Engaging Senior Executives: Facilitator Notes

AHRQ Safety Program for Surgery

Slide 1: Engaging Senior Executives

Say:

In this module we will discuss the importance of senior engagement on your safety program team.

Slide 2: Why Do We Need an Executive?

Say:

Sometimes getting executives involved in a patient safety project is one of the most challenging aspects of the project.

Tip: The Perioperative Staff Safety Assessment, or PSSA, is often referred to as the two-question survey. It asks frontline providers the following:

- How will the next patient be harmed?

- What can you do to prevent that harm?

Ask:

Have you ever been a part of safety and quality improvement efforts that were undermined by very small things (like the temperature probes in the example) outside of your control?

Say:

Most of us have. And that is where the executive partner can help immensely by seeing the larger picture.

Slide 3: Learning Objectives

Say:

Sometimes getting executives involved in a patient safety project is one of the most challenging aspects of the project. After reviewing this module, you will be able to—

- Explain the difference between work on the Surgical Care Improvement Project, or SCIP, and safety program work from the executive perspective.

- List common barriers to executive engagement in improvement work.

- Apply successful strategies for engaging your executive in this program.

We ask that you share what you have learned with your team.

SCIP is a national partnership of organizations committed to improving the safety of surgical care through the reduction of postoperative complications. These complications can take a toll on patients' health and safety and can extend postoperative hospital stays or care.

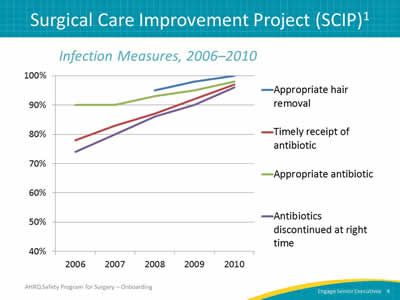

Slide 4: Surgical Care Improvement Project (SCIP)

Say:

As this chart shows, we have made remarkable progress nationwide in specific measures to improve surgical care and reduce surgical-site infection, like giving the right antibiotic at the right time or clipping the hair instead of shaving the skin prior to a surgical incision as part of SCIP. Yet for the most part, these improvements have not translated into reduced infection rates or improved outcomes.

Ask:

Why might that be?

Say:

There are at least two important reasons. First, surgical site infections are exceedingly complex, and there are likely many defects, in addition to the SCIP measures, that come into play. For example, preventing surgical site infections is not just about giving the right antibiotic at the right time, but also about making sure patients receive the right dose of antibiotic and/or that those antibiotics are appropriately redosed. Similarly, we need to go beyond asking whether skin was shaved.

Ask:

Are we using the right agent for skin prep?

Is the quality of skin prep appropriate to prevent surgical site infections?

Say:

The second reason these improvements have likely not translated into improved outcomes is that, for many hospitals, SCIP has become an exercise in “checking the box.” We often align our documentation, for example, to meet SCIP criteria. But for these improvement efforts to be successful, it takes much more than checking boxes. Our frontline staff needs to be engaged and to find value in its work. Until our staff is engaged rather than simply compliant when it comes to checking boxes, our patients are unlikely to see better outcomes despite our continued focus on SCIP measures.

Legend notes:

Appropriate hair removal

Surgery patients needing hair removed from the surgical area before surgery, who had hair removed using a safer method (electric clippers or hair removal cream, not a razor).

Timely receipt of antibiotic

Surgery patients who were given an antibiotic at the right time (within 1 hour before surgery) to help prevent infection.

Slide 5: Surgical Care Improvement Project (SCIP)

Say:

Nationwide, SCIP rates have increased, showing remarkable progress in compliance, including these measures:

- Giving the right antibiotic at the right time.

- Discontinuing antibiotics at the right time.

- Clipping the skin as opposed to shaving the skin.

Yet these improvements have not reduced infection rates or improved outcomes.

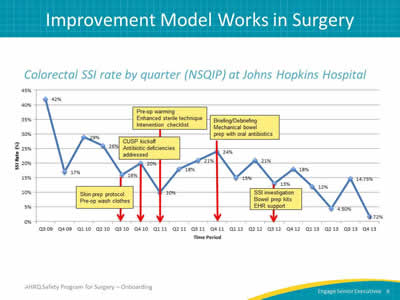

Slide 6: Improvement Model Works in Surgery

Say:

Evidence shows this approach works. At Hopkins, for example, this approach has been used with the support of anesthesia, nursing, and surgical leadership. They asked staff members how the next patient will be harmed and what can be done about it. Combined with emerging evidence and local opportunities identified through auditing performance, Hopkins was able to achieve a 33 percent reduction in colorectal surgical site infection rates.

The colorectal data was based on the NSQIP definitions for surgical site infections, or SSIs. NSQIP refers to the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program.

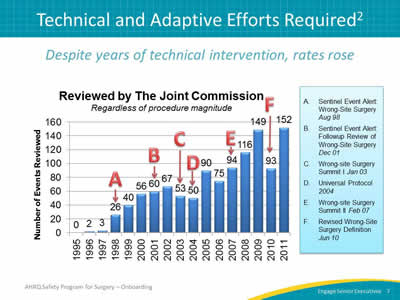

Slide 7: Intervention Requires Technical and Adaptive Efforts

Say:

Despite numerous technical approaches to improve wrong-site surgery corrections, the number of events The Joint Commission reviewed rose from 1995 to 2011. Teams must also address adaptive issues to achieve lasting intervention.

Technical work is the long list of evidence-based practice, and includes interventions we know we should do to prevent complications—such as giving the right antibiotic at the right time and appropriately prepping the skin prior to incision. Many organizations have worked for years to standardize care and incorporate these interventions into local policies, protocols, and checklists to help ensure patients receive the therapies they should. These checklists are helpful tools, but they only work if the staff is engaged to use them.

Adaptive work is the “intangible” components of work, like ensuring operating room or OR team members hold each other accountable for quality skin preparations. Adaptive work addresses the attitudes, beliefs, and values of clinicians that drive behaviors, norms, and processes within our organizations and ORs. Addressing adaptive challenges is often much more difficult; checklists alone will not improve teamwork or your safety culture.

Slide 8: Executive Engagement Stories

Say:

We know that learning from example can be very powerful. Next we will share a few stories about how frontline teams have partnered with executives to make a difference for patients and for perioperative staff and providers. Some of these will be small fixes, but even these relatively small things can be difficult to change without support and involvement from the leaders who understand the administrative system AND have the authority or influence necessary to get changes into place.

Ask:

As we go through these examples, think about improvement initiatives you’ve been a part of.

Do you have examples of successful executive partnerships?

If so, what did they look like?

What role did the executive play?

How did you manage that relationship?

If not, can you think of an example of when executive leader involvement could have made a big difference for your efforts?

Slide 9: Case Study: Laparoscopic Surgery Trays

Say:

We also know that this effort of reaching out and tapping into the frontline staff can have additional value. As part of this safety program, one of the steps is asking your frontline staff what they think can be done to improve care. In today’s environment, that is exceedingly important. Frontline surgical staff at The Johns Hopkins Hospital pointed out several things that increased value and efficiencies, some not directly related to surgical site infections.

For example, the staff appropriately pointed out that every single colorectal or laparoscopic gastrointestinal surgical team had to open and process a tray that included more than 137 instruments, many of which were never used. There was an opportunity to reduce costs and improve value. By partnering with senior leadership through this safety program teamwork process, Hopkins created a new tray with 60 percent fewer instruments and reduced costs and saved time.

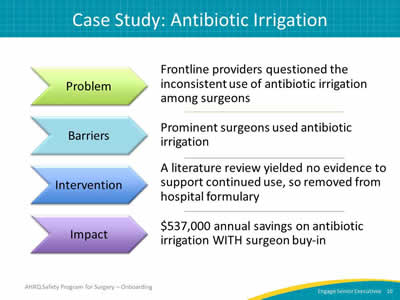

Slide 10: Case Study: Antibiotic Irrigation

Say:

Here is another powerful example of the benefits of tapping into the wisdom of the frontline staff beyond just SSI prevention.

In the second step, Hopkins asked its teams how to improve care. Teams responded by asking why some surgeons use an antibiotic irrigation within the abdomen and some surgeons don’t. An extensive literature review found no evidence supporting the use of that irrigation. Through the partnership with senior leadership, the team removed antibiotic irrigation products from the formulary, recognizing an annual savings of more than $500,000. Most remarkably, Hopkins achieved this change by working WITH the surgeon team and gaining surgeons’ buy-in on the current lack of supporting evidence for antibiotic irrigation.

This safety program incorporates the exceedingly important adaptive measures that both allow staff to share observations and provide a forum for open discussion. Before the irrigation products were removed from the formulary, the surgeons weighed in with their views and experiences and responded to the literature. Because surgeons were involved in the process and the decision to discontinue antibiotic irrigation, even the surgeons previously using the irrigation products accepted and even embraced the discontinuation. That is the power of this safety program and CUSP. Of course, the half a million dollars saved each year doesn’t hurt either.

Slide 11: Barriers to Executive Engagement

Say:

This safety program empowers frontline staff rather than taking a top-down hierarchical approach.

Many of you may have strong executive partnerships in place already. They are becoming more common. If you have an executive partner, you may also have experienced some of these challenges. If an executive partnership is a new relationship for your team, these issues might surface as you work to recruit and engage an executive.

First, this program includes a structured process, but it is less prescriptive than some initiatives.

It involves “building your own bundle” and not implementing an “off the shelf” set of rules or instructions. We’ve found that there isn’t one solution that will fit everyone’s needs.

Second, as the surgical safety program is about culture change as well as technical improvement, this process emphasizes input from all levels and types of expertise in the perioperative area. Most executive leaders want to have this type of culture—in which everyone feels comfortable speaking up, participates, and believes they have input valuable to the team. However, not all leaders are great at building this culture. It can be difficult, and very few people are trained on how to do it. Leaders are expected to lead and make decisions. However, in safety program teams, the executive is only one of many perspectives represented in decision making.

Third, the executive partner is a core member of the team, but is not there to lead the team. This may be an unusual role for an executive, but that person is there to support frontline team members, who have the best understanding of how their system works and how it can be improved. Many executives are in the habit of “running the show,” and that habit can be tough to break. In much of their work, they are expected to lead the way, but this team has different expectations. We ask them to support, coach, mentor, provide guidance, and help connect the team to the broader organization’s goals and priorities as well as allocate necessary resources (time, personnel, equipment, supplies, et cetera).

Fourth, the surgical safety team requires a cross-functional approach to problem solving and critical thinking. The team will identify safety-related priorities on the unit and work to solve them. Real solutions almost always require input from everyone. We aren’t all used to working in this setting, and coming to a common understanding of the problem and why different solution options may or may not be viable for everyone can take additional upfront time.

Fifth, you don’t necessarily know what’s coming in safety program work. In many ways, a good team will encounter surprises along the way. The work will uncover new insights into how the unit works, what the challenges are, and what solutions are needed. It is much easier to engage someone (anyone, not just executives) if you can be clear about what will happen.

Ask:

Which of these barriers have you experienced in your work? How did you overcome them? We’ll talk about approaches to address these barriers throughout the rest of the module.

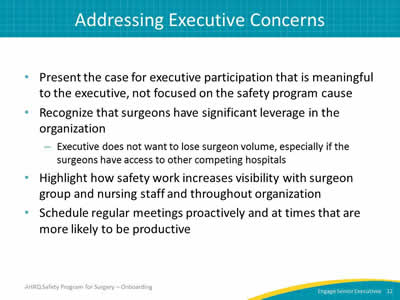

Slide 12: Addressing Executive Concerns

Say:

Like the rest of us, executives have many competing priorities. Many people in the organization ask for their time. So, we need to make a compelling case that participating in this safety program is both necessary and valuable.

Ask:

What do you think your executive leaders value and prioritize most?

What do you think drives their decisions about how they allocate their time and effort?

Say:

When we work in multidisciplinary teams, it’s important to understand other people’s perspectives and priorities. We want the executive to better understand the pressures and challenges frontline teams face, but we also have to take the executive’s perspective to understand his or her work and ways the team can support the executive’s goals. Partnering with executives or anyone else is not a one-way street. When we think about engaging people in our work, we need to start from where they are and highlight ways different stakeholders will benefit.

While everyone’s organization will be a bit different, here are some common realities to think about when reaching out to executive partners.

Ask:

Do you think the executive would be interested in strengthening relationships with the surgeons?

Say:

Whether you have an employed physician model or whether surgeons are seen as the “customers” for operating room time, most executives will be interested building a closer working relationship with surgeons.

Second, this point extends to all staff. Executives are increasingly aware that developing a safety culture is a part of their job. This awareness requires them to be more visible and accessible to frontline staff. The CUSP components of this safety program can be a way to make this happen in a structured, predictable, and solution-focused way. Executives can be seen in a positive light and can accomplish their goals in an efficient way.

Third, schedule meetings far in advance and at times the executive can attend. Be aware of recurring demands on the executive’s time and work around them. For example, don’t schedule a team meeting the afternoon before a monthly board meeting; executive attention will be diverted to meeting preparations.

But scheduling regular meetings the week before high-level meetings will provide executive with great information and perhaps excitement to share. Avoid scheduling conflicts such as meetings that regularly run over, tend to be acrimonious, or are particularly intense. Executive attendance and attention will be ongoing challenges if these logistics are ignored.

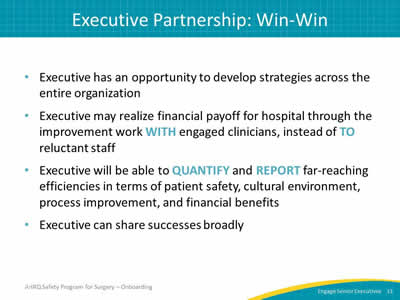

Slide 13: Executive Partnership: Win-Win

Say:

Another way to view the senior executive partner is as a liaison to other leaders. In most if not all hospitals, no one person has supreme authority over all aspects of the organization. Your work likely will touch many interrelated departments, processes, and policies. It can be a challenge for frontline staff and unit-level leaders to recognize all stakeholders. Executive partners usually do have that knowledge and hopefully working relationships with these different leaders. For example, in the colorectal surgical safety team at Hopkins, the executive partner also served as a broker as well—reaching out to and involving other leaders as the project required.

This is similar to the idea of rotating in different types of clinical expertise as the focus of your team evolves over time. For example, if you are working on infection issues, infection prevention needs a strong presence. If you are working on medication-related issues, pharmacy should be a key player. The same is true of executive leaders. When the team’s focus includes an area of the organization, the executive leader of that area should be engaged at some level.

Safety work has some additional benefits that executives recognize. In many ways, safety teams are engines of innovation. They identify problems and generate solutions. As they implement and evaluate, they find out what works. These lessons can be shared broadly across the organization. The executive can play a key role in this transition from a local solution to something the system as a whole can benefit from. This knowledge sharing and innovation is necessary to keep pace with the rate of change in health care today. Executives are well positioned to share these stories within and outside of the organization, as well as vertically and horizontally within the organization, such as at department meetings, executive meetings, board meetings, industry conferences, and local business networking events. This storytelling is a key approach to managing culture in an organization because it demonstrates and reinforces the values and capabilities of the organization. Use it.

Ask:

Currently, do you have mechanisms to systematically capture and share lessons learned and successes in safety and quality improvement?

Say:

Your safety program work can be a key component of this infrastructure.

Slide 14: What Does an Executive Offer?

Say:

We’ve spent a good deal of time discussing what the executive may get out of participating on your team.

Ask:

But what’s in it for the team?

Say:

Many things. As we’ve discussed in the examples above, the executive serves to support the frontline team with guidance, advice, connections to other stakeholders, and material resources when necessary. In particular, the senior executive brings an alignment with the broader goals of the organization. The connection with other stakeholders can open lines of communication and reduce perceived barriers to improvement efforts.

Slide 15: Engaging Your Executive

Say:

Be clear with requests. If your executive is actively engaged in your team meetings, the need for a resource should be clear, and hopefully your executive was a part of the discussion delineating that need. But before you ask an executive for a resource, whether time or materials, clarify exactly what you are asking for.

Be prepared with evidence to support your requests. Make sure your senior executive has the information necessary to make an informed decision or present the request to a higher authority. Decisions over a certain expenditure amount very well may require additional support. Proper preparation will allow your executive to proceed with confidence and support.

Through tools like the PSSA, this program is all about anticipating obstacles and problem solving. The same is true for this aspect of the project. Anticipate obstacles and relevant solutions for any resource request. Keep momentum moving forward by anticipating and answering these questions.

Do not expect a decision immediately. Be clear about the deadline for a decision and provide alternatives where possible. The executive is not an all-powerful magician. Give the executive the chance to build organizational support and resources for major decisions.

Slide 16: Executive Safety Rounds

Say:

Preparation is the key to success.

Slide 17: Preparation Is Key to Success

Ask:

What does it look like to have an executive partner on your team?

Say:

We have to overcome the notion that there’s sanctity to that yellow line that keeps anyone who’s not a surgeon or a clinician who’s actually worked in the OR space from contributing to its functioning. Increasingly, executives across the country are not only willing to cross the line to come in and see you in your space, they’re eager for you to invite them to do just that.

A little preparatory work can make executive engagement easier to maintain. Executives remain engaged when their time is valued. Before the first perioperative tour, share unit-specific information with the executive. The additional context will make the tour more meaningful and will likely allow for deeper questions and engagement.

Plan the monthly executive safety rounds with a time buffer for the entire year. Be respectful of the executive’s schedule and keep meetings on schedule. Start promptly and manage time during the meeting/tour. Be prepared to wrap up the event on schedule. Keep discussions applicable to the group; suggest topics go offline when necessary to keep the group on task.

Slide 18: Executive Safety Rounds Kickoff

Say:

Every chief executive officer or CEO in the country wants to believe that his or her hospital is the best. Sometimes being able to share data that indicate vulnerabilities or opportunities to improve gives the CEO a focus and provides a chance to see the importance of the CEO’s own role as a quality improvement and safety program team member.

A kickoff meeting can set the stage for developing this kind of understanding. Consider sharing the following at the meeting:

- Patient safety culture survey results.

- The prioritized the list of safety issues your team has compiled based on a PSSA—asking how will the next patient be harmed by a surgical site infection or surgical event and what can be done to prevent this harm.

- Unit-specific information, such as—

- Your staff turnover rate.

- Your SSI rate.

- Data from NSQIP if you participate in the American College of Surgeons, a NSQIP data process.

- Your staff’s views on what makes your OR unique and/or what your staff is proud of.

Slide 19: Executive Safety Rounds Kickoff

Say:

Step 1: Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture or HSOPS assessment composite scores:

- Share your HSOPS scores.

- HSOPS aggregate report provides composite scores graphs.

- Consider a brief safety culture summary, highlighting important points or culture score results.

Tip: Don’t be overly wedded to using “Step 1” or “Step 2,” because sometimes the tool might walk you through a series of guiding questions. Use a title that states the how-to.

Ask:

Do you know how to access your HSOPS aggregate report?

Slide 20: Executive Safety Rounds Kickoff

Say:

Step 2: Collated PSSA responses:

- Use the PSSA responses grouped by commonly identified defect categories such as equipment, teamwork, and infection control.

- Provide a table to summarize your clinical area’s safety priorities.

- Allows bird’s-eye view of safety challenges as well as meaningful evidence that familiarizes executive with concerns.

Optional: Consider building on staff’s suggestions for improvement with specific recommendations for your senior executive.

Slide 21: Executive Safety Rounds Kickoff

Ask:

For those of you with an executive partner already, how well does that person know your unit? Does he or she know your unit’s key priorities? What about your SSI rates?

Say:

Don’t make assumptions about what your executive partner knows. Share the basic structural information (number of rooms, average number of cases, types of cases, et cetera) as well as safety- and quality-related information. Have detailed information ready but provide a one- or two-page summary to highlight key features of the unit, areas of strength, and priorities from various sources (outcome or process data, culture data, et cetera).

Slide 22: Executive Safety Rounds Kickoff

Say:

It’s important that you solicit collaboration with your executives. Don’t just invite them to come to the unit and walk through the OR with you. In addition, find a space—such as the staff lounge or a conference room that you typically use—where there can be real conversation with your senior executive. Everyone should be able to take part in the conversation around this project in a nonthreatening, easygoing, and conversational way.

This doesn’t happen without preplanning and a strong and consistent communication process with the entire staff. Meetings will be far more productive with an agenda to help guide the discussion and keep the meeting on task.

Slide 23: Executive Safety Rounds Kickoff

Say:

Watch the video titled Engaging the Senior Executive found on the AHRQ Web site in the CUSP toolkit. The 6½-minute video focuses on bridging the gap between senior management and frontline providers to facilitate a system-level perspective on quality and safety challenges that exist at the unit level.

The first meeting is very important for engaging your senior executive. You can use the CEO and Senior Executive Checklist for suggested activities and talking points. The Safety Issues Worksheet for Senior Executive Partnership provides your senior executive a tool to not patient safety issues observed during safety rounds.

Finally, schedule your executive safety rounds for the next year.

Slide 24: References