Action Plan for Translating Research Into Practice: Gap Analysis and Tests of Change: Facilitator Guide

AHRQ Safety Program for Mechanically Ventilated Patients

Slide 1: Action Plan for Translating Research Into Practice: Gap Analysis and Tests of Change

Say:

This module will cover the Translating Research Into Practice (TRIP) framework. The TRIP framework lets us dig deeper into implementing the evidence-based interventions. We will also discuss gap analysis and test of change.

Slide 2: Learning Objectives

Say:

After this module, you will be able to list the steps of the TRIP framework. You will be able to define gap analysis and list the principles of test of change. You will be prepared to pilot a test of change and collect data to evaluate a potential intervention in your setting.

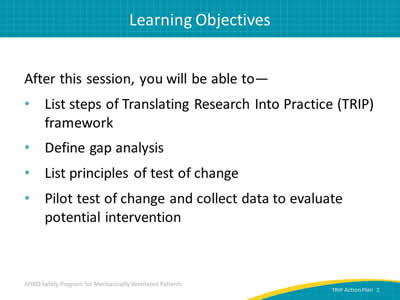

Slide 3: Model for Improving Care

Say:

Quality improvement work in health care requires multiple components to address the problems specific to a local unit and the global issues that impact particular care service lines or patient populations. These individual components integrate improvement initiatives to create the necessary synergy to improve care and patient outcomes.

First, local problems are addressed with the Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program, or CUSP. Local units measure the clinician and staff perceptions of safety culture, such as the Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture. CUSP includes regularly educating staff on the science of safety and then identifying defects in the delivery of consistent and evidence-based care. CUSP teams partner with a senior executive to solve complex issues that require resources or interdepartmental collaboration.

Ultimately, CUSP teams solve defects and improve the communication among team members and increase the safety culture on the unit. This work is often called adaptive, as it pertains to teamwork and staff attitudes that impact their clinical tasks. These adaptive challenges are often the more difficult obstacles a safety team will face.

Next, safety teams must integrate evidence into technical workflow. Translating Evidence Into Practice, or TRIP, is a framework for synthesizing evidence-based care practices into actionable procedures. The TRIP framework first summarizes evidence in a checklist. After local barriers to implementation are identified, baseline performance is measured. The 4Es model ensures that all patients receive evidence-based care through engagement, education, execution and evaluation phases.

The next column is specific to the evidence-based technical interventions your safety team will implement. This safety program is designed to improve care for mechanically ventilated patients. It includes technical interventions such as elevating the head of the bed by 30 degrees, minimizing sedation, and performing awakening and breathing trials.

CUSP and TRIP work together to integrate technical and adaptive improvement initiatives to create the necessary synergy to improve care and patient outcomes.

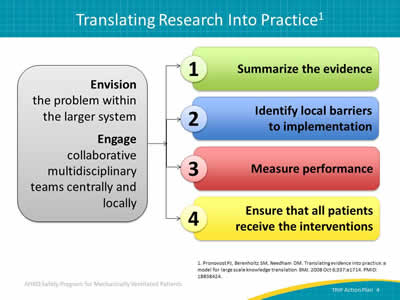

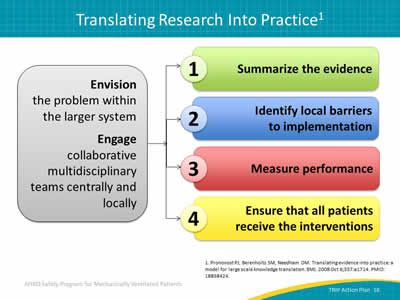

Slide 4: Translating Research Into Practice

Say:

The TRIP framework focuses on solving a problem within your system. Envision the problem with the larger system and engage multidisciplinary teams to collaborate on how to address the problem. Too often departments work independently without exploring the downstream effects. Effective change of practice requires collaboration of multiple roles and departments.

First, summarize the evidence supporting your intervention (future modules will provide evidence on the interventions in this safety program). The second step is to identify any local barriers to implementing your intervention. Third, measure your performance. Finally, step four is to ensure all patients receive the interventions.

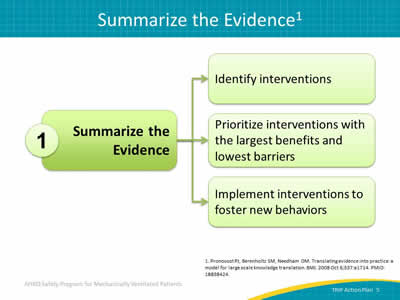

Slide 5: Summarize the Evidence

Say:

To summarize the evidence, first identify the interventions you plan to implement in your unit or hospital. For example, right now we are talking about a safety program that includes daily care process interventions, such as elevating the head of the bed at least 30 degrees and using subglottic secretion drainage endotracheal tubes for patients expected to be intubated more than 72 hours. Interventions also include tailoring mobilization goals to each individual patient to maximize early mobility, as well as minimizing sedation.

Next, prioritize the interventions with the largest benefit and lowest barriers. Your team might focus on the daily process interventions before implementing early mobility interventions. Patient mobility depends on patients being awake and alert. A significant barrier to mobilizing patients occurs when patients are under sedation. By first minimizing sedation and then employing spontaneous awakening trials, your team will be more prepared to address mobilizing patients.

Last, define and implement interventions that will foster those new behaviors.

The technical interventions discussed in this guide are supported by evidence-based interventions. We will discuss all of the technical interventions used in this safety program in greater detail in later modules.

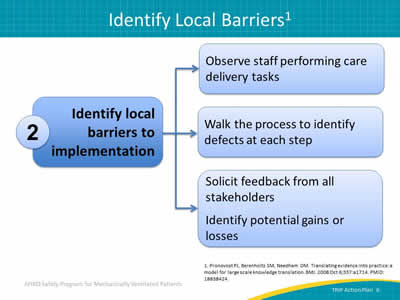

Slide 6: Identify Local Barriers

Say:

The second and most important step of the TRIP framework identifies local barriers to implementation. Observe the practice of frontline staff performing daily tasks. Walk the current care delivery process to identify defects at each step. You want to identify the current practice and proactively solicit information on what might hamper procedure changes.

Ask:

What is the current practice related to sedation?

What’s the current practice related to mobility?

What’s your current practice in weaning patients?

Say:

To answer these questions, you need to visualize what’s going on in your unit and get feedback from frontline providers. For example, suppose your unit has low compliance rates on a specific care measure, like spontaneous breathing trials. Ask why. The answers to those questions will help you identify local barriers.

Ask:

Why weren’t the spontaneous breathing trials performed as expected? (The patient was sedated.)

Why was the patient sedated? (Perhaps no order was given to halt sedation. No assessment was performed to indicate the patient needed lighter sedation.)

Say:

Solicit feedback from all stakeholders, such as the charge nurse, unit nurses, respiratory therapists, residents, and attending physicians. Identify the potential gains or losses in current practice.

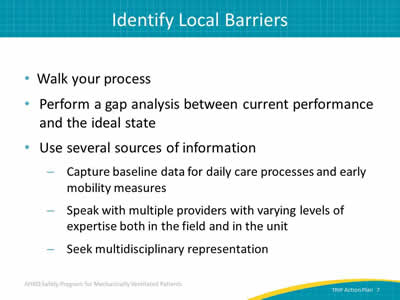

Slide 7: Identify Local Barriers

Say:

To reiterate, to identify local barriers you must walk your process. At this point you can begin to perform a gap analysis. A gap analysis involves looking at the difference between your current performance and the ideal state.

You will want to collect information from multiple sources. This program outlines many process and outcome measures. Collect baseline data on your daily care, early mobility, and/or low tidal volume ventilation process measures. This provides a quantifiable starting point to evaluate progress of your safety program progress.

Speak with multiple providers with varying levels of expertise both in the field and in the unit. Be sure to include representatives from all relevant disciplines, like pharmacists, respiratory therapists, and physical therapists.

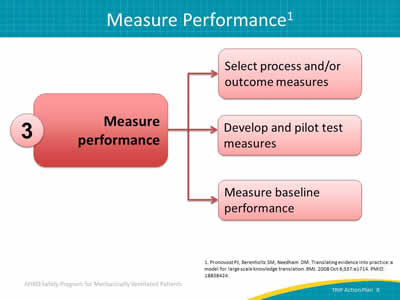

Slide 8: Measure Performance

Say:

Next you will need to identify how you will measure performance. Select the process and outcome measures most relevant to this work. Process measures are measures of the performance of standard procedures of care delivery for interventions you are implementing. Examples include performance of spontaneous awakening and breathing trials. Outcome measures are high-level clinical or financial results that concern health care organizations. Examples include mortality rates, length of stay, and rate of ventilator associated-events.

Next, develop and pilot test measures. We will talk more about piloting tests of change later in this module. You will need to measure baseline performance. Data drives all quality improvement work, particularly data clinicians find valid. Baseline performance data will support your efforts to implement changes and track local progress.

Slide 9: Measure Performance

Say:

In summary, identify metrics that will quantify the current practice, and track progress over time. Collect baseline data on the current practice.

Then identify your desired state.

Ask:

For this initiative, what do we want to see?

Say:

We want to see alert patients getting off the ventilator quickly. We want to see patients sitting on the edge of their bed or ambulating in the hall.

Share this vision with your team. You may need to tweak your vision as new evidence emerges. Successful implementation efforts will include a vision shared by each member of your clinical setting.

Slide 10: GAP Analysis

Say:

We mentioned gap analysis earlier. Let’s dig a little deeper on this topic.

Slide 11: GAP Analysis

Say:

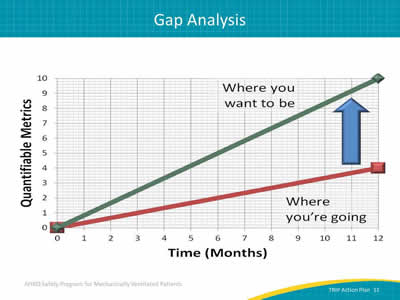

As a reminder, gap analysis is defining the difference between your current performance, or where you are now, and the ideal state, or where you want to be. A gap analysis will help you find the differences between evidence-based care and current practice.

The hypothetical graph on the slide illustrates this concept. The green line with a diamond endpoint represents the ideal state of evidence-based care delivered consistently for every patient every day. The red line with a square endpoint represents the reality of care practices as they are today.

Slide 12: Unit-Based Gap Analysis

Say:

The American of Association of Critical Care Nurses, or AACN, developed a unit-based gap analysis tool and published it on their Web site. The tool is specific to implementing AACN’s "ABCDE" bundle, a group of evidence-based interventions—awakening and breathing trial coordination (A, B, C), delirium assessment and management (D), and early exercise and progressive mobility (E)—designed to be used at the bedside to prevent the unintended consequences of critical illnesses. This technical bundle for improving the care of mechanically ventilated patients will be explained with greater detail in a later module.

While designed to be used in conjunction with the ABCDE bundle interventions, the gap analysis tool can be effectively applied to any process within your specific unit. By using the Likert scale shown here, respondents can circle the frequency in which the process or action takes place.

The following slides provide examples of questions you can ask to assess your current processes for coordinating SATs and SBTs, managing delirium, and promoting early mobility.

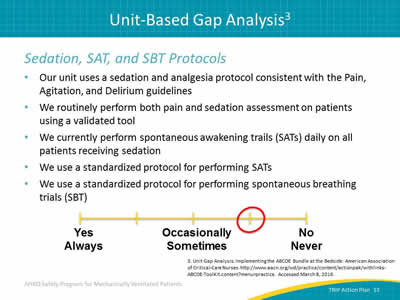

Slide 13: Unit-Based Gap Analysis

Say:

Here, the goal is to determine whether your unit consistently uses the AACN’s evidence-based recommendations for performing SAT and SBT protocols. As you ask yourself the following questions, indicate on the scale below how often these recommendations are followed in your unit.

Ask:

How often does your unit use a sedation and analgesia protocol consistent with the Pain, Agitation, and Delirium guidelines?

How often does your staff routinely perform both pain and sedation assessment on patients using a validated tool?

How often are daily SATs performed on all patients receiving sedation?

How often does your unit use a standardized protocol for performing SATs?

How often does your unit use a standardized protocol for performing SBTs?

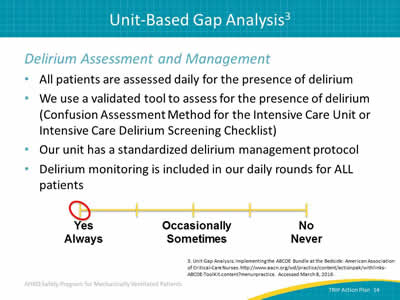

Slide 14: Unit-Based Gap Analysis

Say:

Here is an example of how to examine the processes your unit has in place to assess the presence of delirium in your patients. As you ask yourself the following questions, indicate on the scale below how often these recommendations are followed in your unit.

Ask:

Are all your patients assessed daily for the presence of delirium?

Does your unit employ a validated tool, such as the CAM-ICU or the ICDSC, to assess for delirium?

Do you have a standardized delirium management protocol?

Is delirium monitoring included in your daily rounds for ALL patients?

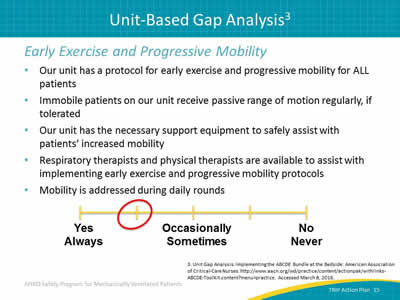

Slide 15: Unit-Based Gap Analysis

Say:

Since we are using the ABCDE bundle as an example, this final area is looking at the current state of your unit’s processes for early exercise and progressive mobility.

Ask:

Does your unit use a protocol for early exercise and progressive mobility?

Are immobile patients receiving passive range of motion regularly if tolerated?

Does your unit have the necessary support equipment to safely assist with increased mobility?

Are respiratory therapists and physical therapists available to assist with these measures?

Is mobility assessed during daily rounds?

Say:

As with the other examples, indicate your answers on the scale.

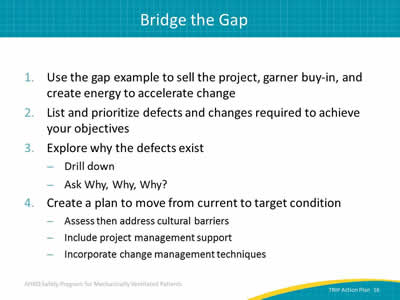

Slide 16: Bridge the Gap

Say:

From the current state to your future vision, this program aims to bridge that gap. A detailed gap analysis will help you sell the project to your key stakeholders, as well as build momentum to accelerate change. After you list the defects identified by your gap analysis, prioritize which defects to address first, as well as the changes required to achieve stated objectives.

As your team continues to explore where you have gaps, you can begin to identify and focus on the specific defects causing the gap.

Ask:

Why is this happening?

For example, if you are not turning off the sedation prior to an awakening trial, why is that happening?

Say:

Your nurse might respond, "Well, because I don’t have a standard order. The physicians don’t come around until after 10 o’clock in the morning and tell me to turn it off."

Ask:

Why don’t we have a standing order?

Say:

Perhaps it’s because it was never approved through the appropriate committee to have a standing order. Perhaps the protocol is outdated. Perhaps the orders are erroneously missing. It's those kinds of questions—why, why, why—that need to be answered to understand your current performance. Through this inquiry, your team will identify what you can do, what barriers are present, and what issues need to be addressed so that you can solve them. Then you will create a plan to move from the current state to your future vision of evidence-based consistent care. To implement and achieve that vision, address cultural barriers, include project management support, and incorporate change management techniques.

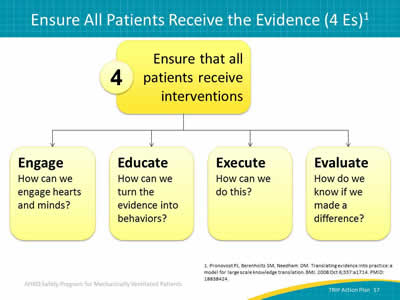

Slide 17: Ensure All Patients Receive the Evidence (4Es)

Say:

The final component of TRIP ensures that all patients receive the evidence, often called the four Es: engage, educate, execute, and evaluate.

Patient stories are powerful ways to engage your staff. Consider asking a patient or family member to share their story. Next, educate your staff on the evidence, and do so in ways that clearly indicate expected behaviors. This program employs technical bundles based on evidence. The third step is to execute.

Ask:

How can we do this?

Say:

Execution encompasses the adaptive component of change.

Ask:

How can you make it easier for your staff to do the right thing?

Say:

Frontline staff want to do the right thing; they want their patients to receive the best care. When implementing new procedures, make it easy for them to know what the correct procedure is and to perform it correctly.

Ask:

How will you know if you made a difference?

Are we doing what we said we should be doing?

Say:

This step involves evaluating your implementation. Before implementation, define your expectations. Collect data from baseline, throughout implementation, and after the initial intervention period ends. After implementation, evaluate your results.

Slide 18: Translating Evidence Into Practice

Say:

The TRIP framework helps you implement the technical interventions. But your first step is to create that gap analysis, which shows where evidence-based care delivery differs from the current practice. This can only be performed at the local level.

Slide 19: Summary

Say:

Gaps exist in ICU settings, especially surrounding sedation and mobility practices. A gap analysis defines the difference between your current practice and evidence-based consistent care. Develop action plans and set goals to improve the care of mechanically ventilated patients.

Slide 20: Tests of Change

Say:

In this section we will discuss ways to develop action plans and how small-scale tests inform quality improvement efforts that can be sustained in your clinical setting. Tests of change help teams close the gaps between current care delivery and evidence-based consistent care.

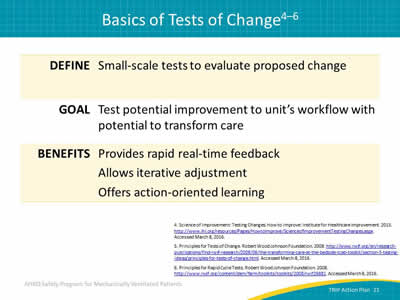

Slide 21: Basics of Tests of Change

Ask:

After you have identified gaps in care delivery, what can you do to close the gaps?

Say:

You may be familiar with tests of change under a different name such as small-scale rapid cycle improvement testing or PDSA, which stands for plan-do-study-act. Tests of change are small-scale tests to evaluate a proposed change.

The goal is to study potential improvements to care processes that have the potential to transform care in large and small ways. They provide rapid trial and error feedback in real time while minimizing the risk and impact. Because of the small scale, lessons learned provide opportunities for iterative adjustment, adjustments that can be immediately incorporated into future tests of change. Tests of change offer action-oriented learning in the appropriate context and setting. They can determine whether an idea could become sustainable improvement within your local context.

Ask:

Can you think of any reasons to employ small tests of change?

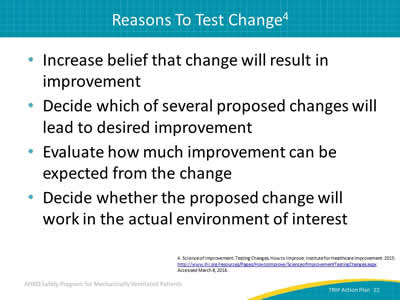

Slide 22: Reasons to Test Change

Say:

Small successes from tests of change can increase the belief that the change will result in tangible improvement. They can help determine which of several proposals will achieve the desired improvement. Tests of change can also provide insight about how much improvement can be expected from the change. A primary reason to conduct a test of change involves verifying that the proposed change will work in the local context.

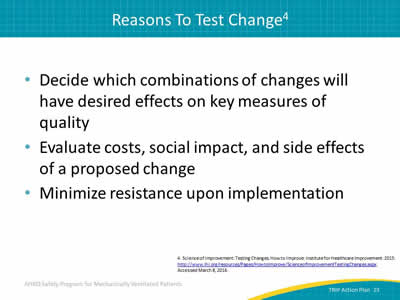

Slide 23: Reasons to Test Change

Say:

Tests of change offer the flexibility for you to decide which combination of changes will have the desired effects on key measures of quality. Results will help your team evaluate costs, social impact, and unintended consequences or side effects from a proposal. Done well, tests of change have the power to minimize staff resistance upon implementation.

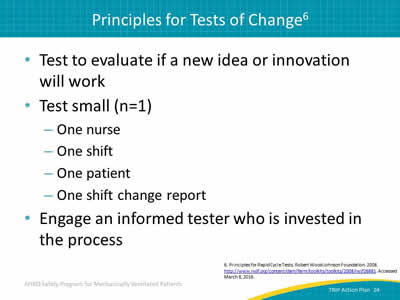

Slide 24: Principles for Tests of Change

Say:

The first principle of test of change evaluates the viability of a new idea or innovation and helps obtain the appropriate feedback needed to make a decision whether to adopt, adapt, or abandon your concept. Start your test very small, such as a single nurse, shift, or patient. Because the scale of the test is small, choose your tester carefully. Select someone interested in this particular idea, a receptive nurse or open-minded respiratory therapist. Tap that curious team member for your project or reward a staff member with a good idea.

Slide 25: Principles for Tests of Change

Ask:

So how quickly can you implement a new protocol in your unit?

Say:

We know that it takes some time and a significant amount of resources to implement change. Tests of change don’t necessarily need initial buy-in from every staff or team member. In addition, committee approval is not required nor is a mound of paperwork. Form an informed hypothesis backed by evidence, and collect quantitative or qualitative data. Depending on the nature of your test, you may need to address the committee after you have some data you can use to support the request. As data should drive all quality improvement efforts, data can facilitate committee approval as well. Remember to revise your proposal, as it may take many iterations to build successful and sustainable innovations.

Slide 26: Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) Cycle

Say:

So with these general principles in mind, let’s discuss the framework for how to perform tests of change. The Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle, or PDSA, is the core of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s model for quality improvement.

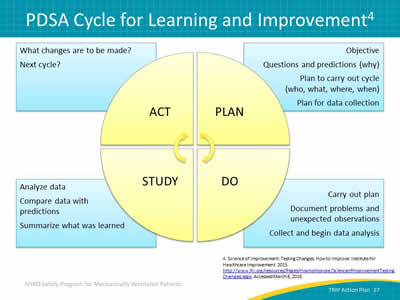

Slide 27: PDSA Cycle for Learning and Improvement

Say:

This diagram summarizes the steps of the PDSA cycle. While the process is cyclical, let’s discuss each step.

Slide 28: PDSA Step 1: PLAN

Say:

The first step is plan. Plan the test or observation. State your objectives and make a prediction about what will happen and why. Ask details to carry out the cycle, such as who, what, where, and when data needs to be collected? Before you begin, identify the information that will indicate if your test of change was effective.

Slide 29: PDSA Step 2: Do

Say:

The second step is do. This is where you try it. So, try out your test on a small scale, document any problems or unexpected observations, then collect and begin analysis of the data. You do not need a complicated data collection process. Remember, you’re trying to identify if this idea will work on your unit. So, the data collection doesn’t need to involve complicated spreadsheets or excessive data entry. Identify only the data you need to determine if it will work. Keep data collection as simple as possible.

Slide 30: PDSA Step 3: Study

Say:

Step three is study. Set aside time to analyze the data and study the results. Compare the findings with your predictions, then summarize and reflect upon what you have learned.

Ask:

Does this dataset offer confidence that this idea could work in your setting?

Slide 31: PDSA Step 4: Act

Say:

The fourth step is act. Refine the change based on what you learned from the test and modify test if necessary.

Ask:

Are you ready to adopt the test?

Are more adaptions needed?

Should this idea be abandoned?

Say:

The PDSA process is cyclical; step four is not the end of the process.

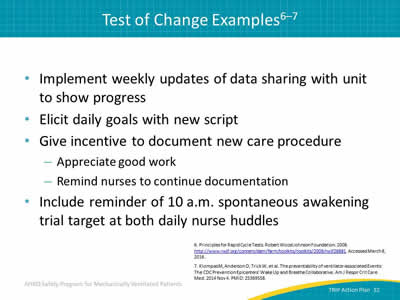

Slide 32: Test of Change Examples

Say:

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention-funded Wake Up & Breathe Collaborative shared some examples of tests of changes employed during their study. For example, one team implemented weekly updates for sharing data. Another unit used candy incentives to encourage data collection. Another team tested a reminder of awakening and breathing trials during morning nursing huddle.

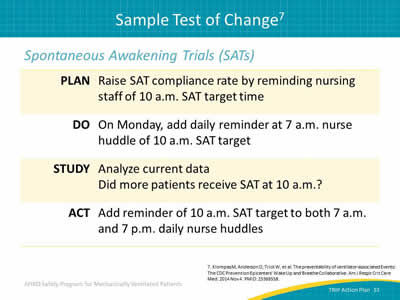

Slide 33: Sample Test of Change

Say:

Let’s expand on the previous example. Suppose compliance rates are low for specific process measures, like spontaneous awakening and breathing trials (SAT and SBT, respectively). You could plan a small test of change, a PDSA cycle to determine if a nurse huddle reminder would improve compliance rates. In the plan, you propose to raise your SAT and SBT compliance rate by reminding nursing staff to perform the tasks at 10 a.m. each day.

On Monday, you add a daily reminder during the nurse huddle at 7 a.m. to perform SATs and SBTs at 10 a.m. Next, you study and analyze your data. This is a very simple answer to the question: Did more patients receive SAT and SBTs at 10 a.m.? Perhaps you have some observations as well. Finally, the data support an action. You add a reminder of the 10 a.m. SAT and SBTs to both your 7 a.m. and 7 p.m. nurse huddles in hopes of expanding the success beyond one shift. You can tweak small interventions based on your local data.

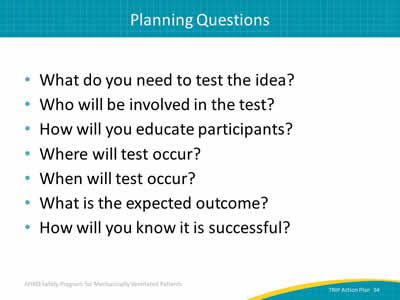

Slide 34: Planning Questions

Say:

These planning questions may be helpful as you plan your own tests of change.

Ask:

What do you need to test your idea?

Who will be involved in the test?

How will you share information with the participants?

Where will the test occur? One patient room or one nurse?

When will the test occur? One week or one shift?

What is the expected outcome?

How will you know it is successful?

Say:

Be sure to identify before the test of change what you expect and what quantifiable results will indicate success.

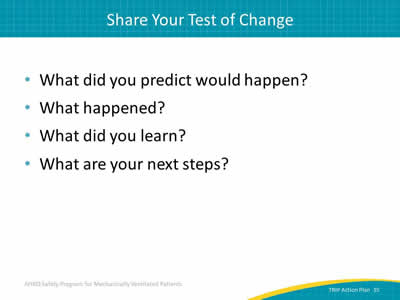

Slide 35: Share Your Test of Change

Say:

Be prepared to share your results. Summarize your test of change.

Ask:

What did you predict would happen?

What actually happened?

What did you learn?

What are your next steps?

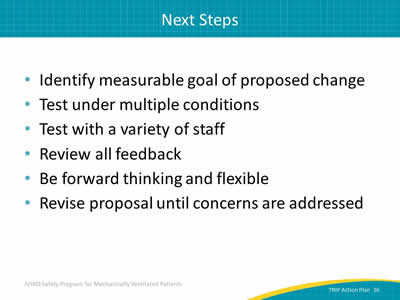

Slide 36: Next Steps

Say:

Tests of change provide a manageable way to pilot small interventions in your local context. Keep these steps in mind as you move toward implementing new initiatives. Identify a measurable goal of your proposed change.

Ask:

Does the proposal achieve the goal?

Say:

Test under multiple conditions and with a variety of staff. Different shifts and different providers will likely experience different concerns. Review all feedback and remain flexible and open-minded. Revise your proposal until all concerns are reasonable addressed.

Slide 37: Questions?

Ask:

Are there any questions?

Slide 38: References

Slide 39: References