Learn From Defects in Care of Mechanically Ventilated Patients: Facilitator Guide

AHRQ Safety Program for Mechanically Ventilated Patients

Slide 1: Learn From Defects in Care of Mechanically Ventilated Patients

Say:

In this module, we will discuss the Learning From Defects tool. It is a very useful process that enables frontline staff to identify root causes of problems they have identified and to reduce the risk of future harm.

Slide 2: Learning Objectives

Say:

At the end of this module, you will be able to describe the difference between first-order and second-order problem solving, list the contributing factors that make defects in care more likely to occur, and use the Learning From Defects or LFD tool to perform second-order problem solving. You will also be able to evaluate the effectiveness of your intervention by measuring baseline and post-intervention performance and present your findings to department leadership.

Slide 3: What Is a Defect?

Ask:

What is a defect?

Say:

A defect is anything you do not want to happen again or to ever happen. A defect can be a specific harm to a patient. It is also something that the nurses, doctors, and other clinicians find frustrating because it affects their workflow and could lead to future patient harm. Anything that might lead to preventable patient harm can be considered a defect.

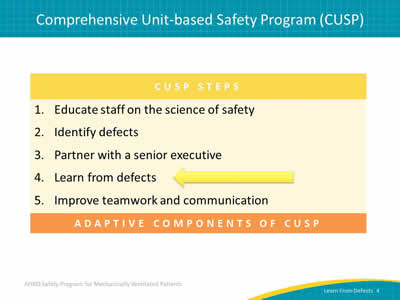

Slide 4: Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program (CUSP)

Say:

The Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program, CUSP, is a five-step program designed to impact safety climate by empowering staff to assume responsibility for safety in their environment. This module focuses specifically on the fourth step, which is to learn from defects. By understanding all the contributing factors of a defect, harms can be mitigated or eliminated. Learning from defects is considered an “adaptive” component of CUSP.

Ask:

Why is that important?

Say:

Adaptive work refers to achieving the behavior change required to effectively put into place the protocols, procedures, and other interventions we develop. Adaptive work requires a partnership between the frontline and executive levels; in the case of learning from defects, this means partnering to make sure all risks can be recognized and reduced. We will go into further detail on this partnership later in the presentation.

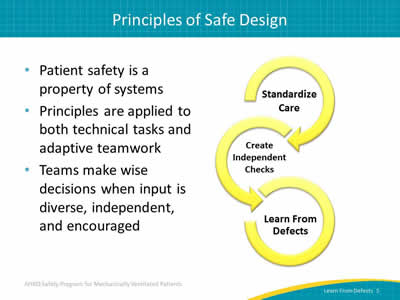

Slide 5: Principles of Safe Design

Say:

The principles of safe design include three major components—standardizing care, creating independent checks to support that care, and learning from defects. Learning from defects is one way to improve the design of systems; patient safety is a property of that system. The LFD tool does not blame individuals, but seeks root causes of errors. It supports the discovery process essential to prevent repeated errors and implement interventions. Teams make wise decisions when the input is diverse, independent, and strongly encouraged. When organizing your team, make sure it includes various practitioners—nurses, physicians, respiratory therapists, physical therapists, occupational therapists, pharmacists, and anyone who has a stake in the patient care process.

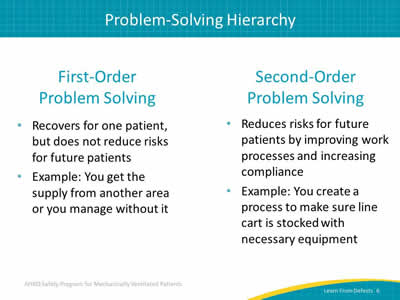

Slide 6: Problem-Solving Hierarchy

Say:

First-order problem solving resolves an issue for one patient but does not reduce the systemic risk that exists for future patients. First-order problem solving is what we do every day; we find that something is not working, so we develop a workaround or a quick solution. For example, if you are missing a required supply or piece of equipment, you may borrow it from another department or another room. While this fixes the immediate problem for your patient, it does not prevent the need for a future workaround. In fact, that workaround may actually harm another patient who is now impacted by the missing supply or equipment. While the immediate fix may be helpful under emergent circumstances, it does not prevent problems from happening in the future.

Ask:

What method of problem solving should we employ?

Say:

Instead of relying on first-order problem solving, practice second-order problem solving. Second-order problem solving focuses on identifying system issues rather than one-time solutions. It reduces risks for future patients by improving work processes and increasing compliance. An example of second-order problem solving would be creating a process to ensure that a line cart is stocked with necessary equipment. Asking the question, "What led to the need to search for and borrow the missing supply or equipment?" can lead to the implementation of an intervention which ensures that necessary supplies are available.

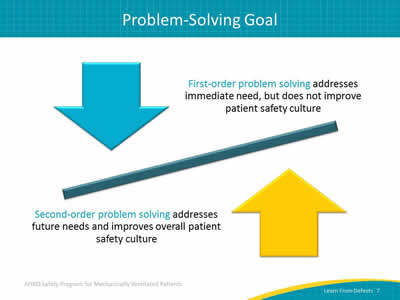

Slide 7: Problem-Solving Goal

Say:

First-order problem solving addresses the immediate need but does not improve or encourage patient safety culture. In fact, it often leaves staff frustrated and feeling that the system is not working. Why do they have to rely on a temporary procedure to take care of a patient? To improve and maintain a positive patient safety culture, ensure that problems are not only fixed for the short term but fixed in a way that can be sustained so that it can never happen again.

Second-order problem solving often allows staff to make a current process obsolete. Through the use of the LFD tool, a particular process, technology, or workflow can be redesigned to essentially error-proof the entire problem. Second-order problem solving addresses future needs and improves overall patient safety culture.

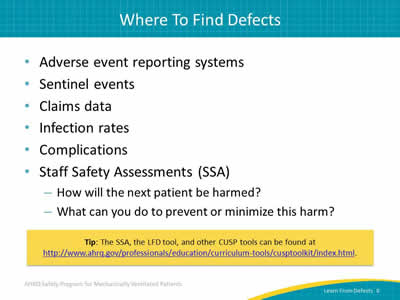

Slide 8: Where To Find Defects

Say:

You can find defects in many places. Adverse-event reporting systems are common in hospitals. Sentinel events, as defined by the Joint Commission, or any claims data from your legal department provide high-profile defects. Infection rates from hospital epidemiology and infection prevention are also sources of data of known complications. The most effective way to identify defects is to give your frontline providers a simple two-question survey called the Staff Safety Assessment or SSA. The questions are: How will the next patient be harmed, and what can you do to prevent or minimize this harm? The SSA, which is a tool of CUSP, is a valuable way to gain insights into problem areas and find solutions.

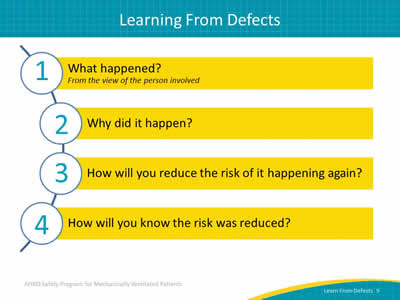

Slide 9: Learning From Defects

Say:

The LFD tool provides a structured approach to help your teams identify system factors that contribute to defects, plan improvements, and sustain those improvements. Because this tool helps you to look at defects at a systems level, the solutions you create are more likely to be lasting ones.

Whether your team uses this tool or develops its own tool, you should ask these four basic questions when considering a defect.

- What happened?

- Why did it happen?

- How will you reduce the risk of the defect happening again?

- How will you know the risk is reduced?

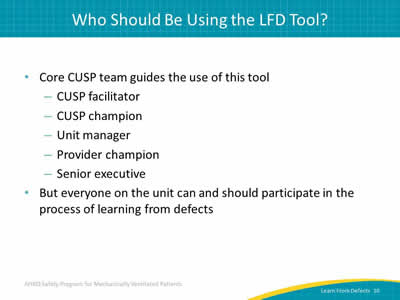

Slide 10: Who Should Be Using the LFD Tool?

Say:

The CUSP team guides the use of the LFD tool. The CUSP team consists of the facilitator, the champion, the unit manager, the provider champion, and the senior executive. It is not limited to these roles, however. In fact, anyone on the unit who is involved in the care of patients can and should participate in the process of learning from defects.

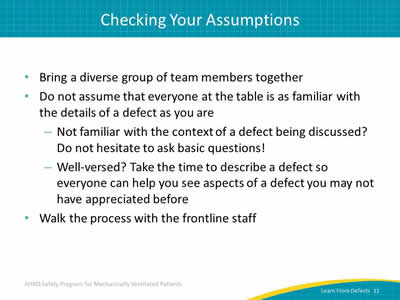

Slide 11: Checking Your Assumptions

Say:

CUSP brings together a diverse group of team members. Talk to your team and be sure that all stakeholders are identified. Your core CUSP team will need to augment the team with representatives that correspond to the defect being addressed. Once the appropriate team has been assembled, do not assume that everyone is aware of the nuances of the problem.

Ask:

How can you make sure that everyone is aware of the problem?

Say:

Encourage everyone to ask questions. Once all members of the team have a firm understanding of the defect, take the time to describe the entire situation so that team members can point out aspects of the defect that may have been overlooked. To ensure that each person understands the full nature of the defect and has the opportunity to share their experience, walk the process with the frontline staff. Walking the process is a robust method for determining how a defect happened.

Slide 12: What Happened?

Say:

Select a defect to explore. When exploring what happened, the entire team puts itself in the place of those involved; it gets in the middle of the event as it unfolded. Listen to your colleagues during this process. Seek to understand the process; don’t judge the individuals. This will enable you to move away from the tendency to accuse, blame, criticize, or deny. Instead, focus on what happened and what contributed to the event. Ask clarifying and followup questions. When things are not clear, or when two pieces of information seem to contradict each other, ask more questions. Try to discover what exactly led to the defect. Why were particular decisions made? Explore both the reasoning and the emotions behind what happened. Individuals involved in a defect are often put in a position which leads to patient harm because of the system itself, rather than because of a sole individual’s mistake. To fully understand the situation and the defect, the team must understand their reasoning and how they reacted. The system might have made the mistake or defect almost inevitable.

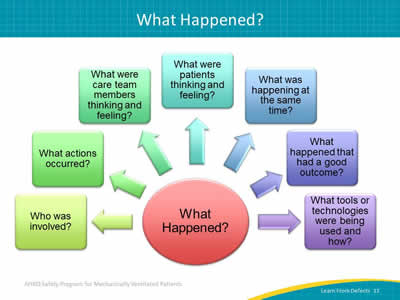

Slide 13: What Happened?

Say:

Take a moment to think of a defect you have experienced, either as a health care provider or as a patient. Now, ask as many relevant questions as you can think of to discover what led to the defect.

Ask:

Who was involved?

What actions occurred?

What were the team members thinking and feeling?

What was the patient thinking and feeling?

What was happening at the same time?

What happened that had a good outcome?

What tools or technologies were being used and how?

Say:

Asking these questions, and others, can help you understand how a defect occurred.

Slide 14: What Happened?

Say:

Try to find out what occurred in real time. After all questions have been posed, reconstruct a timeline of the defect based on the answers to those questions. Visualize and map the process by creating diagrams or sketches on whiteboards or flip charts to better understand the details of what led to the defect. Simulate the process through role playing. Ask your colleagues, "What decisions did people make at certain steps? Where do they tend to go wrong?" While moving through this exercise, remember that to create lasting change, you need to be aware of the impact of people’s internal motivators such as values, attitudes, and beliefs. They are essential components of any workable solution.

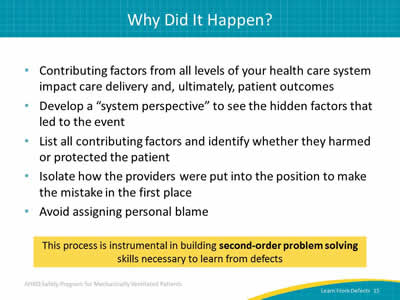

Slide 15: Why Did It Happen?

Say:

Next, move on to why the defect happened. With a timeline and process map created, consider the contributing factors from each level of your health care system and how each impacts care delivery and patient outcomes. Develop a "system perspective" to see the hidden factors that led to the event. In doing so, you will avoid the accuse-and-blame approach. Use the LFD tool to list and rate all contributing factors and to identify whether they harmed or protected the patient. Isolate how the providers were in the position to make a mistake, rather than approaching the defect from a "who did what" point of view. By exploring and getting to the root cause of the defect, your team is taking the first instrumental step in problem solving. Only then can you progress to second-order problem solving to improve the long-term patient safety culture.

Slide 16: System Factors Impact Safety

Say:

Each level of the health care delivery system matters.

Ask:

What levels can you identify within your health care delivery system?

Say:

The following are all factors that impact safety in the health care system:

- Institutional factors such as the economic and regulatory state of your organization.

- Hospital factors such as financial resources and organizational structures.

- Departmental factors, such as staffing levels and managerial support.

- Work environment factors, such as shift patterns and equipment maintenance.

- Team factors, such as team structure and quality of verbal communication.

- Individual provider factors, such as knowledge, skills, and motivations.

- Task factors, such as clarity of structure and accuracy of test results.

- Patient characteristic factors, such as the complexity of their condition, personality, and communication abilities.

Look at each of these system factors and consider how each can carry a defect that leads to patient harms.

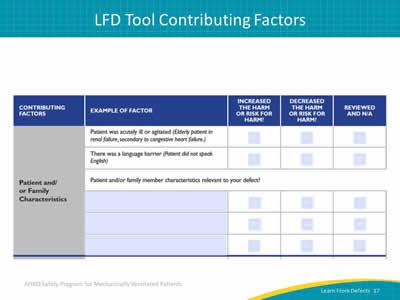

Slide 17: LFD Tool Contributing Factors

Say:

Document the institutional, hospital, task-level, patient, and family contributors using the LFD tool. Here is an example of a contributing factors chart from the LFD tool. Use this tool to document patient and family characteristics and if they increased or decreased the harm or risk for harm.

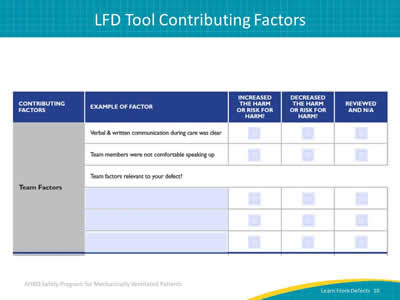

Slide 18: LFD Tool Contributing Factors

Say:

Repeat this exercise and document any team factors that contributed to the defect.

Ask:

What factors contributed to, minimized, or prevented harm?

If verbal or written communication during care was not clear, did it increase or decrease the harm or risk for harm?

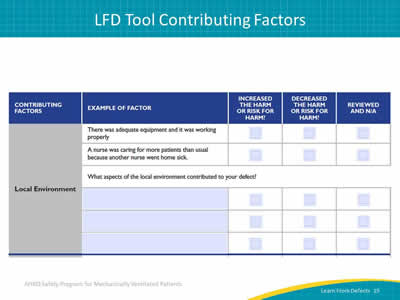

Slide 19: LFD Tool Contributing Factors

Say:

Do the same with factors in your local environment.

Ask:

What factors in your environment could contribute to a patient safety issue or defect?

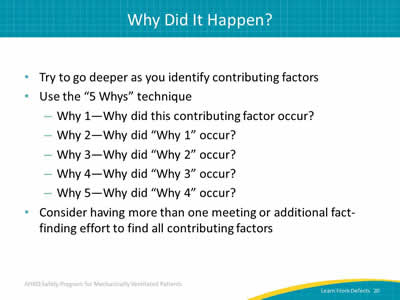

Slide 20: Why Did It Happen?

Say:

As you identify contributing factors, try to drill down and use the "5 Whys" technique. Why did one contributing factor lead to another contributing factor? And why did the next factor lead to the next? These analyses may require that you meet several times and engage in fact finding activities to identify the contributing factors and understand why a defect happened.

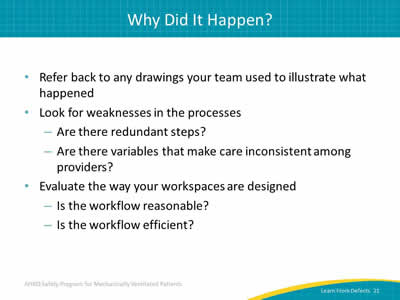

Slide 21: Why Did It Happen?

Say:

Make the "whys" visual. If your team created a process map or a drawing to illustrate what happened, use it to map out what happened and include the "why" under each defect. Use colored labels, colored sticky notes, or markers—whatever will engage your entire group. An issue can become much clearer when the entire team can see the whole picture at one time. As you examine the defect, look for weaknesses in the processes. Are there redundant steps and are there variables that make care inconsistent among providers? Evaluate the way your workplaces are designed and how they impact workflow. How do the workplaces and workflows impact patient care and the overall care process?

Slide 22: Why Did It Happen?

Say:

Think about the culture of safety in your unit and hospital. Was there something about the overall culture or the "people side" that led to the defect? Consider that each person carries a set of attitudes and behaviors that can contribute to the defect. Are there aspects of your patient safety that inadvertently promote doing the wrong thing or engaging in a risky workaround? Recognizing the defects hindering a strong patient safety culture is the first step to building a culture of safety in your unit and hospital.

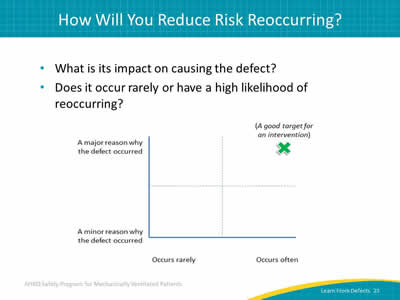

Slide 23: How Will You Reduce Risk Reoccurring?

Ask:

How will you reduce the risk of it happening again?

Say:

When learning from defects, select each contributing factor to assess its impact on causing the defect.

Ask:

Does the defect occur rarely or have a high likelihood of returning?

Say:

Focus on a defect that carries the greatest risk of harm to the patients, is most likely to occur, and has a likelihood of intervention. Each defect has many contributing factors, making it difficult to immediately address each one. So, prioritize the contributing factors by asking if that contributing factor was major or minor and how frequently the contributing factor occurs. As a general rule, consider factors that occur often as major reasons for the defect. All contributing factors will need to be addressed, so use this prioritization grid to help your team develop an achievable action plan.

Slide 24: How Will You Reduce Risk Reoccurring?

Say:

After selecting a defect to focus on, encourage all team members to brainstorm possible solutions. Again, use a flipchart, a chalkboard, or a whiteboard along with Post-it notes as a way to capture and organize all possible contributing factors and solutions. Do not evaluate or criticize an idea. Be creative and encourage each team member to "think outside of the box." Even "wild" ideas should be encouraged and displayed for everyone to see. Having gained the insights of the entire team, prioritize the most important contributing factors as well as the most beneficial interventions. Take advantage of the diversity of your interdisciplinary team. The senior executive can offer organizational vision and information that the organization can and cannot support. Utilize the wisdom and knowledge of the front line staff as well as your team members’ connection throughout the organization.

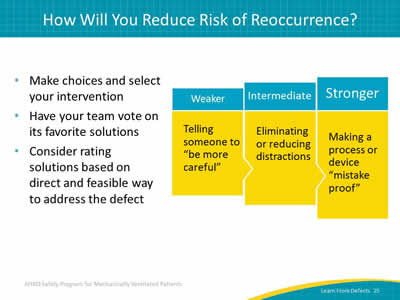

Slide 25: How Will You Reduce Risk of Reoccurrence?

Say:

After brainstorming and then prioritizing the list of targeted interventions, make choices and select your intervention. As noted in the previous slide, strongly consider those interventions likely to have the biggest impact and evaluate potential barriers to intervention. Have your team vote on the solutions it favors. One way to do this is by using the dot voting method. After posting the compiled list of possible interventions, give each member three dot stickers. Each dot sticker will represent a vote. Instruct them to place a dot next to each intervention they like. They can place all three votes on a single idea or spread them out. Then, rate the solutions or interventions based on frequency and expected impact. Strive to implement interventions that will have an intermediate or strong impact. For example, telling someone to "be more careful" is weaker than eliminating competing distractions or making a process or device "mistake proof."

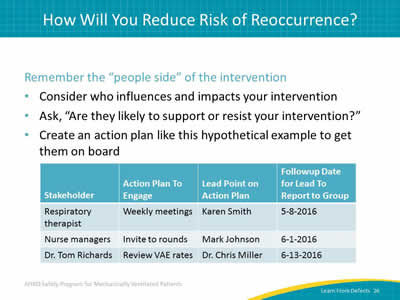

Slide 26: How Will You Reduce Risk of Reoccurrence?

Say:

Remember the people side of the intervention. Ensure the new intervention blends into the current workflow so that it can serve its purpose of preventing harm to patients. Consider all stakeholders who influence and impact the intervention and ask if there will be resistance to the intervention. Do not ignore the resisters. As difficult as they may seem, they usually offer kernels of truth. Take time to present plans and solicit feedback; they may surprise you and help make an intervention far stronger and more achievable. Create an action plan to get buy-in to the intervention. Make a list of your stakeholders and their names to determine who will be a part of the implementation process. Create an action plan and assign a lead point person to follow up on that action plan by a specific date.

Slide 27: How Will You Reduce Risk of Reoccurrence?

Ask:

Getting people engaged and involved in the process is difficult, so how can we better involve the team to reduce the risk of another defect?

Say:

Utilize the wisdom of your interdisciplinary team to overcome barriers and solve problems. Ensure that there is a thorough understanding of the intervention and that the details are clear with no ambiguity. If people are not certain of the expectations, the intervention will fail. Create workflow changes and process changes to ensure consistent implementation of the intervention.

Slide 28: How Will You Know Risks Were Reduced?

Ask:

How will you know the risks were reduced?

Say:

You first need to confirm that your all staff members, including your stakeholders, know about the interventions. Are they implementing the intervention as intended? When examining whether the defects were reduced, remember to ask the frontline staff and stakeholders. While subjective evaluations can provide valuable qualitative information, focus on data-driven quantitative metrics for evidence that the risk of the defect reoccurring has been reduced.

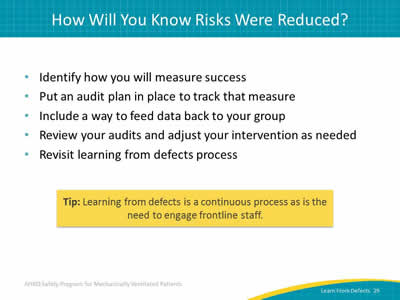

Slide 29: How Will You Know Risks Were Reduced?

Say:

Plan how you will measure success. Implement an audit plan to track that intervention and to determine if the risk for a defect was reduced. After completing the audits, make any necessary adjustments. Share the data with the frontline staff and make sure to keep them involved by letting them know that their interventions are effective. If you are not achieving the desired results, start again by revisiting the learning from defects process; review the original defect and all of the brainstorming notes. Identify any new information and secondary defects introduced by the intervention. Learning from defects and engaging the frontline staff is a continuous process.

Slide 30: How Will You Know Risks Were Reduced?

Ask:

Are there other ways to assess whether risks were actually reduced?

Say:

One quantitative way is to identify and document the effectiveness of your intervention by including baseline and post-intervention data in your intervention evaluation plan. Audits and evaluations require feedback to be impactful and meaningful. When you have all the relevant data, make sure to share your findings with leadership and your frontline providers.

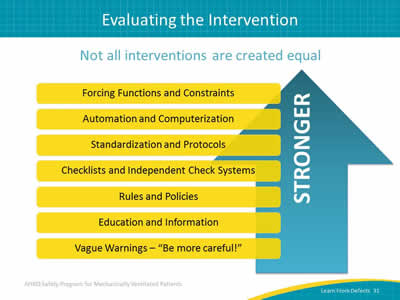

Slide 31: Evaluating the Intervention

Say:

When evaluating an intervention, consider its impact and strength.

Ask:

Why is simply warning individuals to be more vigilant about safety a weak intervention?

Say:

It is a weak intervention because humans are fallible and cannot be vigilant about all things at all times. Education is important, but on its own, it is also a weak intervention. Rules and policies are stronger interventions, but not everyone will read or remember the policies. Creating checklists and implementing independent check systems are stronger interventions than giving a vague warning or providing education and information. Creating standardization and protocols, automating systems, and forcing functions and constraints are the strongest types of interventions.

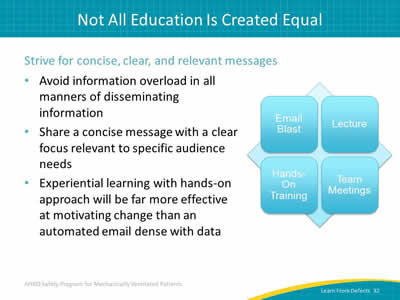

Slide 32: Not All Education Is Created Equal

Say:

Part of the reason that education alone is a weak intervention is that not all methods for educating are effective. Depending on the defect, some educational strategies are better than others. While you can reach a broad audience, email blasts are not effective for teaching how to do a job better or to make sure patients are safer. Email blasts can cause information overload and do not engage the recipient. Lectures may be more effective, given the face-to-face nature of that session; however, lectures lack the hands-on approach of other methods.

Focus on experiential learning by holding team meetings that allow members to share their educational experience. There is an interaction between the learners and the teacher. This type of education is stronger than emails and one-way lectures. Studies have shown that hands-on training events are effective because the real engagement helps imprint the information being taught. Asking people to read, learn, and apply the learning enables people to form memories of the process. Engaged learning is a very strong educational method. When conducting an educational intervention, avoid information overload and strive for concise, clear, and relevant messages.

Slide 33: Action Plan

Say:

Now you are ready to create an action plan to get started identifying and learning from defects.

Ask:

What should this action plan look like?

Say:

First, review the LFD tool with your team. Following that, work with the team to prioritize all defects. Then, select at least one defect in your intensive care unit to address and resolve per month. Explore and identify the top three contributing factors of the defect. With supporting data, show your staff the reduced risks for patient harm. Finally, post success stories of reduced risks to patient safety and share the positive impact their interventions have had on patients. Celebrate your successes!

Slide 34: Questions

Slide 35: