Step 1: Establish Motivation and Interest of Practice

Literature on practice change and quality improvement8-10 has shown that successful projects share the following characteristics:

- The ability to establish practice champions (preferably, a physician champion for leadership and support and a project champion responsible for specific tasks and activities).

- The ability to capture the overall interest and "buy-in" of the majority of the practice (i.e., the entire care team).

- A focus on conditions that are of substantial interest to the practice (e.g., conditions that affect a majority of patients, cases that are problematic and frustrating, or topics that appeal to practice members on a personal level).

Establish a Project Champion

A project champion is "an individual who has the authority to use resources within or outside an organization for completion of a given project. A project champion is chosen by the management to ensure supervision of a specific project right from its initiation phase to its execution phase."11

As the individual reading this toolkit, you are more than likely the project champion. However, depending on the size of your practice, having more than one designated champion is optimal. If your practice is part of a system, it might be helpful to solicit a project champion from within administration that will support any extra time and effort you will put into this process.

As the project champion, you will likely take on the greatest responsibility in all steps of the project that occur outside the exam room and some of the steps inside the exam room as well. Your personal interest, passion, and commitment to the concept of connecting to community partners to improve patient care are critical to the success of the project. Your personal capacity and assessment of the practice's "adaptive reserve" (ability to absorb more projects and change) are also important.

Establish a Physician/Clinician Champion

The term physician champion is often used to describe a voluntary physician leadership role connected to a specific project or endeavor. While the physician champion of a quality improvement project could also be the financial and organizational lead of the practice, this is not necessary (and in some larger practices, not practical). The literature on physician champions equates the term with an opinion leader, a change agent, a physician who influences colleagues and friends.12,13 Think of EHR implementation—likely, a physician champion took on the role of promoting the cause and serving as the sounding board, advisor, and cheerleader to those in the practice. Very often, the physician champion can help the project manager solicit support from administration if the practice is part of a system. While a physician champion may not be responsible for the day-to-day implementation of the project, he or she provides the support needed for the project champion to make it happen.

Establish a "Learning Transfer" System for Your Practice

Typically, knowledge is transferred or disseminated two ways in a practice. The first method involves a central point of contact, usually the project champion, who works to bring general information about the community partner to all key players and clinicians in the practice. This person also encourages practice-wide adoption, and works with clinicians as they adapt the system to best fit their practice.

The second method involves a project champion who works closely with only one other physician/clinician, and together they determine the exact details for how the system should work within a single care team, unit, or pod within the practice. Depending on the success of the project, unique practice dynamics, and attitudes of other clinicians, the ensuing knowledge of "what works" within the single care unit or pod is then shared with others in the practice.

Often practice size, number of clinicians, ratio of clinicians to medical assistants/care team members, and overall organizational style will determine the best method for learning transfer. This often is not a decision the project champion would singlehandedly make, but a decision determined by the mechanics and style of the practice. Taking time upfront to pinpoint the learning transfer style and communicating the learning transfer method with the community partner will save time and confusion down the road, as the community partner works with a practice to assist in disseminating the information.

Respond to the Project Champion's Personal Questionnaire

As the project champion reading this toolkit, think through the questions in Tool 1 and write down the answers. (You can also share them with a potential physician champion.)

The exercise will help gauge your interest and energy level. If the effort seems overwhelming, this might not be the best time to embark on a new endeavor. Take the opportunity to ask yourself what kind of practice and patient activities would increase your professional satisfaction. This exercise will help you crystallize your own thoughts before you approach the rest of the practice. Don't worry if your primary population of interest is not patients with obesity; the majority of strategies in this toolkit should be applicable whether you are connecting with a YMCA or a support group for caretakers of patients with Alzheimer's disease. The key is picking a patient population that you are motivated to help through a QI project.

Gather Support

Next, you'll want to cement the support of the physician champion. If you are the physician champion, and you have the benefit of a having project champion for assistance, make sure your support of the project is visible to the entire practice; it can make a big difference in increasing the motivation of staff to put in extra time or effort.

If you are the project champion, ensure you have physician support before approaching staff. Physicians and clinicians should participate in a formal introductory-type meeting (Tool 2), as physician buy-in plays a critical role in staff buy-in.

Once the project champion and physician champion are identified, formally ascertain your practice's interest in embarking upon a QI project. Try setting aside 10 to 15 minutes in an all-hands staff meeting to share your thoughts and ideas. You can present the idea ahead of time, either through Email, in person, or both. A sample communication is shown in Tool 2.

Facilitate Staff Discussion

At the staff meeting, share the idea of partnering with a community resource, tell them about this toolkit, and then elicit responses on the questions below. An efficient method of collecting thoughts is to give everyone a sticky notepad and ask them to scribble down responses to the different questions—one thought per sticky note. If you are ambitious, you and an assistant can quickly categorize those post-it notes on the walls. However, just allowing staff to read off their post-its gives everyone a chance to talk and formalize their thoughts. Make sure to collect the notes at the end of the meeting.

- Do we think the idea of formally partnering with community resource is worth trying? Do you think the idea of formally partnering with community resources is worth trying?

- What do you know about community resources that could help our patients?

- Is it important to you? Is it worth doing? Are you willing to find the time for this?

- What are the possible benefits to our practice (e.g., QI projects that must be done anyway, increased satisfaction in patient care, etc.)?

- What would success look like?

Although these questions and answers seem obvious, being able to honestly and explicitly state the reasons for pursuing a practice project is an important step toward generating sufficient practice buy-in. To be successful, the majority of clinicians and their care teams should want to participate. However, full participation and buy-in can be challenging. With one willing clinician (it might be the physician champion), however, the project can move forward provided the clinician has adequate infrastructure and support (for example, a committed care team and support from the practice manager). Some practices find it helpful to be frank about who will and won't actively participate, with the understanding that some clinicians and care teams may choose to wait and see the progress of their coworkers.

Summarize and Cement Commitment

Consider keeping notes during the staff discussion and later summarizing and sharing the notes as a reminder as to why the project is important. This is where the sticky notes come in, as the notes can be summarized through an Email and later posted in a break room location that is readily observed, such as the refrigerator door. The sticky notes can also be displayed on a break room wall, perhaps organized into categories.

Documenting all-staff conversations can be difficult, but incredibly valuable. Tool 4 will help capitalize on the opportunity to preserve thoughts that can help generate future support and energy for the project.

Step 2: Find, Connect with, and Evaluate a Community Partner

Think of your search to find an appropriate community partner as akin to a patient searching for a new primary care physician. While the phone book or Internet is a good start, there are typically some parameters (insurance coverage, geography, etc.) that can help guide the process. Similar parameters exist for a primary care physician searching for an appropriate community partner. As discussed in Step 1, the community partner needs to offer services that appear valuable to the practice and the patients they want to target. As appealing as a community program focusing on children's safety might be, it might not be the most useful partner for a practice with a large geriatric population. Acknowledge your practice's limited time and energy, and look for a partner in which you'll receive the highest return on investment for your efforts.

Find a Partner

To find a partner, combine "asking around" with searching the Internet. Bring up the topic when speaking with coworkers, staff, personnel from other practices, friends, and so forth. Also, keep your ears tuned for useful community resources mentioned by patients. Then, use the Internet to search recommended or mentioned community resources. Conduct strategic Internet searches on local resources, and then ask your networking group for their opinions and personal experiences. Develop a list outlining your research (Tool 5).

Suggestions for an Internet search include:

- County health departments.

- State health departments.

- Programs offered by local hospitals (classes, wellness facilities, support groups, etc.).

- Local universities or colleges. (Type "community-based health" into the search finder to help locate the department that focuses on such services.)

- Health and wellness facilities, particularly nonprofit organizations such as the YMCA.

- Other nonprofit organizations such as TOPS (Taking Off Pounds Sensibly).

- Faith-based health programs.

Key words to use together or in combination during a search:

- Obesity (or the condition of interest).

- Your city/town/county.

- Community resources, organizations.

- Non-profit or nonprofit.

Reach out to individuals who may know of community resources:

- Health reporters for local newspapers, television stations, radio stations, Web sites, and blogs.

- Libraries, chambers of commerce, and city social services.

- Suggested resources listed for the Internet search (e.g., local colleges) may not offer a service but may know of places that do.

While nonprofit organizations are not the only ones that can offer services to your patients, they have the best chance of offering services at a reduced or sliding-scale fee that economically disadvantaged patients can afford.

Tool 5 can be easily converted into a spreadsheet with the suggested categories and others as needed. The goal is to take time upfront to put all the necessary information in one place.

If a physician or staff member has a high school or college-aged student who needs credit for doing a service project, having them develop this list could benefit both the student and your practice. The spreadsheet could then be housed on the practice's shared server. If the student has enough time, consider having them develop a hard copy notebook that includes the information from Tool 5, plus the brochures or printouts from the practice's or community resource's Web site. For both the electronic and hard copy versions, be sure to date each entry.

Connect to the Partner

The next step will be critical to establishing or deepening a relationship with a community partners/resource: setting a time to meet with the correct representative of the organization with whom you are looking to partner. It is likely that the resource has not been contacted by a primary care practice, so be clear and direct in what you are seeking. The template in Tool 6 can be modified for your practice and community.

Evaluate the Partner

The number of attempts it takes to speak to a knowledgeable person can be an important consideration in a potential partner's capacity to work with your practice to develop a productive working relationship. The potential partner's capacity to connect you to the right person, answer questions, promptly return Emails or phone calls, and send information should be considered. Like a medical practice, some community resources have the best intentions but become overwhelmed and struggle for time, money, or resources. Unless a partner is exceptional in its services and history, and your practice has enough capacity to carry the load, it would be wise to avoid any partnership with a community resource that seems perpetually short staffed and overloaded.

The AHRQ pilot project highlighted elements that practices might consider as they evaluate potential partners. When you make contact with the primary point of contact, consider asking the questions in the top part of Tool 7. The questions will help keep you on track, and the notes section that follows will help you make an objective evaluation about the organization's readiness and willingness to work with a medical practice. Tool 7 could be kept on the practice's shared drive.

When contacting the community resource, consider the experience from the patient's point of view. For example, is there one primary point of contact? Does he or she return calls and Emails promptly? What is the sense of organization and caring from the person on the other end of the line? Your practice is probably cautious about the specialists you refer patients to; referring to a community partner is no different.

Once initial contact has been made with a potential partner, a time should be set up to meet. The first meeting should be casual and, if possible, on neutral ground (e.g., a local coffee shop). At this point, you can further discuss the questions from Tool 7, and also use this toolkit as a basis for conversation. Remember that these steps are as important as establishing a referral system for sending patients to a cardiologist or other specialist. You and your practice need to feel good about the partner, enough so that you're willing to invest the extra time and energy into the project. If your time and your potential community partner's time are limited, you may need to skip to the second meeting.

The second meeting should be at your practice. It is critical that the potential partner gets a sense of how your practice operates in terms of workflow, patient path, intra- and interoffice communication, use of an EHR for referral purposes, and so on. Devoting an hour to giving the community partner representative a tour of your practice and making introductions will lay the foundation for a successful relationship in the future. It is important to have the representative meet the practice referral coordinator if your practice has one. Primary care is built on relationships, and the relationship with your community partner is no different. Linking a name to a face can make the difference in whether a staff member remembers to take 30 seconds to tell a patient about this new community partner.

Finally, the second meeting with the potential partner should reveal how receptive the organization is to working with your practice and the steps it needs to take to make the collaboration successful. If the representative is not interested in learning about your practice and the logistics of the referral process, this might not be the best partner for your patients. The time spent upfront will be worth the time saved on the backend.

During the AHRQ pilot project, the community partner representative visited each practice and spent half a day watching, observing, and chatting with practice members when appropriate. The community partner also underwent some "Primary Care 101" training with study team members to learn the typical jargon and lingo of medical offices, as well as general information about patient flow, work patterns, roles, and responsibilities. It might be helpful to direct your community partner to the following resources:

- This toolkit, so he or she can better understand what you are trying to accomplish.

- The YMCA toolkit for facilitators working with health care providers.

- The Community Based Organization and Health Care Professional Partnership Guide, toolkit from the National Initiative for Children's Healthcare Quality that guides advocates on how to link community based organizations with health care providers. Available at http://www.nichq.org.

Communicate With the Community Partner

After deciding to link with a community partner, the demanding and hectic schedule of the typical primary care practice can make regular contact challenging. Designating a project champion and sharing preferred contact information can help reduce the amount of missed phone calls, unread Emails, incomplete messages, and general confusion. Designating a clinician champion will increase the chances that everyone in the practice will help the project champion, and allow the community partner representative a clinical point of contact when needed. As elementary as it sounds, providing the community partner with the following basic information can help reduce frustration and mixed messages on all sides.

Project Champion—Communicate the following to your community partner:

- Best time to be contacted (days of week, time of day).

- Best method of contact (office phone, cell phone, Email, texts, in person).

- Current contact information (phone numbers, Email addresses, etc.).

- Backup contact person.

- Preferred methods of receiving information (Email, fax, mail, in person, combination)

Clinician Champion—Communicate the following to your community partner via the project champion:

- Any administrative or non-patient-care time the clinician may have and therefore be more available for a phone call or meeting.

- Current contact information (phone numbers, Email addresses, etc.).

- Preferred methods of receiving information (Email, fax, mail, in person, combination).

Tool 8 will take less than 5 minutes to complete. The community partner can use the same form to provide you with their contact information.

Most community partners that are willing to work with a primary care practice are willing to accommodate the practice however possible. As an example, the health facilitator in the AHRQ pilot project learned that Emailing information to practices to distribute to patients didn't work because there was a time and expense associated with printing, which the practices could not afford to incur. Also, the large volume of Emails that the practices received every day created a situation in which materials were getting lost—something mailed by the post office had a better chance of making it into the physician's inbox or being distributed at a staff meeting. Finally, the AHRQ pilot project was geographically suited so that the facilitator could make face-to-face visits with the practices and share materials.

What the health facilitator learned from this pilot is that while Email is almost always easier for the sender (the community partner), it can be difficult for the recipient (the medical practice). However, there is no way for the partner to know this unless the practice specifically tells them, and there is no detail too small when it comes to establishing successful communication.

Step 3: Identify Patients

The identification of eligible patients is two-fold: first, does the patient fit the physiological profile of someone who may benefit from the community resource; and second, does the patient demonstrate a minimal level of "readiness to change?" In the AHRQ pilot project, practices had to identify patients who met the physiological requirements for the YMCA Diabetes Prevention Program (i.e., prediabetes by either a blood test or other risk value). Not surprisingly, identifying these patients by physiological measurements was fairly straightforward. However, both the study team and practices learned that physical eligibility alone was insufficient for prompting a patient to take the next step and acting on the referral. Assessing the patients' readiness to change will be addressed in "Chapter 4. Linking with the Patient," which includes patient engagement tools. In the AHRQ pilot project, practices had two distinct methods of targeting their patients (preemptive and point of care), and at times these methods were used interchangeably or simultaneously.

Preemptive Identification

Some practices in the AHRQ pilot project took a "wide net" approach by searching all possible patients who might be physiologically eligible for the YMCA's Diabetes Prevention Program (YDPP). Knowing the close association of elevated blood glucose with obesity, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia, practices used a combination of ICD-9 codes to query their EHRs to find eligible patients. In this particular pilot project, elevated blood glucose was a prerequisite to participate in the YDPP; however, many obesity management community programs exist that do not have such stipulations. (In such a case, querying by body mass index (BMI) or the ICD-9 code for unspecified obesity would likely work.) Once the patients were identified in the AHRQ pilot project, the practices used a variety of methods, specific to their work environment and EHR, to flag eligible patients. One practice was able to use a "pop-up" reminder within its EHR (e.g., "consider referral to the YDPP") for each identified patient. Other practices simply highlighted the information within the record. Go to Tool 9 for examples on how to query patients.

Once patients are queried, your practice can choose the best way to build a registry for tracking, either through your EHR or a stand-alone registry with a spreadsheet. Developing a registry is not the most critical step in developing a partnership with a community resource, so lacking the time or resources to do so should not impede work with a community partner. However, building a simple but formal registry for the patients you intend to refer will likely pay off with the enhanced ability to track patients and generate reports, as well as the incentives provided by many health care plans and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). The steps to building a useable database are beyond the scope of this guidebook, but many excellent sources are available for free, including an article and brief toolkit from the American Academy of Family Physicians.14

Preemptive Identification Advantages. Casting a wide net allows a practice to review the entire spectrum of patients, including those who are overdue for a visit. The patient-centered medical home movement encourages practices to take a proactive population-based approach to patient care, and this strategy fits well within those domains and the requirements by some recognition organizations such as the National Committee on Quality Assurance (NCQA). The provision of self-care and community support is among NCQA's six standards for the 2011 recognition program for the patient-centered medical home. (More information is available at www.ncqa.org.)

Most practices have probably conducted a quality improvement project that requires the identification of a certain population of patients (e.g., patients due for a mammogram) and, thus, previous strategies can be adapted for identifying patients considered clinically overweight or obese.

This also allows clinicians to review patient lists ahead of time to identify which patients might be the best candidates for referral. This strategy affords the practice the opportunity to proactively reach out to identified patients with a phone call, Email, letter, or other method of communication. One clinician in the AHRQ pilot project sent a letter to identified patients asking them to consider the YDPP and encouraged them to schedule an office visit to discuss the program in regards to their health.

Preemptive Identification Disadvantages. Not having an EHR and having to manually review patient charts could be considered a preemptive identification disadvantage. All the practices in the AHRQ pilot project that used preemptive identification had the benefit of an EHR. One practice implemented an EHR midway through the project, and it was only then that they could query for patients. Practices without EHRs could build a simple tracking database, but this would require the manual review of all patient charts to find the appropriate patients—time consuming, but not impossible.

Compiling patient names is just the first step. Additional time and resources will be needed to take the necessary steps to turn the patient list into actual referrals and then enrollment into the program. These steps need to be factored into the overall quality improvement project, which can make it seem more daunting.

There is a fundamental difference between identifying a patient by physiological criteria and making a referral, and identifying a patient by both physiological and "readiness to change" criteria and then making the referral. The AHRQ pilot project demonstrated that compiling a list and making referrals does not guarantee patients will act on that referral.

Preemptive Identification Case Study. One clinician and her care team in the AHRQ pilot project queried their EHR system to generate a list of patients who qualified for the YDPP (using ICD-9 codes for abnormal blood glucose). Next, they worked with their community partner (in this case, the YMCA) to create a simple letter that included information about the YDPP and the contact information. The letter also invited patients to schedule a visit with their clinician to talk about their health and why the YDPP might be a good choice to consider. This preemptive approach produced a list of several hundred patients, many of whom did schedule a follow-up visit after receiving the letter and were subsequently referred to the YDPP. Go to Tool 10 for a sample letter.

Point-of-Care Identification

Some practices in the AHRQ pilot project adopted the approach of identifying a patient as a good candidate either directly before or during the patient encounter. In this scenario, the clinician or ancillary care staff (e.g., a certified diabetes educator) would note that the patient was eligible for the YDPP through both their physiological markers and their attitude towards making lifestyle changes. Patients would be approached individually and specifically selected for the referral "invitation," and the clinician would build upon past positive conversations and the existing relationship to make the case for lifestyle change. One physician described the trigger for the referral conversation as a "feeling" he had that this was the right time to bring up the topic.

Point-of-Care Identification Advantages. In practices where clinicians work in complete autonomy, it might be difficult or even impossible to initiate a practice-wide patient query. Point-of-care identification allows a single clinician to work independently (or with a key staff member) and still see success with his or her own patients.

This method also allows clinicians to embrace the "art" of medicine; instead of working from a list, they are using their intuition and patient relationships to make decisions about the

Although this physician did not refer many patients, the patients he did refer had the highest enrollment rates. This physician also relied upon motivational interviewing strategies with patients, some of which will be shared later in this toolkit.

Hybrid Approach

It is expected that most practices will choose a hybrid approach of the preemptive and point-of-care identification techniques. One approach does not preclude another, and practices are encouraged to consider the advantages and disadvantages of both and reflect upon their own work environment. The following questions may provide some direction:

- Practice buy-in: How many clinicians would be willing to participate? Will this be a practice-wide effort or confined to just one clinician and care team?

- EHR: How accommodating would our current EHR be in our efforts to query patients and/or build a registry? How much help could we expect to get from the EHR vendor?

- Patient outreach: Do we have an established way of reaching patients outside the office (e.g., Email, Web site, letters, etc.)? How much time, energy, and resources would it take to develop a method suitable for this endeavor?

- Similar QI projects: Has our practice conducted other quality improvement projects similar to this one, so we can repeat and reuse query requests, patient outreach methods, etc.? Or, would we be starting completely from scratch?

- Clinician passion: Is the physician champion heavily invested and committed to the success of the program, enough so to remember to self-identify appropriate patients and initiate a referral?

Hybrid Approach Case Study. One practice in the AHRQ pilot project had a highly functioning EHR that generated pages of lists of eligible patients for the community project. Several of the clinicians followed the lists and liberally used the referral forms. However, a feedback report provided by the community partner highlighted a conversion rate of only about 1:15—of every 15 patients referred, only one actually enrolled.

While acknowledging the power in numbers, the clinical care coordinator also realized that perhaps the clinicians needed to enhance the way they talked to patients about the referral process. She worked with the community provider to coordinate a brief training session on motivational interviewing as part of a regular monthly meeting. The practice still intends to cast a wide net by using EHR queries, but the motivational interview training has helped the clinicians target their time and energy into patients most receptive to change.

Step 4: Create and Use a Referral Form

A long, complicated referral form will either sit in a cabinet drawer and collect dust or reside, incomplete, within an EHR. Thus, it is helpful to take the time upfront to figure out the exact details that the community partner needs in order to initiate contact with the patient, and include nothing more. For the AHRQ pilot project, a set of clinicians provided feedback about what information they could reasonably document in a referral form during a typical patient encounter. The YMCA Diabetes Prevention Program representative was able to use their input to create a referral form that also gave her the information she needed; that is, was this patient eligible for the program, or did she need to conduct a more complete assessment? From this collaborative exercise, the following questions emerged:

- What is the perfect marriage of information the community partner needs to initiate contact and information only a clinician can provide? For example, there is no reason for the clinician to fill out the patient's address; the community partner representative can complete that part over the phone with referral patients. However, only the clinician can check whether or not a patient's blood work indicates a certain condition.

- If the practice still uses paper, what is the preferred physical format of the referral form? The AHRQ pilot project found most clinicians preferred a full sheet of paper, as it was easier to scan and/or slip into a medical chart. Even some "paperless" practices using an EHR for referrals still liked having the visual trigger of the paper format, and the ability to hand the form to the patient once the referral went through the EHR.

- Who will fill out the referral form and at what point during the patient encounter? (e.g., physician, medical assistant, referral coordinator, etc.?) In one practice, scanning the list of the day's patients gave the physician the opportunity to identify possible referral patients; then, the physician asked the medical assistant to partially fill out the referral form ahead of time.

- How will the referral form be entered and passed through the system; and how will this referral be documented in the patient's chart? (e.g., typed directly into the EHR, customize a drop-down referral screen, scan a paper form, etc.?) Some practices in the AHRQ pilot project were able to integrate the referral form into the EHR, allowing a simultaneous process of referral and documentation. Other practices electronically faxed the referral form, but still had to make separate notes in patient charts. Finally, others chose to save up the batches of forms to hand deliver to the community representative when she came to visit; those referrals also had to be noted separately in the patient chart, usually with inclusion of a scanned referral form.

- What are some of the HIPAA-compliant considerations? The practices participating in the AHRQ pilot project were fortunate in that the community partner, the YMCA, used a secure electronic fax system, and all individuals with access to the system underwent HIPAA training. Not every community partner will offer that degree of protection, so the referral form used should reflect this (i.e., only using the phone or regular fax to refer or not including any personal health information on the referral form). While there is no one-size-fits-all approach for computer security, an article by the American Academy of Family Physicians, "10 Steps to HIPPA Compliance," offers practical steps to consider.15

Case Studies. Several practices in the AHRQ pilot project used a designated referral coordinator to manage the referral process. This individual was asked to integrate the community-resource program referral process into the system just as they would for a referral to a medical specialist or to ancillary care, such as physical therapy. The following elements seemed to markedly increase the success of the referral system and coordinator.

- The commitment level of the referral coordinator and his/her personal belief in the value of the community program. In one practice, referrals were lagging until an unhappy employee left the practice. When the position was filled by someone excited and enthusiastic about the process, the referral numbers started to climb. This individual even took the initiative to send an Email reminder to the clinicians every few weeks, reminding them to refer patients when appropriate.

- The technical ability to include the community program into a referral menu within the EHR, allowing a seamless transfer of information while simultaneously documenting the referral, and possibly triggering an automatic electronic "tickler" to follow up.

- If the EHR does not facilitate community referrals, the ability and tenacity to establish a stand-alone simple tracking system. Some practices in the AHRQ pilot project struggled with EHRs that did not allow customization of the drop-down referral box, making the process more difficult because the referral coordinator now had the extra step of external documentation. However, one referral coordinator developed a simple spreadsheet that tracked each patient, including the date of referral, the coordinator's follow-up efforts to contact the patient, and any information received back from the community program.

- The ability and tenacity of the referral coordinator to personally follow up with referred patients. This impresses on the patient the importance of the referral to the clinician and the practice. While the ability to leave messages varied by practice in the AHRQ pilot project, the coordinator would use a script similar to this: "Hello, this is ______ from Dr. ______'s office. I'm just calling to check up on your referral to the YMCA Diabetes Prevention Program. Dr. _____ really felt this program would be a good fit for you and wanted to make sure you were able to talk to them and get your questions answered. If you have any questions for Dr. _____ or for me, please call this number. I'm here from 9 am to 5 pm every day and coordinate all the referrals."

Note: Appendix A (Case Studies) in this toolkit describes some of the practices in the AHRQ pilot project in more detail. Of the practices, A, B, and D used a designated referral/chronic care coordinator. This individual was already doing another fulltime job, so she or he worked with the community partner to determine the best way to track referrals without adding extra work.

Step 5: Integrate the Process Within Patient Paths

Based on the experience of the AHRQ pilot project practices and the general evidence base currently available, establishing a successful referral system requires two complementary components: a committed physician/clinician champion who works to connect to the patient inside the exam room, and enough practice team members willing to reinforce that message at appropriate moments outside the exam room. The former component will be addressed in the second part of this toolkit; the latter component, however, can be addressed through a simple patient path exercise.

As part of the patient path exercise, conduct a physical walk-through the practice (perhaps using the community partner representative as a fresh set of eyes); use a large piece of paper taped to the wall during a staff or stakeholder meeting to diagram the patient path; or employ the tool that accompanies this toolkit. Whether physically or on paper, start by walking through your practice.

Initial Contact and Outreach

Before your patients even walk through the front door, how do they communicate with your practice, and can that source of communication promote weight management resources within the community?

Example: A practice Web site could provide links to community resources such as to the YMCA or TOPS (Taking Off Pounds Sensibly); a clinician could provide an extra word of endorsement on the Web site; or a clinician, staff member, or patient could post their own weight loss success stories.

Waiting Room

What literature and reading materials are available in your waiting room? Will your patients feel like your practice promotes wellness and healthy lifestyle changes? Most community resources will be happy to provide brochures, but think beyond brochures and ask the community partner to provide a full-size poster for an easel, to take ownership of a bulletin board, or to provide a scrapbook of success stories (with participant permission).

Example: Patient or staff testimonials can be very powerful. One of the most successful strategies in another healthy office research project used waiting room posters to highlight staff members who had lost weight. Many patients turned to these staff as role models.

Vital Signs and Weight Stations

Most practices have a scale in a specific area. Consider putting community resource signs or a BMI poster above the scale. This may help trigger a positive conversation about weight management during the weight measurement.

Example: Visual cues can be helpful to both patients and medical staff for different reasons. An appropriate sign could prompt the patient to start a conversation about their weight, and the medical assistant could either address the patient's concerns or make a note to the clinician to follow up. Likewise, the visual cue could help busy staff remember to focus on a specific component of the visit, such as making sure every patient understands the meaning of BMI.

Exam Room

Patients often spend more time in the exam room than in the waiting room, but with less access to reading material. Consider how a motivated community partner could use that opportunity to promote not only their program, but also healthy lifestyle choices in general with brochures, posters, and scrapbooks. A practice could also provide its own laminated list of community resources for obesity management—simply put the list on the exam room chair or table.

Example: Many practices now belong to health care systems with rules about posting anything beyond approved art or diplomas on exam room walls. One practice in the AHRQ pilot project received permission to put YMCA Diabetes Prevention Program posters on the backs of the exam room doors, which the clinicians said was effective in serving as a visual cue.

Other Opportunities for Visual Cues

Many practices have limited abilities to use exam room walls for promotional and visual cues. One clinician in the AHRQ pilot project got around this by simply placing the community brochure in a manila folder with other paperwork he intended to review for every patient. He explained that seeing the brochure several times a day helped him remember to talk to appropriate patients.

Example: Are there other areas, besides the exam room, where the patient might be sitting as a "captive audience?" Examples include the patient restroom, a screen saver on the computer in the exam room, or in the blood draw waiting area. Urge all interested clinicians to think about what kind of subtle visual cues might work best for them.

EHR

With the understanding that some practice staff already suffer from "reminder fatigue," consider feasible ways in which the EHR could be employed as a visual reminder (e.g., pop-up reminder box, question or statement added to the interview) or interactive tool (e.g., part of the patient's health risk assessment). The AHRQ pilot project revealed that several practices actually preferred poster or brochure cues, citing that the EHR was constantly changing. However, some practices did find ways to make the EHR part of the process.

Example: One practice in the AHRQ pilot project customized its EHR by adding a pop-up reminder for patients who met the criteria for the community resource. The reminder linked directly to the referral card, which was then electronically faxed to the resource. Two other practices added the community resource directly into their drop-down referral checkbox.

Nonpatient Areas

Although it sounds counter intuitive, do not limit the patient path to the areas where the patient physically moves. Where do staff and clinicians reside between patients, and how might that space be optimized for reminders? For example, if clinicians still receive some lab results via fax, a sign above the fax machine promoting a community program for prediabetes or diabetes might be a timely trigger. Also, consider the staff break room, kitchen, and individual phone and computer stations as locations for community program materials.

Example: The community representative in the AHRQ pilot project provided resistance bands to some practices along with a printout demonstrating several stretching exercises. Staff could do some of the exercises at their phone stations, which not only improved their wellbeing but kept the community partner at the forefront of their mind.

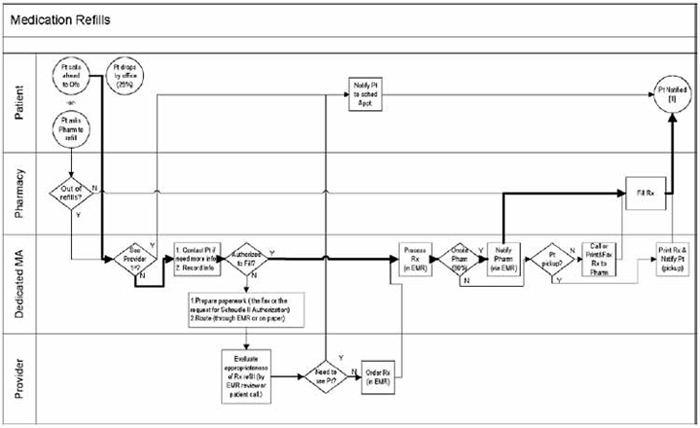

Process Mapping Resources. Some practices will find that a simple walkthrough is adequate for this process, and tips on maximizing the experience can be found in an article, "How to See Your Practice Through Your Patient's Eyes" (www.aafp.org/fpm/2008/0600/p18.html).16 Other practices might find that taking a more formal approach by way of "process mapping" can be useful, particularly in larger practices or those with additional resources to help with continuous quality improvement efforts. Process mapping has its roots in industrial engineering as a way to help manufacturers reduce waste and optimize efforts. It has since become a tool for virtually all kinds of companies and businesses, including medical practices, as a way to objectively view workflow and realize opportunities for improvement. The Improving Efficiency in Primary Care toolkit (http://fammed.ucdenver.edu/efficiency/default.htm), provides a detailed example of a process map for prescription refills (go to Figure 1 for example).

Tool 11 is intended to combine the best of the practice walk-through and the process map. Consider filling it out as part of an all-staff meeting or a one-on-one discussion with other project stakeholders. The template can be printed out and distributed among the care team.

The rectangles represent each activity in which a casual mention or formal referral of the targeted community partner could be initiated (e.g., at the weigh-in portion of the patient encounter, during the family history portion of the exam, during medication reconciliation, during a phone call to report recent lab results). The level of detail can be personalized by your practice and the person responsible for completing the map. You may want to break out the activities on the map based on the different members of the care team, or you may choose to organize the map by activities within a patient encounter inside the exam room. The template is intended to be generic enough to allow customization.

The circles above the rectangles represent the referral actions that accompany the original activity. For example, if a clinician reviews a patient chart during the morning huddle, the huddle would be indicated in the rectangle and the circle would represent the medical assistant flagging the chart to remind the clinician that the patient is a good candidate for a community referral. You might find that some of the tools or activities incorporated into the second part of this toolkit focusing on patient engagement also fit into the process map.

Finally, the cylinders below the rectangles are intended to serve as a checklist for needed tools, resources, or follow-up steps.

Step 6: Develop a Feedback System

A bidirectional referral process only works if the community partner knows what kind of information would be helpful to the practice, as well as how and to whom to send the information. Be very explicit in communicating to the community partner the importance of data and feedback. Chances are the partners will assume the patient is keeping the clinician up to date, and will want to avoid sending duplicate information. Provided your practice wants to receive regular and timely feedback, you might ask the community partner to provide your practice with regular reports that answer the following questions:

- Were you able to make contact with the patient? If contact was made, did the patient enroll in the program, or did the patient decline entry?

- If the patient did enroll, did your program collect baseline and ongoing data that you can share as the program progresses (e.g., weight or attendance in class)?

- If the patient declined enrollment, can you share their reason?

- Can you send the information back to our practice using our preferred format (e.g., electronic fax)? (Note: the practice will need to specify the preferred format; do not assume the partner will know this. Also, specify the best person to receive the reports to ensure they get to the right clinicians.)

It should be noted that once a patient joins a program, the community partner might be limited on how much information they can share without the patient's permission. Some programs ask the patient to sign a form that allows the instructor to send attendance or biometric data to their clinician. In the AHRQ pilot project, at least one patient did not want their physician to know they were in the YMCA Diabetes Prevention Program because they wanted to surprise the physician after they lost weight.

Once you have determined what type of information the community partner is able to provide, decide on the best ways to receive that information. Issues to consider:

- Should the feedback reports come back via fax, Email, postal mail, etc?

- Who should receive the reports, and who should be responsible for sharing the information with the rest of the practice, especially the clinicians?

- If the feedback report goes directly into a patient chart, how will the clinician be alerted that the information is there?

- If the information is delivered in a way that requires entry into an EHR (data entry or scan), who will be responsible for doing so?

Case Studies

For the AHRQ pilot project, the YMCA health facilitator employed two types of reports to keep the practices notified of patient referral activity: enrollment reports and specific patient followup reports.

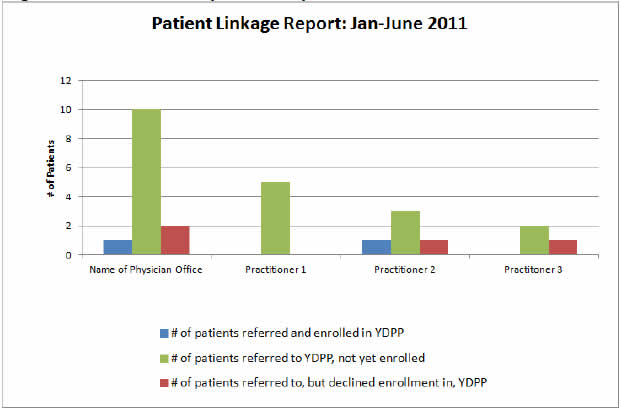

Enrollment reports. Originally it was thought that practices would only be interested in how many patients they had referred to the YMCA Diabetes Prevention Program, and how many of these patients converted to enrollments. The facilitator used a type of customer relationship management (CRM) software to create quarterly feedback reports and Emailed the reports (no patient names, number of patients only) to the practices. In some cases, the reports didn't reach the right individual, which is why this toolkit encourages explicit designation of a point of contact. However, when the charts reached the right individual, they were displayed on a break room wall, which helped increase overall awareness of the project and fostered healthy competition.

Even if your community partner is unable to create colorful reports as in Figure 2, consider ways the information can be easily shared with the entire practice. Although Email is fast, consider the impact of printing and posting the data in a place that is well populated.

Specific Patient Follow-up Reports. In the AHRQ pilot project, it was a surprise to the community health facilitator how much the clinicians wanted follow-up information on the patients, especially when the patients did not respond to the referral or declined participation. As one clinician explained, "If I referred my patient, and they come back to see me in 2 weeks for another problem, I would like to know if they actually acted on that referral. If they joined the class, I want to congratulate and encourage them. If they didn't, maybe I can find out why and suggest something else. Being able to follow up increases any possible impact I can have." Based on that feedback, the health facilitator created follow-up patient reports to fax to the practice every month. Again, it was critical to determine a primary point of contact that made sure the correct physician received the correct patient data. Do not assume the community partner knows the type of information that is helpful. Be specific and then follow up to make sure there is a functioning communications trail.