely To Go Wrong?

Say:

Include your surgical site infection intervention bundle on your briefing checklist. This provides an opportunity for the surgical team to process each item before the case starts.

Ask:

Do we have enough of the right type of antibiotics on hand?

Say:

Cover beta blockers, glucose control, positioning (at the right point in time), blood loss and blood availability, deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis, patient warming, et cetera. It does not take much time for the surgical team to run through relevant items.

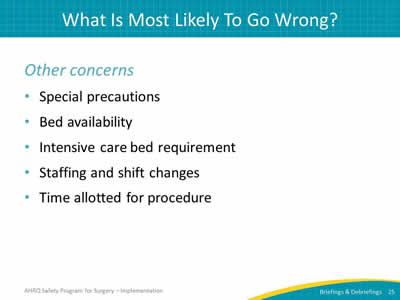

Slide 25: What Is Most Likely To Go Wrong?

Say:

Include other concerns that may complicate the case, such as special precautions, bed availability, any special requirements for the patient setting after the surgery, staffing, et cetera.

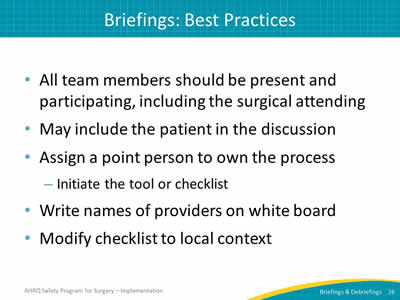

Slide 26: Briefings: Best Practices

Say:

It may seem oversimplified, but it is absolutely fundamental to have every member of the surgical team present and participating in the briefing process. In observations of hundreds of briefings, there was variability in who was actually present. In addition, we have also found significant variability in who engaged actively in the discussion.

Often the circulating nurse leads the protocol, while the rest of the team either listens passively or is distracted with other tasks. While many hospitals may label that exchange a briefing, it does not improve team communication, efficiency, or likely even patient care.

Ask:

How do you get everyone attending and participating in the briefing?

Say:

Assign a point person to own the process and initiate the tool or checklist. Develop a structure that allows everyone to share information. White boards make a visual and visible statement in the clinical environment, one that has been well received in several hospitals. Write the names of providers on the white board; this will reinforce team members’ ability to recall names, assess skill level, recognize roles and acknowledge assigned tasks.

Start with either your existing protocol or one from another organization, but tools must be tailored to fit your clinical area and work processes. Engage frontline providers through your CUSP team to design the checklist and process that mirrors your local context. They should pilot and revise any tool based on feedback from the frontline staff using the tool.

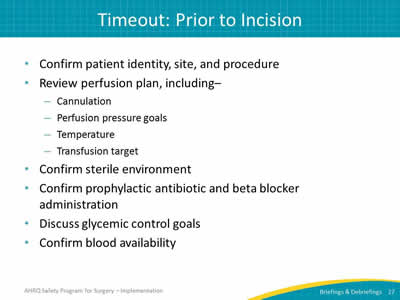

Slide 27: Timeout: Prior to Incision

Say:

A timeout can occur just before incision to verify the patient identity, surgical site, and procedure. Review the perfusion plan, including cannulation, perfusion pressure goals, temperature, and transfusion target. Ensure the operating room is sterile and that prophylactic antibiotics and beta blocker plans are communicated and can be administered. Discuss the glycemic control goals and confirm the blood availability. Again, you will need to adjust the content for your timeouts to include all relevant information for your surgical setting.

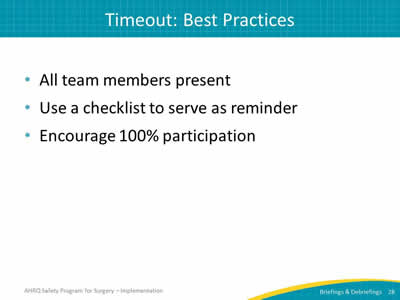

Slide 28: Timeout: Best Practices

Say:

Successful briefings and timeouts require the presence and attention of all team members. Briefings and timeouts should follow a checklist valued by the frontline providers using it. This improves the flow of information and the expectation of team members, and allows any uncertainties to be addressed proactively.

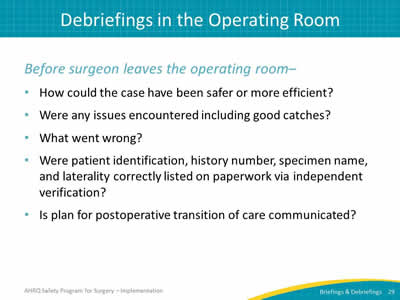

Slide 29: Debriefings in the Operating Room

Say:

Structure debriefings so that they happen before the surgical attending leaves the operating room. As much of the team as possible should be present. That can prove a logistical challenge as staff may leave at different times. Finding the appropriate time to perform a short debriefing can be a challenge, but can be achieved.

Ask:

What could have made the case safer?

Were there any issues encountered?

Any good catches?

What went wrong, if anything?

Were patient identification and specimen name verified?

Is the plan for postoperative transition of care communicated?

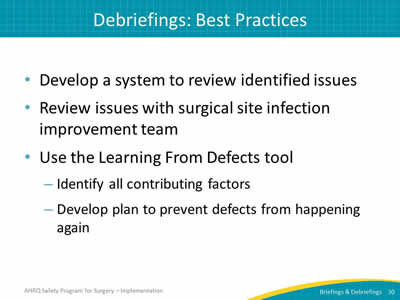

Slide 30: Debriefings: Best Practices

Say:

Debriefing comments present tremendous opportunities for patient safety improvement. Develop a system to review the issues or defects identified during the debriefing process. System defects cannot likely be corrected at the end of each case, but those comments are the challenges your frontline staff face on a regular basis. Review those defects with your CUSP team or a surgical site infection quality improvement team. The team can prioritize the issues and start addressing them. Some of them will be very easy fixes; some will not.

Use the Learning From Defects tool. It provides a strong structure to work through the problem and identify all contributing factors. With input from all stakeholders, you can develop a sustainable solution that meets the needs of the frontline staff and the patients.

Slide 31: Real-Time Identification of Defects

Say:

To reiterate, customize every communication tool based on the needs in your surgical unit. Surgeons often lead the surgical care team and the formal conversations about each case. Initiate candid discussions with surgeons about effective strategies for briefing and debriefing. Share your expectations for the briefing and debriefing process in terms the surgeon can relate to. For instance, tell the surgeon how you will support their needs by addressing issues that plague their cases. Then show them.

The power of debriefings grows after the debrief ends. You will find a real-time identification of defects and real-time system of learning. Allocate protected time for a nurse to address the defects. Even a small amount of time, as little as 4 hours a month, can make a difference visible to the surgical staff. Keep a record of defects with a tracking mechanism of progress or actions taken. Share the log and progress at staff meetings. This feedback will show your staff that your organization value staff input and is willing to invest resources to alleviate staff concerns.

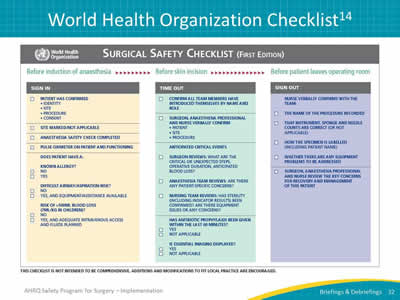

Slide 32: World Health Organization Checklist

Say:

You may be familiar with the surgical safety checklist developed by the World Health Organization. If you do not already have a briefing checklist, it may provide a starting point for developing one that fits your surgical area.

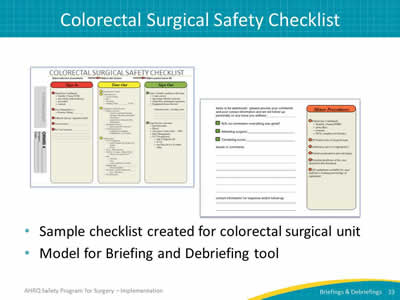

Slide 33: Colorectal Surgical Safety Checklist

Say:

Here is a briefing tool developed by the colorectal CUSP team for Johns Hopkins Hospital. It is more streamlined, designed specifically for its patient and case needs.

The debriefing tool is very simple, featuring a few lines to record anything that needs to be addressed for future cases. The perioperative or circulating nurse often completes this form, but your team can decide on the appropriate role on your unit.

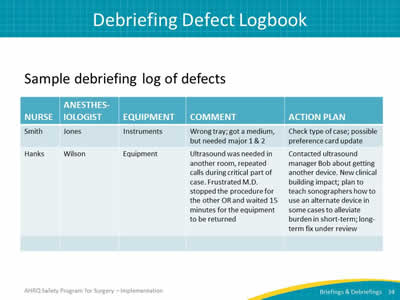

Slide 34: Debriefing Defect Logbook

Say:

This logbook example was first shared in the Implementing Your SSI Bundle module. It includes the type of issue, the stakeholders, details about the defect, and the action plan. Very simple in nature, it provides a mechanism to log defects and track progress. Share with your staff the issues identified last month or last quarter, the issues resolved, and any issues in progress and the status.

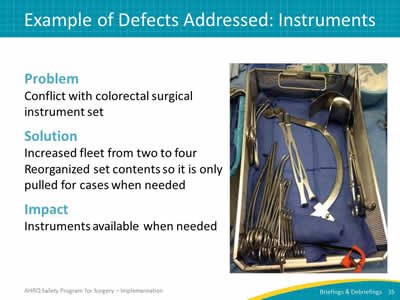

Slide 35: Examples of Defects Addressed: Instruments

Say:

You may recall this example from the Implement Your SSI Bundle module. The colorectal team identified a shortage of instrument sets numerous times through the debriefing process. Based on the recorded evidence, the team was able to advocate for expanding the fleet. Without the documented track record of multiple cases impacted by missing equipment, the hospital had not prioritized the request for additional resources.

Slide 36: Case Study: Laparoscopic Surgery Trays

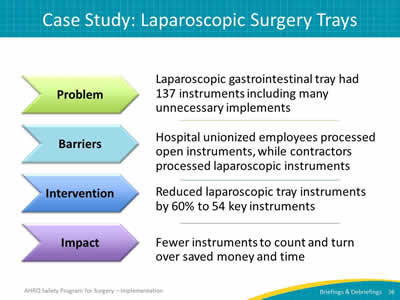

Say:

Debriefing also uncovered an inefficiency related to instrument sets. The original laparoscopic gastrointestinal sets had almost twice as many instruments, requiring long counts of many instruments routinely not used on cases.

Slide 37: Case Study: Laparoscopic Surgery Trays

Say:

Debriefing at the end of a case, the staff questioned why the sets included so many instruments that were not used. That comment was addressed through the CUSP team, and the trays were updated to reflect current needs.

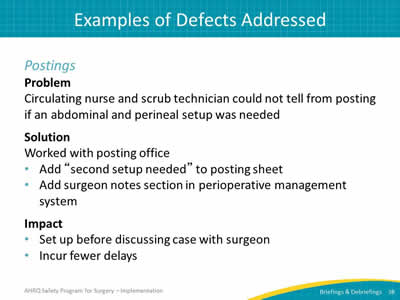

Slide 38: Examples of Defects Addressed

Say:

This example stems from confusion around how cases were posted. Nursing staff had difficulty recognizing when different sets were needed for abdominal versus perineal cases. The equipment issues and subsequent delays were captured and recorded in the debriefing process. The CUSP team worked to change how the cases were posted. The new posting language, shown here, provides much clearer instructions about the equipment required for the upcoming case. Preparation for the case could begin before briefing with the surgeon with fewer errors and delays.

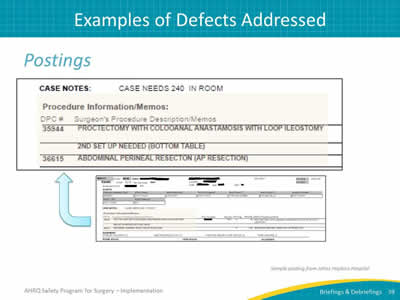

Slide 39: Examples of Defects Addressed

Say:

The new posting language, shown here, provides much clearer instructions regarding the equipment required for the upcoming case.

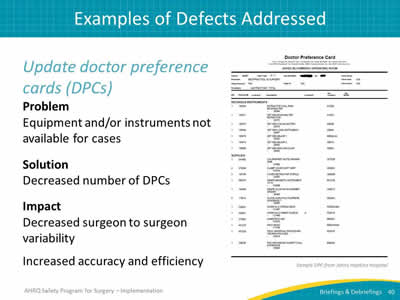

Slide 40: Examples of Defects Addressed

Say:

This is a strong example because preference cards cause headaches in hospitals all over the country. Preference cards specify surgeons’ preferred instruments for each procedure, but are often out of date or incomplete. In addition, the cards increase the inconsistencies between individual surgeons. By tackling the preference cards, the safety program team decreased the overall number of preference cards, removed inaccuracies, reduced waste, and drastically reduced variability among surgeons. Because the team included a respected surgeon champion, the team was able to respect the individual provider needs while also improving consistency. These changes resulted in quantifiable improvements in number of errors, inefficiencies, and counting time. Recall from the science of safety the first step—standardize care. The surgeons appreciated having the correct equipment available on time and the surgical team was better prepared for their cases.

Slide 41: What Can We Catch?

Ask:

What harm can you avoid?

What can we catch with briefings and debriefings?

Do we have the right consent?

Do we have the right patient?

Are we prepared with the right equipment, implants, instruments, and those types of things?

Have any specimens been labeled correctly?

Say:

Raise the care team awareness of each patient’s needs, such as comorbidities, specimens, and documentation. Ultimately, patient care can be improved through effective briefings and debriefings.

Slide 42: What Can We Accomplish?

Say:

The goal is to build a shared mental model among your team—the same idea about who is on the team, what the plan is, how to work together, what the patient needs.

Teams can reduce missing equipment and reduce hazards.

Ask:

Did you know that more than 70 percent of sentinel events involve human factors, such as team disruptions and unnecessary distractions?

Slide 43: Adapting to Local Context

Say:

Over time, effective briefings also improve safety culture. They intersect the technical work of preventing SSIs with the adaptive work of teamwork and communication.

The interventions must be relevant and meaningful to your frontline providers. Avoid an irrelevant checklist that looks more like an outdated administrative task. Engage the people who will use the tool to customize it for their clinical area. Use the two-question survey, the Perioperative Staff Safety Assessment, for staff input. The surgical audit tools will also identify system flaws.

Fixing local defects is a powerful and visible strategy to gain staff buy-in and encourage participation.

Slide 44: Lessons Learned

Say:

Reshaping safety culture takes time, commitment, energy, and focus. Briefing and debriefing provide powerful tools for real improvement in communication and teamwork.

It flattens the organizational hierarchy and places the focus firmly on the patient. It shares the wisdom of every role. By adapting to the local context, the process becomes meaningful to your frontline providers. Identify and address defects proactively to improve work processes and improve patient care.

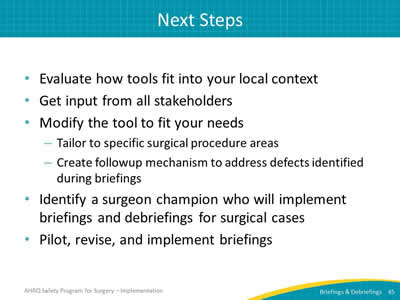

Slide 45: Next Steps

Say:

Evaluate how these tools fit your local context. Recognize that every hospital team is likely in different stages with briefings and debriefings.

Ask:

Are there opportunities to revamp your process?

Say:

Start by getting input from stakeholders. Ask what works and what does not work or what is missing. Tailor the tools to fit your intervention bundle and surgical area. Develop a process to follow up on the comments, or defects, uncovered during the debriefing process.

Identify a surgeon champion to pilot the new and improved briefing process. Observe the process and solicit feedback. It may take a few iterations to develop a process that works well. Be prepared to test, revise, and continually improve.

Slide 46: References

Slide 47: References

Slide 48: References

Slide 49: Hospital Team Experience: Briefings and Debriefings

Say:

Here is a brief overview of one surgical team’s experience implementing the briefing and debriefing process.

I will share some background information on this hospital for your reference. It has 10 operating rooms and averages about 800 cases a month. It covers all procedures except for transplants.

Three hospitals in the network have adopted this safety program process as well.

Slide 50: Briefings and Debriefings

Say:

The surgical teams employ preoperative procedure verification, briefing, and timeout with a whiteboard before the start of each case.

Slide 51: Barriers to Debriefing

Say:

This process started 3 years ago. At the hospital, it was handed down from the administration and was not initially well received. I am sure you can relate to yet another paper form. Hospital staff questioned whether it was going to work; what did they want staff to do? It’s been a journey. After the initial hesitation, the team was surprised with the success. That is one of the reasons the team wanted to share it.

Slide 52: Success With Debriefing

Say:

It took having physician champions and surgeons onboard that made the implementation happen. As mentioned earlier, the system in place to document these issues is the first part. You definitely have to share it and follow up on the issues.

It was not easy, but the staff saw the team following up on issues. Morale went up, and it even helped with management. Before this process, staff were constantly interrupted with nonurgent issues. Now, providers document on the debriefing form and are confident that it will be followed up. So I’ll share with you how that followup is done.

Slide 53: Tips for Successful Debriefing

Say:

Three things made the new process successful and continue to drive progress.

First, it needs to be a system that is easy to use. Previously, each operating room had a glitch book. It proved a difficult system: the book had to be located to record an issue; then it had to be collected, reviewed, and returned. The system wasn’t used much.

Instead, the checklist is placed in each chart for every case, so it is consistently available when it is needed. It is turned in at the end of the case. The checklist does not remain with the chart, but stays in the department.

Second, develop a system to review issues. Nothing will kill a new process faster than never reading what the frontline providers took the time to record. Review the comments with operating room management, frontline staff, and surgeons. After issues are identified, assign followup actions to correct system flaws.

Third, be transparent. Keep a log of all defects and prioritize which defects will be addressed and when. Record the steps taken to address defects and share the resolution of defects. Provide updates on progress on more difficult issues that require more time to correct.

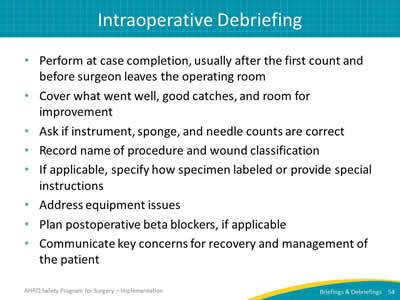

Slide 54: Intraoperative Debriefing

Say:

The team goes through the debriefing process near the end of the case. At first, the surgeons challenged the new process. They were concerned that they were expected to stop during the case and handle paperwork. We assured them that the surgery would continue, but the nurse would debrief to confirm the procedure, how to label the specimen, what went well, and any need for improvement.

The team also covers equipment issues and communicates postoperative plans. The debriefing form gets turned in for every case, whether or not there was something to write. Also, staff confirm that each checklist is returned.

The operating room nurses appreciated the debriefing. At the end of the case, the nurse performs the handoff in recovery. Verifying the procedure name and specimen labeling became routine for the cases, so the handoffs went smoother and all doubt was alleviated. Specimens could be handled and labeled properly while the patient and the surgical team were still in the room. Previously, mistakes might be uncovered after the case’s conclusion when the team had dispersed.

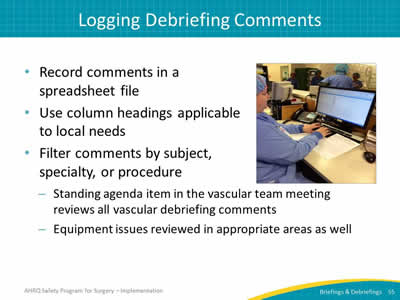

Slide 55: Logging Debriefing Comments

Say:

A clerical staff member is assigned to input each debriefing comments on a daily basis. Our log is a spreadsheet that breaks the comments into categories. Then the appropriate comments are reviewed in the staff meeting for that group. For instance, any comments collected regarding the vascular surgical team are filtered and shared with that team.

The surgeons actually like the process. They can process the comments for the entire surgical area with all team members present. They are not involved in a case or with a patient. They became very invested in reviewing the comments and making improvements. Addressing those debriefing comments made their job easier.

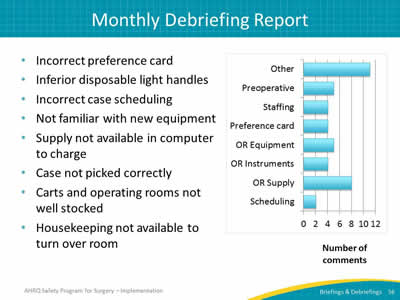

Slide 56: Monthly Debriefing Report

Say:

A breakdown of the debriefing comments is posted each month. One issue pertained to disposable light handles. When the new equipment was piloted, it was OK. But once they were in the packs, the quality was poor. Multiple complaints about the light handles raised the priority, and the product was changed.

If staff mentioned they were not familiar with new equipment, a quick in-service training was scheduled. It was a concise way to share with the entire team the types of issues that were trending in their operating rooms.