The Science of Improving Patient Safety and Identifying Defects: Facilitator Notes

AHRQ Safety Program for Surgery

Slide 1: The Science of Improving Patient Safety and Identifying Defects

Say:

The topic of this module is the science of patient safety. The discussion will include the importance of understanding system design, the principles of safe design, and the wisdom of crowds—that is, valuing the diverse input of team members.

Slide 2: Learning Objectives

Say:

This module will help you develop a systems view of patient safety. After reviewing this module, you will be able to—

- Educate your team and executive partners on the Science of Safety.

- Identify defects within your operating room by administering the Perioperative Safety Staff Assessment, or PSSA.

- Distribute and share PSSA results with your safety team.

- Locate resources on the program Web site to complete the above tasks.

- Apply Science of Safety to your work.

Share what you’ve learned with your team.

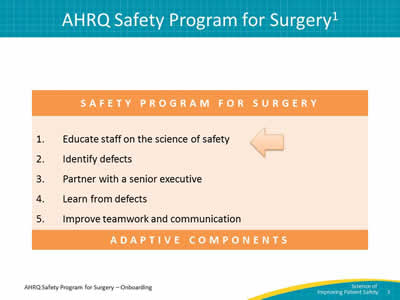

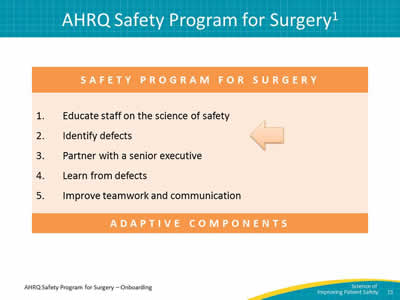

Slide 3: AHRQ Safety Program for Surgery

Say:

As the arrow indicates, we are at the first step: educating frontline staff on the science of safety. Today we will discuss how to use system lenses to uncover hazards and defects with the use of PSSA.

I’d like to call your attention to the phrase at the bottom of the box, “adaptive components.” Let’s review what we mean by technical and adaptive work. Technical work refers to challenges with an evidence-based solution. For instance, using a guideline or recommendation, we can create a checklist, protocol, or procedure to achieve a desired result.

Adaptive work, a term coined by Ron Heifetz, refers to achieving the behavior change required to effectively put protocols, procedures, and other interventions into place. For many reasons, adaptive work is challenging.

Adaptive work requires a partnership between the frontline and the executive levels. This program aims to provide strategies that support adaptive work so that technical efforts can be successful.

Slide 4: Advances in Medicine: Lingering Contradictions

Say:

We have made tremendous advances in medicine. Most childhood cancers are now curable. Once considered a death sentence, AIDS is now a chronic disease, and we can now expect to live longer than our parents and grandparents. Despite these advances, instruments and sponges are still left inside patients undergoing elective surgery. Hundreds of thousands of patients develop healthcare-associated infections that can prolong their stay, complicate their treatment, and even take their lives. These defects are as much a part of our health care systems as are the innovations.

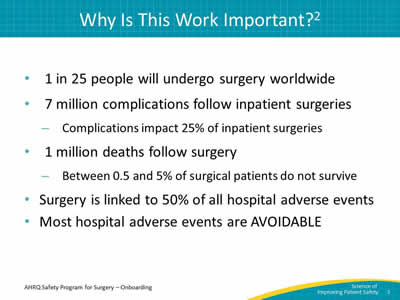

Slide 5: Why is This Work Important?

Say:

The safety of surgical care is of significant public health importance worldwide. Annually, there is roughly one operation for every 25 people worldwide. Twenty-five percent of inpatient surgeries result in a complication, and about 1 million deaths occur after surgery.

In addition, surgery is linked to half of all hospital adverse events. Most hospital adverse events are avoidable. This safety program for surgery will help hospital teams build capacity and learn new skills. These skills are required for changes that will result in safer surgical care.

Slide 6: How Do These Errors Happen?

Say:

When we treat medicine and health care delivery as a science, rather than an art, providers can focus on health care delivery processes using evidence-based practices. In order to do this effectively, providers must develop or improve the ability to learn from mistakes and implement procedures that reduce the risk of the future occurrence of errors.

Errors also occur because systems frequently are not designed to catch mistakes before they reach the patient. When we design processes using standardization, such as checklists, and create independent checks for key processes, we improve our ability to reduce the risks of adverse events resulting in harm.

Slide 7: Educate Staff on the Science of Safety

Say:

Science of safety training helps providers recognize that most errors arise from the way our health care systems are organized. A systems thinking approach considers the organization of and interaction between individuals, resources, equipment, information, and other elements as we work toward a goal.

Here are the primary concepts of science of safety. We will cover these concepts in more detail.

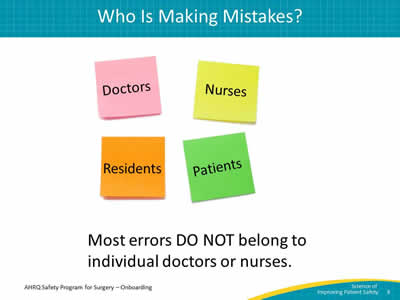

Slide 8: Who Is Making Mistakes?

Say:

Errors happen because people are fallible. Often we overlook this fact of human nature, expecting perfection from health care providers. By accepting that people are not perfect, we are taking the first step toward realizing that medical errors, in large part, don’t belong to individual providers, but rather are a product of how our health care systems are designed. When we focus on systems, rather than individuals, we realize that we can redesign care and delivery processes to improve care and minimize the occurrence of errors and adverse events.

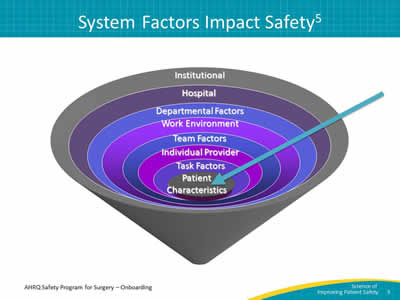

Slide 9: System Factors Impact Safety

Say:

This image is adapted from the work of Charles Vincent and his colleagues. It shows the continuum of system factors that can influence health care delivery and the occurrence of adverse events and other defects. We need to consider these factors when we respond to defects or otherwise make desired changes.

Science of safety training shows staff how to consider the impact of each of these factors on the delivery of care. By developing a systems point of view, we realize that, at any given time, multiple system factors may simultaneously influence care delivery and patient safety. These factors range from hospital and institutional factors such as facilities and budgetary constraints to ways we work together as a team, the attributes of the tasks we complete, and patient characteristics such as cognitive ability, level of awareness, and language barriers.

Slide 10: Safety Is a Property of the System

Say:

This video illustrates using system lenses.

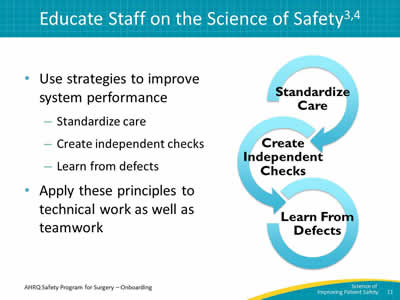

Slide 11: Educate Staff on the Science of Safety

Say:

There are three principles of safe design. Standardize care where possible, create independent checks, and learn from defects. These principles apply to both the technical and adaptive components of change.

Examples of standardization include checklists and standardized team training. Creating independent checks for key processes allows teams to focus on patient care and provides a roadblock, alerting us to accidental breaches in protocols or policies. Learning from defects is a powerful exercise in which teams evaluate their processes to identify gaps that allow mistakes to happen. This evaluation provides the means to identify interventions that can reduce the risk of future adverse events.

Slide 12: Standardize When You Can

Say:

In this video, we learn more from Dr. Peter Pronovost about the value of standardization.

Slide 13: Create Independent Checks

Say:

This video illustrates the power of creating independent checks for key processes.

Slide 14: Educate Staff on the Science of Safety

Say:

Teams make wise decisions with input from a variety of viewpoints including unit providers, colleagues, patients, and family members. This requires a culture where frontline providers feel comfortable speaking up and have confidence their concerns will be addressed. Health care works best when all team members are ready, willing, and able to commit to delivering the highest quality patient care. We all see the world differently, and the diversity of background, experience, and training that exists in any health care team provides a wealth of knowledge and skill that we should tap into as we seek to deliver high-quality patient care.

Science of safety training helps providers and others understand that the majority of errors arise from the way our health care systems are organized. A system approach teaches us to consider both the organization of and interaction between individuals, resources, equipment, information, and other elements, as we work toward a goal.

Slide 15: AHRQ Safety Program for Surgery

Say:

Once teams are educated about the science of safety, the next step involves identifying defects.

Ask:

How will you engage your busy frontline staff as you educate them on the science of safety?

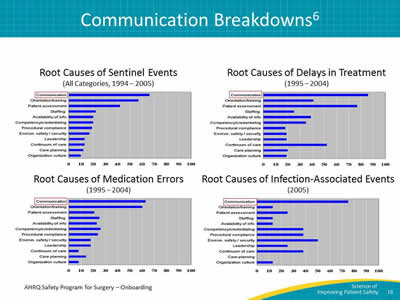

Slide 16: Communication Breakdowns

Say:

According to the Joint Commission, communication breakdowns are a significant, if not leading, cause of many undesirable outcomes, including sentinel events, medication errors, delays in treatment, ventilator events, and healthcare-associated infections.

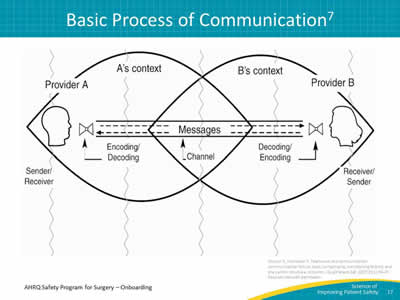

Slide 17: Basic Process of Communication

Say:

Communication in health care can be challenging, requiring senders and receivers of communications to consider each other’s contexts as they interpret messages in rapidly changing and stressful situations. Developing awareness of the factors that influence communication for both the sender and the receiver helps teams develop environments that facilitate communication and feedback among team members. Many organizations have spent an enormous amount of effort implementing standardized communication tools to minimize the possibility of communication errors.

Slide 18: What Is a Defect?

Say:

Simply put, a defect is any clinical or operational event or situation that you would not want to happen again—an unsafe condition, a patient fall, a venous thromboembolism, a medication error, a surgical site infection, wrong-site surgery, missing equipment, nursing time spent away from the bedside, et cetera. Anything that might lead to preventable patient harm is a defect.

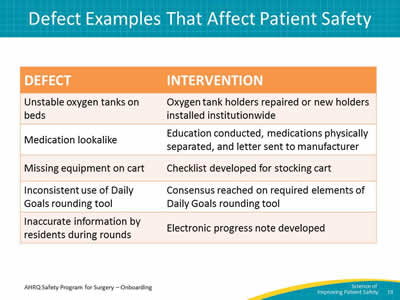

Slide 19: Defect Examples That Affect Patient Safety

Say:

These examples of defects that affected patient safety and the interventions put in place to alleviate them were identified by fellows in anesthesiology and critical care medicine.

The chart is divided into two columns: Defects are listed on the left, and each defect’s potential intervention is located on the right.

For the defect of unstable oxygen tanks on beds, a potential intervention is that oxygen tank holders were repaired or new holders were installed institutionwide.

For medication lookalikes, staff were educated about medication similarities and the physical separation of drugs, and staff sent a letter to a drug manufacturer to request different labeling.

Missing equipment on a cart: Staff developed a checklist to assign responsibility for stocking supplies on the cart.

Inconsistent use of Daily Goals Checklist tool during patient rounds: The staff reached consensus regarding the elements of the tool to be applied during rounds.

Residents report receiving inaccurate information during rounds: An electronic progress note system was developed to maintain accurate information exchanges on the unit.

Slide 20: How Can Your Team Identify Defects?

Say:

Here is a list of some ways through which defects can be identified. We’re used to thinking about event reporting systems, liability claims, sentinel events, and mortality and morbidity conferences when we want to identify defects that occur in our clinical areas. The Perioperative Staff Safety Assessment, which is an effective and proactive tool for identifying defects, adds direct communication with frontline providers.

Slide 21: PSSA Taps Wisdom of Frontline Providers

Say:

The Perioperative Staff Safety Assessment taps into the wisdom and knowledge of frontline providers in the perioperative area and uses that knowledge to guide efforts to improve safety. In leveraging staff member knowledge, the PSSA allows teams to determine risks that have jeopardized or could jeopardize patient safety on a unit. Frontline staff members are the eyes and ears of patient safety. They can list valid improvement opportunities and focus your safety program activities.

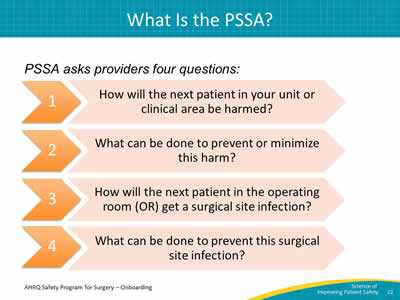

Slide 22: What Is the PSSA?

Say:

The Perioperative Staff Safety Assessment asks providers to complete four questions about the issue of patient safety in their clinical area. This simple tool asks:

- How will the next patient be harmed?

- What can we do to prevent that harm?

- How will the next patient in the operating room get a surgical site infection?

- What can we do to prevent the surgical site infection?

Please note that the tool does not ask how an individual provider will harm a patient but rather, seeks to identify threats in the patient clinical area that can result in harm and HAIs.

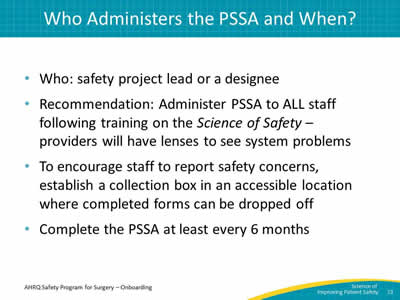

Slide 23: Who Administers the PSSA and When?

Say:

We suggest that you introduce the PSSA immediately following the science of safety training, when staff is engaged. Timing the PSSA to follow this training allows frontline staff to apply their newly developing system lenses to their own work area. Consider establishing a collection box or envelope where staff can submit completed PSSAs with some anonymity.

We recommend completing the PSSA at least every 6 months. Some clinical areas use an ongoing process in which forms are readily available so staff members can complete the PSSA whenever they have something to report. You and your team will find a system that works best for you.

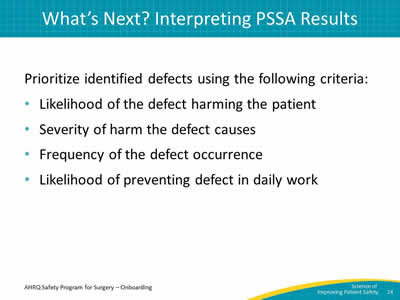

Slide 24: What’s Next? Interpreting PSSA Results

Say:

As you start this work, you can use the criteria identified on this slide to prioritize your efforts. When teams start to use the PSSA, we often recommend that they start with the low-hanging fruit to allow them to develop their skills on easily solvable problems.

It’s also important that those who respond to the PSSA see that their efforts result in improvements.

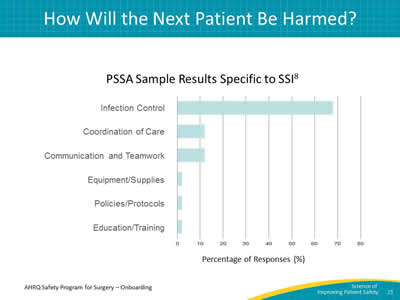

Slide 25: How Will the Next Patient Be Harmed?

Say:

This slide summarizes results from a Staff Safety Assessment completed by the Hopkins colorectal surgery quality improvement team. As you can see, nearly 70 percent of respondents identified infection control as a source of risk for patients.

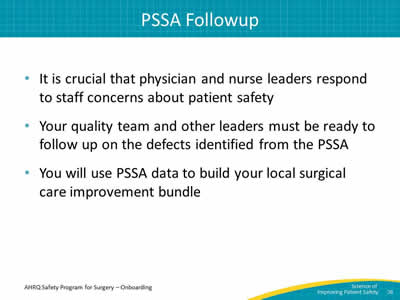

Slide 26: PSSA Followup

Say:

As with any reporting mechanism, it’s important to ensure that the completed PSSAs are not falling into a black box where the forms go in but where no results are ever visible.

The team and other leaders must be ready to follow up on the defects identified, and frontline staff must be involved in the change process. In addition, as your team works to develop an SSI improvement bundle, those efforts should be informed by the defects identified on the PSSA.

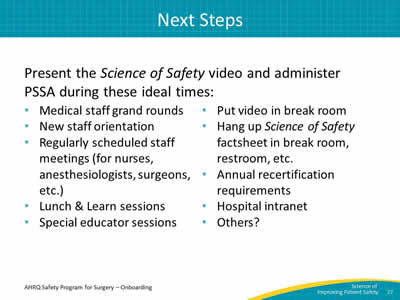

Slide 27: Next Steps

Say:

The next step for your safety team is to train your staff members on the Science of Safety. We know it can be difficult to reach the staff members who work in the perioperative area. This slide includes venues for training that a team at Johns Hopkins used with success. This list is not exclusive or exhaustive. It’s important to consider and plan how you will train staff and others who work off hours such as the overnight shift, new employees, and residents and house staff, if you have them. You may also consider using incentives such as raffling off gift cards, candy, or other treats to those who complete the training.

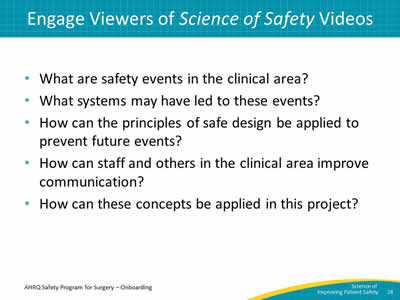

Slide 28: Engage Viewers of Science of Safety Videos

Say:

A good way to engage staff is to ask them to apply the systems lenses they’re developing to their own work area. Consider asking some of these questions in meetings and during other teachable opportunities.

Ask:

What are safety events in the clinical area?

What systems may have led to the events?

How can the principles of safe design be applied to prevent future events?

How can staff and others in the clinical area improve communication?

How can these concepts be applied in this project?

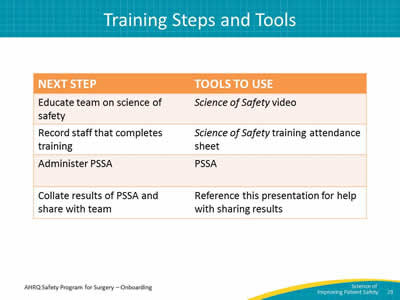

Slide 29: Training Steps and Tools

Say:

Now that you’ve seen the importance of educating staff on the science of safety, we’d like to provide you with some resources.

You can access a video discussing the science of safety that you can share with your teams. We also highly recommend that you use the slides and facilitator notes from this Science of Safety module as a resource. Adapt them in ways that suit your needs.

You might also consider developing handouts, posters, or newsletter articles to help introduce and reinforce the concepts you’ve learned about.

Slide 30: Recap of Learning Objectives

Say:

After reviewing this module, you will be able to develop a systems view of patient safety through the following actions:

- Apply Science of Safety into your work.

- Educate your team and executive partners on the Science of Safety.

- Identify defects within your operating room by administering the PSSA.

- Distribute and share PSSA results with your team.

- Locate resources on the program Web site to help complete the above tasks.

We ask that you share what you’ve learned with your teams.

Slide 31: Lessons Learned

Say:

To review the main components of this module, consider these thoughts:

Every system is designed to achieve its anticipated results.

The principles of safe design are: standardize when you can, create independent checks, and learn from defects.

Teams make wise decisions when they have diverse input.

The Perioperative Staff Safety Assessment helps teams identify defects that the team can address, and helps teams design interventions that prevent the defects from occurring in the future.

Slide 32: References

Slide 33: References