Sustainability: Learning From Defects: Facilitator Notes

AHRQ Safety Program for Surgery

Slide 1: Sustainability: Learning From Defects

Say:

This module will review some concepts from Learning From Defects Through Sensemaking. It will also cover the Learning From Defects process from the perspective of sustaining your quality improvement efforts.

Slide 2: Learning Objectives

Say:

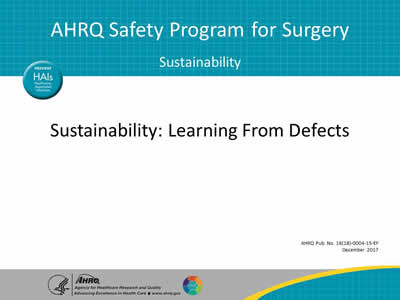

After today’s session, you will be able to—

- Describe the differences between first-order and second-order problem solving.

- Use the Learning From Defects tool to perform second-order problem solving.

- Explain how the Learning From Defect tool can be used to drive patient safety and quality improvement efforts.

- Use the four Learning From Defects questions to develop and sustain your improvement efforts.

The Learning From Defects process integrates the ongoing development of your culture of safety and quality improvement. Once your team is ready to sustain interventions, you will create a rolling process in which the team is continuously working on specific safety improvement initiatives. Some initiatives will be starting, others may be in progress or humming along, and some will be wrapping up.

Once your team is comfortable identifying system defects, eliminating contributing factors, and implementing solutions, your clinical area will develop ways to sustain those improvement efforts.

Slide 3: Recapping Our Approach

Say:

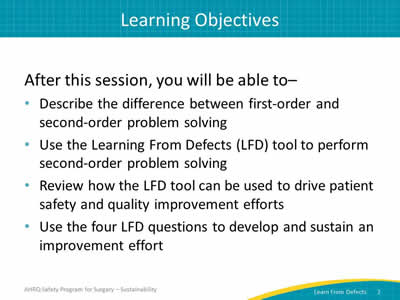

The AHRQ Safety Program for Surgery covers technical and adaptive elements. To review, technical tasks include checklists and protocols, such as preoperative skin preparation procedures. This program also addresses adaptive elements, or the values, attitudes, and beliefs that influence how our tasks are completed. The adaptive portion of the program is called CUSP, or the Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program.

CUSP includes five major points for improving safety and quality. The first step is educating staff on the Science of Safety. While most staff members receive this training during the initial phase of the project, it is worth revisiting during the sustainability phase as well. Staff members turn over, and new staff members join the clinical unit. The Science of Safety concepts are an integral part of continuously improving your culture of safety.

When new staff members join your clinical unit, make sure they have access to the Science of Safety learning opportunities that were available to original unit members. Include it in orientation sessions. Post the videos on your internal Web site. Some units prefer a slideshow presentation. Regardless of format, the information should be available for staff members. Ensure that all staff members in your perioperative space understand why the Science of Safety is important.

Next, identifying and learning from defects through sensemaking allows teams to develop interventions and proactively prevent those defects from happening. This process serves as the foundation for a long-term sustainable patient safety quality improvement.

In addition, partnering with a senior executive is imperative for prioritizing resources and interdepartmental relationships. A strong liaison with management shows frontline providers that patient safety efforts are valued. It also helps in securing necessary resources, like equipment or protected time, often necessary for success. Senior leadership values the hands-on approach and frequently lists CUSP team successes as their proudest accomplishments.

The fifth step involves implementing improved teamwork and communication tools. For this module, we will discuss how the Learning From Defects process fosters teamwork and improves communication. It also produces localized tools that streamline processes, standardize care and improve patient outcomes.

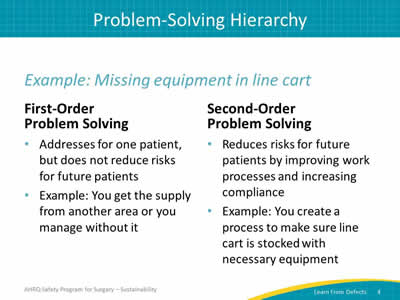

Slide 4: Problem-Solving Hierarchy

Say:

Let’s review a central piece of the Learning From Defects process. Learning From Defects involves understanding the problem-solving hierarchy. Problem solving breaks down into two types: first-order problem solving and second-order problem solving. Let’s walk through an example in which necessary equipment is missing from the line cart.

First-order problem solving is where we fix an immediate problem. If someone is in danger of injury or an emergent procedure is missing a vital resource, we do what needs to be done. We do what it takes to fix the situation for that patient, but do not develop a lasting solution.

It’s often viewed as heroic. In fact, such actions often are. Our culture sustains that belief. Our culture tends to reward first-order problem solving. Think about the kinds of events you see on the news, when people are hailed as heroes—dramatic rescues or interventions. These stories often describe first-order problem solvers.

While these actions are heroic and quick thinking should be rewarded, first-order problem solving fails to fix problems for the future. If you borrow from another room or department to help one patient, another patient will be at risk later due to the missing item. Additional first-order problem-solving exercises will soon be required to ensure the next patient gets what they need.

First-order problem solving is reactionary, rather than proactive. It doesn’t protect future patients or strengthen the system. The same problem, though addressed for that one moment in time, could easily happen again.

Ask:

What if the same situation occurred on a different shift?

Would every frontline provider solve the problem and save the patient?

Say:

Unless you fix the system and proactively prevent the defect from happening again, it will happen again. The risk must be eliminated for all patients.

After we congratulate each other on a great job with first-order problem solving, we must step back and ask ourselves some questions.

Ask:

What happened?

What can we do to prevent it from happening in the future?

Say:

This is the growth process from reactive first-order problem solving to proactive second-order problem solving. Each method has its place. Ultimately, we must develop system fixes that ensure every patient receives consistent and effective care.

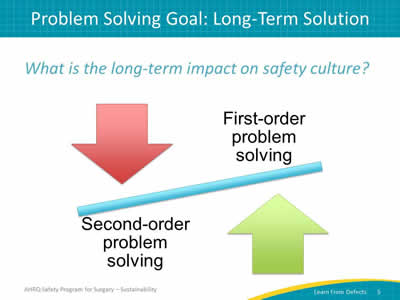

Slide 5: Problem Solving Goal: Long-Term Solution

Say:

As the safety culture advances, the need for first-order problem solving drops. With quality improvement in the preoperative, operating, and postoperative recovery areas, second-order problem solutions rise. The more systems-based interventions for local defects are implemented, the less likely clinicians will need to rescue a situation with first-order problem solving.

And you should find that staff recognize these system improvements. They recognize the intervention, and this is a great example of how you can see that seesaw shift from first-order problem solving to second-order problem solving.

Slide 6: What is a Defect?

Say:

What exactly is a defect? A defect is anything you do not want to happen or happen again. The Learning From Defects process can be very proactive. You don’t necessarily have to wait for a defect to surface. Use the simple two-question survey, the Staff Safety Assessment.

Ask:

How do you think the next patient will be harmed?

How will the next patient get a surgical site infection?

Say:

Encourage proactive thinking about the workflow in your clinical setting.

Ask:

How can we prevent this from happening?

Say:

When a defect has already occurred, ask your frontline staff. These incidences are well known to clinicians in the trenches. Ask them where the defects are. Ask them why these problems are occurring and where the problems reside.

Defects can be identified through a number of sources. The legal department has claims data; sentinel event data are also available.

The most impactful source of defects is your frontline staff through your surgical safety program process.

Ask:

What are the problems?

What might the solutions be?

Say:

Tap into the wisdom of your frontline staff and engage them in your surgical safety program efforts.

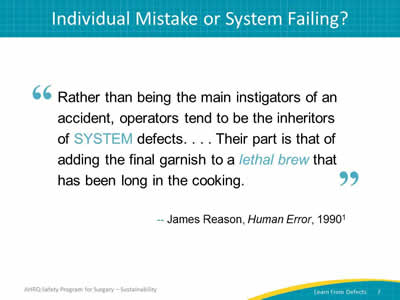

Slide 7: Individual Mistake or System Failure?

Say:

Is a defect an individual mistake or a system failing? As James Reason wrote more than two decades ago, “Rather than being the main instigators of an accident, operators tend to be the inheritors of systems defects…. Their part is that of adding the final garnish to a lethal brew that has long been in the cooking.”

To put it in more common terms, staff members get set up by the system. Clinicians come to work each day wanting to do things right, wanting to do things well. But barriers sometimes prevent us from doing what we know we should do in a timely, efficient, and safe manner. We wind up building workarounds to overcome poor system problems.

When workarounds or first-order problem solving are required, system defects are present. In the short run, you may prevent harm with first-order problem solving, but eventually individual events align, causing harm to a patient or staff member due to ignored system defects. Fundamental to the Learning From Defects process is stepping back and approaching how to fix problems on a deeper level.

You may have heard of ABCDs of medicine, otherwise known as the accuse, blame, criticize, and deny approach. Historically, health care manages errors along those lines. Once we can recognize the system limitations, we need to step back and say, “Look, it’s not an individual’s fault. It’s not Joe’s fault. It’s not Barbara’s fault. Joe and Barbara did the best they could.”

Your frontline providers are working within a system that both helps and hurts their efforts. You must step back and evaluate how these pieces interact.

Ask:

How do all these pieces lead to this error or the event that occurred?

Say:

Instead of just looking at individuals, we have to look across the entire spectrum. Learning From Defects requires a broad approach.

Slide 8: Learning From Defects: Sustaining your patient safety initiatives

Slide 9: Learning From Defects

Say:

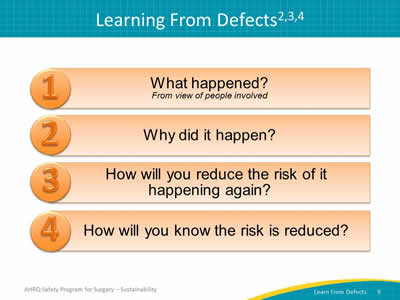

To review, Learning From Defects has four major questions. It sounds incredibly simple, and in some respects it is. However, the Learning From Defects process can surprise teams with how complicated it can become to drill down on defects.

The first question is, what happened? Find as much information and as many details as possible, especially from the perspective of the people involved.

Start asking why it happened.

Ask:

What elements interacted with each other?

Did anything mitigate harm and prevent it from being worse? Did anything else exacerbate it?

Say:

Really dig down and examine the incident in depth. This piece requires a lot of effort.

Ask:

How will you reduce the chances of it happening again?

Say:

Once you know what is going on, how can you prevent it from happening again? Dig into the literature to learn how others have faced similar defects. Approach your frontline staff for input on how to eliminate this situation. Whether your solution is evidence based or a creative local approach, apply what your team learns to your work area.

Finally, the last question identifies how you will know the risk is reduced. Patient safety and quality historically have often suffered from poor metrics. If you want to know whether the intervention to solve your defect is paying off, pay attention to question four and develop a way to measure whether the risk is reduced.

Slide 10: What Happened?

Ask:

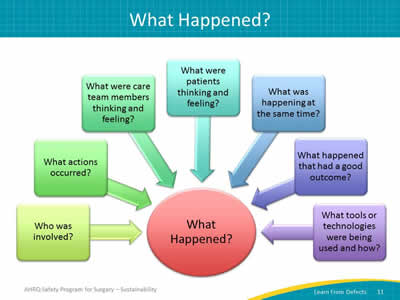

What happened?

Say:

We recommend walking the process. You remember the old adage: “Walk a mile in another person’s shoes.” Put your team into the situation, reconstruct the timeline, and reenact what happened. If you can, bring all the relevant participants together.

Bring them together. Remain nonjudgmental and non-accusatory. Make sure people feel safe to share openly; it must be an open environment where people can discuss what really happened.

If you can, simulate the defect, particularly for a defect that has occurred. Reenacting the defect serves as a powerful tool. Your team could recreate it as a tabletop exercise talking through the sequence of events.

Dig down into the reasoning and the emotions behind the actions and decisions. Were decisions made under pressure, despite distractions, or without appropriate knowledge of case or protocols? Again, encourage people to be open in a nonpunitive environment. That is essential to learning what is happening on the floor and to identifying the problems.

Take the time to listen. You need to understand rather than judge. Ask clarifying questions if you’re not sure.

Slide 11: What Happened?

Ask:

Who was involved?

What were the actions?

What were the care team members thinking and feeling at the time?

What were the patients going through at the time?

Say:

Often in patient safety and quality, we focus on the practitioners and forget to ask the patients. Where appropriate, go back and talk to a patient or a patient’s family. Their perspective will shed different light on the defect and provide a phenomenal patient-centered learning opportunity.

Ask:

What was happening at the same time?

Were there competing interests?

Were there distractions?

What else was going on?

What happened that actually may have helped ameliorate the situation?

Say:

Perhaps the event could have been much worse, except something went right. Don’t just focus on what went wrong; also focus on what went right.

Ask:

What kinds of tools or technologies did you have at the time?

Were the tools or technologies flawed?

Did they work well with the system?

Were there things you wish you had had that you didn’t?

Say:

Again, all these topics can be explored through the Learning From Defects process.

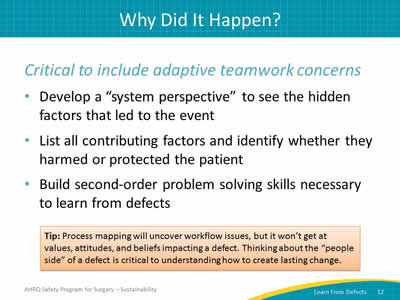

Slide 12: Why Did It Happen?

Ask:

Why did it happen?

Say:

Look for the hidden, latent factors that led to the event, not just the individuals who were performing those actions. You may notice technical factors as well as adaptive issues that contribute to the defect.

Documentation is important. List all of the contributing factors and identify whether they harmed or protected the patient. In virtually every situation, there are things that contributed and things that mitigated the event. Seek out and record both types of factors.

Intervene to correct factors that contributed to the event. Also, capitalize on any mitigating factors to create a more protective system for the patient. Build proactive second-order problem-solving skills into the process, and avoid the need for reactive first-order problem solving.

Slide 13: How Will You Reduce Risk of Recurrence?

Ask:

How are you going to reduce the risk of this defect happening again?

Say:

Armed with knowledge about what happened and why it happened, it’s time to build your interventions.

Ask:

What can we do to fix these problems?

Say:

Many small defects often contribute to big system flaws. Start by prioritizing the most important contributing factors. In order to develop an action plan, you need to prioritize your list of factors.

This part of the Learning From Defects process works well as a broad effort. While some teams prefer to prioritize which factors to address during the safety team meeting, other teams share the list for all frontline staff over an extended period of time. With this latter approach, consider posting an oversized list of factors in a common area on the unit, perhaps a conference room or a break room. Instruct staff members to vote (one way is with small dot stickers) for the factors most likely to cause harm.

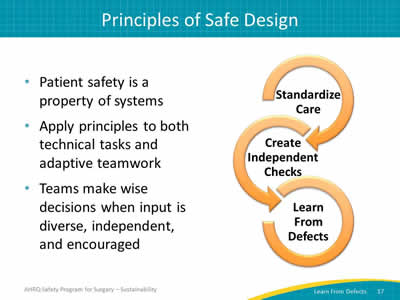

Keep in mind the principles of safe design:

- Standardize care.

- Create independent checks.

- Learn from defects.

Apply those safe design principles to both the technical tasks and the adaptive teamwork issues. In other words, employ safe design principles in terms of what you do and also how you do it. As a reminder, adaptive teamwork safe design principles examples are second checks, debriefs, and briefings. Technical tasks refer to the specific daily care checklists and protocols.

Slide 14: How Will You Reduce Risk of Recurrence?

Say:

Take advantage of your diverse team. Go back to your senior executive’s big-picture view of the organization and knowledge of and access to the resources. As you start tackling individual defects, you are going to need some resources.

Some tasks incur low or no costs, like creative improvements to the workflow. Other tasks may require some resources, such as protected time, new equipment, or computer programming expertise. Your senior executive can serve as a liaison to support project needs.

Defer to the expertise of your surgeons and the surgical team. By soliciting input from preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative staff including nurses, technicians, residents, and anesthesiologists, you are more likely to build sustainable interventions.

Evaluate the connections of your team members throughout your organization. Leverage those connections both into the wider organization and deeper into your own clinical area.

Tap into the wisdom of your frontline clinicians. They offer huge insight into defects and what causes or could cause the defect. Leverage everything at your disposal to improve patient safety.

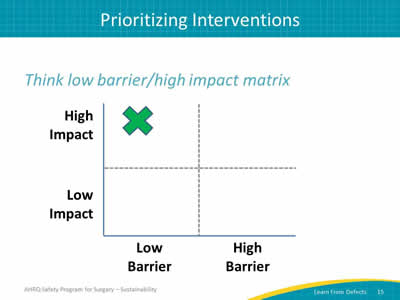

Slide 15: Prioritizing Interventions

Say:

Prioritize interventions that will have the highest impact and the lowest barrier. Don’t waste precious resources on hard-to-implement interventions unlikely to improve care. As a team, reflect on what you know are the barriers in your institution. Be realistic about the impact the interventions are likely to have. The intervention that applies to every patient will have more impact than the intervention that applies to two patients a year. Again, ideally you want high impact and low barriers for your first interventions.

If the literature indicates a particular intervention is a high-impact or a low-impact intervention, use that to help inform your process. In the absence of evidence-based recommendations, ask your frontline staff.

Ask:

What do they think?

Say:

As your team moves into sustainability, you have likely already experienced those early wins that build momentum. After your team has stretched its muscles, you may be ready to tackle a high impact but high barrier intervention.

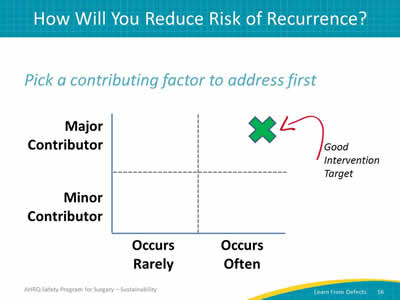

Slide 16: How Will You Reduce Risk of Recurrence?

Ask:

How will you reduce the chances of the risk recurring?

Say:

Your safe surgery team will need to prioritize its efforts. Pick a contributing factor your team would like to address first. Consider its impact on causing the defect, and whether the factor occurs rarely or has a likelihood of occurring again.

This grid provides a framework for prioritizing defects.

Ask:

Where would you place a contributing factor on the grid?

Say:

If a contributing factor is a major reason why the defect occurred, place that factor in the top row of the grid. For factors that occur often and impact a significant percentage of cases in your unit, place it in the column on the right. For example, the green “x” represents a contributing factor that occurs often and is a major reason why the defect occurred. This type of contributing factor is a good target for intervention.

Once your team has prioritized the contributing factors and compiled a list of solutions, consider rating them based on their ability to address the defect most directly as well as their feasibility. In other words, you will need to evaluate the amount of effort the solution will take and how much impact the solution will have on your patients.

For the team’s first defect, select a relatively easy to solve defect with the potential for a high impact on your patients. This type of solution is sometimes referred to as “low-hanging fruit.”

Those “low-hanging fruit” or “easy wins” are high-value targets that pay dividends. Not only will they be more successful and easier to sustain, but also they will build momentum on your team. For example, one hospital team elected to add push/pull signage to the doors in the operating rooms after a high volume of frontline staff complaints. The simple and inexpensive solution improved the working conditions and immediately doubled attendance at safety team meetings.

Early successes can engage your frontline staff, and ultimately, garner positive attention and professional respect.

Successful quality improvement teams get attention. When administrators discover that your surgical quality team is making waves in improving patient safety, it is a huge win. Early successes help you gain momentum in patient quality, but also at the administrative level in terms of resources that you will soon need in order to tackle bigger defects. Your team’s requests are more likely to be granted if you have a proven track record supported by data and the respect of your peers.

Slide 17: Principles of Safe Design

Say:

Earlier, we discussed applying the principles of safe design to the technical and adaptive pieces.

Keep in mind the principles of safe design:

- Standardize care.

- Create independent checks.

- Learn from defects.

Patient safety is a property of the system, not just individuals. So, if you can standardize care, you can improve care. By reducing variability, you will inherently improve consistent care delivery.

Independent checks are a fundamental component of safe design. They can be formal checks incorporated into the workflow, as well as informal checks where the care team speaks up when necessary.

Teams make wise decisions when input is diverse, independent, and encouraged by all members of the care team.

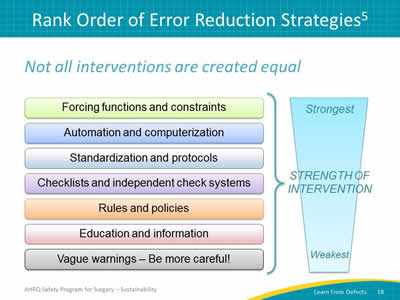

Slide 18: Rank Order of Error Reduction Strategies

Say:

Some interventions are stronger, or harder to ignore or override. Weak interventions are easier to bypass. As you build your interventions and you prioritize those with the biggest expected impact and the lowest barriers, keep also in mind their relative strength. For example,

Education and information sharing have wide variety in effectiveness. Sending an email blast will not be as effective as conducting a hands-on application of skills learning event with opportunities for questions and dialogue.

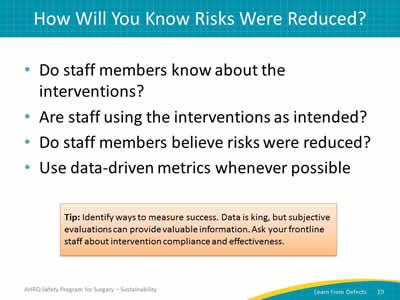

Slide 19: How Will You Know Risks Were Reduced?

Ask:

How are we going to know the risks are reduced?

Say:

This comes back to data and metrics. You need to know the numbers to drive your future quality efforts. Your stakeholders need to know that your area is reliable and efficient. Frontline clinicians want to know if their efforts are paying off. Senior leaders want to know their investments are yielding returns. Patients need to know if your hospital is safe.

People want to know the numbers. Public reporting and transparency are gaining momentum. Get ready. You need to have metrics.

Ask:

Does your staff know about the interventions?

Is the staff using the interventions as intended?

Does the staff believe the risks were reduced?

Say:

Again, use data-driven metrics wherever possible.

Use baseline data to help you determine whether you’re successful. The “after” picture is far more impactful with a “before” picture.

Make your data plans manageable and sustainable. To sustain, your data will need to support finding new defects, turning over defects, and getting them through the learning process.

One highly manageable way to build sustainable data plans is to audit. You do not need data on every single patient or in every single situation. Develop a sampling process where you periodically audit. For example, your team discovered an issue maintaining normothermia in the operating room. You don’t need to measure the body temperature of every patient every single day. Set up a schedule to periodically sample, perhaps a certain number of random cases each month.

Slide 20: Share Success Stories

Say:

Share your success stories. Summarize your findings and your changes over time. Brief your staff on the results of the staff attitudes questionnaires and HSOPS surveys. Share de-identified analysis of those surveys. Share updates on your initiatives.

Post prominently the results of the defects that you’re trying to reduce. When you advertise your efforts, you create a more open dialogue and develop a culture of safety. Make sure people see the successes; these are motivating.

Slide 21: What’s Next?

Say:

Sustainability is dependent upon ongoing safety assessment exercises.

Ask:

How do we achieve sustainability?

Say:

Once your team has completed a few cycles of the Learning From Defects process, you may be ready to work on several defects concurrently. Your defect pipeline will include some defects you are gearing up to tackle, others for which you are rolling through the process, and some you are wrapping up with solutions. An established surgical safety team will have at least one of these in each phase all the time. Interruptions to the cycle can easily wind down team progress. It is crucial to maintain sustainability and continue building on momentum.

Slide 22: Turnover Happens

Say:

Staff turnover is normal; it happens at all levels of the organization. Your team needs to prepare for it. Invite new team members as defects evolve. Cross-train team members to perform a variety of tasks. Rotate existing team members to perform different team roles.

It is important to have staff that can step in for data collection, meeting leader, or Staff Safety Assessment collection. Cultivate a depth of people with diverse experiences and exposures. Don’t let turnover derail your team or create inertia.

Slide 23: Key Takeaways

Say:

Let’s review a few main points from this module.

Focus on systems, not people. That’s central to the Learning From Defects Through Sensemaking process. People are not to blame. The system creates barriers that put people in situations in which they can’t do their job as well as they should, and sometimes patients are harmed. Instead, put your efforts into the individual factors that contribute to a system defect.

Prioritize the contributing factors and your interventions. Go for the low-hanging fruit to encourage early wins and build momentum. That momentum will help your team learn from more complex defects and garner resources to address them.

Use the principles of safe design in technical work and in teamwork. Go a mile deep and an inch wide—that is, spend time and energy investigating one problem deeply rather than multiple problems superficially. Learning From Defects is a close examination of a specific problem from the perspective of many stakeholders.

Learn from defects on a regular basis. Once you have mastered the steps of the process, aim to have at least one defect in each phase of the cycle: gearing up, rolling through, or wrapping up.

Ask your staff regularly what the defects are. New defects crop up all the time. It is remarkable how many defects develop in our complex health care system over time. New technologies, new techniques, new ideas raise new defects all the time. It is an ongoing process. If you are continuously tackling your defects, that is sustainability.

Slide 24: Action Plan

Say:

As you move into sustainability, review the Learning From Defects tool. Try to work through one defect from your operating rooms every month or every quarter.

Post the stories in which risks were reduced. Include data to show trends. Share with your frontline clinicians, department leadership, and interrelated departments. Share publicly or with your patients.

Your surgical safety team is not a short-term project team sprinting across the finish line. Quality improvement work models running a marathon, not a sprint. You can celebrate with high-fives along the way, but you continue moving towards improving patient outcomes.

Slide 25: References