Implementing Your Surgical Site Infection Prevention Bundle: Facilitator Notes

AHRQ Safety Program for Surgery

Slide 1: Implementing Your SSI Prevention Bundle

Say:

This module is about implementing your surgical site infection (SSI) prevention bundle.

Slide 2: Learning Objectives

Say:

This module will help you develop an implementation plan for your SSI prevention bundle.

You will learn to identify and address local barriers to implementing your SSI prevention bundle with the Barrier Identification and Mitigation tool.

Ask:

Do you have an SSI prevention bundle?

Slide 3: SSI Bundle Characteristics

Say:

Intervention bundles were developed in the mid-1990s to improve the care of mechanically ventilated patients. These bundles collected evidence-based practices, typically five to seven elements because social psychologists say we can remember about five to seven things. Once that list gets longer, we have a hard time remembering the items. Think of seven-digit phone numbers—same reasoning.

Bundles have promise. If needed, bundles could expand over seven items. However, a shorter list can focus your effort and help communicate the concept within the organization.

Bundles are dynamic and can evolve over time. They should represent local wisdom and local defects—what’s going on in one hospital will differ from what is happening in another.

The development of the Surgical Care Improvement Program (SCIP) measures represents an effort in which surgical experts identified salient interventions to prevent SSIs. But nationally, improving compliance with SCIP measures has not translated into reductions in SSIs. The evidence does not currently support an association between performance in SCIP measures and successful reduction of SSIs. Vary the content of the bundle based on your local defects. Standardize the approach used to develop a bundle, not necessarily the elements in a bundle.

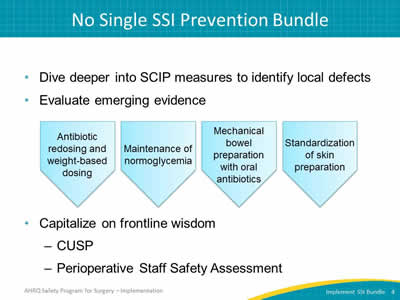

Slide 4: No Single SSI Prevention Bundle

Say:

Dig deeper into what the SCIP measures represent within your organization to make sure patients receive evidence-based therapies. Consider the guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Consider the revised “Compendium of Strategies to Prevent Healthcare-Associated Infections in Acute Care Hospitals,” published in 2014 by the Society for Hospital Epidemiologists for America (SHEA) and the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA). In the Compendium, it’s not just about the right antibiotic, the right timing, and the right choice, but it’s also about making sure that we have the right dose of antibiotic and the right redosing schedule for the antibiotic. These metrics go beyond the current SCIP measures.

One successful strategy is to talk to the frontline staff. Ask structured questions. Use the questions in the Staff Safety Assessment.

Ask:

How do you think the next patient will be harmed?

What do you think we can do to prevent it?

Say:

Tapping into the wisdom of the frontline staff is powerful on a number of levels. They know the ground truth within the organization. They know your patients.

Social science literature teaches that by asking staff what their concerns are and then acting to remedy the concerns, staff members feel that they have been heard and their opinions valued. This is an exceedingly powerful opportunity to engage your staff.

Build your SSI prevention bundle based on local defects. Dive deeper into the SCIP measures. Consider the potential application of emerging evidence within the organization. Talk to frontline staff to identify how they would reduce surgical site infections.

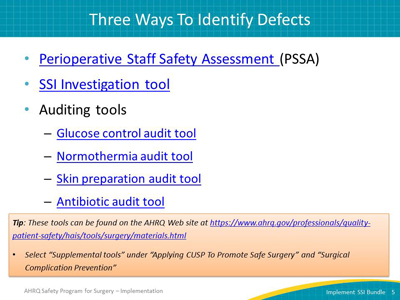

Slide 5: Three Ways to Identify Defects

Say:

Consider these three tools when identifying local defects:

Perioperative Staff Safety Assessment (Word, 1.57 MB)

CUSP employs the Staff Safety Assessment, often called the two-question survey. The Safety Program for Surgery has modified that tool for the surgical setting into the Perioperative Staff Safety Assessment.

Ask:

- How do you think the next patient will be harmed?

What do you think we can do to prevent it? - How do you think the next patient will develop a surgical site infection?

What do you think we can do to prevent that infection?

SSI Investigation Tool (Word, 1.8 MB)

This tool will identify lapses in infection prevention processes that may have contributed to SSIs and will identify inconsistencies in practice patterns. Investigate as many SSIs as possible, but there is no right number to review. Abstract this information from the patient’s chart and present it to the team.

Suppose your investigation reveals that only 50 percent (instead of 100 percent) of the patients received the appropriate redosing of antibiotics, or that 10 percent of the patients were hypothermic when they came out of the operating room. Share these data points with the senior leadership. Tell them, here are patients who have been harmed because they developed SSIs. Perhaps these SSIs were not preventable, but these patients did not receive the evidence-based therapies. We can do better. This powerful message and data are an opportunity to engage senior executives as well as the frontline staff.

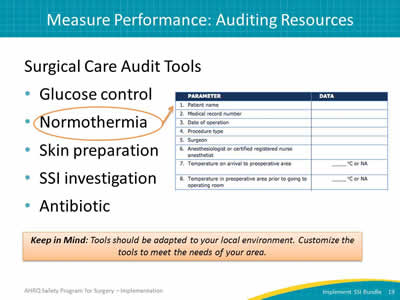

Auditing Tools

We talked about digging deeper into SCIP. Data collection is challenging, and it can prove impossible to build an auditing logic within existing electronic medical records. One strategy is to audit the next 10 patients. Aim for frontline staff to own this effort. They will work together but autonomously to identify opportunities to improve care when it comes to concerns such as glucose (Word, 1.67 MB), normothermia (Word, 1.59 MB), skin preparation (Word, 1.57 MB), or antibiotics (Word, 1.6 MB). Entice the staff: tell them that no matter the results, they will get to present at a meeting with leadership; they will share their work and insights. Financial incentives are not necessary. Tap into things that folks value: that feeling of doing something important, something meaningful, that voices are heard, and that they are appreciated for the work they do.

Slide 6: Translating Evidence Into Bedside Practice

Say:

Now we will discuss how to translate evidence into bedside practice.

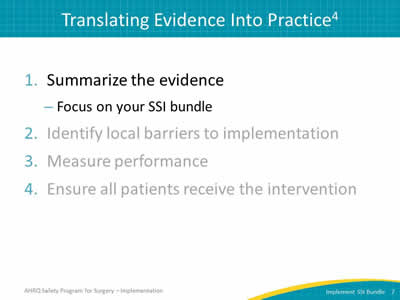

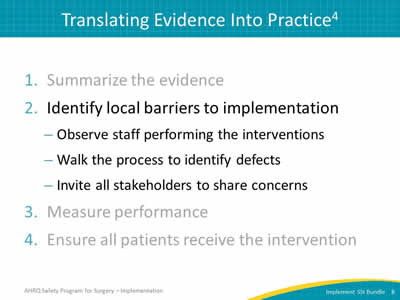

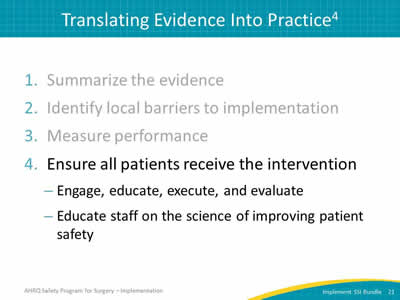

Slide 7: Translating Evidence Into Practice

Say:

Consider the information gathered.

Ask:

What are some local defects?

Say:

These can change over time but are based on the results of a local investigation: five or seven things to focus on. Consider next translating that bundle into practice. As an emerging area of science, this can be challenging.

Slide 8: Translating Evidence Into Practice

Say:

The model used in translating evidence into practice was first developed as part of a statewide intensive care unit program. It was used in the national central-line associated blood stream infection prevention program. It’s been used in a SSI reduction program. Called the Translating Evidence into Practice (TRiP) model, it asks: What is it that you want to focus on? What’s the evidence that is important to you? That’s the basis for the SSI prevention bundle: focus on the elements in the bundle, as those are the evidence-based practices that will need to be applied into practice.

Ask:

What are the local barriers to implementation?

Why aren’t patients normothermic?

Why aren’t patients receiving appropriate redosing of antibiotics?

Why aren’t patients receiving the therapies they should?

Successful strategies include watching frontline staff perform the interventions. Many hospitals have observers in the operating room. While this approach has pros and cons, it identifies opportunities for improvement.

Have the frontline staff walk the targeted process to identify defects. A walk-through encourages direct participation and observation and allows frontline staff to contribute their wisdom. Invite all stakeholders to observe or participate in the walk-through. Staff members may understand an issue differently after multidisciplinary aspects are shared.

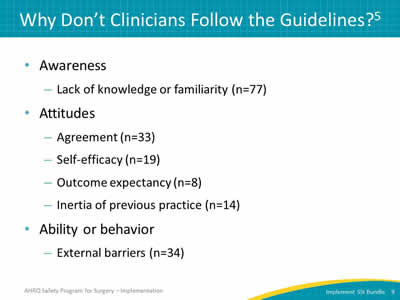

Slide 9: Why Don’t Clinicians Follow the Guidelines?

Say:

The driving force behind the TRiP methodology is the core belief that clinicians want to do the right thing. No care provider is intentionally ignoring evidence about antibiotics and surgical site infections. Yet an auditing of medical records shows that the correct dosage is not delivered; appropriate redosing does not happen.

Ask:

What gets in the way of consistent compliance with evidence-based practices?

Say:

One framework to use in understanding why clinicians don’t follow the guideline is the “Three As.”

Awareness

The first A is about awareness: providers are not aware of the evidence or protocol. For instance, a physician may not have read the literature for maintaining normothermia. Different preoperative skin preparation products have different procedures.

Ask:

Does the nurse know the correct way to use ChloraPrep®*?

Say:

It is not the same as using Betadine*. Many hospitals grant privileges to visiting surgeons, making it difficult to provide consistent education on emerging evidence. Providers may not know that national professional societies advocate for glucose control less than 180 milligrams per deciliter throughout the perioperative period.

Ask:

Do providers understand that antibiotic A needs to be redosed every 4 hours or that antibiotic B needs to be redosed every 6 hours?

Say:

Providers are expected to know a tremendous amount of information and emerging evidence.

Ask:

What do providers need to know?

Attitudes

The second A is attitudes or agreement. Depending on how the evidence is acquired or shared, providers may not agree that the given evidence applies to her or his patient.

Ask:

Did you share enough of the evidence to garner buy-in?

Did the new quality analyst send a six-page email detailing a new procedure without any opportunity for questions or feedback?

Does each provider know why a protocol has changed?

Do providers agree with this recommendation?

Say:

Providers need to know the rationale for the given practice. All new interventions must share why the change is required, you must share the evidence for buy-in.

Ability

The third A is for ability. Providers want to do the right thing, but it may be too hard to do the right thing.

Ask:

Are there too many steps? Is the procedure too time-consuming without reasonable return?

What are the barriers? If antibiotics redosing is required, is the medication readily available? Is the proper equipment available to maintain normothermia?

Say:

Clinicians can only comply with protocols when they have the resources and equipment to do so.

*Note: Use of brand names is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

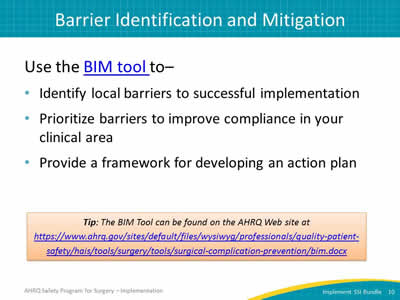

Slide 10: Barrier Identification and Mitigation

Ask:

How do you know if the clinicians can and will comply with your intervention?

Say:

The Barrier Identification and Mitigation (BIM) tool navigates the awareness, agreement, and ability barriers to better understand why every patient is not receiving the evidence-based therapy. The BIM tool helps to identify and prioritize barriers. It also provides a framework for developing an action plan for addressing barriers.

Tip: The BIM tool (Word, 1.73 MB) can be found on the AHRQ Web site.

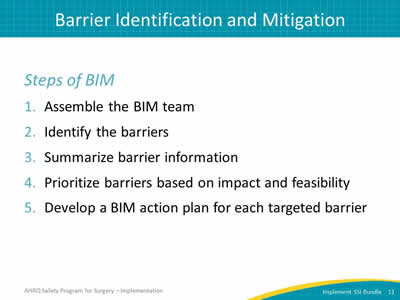

Slide 11: Barrier Identification and Mitigation

Say:

Assume a recent audit shows that only 16 percent of your surgical patients are receiving proper antibiotics redosing.

Ask:

Why isn’t each patient receiving the correct antibiotic, the correct dosage, and the correct redosage at the correct time (or therapy A, B, C, D, and E?)

Say:

First, consider assembling a BIM team, perhaps a subset of your surgical quality team.

Second, involve the frontline staff and recognize them for their contributions. Ask them about the obstacles that impede compliance with the intervention.

Ask:

Are they aware, in agreement, and/or able to comply?

Say:

Clinical settings provide complicated services that require a sometimes herculean effort from multiple disciplines and departments. Expect many barriers and find as many as possible.

Third, list the barrier uncovered from your work with all relevant providers and stakeholders.

Next, prioritize the barriers based on impact and feasibility.

Ask:

How often is a barrier expected to occur? Frequently or rarely?

Say:

Rate each barrier on how likely it is to impact compliance. Prioritize the most likely and the most severe barriers.

Last, develop a BIM action plan for each targeted barrier.

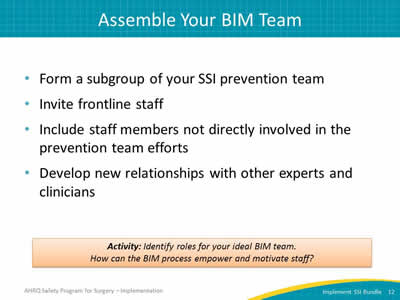

Slide 12: Assemble Your BIM Team

Say:

Step One—Form a subset of your CUSP or SSI prevention team. Include frontline staff members.

Forge new partnerships with other clinicians. Communicate with colleagues who are not on your surgical quality team, but who provide great care. Respected colleagues interested in quality and safety may provide valuable insight, particularly if they represent diverse disciplines. Often staff members are not aware of quality improvement efforts or how they can get involved.

Activity: Identify roles for your ideal BIM team. How can the BIM process empower and motivate staff?

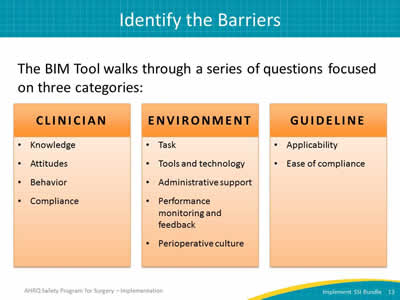

Slide 13: Identify the Barriers

Say:

Step Two—Using the BIM tool, walk through the potential barriers with stakeholders. The BIM tool covers a series of questions focused on three categories: clinician, environment, and guideline.

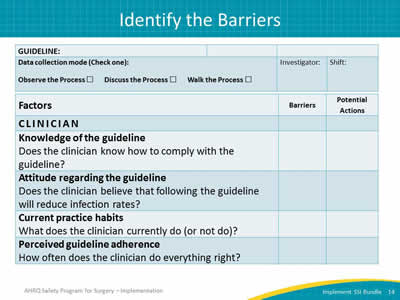

Slide 14: Identify the Barriers

Say:

Use this tool as a discussion guide with your group. Focus first on the potential barriers for clinicians.

Ask:

Do the clinicians know the guidelines and how to comply with them in the organization? (awareness)

Do the clinicians agree with the guidelines or are there concerns that need to be addressed? (agreement)

What does the clinician currently do or not do? (ability)

Do the clinicians think that they’re already doing a good job?

Say:

Be prepared to provide data that show the compliance with intervention, or how many patients are not receiving therapies A, B, and C.

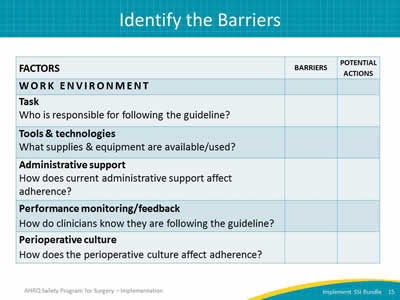

Slide 15: Identify the Barriers

Say:

Look at the work environment.

Ask:

Is it clear who’s responsible for providing therapy A, B, or C?

Are the necessary supplies and equipment available?

Say:

There may not be answers to all of these questions, and not all of these questions may apply to your environment. They will identify potential barriers. Once a barrier is identified, your team can begin to mitigate it.

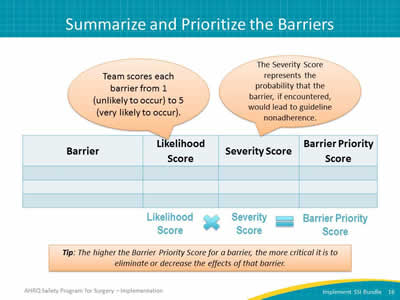

Slide 16: Summarize and Prioritize the Barriers

Say:

Step Three—After identifying the barriers, list them.

Step Four—Now prepare to prioritize them. Resources are limited, and addressing many things at once is not feasible. Determining which barriers are more important will also allow you to prioritize the team’s efforts.

As a group, assign a likelihood score for each barrier. One indicates a barrier is unlikely to occur; five indicates a barrier is very likely to occur.

Again as a group, assign a severity score that represents the probability that the barrier, if encountered, would lead to guideline nonadherence. One indicates a barrier with a lower probability of noncompliance; five indicates a barrier with a high probability of noncompliance.

For instance, if warming equipment is available, but down the hall, someone on the care team can retrieve the device. Your team would rate this barrier with a lower severity score than a barrier of broken warming equipment. If the devices are all damaged, it is highly unlikely that the care team can comply with the intervention.

To determine the barrier priority score, multiply the likelihood score and the severity score. Rank the barriers from high to low scores; tackle the high scores (16 and above) first, then address the low scores (15 and below).

Tip: The higher the barrier priority score, the more critical it is to eliminate or decrease the effects of that barrier.

Slide 17: Develop a BIM Action Plan

Say:

Step 5—Now focus on the plan of action.

Ask:

How will you know when progress is made on each effort?

Who will lead each effort?

When will there be followup on the action item?

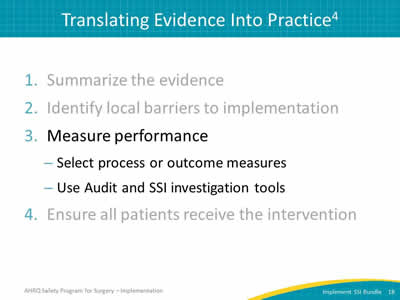

Slide 18: Translating Evidence Into Practice

Say:

Measure your performance. Your data become the evidence to motivate staff to change their practice. Dedicate time to collecting data and determine how well the appropriate therapies are provided.

A variety of process measures are available. Your data collection does not have to be sophisticated. For example, find the number of patients who come out of the operating room normothermic: YES for patients with a temperature greater than or equal to 36 degrees Celsius; NO for patients with a temperature less than 36 degrees Celsius. Consider the SSI rates for outcome measures.

Track performance over time. Use the SSI Investigation tool to determine progress in implementing your SSI prevention bundle with patients. Covered in detail in a later module, the audit tools help you measure compliance.

Slide 19: Measure Performance: Auditing Resources

Say:

Several audit tools are available to evaluate how well the implementation or intervention has changed practices.

Tip: Tools should be adapted to your environment. Customize the tools to meet the local needs of your clinical setting.

Slide 20: Practical Applications

Say:

A member of a SSI prevention team made the following statement during a coaching call.

Read:

“Identifying the contributing defects for patients who develop a surgical site infection is feasible. It unites staff members with a common goal, puts a face to the numbers, and most importantly, is EASY to do.”

—SSI prevention team member

Slide 21: Translating Evidence Into Practice

Say:

The last step of the TriP methodology is to ensure that all patients are receiving the evidence-based therapy. Use the 4 Es to lead change: engage, educate, execute, and evaluate. Also, educate staff on the science of improving patient safety.

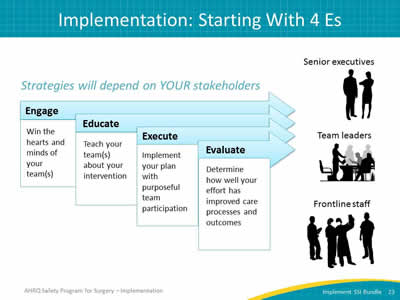

Slide 22: Leading Change with 4 Es

Slide 23: Implementation: Starting with 4 Es

Say:

Different people as well as different roles react to different strategies. Engaging a senior executive requires a different strategy than engaging a surgeon or a nursing colleague to participate.

The 2014 compendium released by SHEA and IDSA has a 4 Es section. This compendium summarizes the literature on effective strategies to engage senior leaders and staff, to execute an implementation plan within a certain environment, and evaluating that effort.

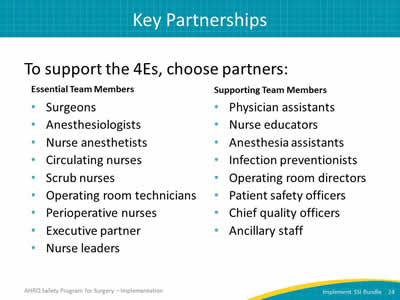

Slide 24: Key Partnerships

Say:

It takes a village to make this work happen. Create a large pool of supporters within your organization. Think broadly. Integrate a well-developed middle-level management quality improvement group with frontline staff. If there isn’t such a management-level infrastructure, then strive to add that skillset and expectation within your unit.

Think broadly within the 4 Es when mapping out how to forge key partnerships. It takes a lot of effort, and there’s a role for everyone in this work.

Ask:

Who are the strategic partners you need to engage in your organization?

Say:

Key stakeholders in the surgical arena are critical to a successful safety program for surgery. Involve surgeons both on staff and with privileges, anesthesiologists, nurse anesthetists, circulating nurses, scrub nurses, perioperative nurses, and operating room technicians. Nurse educators, physician assistants, infection preventionists, and department leaders can all offer valuable insight in implementing quality improvement initiatives. Never underestimate the value of an engaged senior executive.

Slide 25: Engage

Say:

Post infection rates and the number of patients affected by SSIs to bulletin boards. Document a number (e.g., 10 patients in the last quarter) to make it real for staff. Find out whether staff members know about or understand their surgical site infection rates. Before they can own the rates, they have to be aware of the rates.

Share stories about how SSIs affected the patient’s life, his or her children, family, and their job. These devastating stories are exceedingly effective at initiating change. Stories elicit emotions, change minds, and facilitate change in behavior.

Use the audit tool to present SSI cases to leadership, staff, and the infection control community. These tools will reveal the evidence-based therapies–therapies that could have prevented SSIs–not provided to the patients with SSIs.

Highlight staff members that ensure patients receive the evidence-based therapies.

Teach and emphasize that these infections are preventable. At this point in the safety program, this may seem like old news to you. That is not the case for all of your frontline providers. Be vigilant. Often, in spite of efforts to communicate infection rates, frontline staff may still lack awareness of the rates. In fact, frontline staff may not realize that reducing SSIs is an organizational priority or what the reduction goals are. Tell them, as often and in as many ways as possible. Never assume they know.

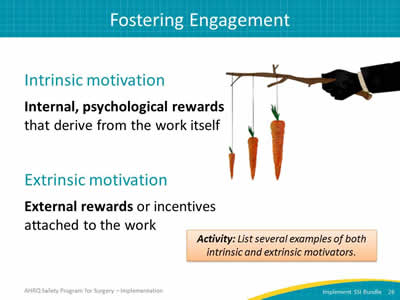

Slide 26: Fostering Engagement

Say:

People may say “we don’t have time” or “we don’t have money.” Initial quality efforts rarely have the luxury of protected time or extra funding to accomplish the goals. This is true across many organizations, but especially true in health care.

Ask:

So what options do you have if you can’t offer time or financial incentives?

Say:

Recognize and exploit the opportunities you have by tapping into other means of motivation. Intrinsic motivation refers to internal, psychological rewards that derive from the work itself. It entails the personal satisfaction of performing a job well, exceeding your own expectations, or perhaps feeling a part of something larger.

Extrinsic motivation refers to external rewards or incentives attached to the work. Salary, promotions, and praise are all examples of extrinsic motivators.

Ask:

Can you think of budget-friendly extrinsic motivators?

Say:

Use both types of motivators to engage staff members. Post team members’ names and pictures and team successes. Say thank you at a staff meeting for the dedication to quality improvement and improving patient safety. Share stories of good catches and extra efforts; share stories about your patients.

There are opportunities to understand what motivates our staff, both intrinsic and extrinsic. Ask staff for their input. Give staff opportunities to shine and showcase their work to senior leaders and throughout the organization or the community.

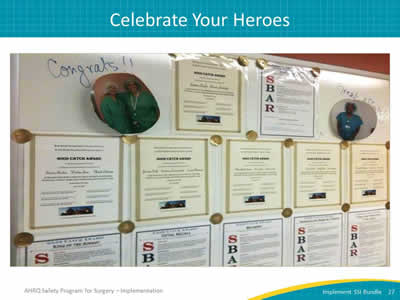

Slide 27: Celebrate Your Heroes

Say:

Celebrate your heroes. Recognize those with the courage to speak up and stop a patient from being harmed. Meeting announcements, newsletters, bulletin boards are inexpensive yet effective ways to show staff what their leaders value and, ultimately, improve safety culture.

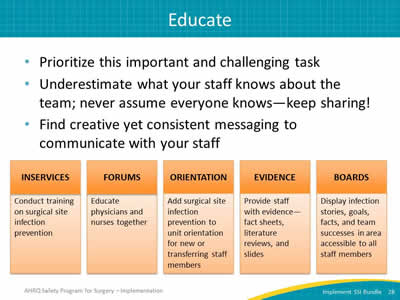

Say:

Offer staff many opportunities for education. Not all clinicians can join an event. If your goal is to ensure that all providers perform appropriate preoperative skin preparation, then provide multiple opportunities for sharing and discussing the guidelines. Prioritize educating staff on the expectations.

This next point cannot be stressed enough. Always underestimate what your staff knows about the team’s goals or progress. Never assume everyone knows or that the information is old. Generally, staff members have far less exposure to priorities than expected. Keep sharing information in multiple arenas and formats.

Find creative ways to communicate. A few moments ago we referenced meeting announcements, newsletters, and bulletin boards. Other ideas involve posts in the break room, posts in the restrooms, and treats to celebrate successes.

One team encouraged people to tell the team story to a coworker. If that coworker could answer a question or two about the team or intervention at a staff meeting, both received a small prize. This was a great example of education engaging (two Es with one action).

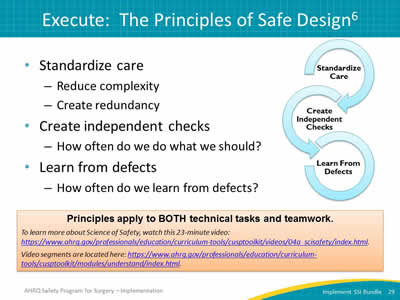

Slide 29: Execute: The Principles of Safe Design

Say:

Principles of safe system design, a feature of high-reliability organizations, focus on systems rather than individuals. We need to build a system that makes it easier for providers to do the right thing and harder for providers to do the wrong thing.

Consider this example:

If a provider wants to order an antibiotic for a patient who may be septic, the ordering system could prompt with a couple of questions and then recommend a particular antibiotic. If the provider agreed and selected the recommendation, the antibiotic would then be ordered.

If the provider does not agree with the antibiotic selection, that would be OK. However, the provider would then need to provide additional information for the requested selection. The provider would retain autonomy. This additional step in the ordering system encourages consistent care. It also encourages evidence-based care rather than individual preference, as well as strengthens the system.

Ask:

How can you standardize work to make it easier for providers to do the right thing?

What independent checks can you create?

The principles of safe design apply to BOTH technical tasks and teamwork.

To learn more about Science of Safety, watch this informative 23-minute video: http://www.ahrq.gov/hai/cusp/modules/understand/index.html.

Video segments are located at: https://www.ahrq.gov/hai/cusp/modules/understand/index.html.

Slide 30: Briefings and Debriefings

Say:

Briefings and debriefings have been linked to reductions in communication breakdowns, operating room delays, communication-related disruptions, nursing time spent away from the patient’s bedside, operating room traffic, and SSIs. It also reduces nursing time spent in the core, or the sterile room where surgical supplies are stored. Mortality rates drop also if briefings are done well. Briefings and debriefings result in improved communication and teamwork.

Slide 31: Briefings and Debriefings

Say:

After you have built your intervention bundle around the areas that you want to focus on, use the briefing and debriefing tools to support efforts to resolve those defects. Customize your briefing and debriefing based on local defects.

This former briefing process [point to example on slide] involved a long and cumbersome form. In fact, the same form was used in all operating rooms. The process did not include followup on the comments.

Ask:

How valuable do you think the frontline providers found briefing with a long form listing issues that did not change?

Say:

Staff will not find value in the briefing process unless the time they put into it helps them do their job or helps their patients. Use briefing time to identify defects. These defects can escalate problems faced during the case and prioritize finding a solution. Use the briefing and debriefing tools to resolve issues and provide feedback.

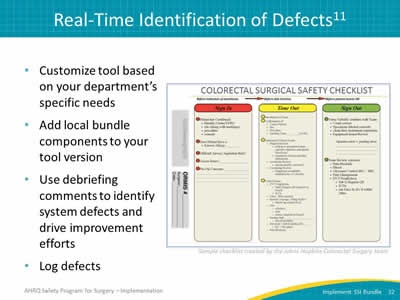

Slide 32: Real-Time Identification of Defects

Say:

Again, customize whatever tool you choose based on your specific needs. Include the components of your local bundle. Comments from your tool should help you identify defects or barriers to the interventions.

Here is an example of a tool developed by the Johns Hopkins Colorectal Surgery team.

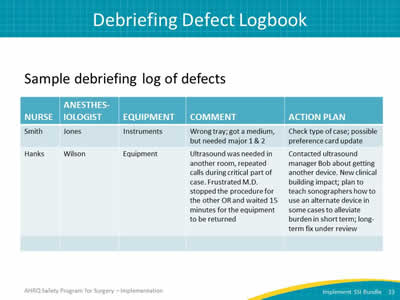

Slide 33: Debriefing Defect Logbook

Say:

Keep a log of the comments from the debriefing tool. Include the type of issue, the stakeholders, details about the defect, and the action plan. Very simple, it provides a mechanism to log defects and track progress. Share with your staff the issues identified last month or last quarter, the issues resolved, and any issues in progress and the status.

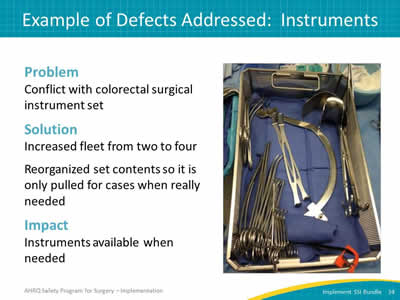

Slide 34: Example of Defects Addressed: Instruments

Say:

The colorectal team identified a shortage of instrument sets numerous times through the debriefing process. Based on the recorded evidence, the team was able to advocate for expanding the fleet. Without the documented track record of multiple cases impacted by missing equipment, the hospital had not prioritized the request for additional resources.

Slide 35: Evaluate

Say:

The last of the 4 Es is to evaluate. Staff members need to know if their efforts are making a difference. One option is to track SSI rates over time to identify trends, an outcome measure. Other evaluation methods involve evidence-based auditing and SSI investigation tools, or tracking process measures.

Regardless of outcome or process measures data, post your progress in the unit and discuss during staff meetings. Once staff is aware of their rates, they will begin to own that performance data. Acknowledge and celebrate your success.

Slide 36: Key Points

Say:

In summary, briefings and debriefings provide an evidence-based strategy to standardize care and create independent checks.

Successful interventions require more than compliance; they require engagement.

Customize tools to address your defects, your goals, your surgical setting, your vocabulary, and your work processes.

After the debriefing, close the loop to solve any defects at the system level. Make sure the frontline providers have visibility of these efforts.

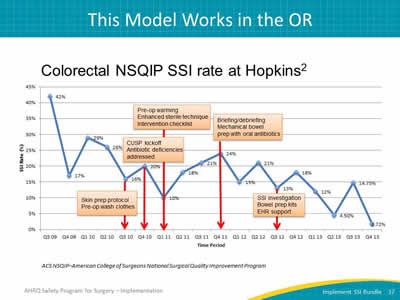

Slide 37: This Model Works in the OR

Say:

Briefing and debriefing work. This chart was introduced earlier in this safety program. It shows the significant drop in surgical site infections achieved in colorectal surgeries at Johns Hopkins Hospital. Let’s take another look at it. The journey to eliminate SSIs incorporated many interventions.

Ask:

What occurred around the middle of the timeline?

Say:

Briefing and debriefing was reintroduced with a new tool and feedback process. This allowed the safety team to record defects that impacted the current case. It also provided an opportunity for teams to revisit the implementation of previous interventions. The debriefing process raised awareness and accountability for the delivery of care and provided a forum to share the expectations within the surgical unit. Briefing and debriefing work.

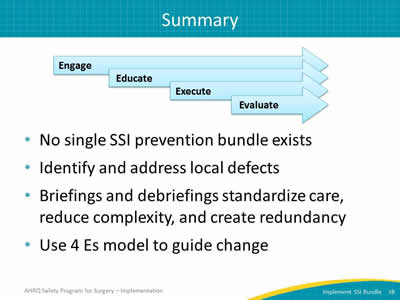

Slide 38: Summary

Say:

Each surgical unit may need to address different defects. No single SSI prevention bundle exists. Identify and focus on the defects in your surgical unit.

Briefings and debriefings standardize care, reduce complexity and create redundancy. The 4 Es model (engage, educate, execute, and evaluate) will guide your change efforts.

Slide 39: Recap of Learning Objectives

Say:

This module covered developing an implementation plan for your SSI prevention bundle. We talked about identifying and addressing local barriers that hinder the implementation of your bundle. The BIM tool was introduced to systematically identify and address the barriers to eliminating surgical site infections.

Slide 40: References

Slide 41: References