Ventilator-Associated Event Surveillance: Facilitator Guide

AHRQ Safety Program for Mechanically Ventilated Patients

Slide 1: Ventilator-Associated Event Surveillance

Say:

This module will focus on ventilator-associated event surveillance and how it can be used in your unit.

Slide 2: Learning Objectives

Say:

After this session, you will be able to discuss the ramifications of ventilator-associated events (VAE) and describe the methods to evaluate them. These are both important subjects, and while you may already be familiar with them, it is always important to look at topics in a new way. After this review of VAE surveillance, we will identify ways to use this data to drive improvement. Improvement is the ultimate goal.

Slide 3: Why Collect VAE Data?

Ask:

Why is VAE data collected? Why is it so important that surveillance information be shared in each intensive care unit or ICU?

Say:

Mechanically ventilated patients are at risk from their many comorbidities as well as from mechanical ventilation itself. Harms that can befall these mechanically ventilated patients range from acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) to atelectasis and ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP). Tracking these harms is important to the hospital but is also vital to improving the care these patients receive. Surveillance results can give providers a way to monitor and improve this care by connecting the dots from the event back to possible causes.

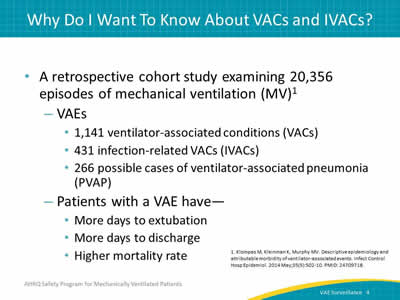

Slide 4: Why Do I Want To Know About VACs and IVACs?

Say:

Here is another article by Klompas et al. In this retrospective study of more than 20,000 episodes of mechanical ventilation, we see that patients with a VAE are more likely to have a longer duration of mechanical ventilation, a longer length of stay, and a higher mortality rate than do mechanically ventilated patients without a VAE.

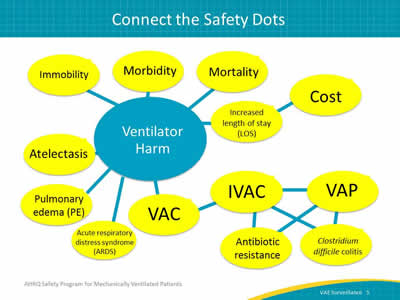

Slide 5: Connect the Safety Dots

Say:

The use of any invasive device can lead to harm. Devices include urinary catheters, central lines, mechanical ventilation equipment, and many others. While these are all life-saving events, there is a potential for harm. In this schematic you can see some of the causes for and outcomes associated with ventilator harm. Patients on mechanical ventilation are at risk for conditions such as ARDS, atelectasis, and pulmonary edema. These are classified as ventilator-associated conditions or VACs. IVACs can contribute to infections such as Clostridium difficile and to antibiotic resistance because of antimicrobial usage. VAP, in particular, has high morbidity and mortality rates. All of these conditions can increase length of stay and cost for the patient’s care.

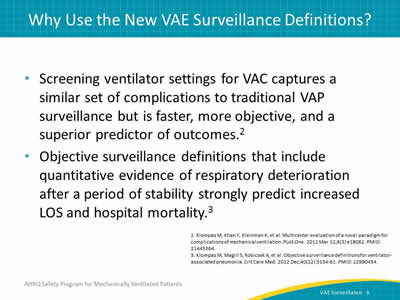

Slide 6: Why Use the New VAE Surveillance Definitions?

Say:

Dr. Mike Klompas et al. published an article in 2011, evaluating the complications of mechanical ventilation. It concluded that the surveillance definitions for VAC capture a similar set of complications to traditional VAP. However, surveillance for VAE is faster, more objective, and a superior predictor of outcomes. This surveillance also includes quantitative evidence of respiratory deterioration after a period of stability.

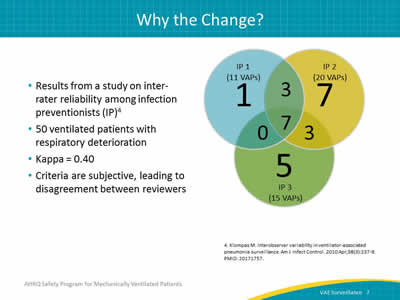

Slide 7: Why the Change?

Ask:

Why is it important to change the surveillance definition?

Say:

One of the main reasons is inter-rater reliability. This occurs when two people separately look at the same set of criteria and do, or don’t, come up with the same conclusion. The traditional VAP surveillance definition included radiological evidence of pneumonia. It’s very difficult even for a clinician to look at an image and make a definitive diagnosis. Often the radiologist will state that there is a moderate right pleural effusion with possible overlying pneumonia. In other words, it might or might not be pneumonia. The attending physician can’t differentiate without clinical signs and symptoms, and neither can the IPs performing the surveillance. On the right side of this slide is a figure developed by Klompas et al. looking at interobserver agreement in VAP surveillance. It is interesting because there is one IP who found 11 VAPs, one who picked up 20, and one who picked up 15. In addition, each of these IPs only agreed on seven of the VAPs using the exact same definition. As a result of discrepancies, of which these are an example, a standardized, objective definition is needed.

Slide 8: Why the Shift?

Say:

Shifting the focus of surveillance from pneumonia alone helps us understand the importance of all these complications. It helps us focus on the importance of preventing all complications resulting from pneumonia, not just the pneumonia itself. When the definitions are objective, unit staff can spend time focusing on what went wrong and how to fix it rather than debate whether the event was actually VAP.

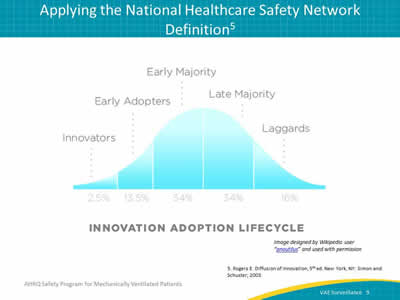

Slide 9: Applying the National Healthcare Safety Network Definition

Say:

This is Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovation. For this type of work, we have to look at two major steps: dissemination and diffusion. Dissemination requires formal messages, policies, and procedures, to be sent out and established. On the other hand, diffusion comes from your culture. It stems from people directly communicating and engaging with each other. It involves people who are excited about identifying opportunities to prevent infections. Keep in mind, not everyone in your unit or hospital will be quick to accept change. Those who take longer to adopt and apply the new National Healthcare Safety Network definitions remain valuable members of your team, and examining the different reasons for their hesitation may lead to an additional understanding of how to diffuse the message to others. While this work may be difficult, it’s important work that makes a difference. Just remember, change takes time and patience.

Slide 10: Broadening the Surveillance

Say:

The definition for VAE is intentionally broader than the traditional VAP surveillance. The research has shown that there are conditions associated with mechanical ventilation that consistently reoccur. These include ARDS, pulmonary edema, thromboembolic disease, and sepsis. Sepsis, for instance, is a complication well known for patients on mechanical ventilation. As we connect the dots to harm, it’s important to look at the clinical ramifications of VAE. We know that respiratory deterioration in previously stable patients is definitely a risk factor for increased morbidity and mortality. It’s necessary to look at these issues.

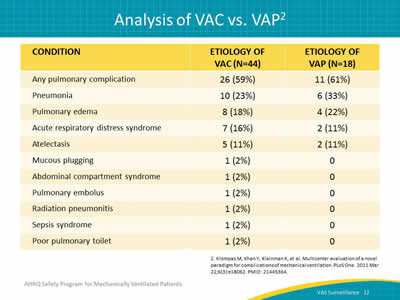

Slide 11: Analysis of VAC vs. VAP

Say:

Further research from Klompas et al. evaluated a novel surveillance paradigm for VACs, defined by a sustained increase in patients’ ventilator settings after a period of stable or decreasing support. In a qualitative analysis, a blinded critical care physician reviewed randomly selected patients with VAC or VAP, as defined by the protocol.

Slide 12: Analysis of VAC vs. VAP

Say:

The comparison of these patients shows that similar proportions of VAC and VAP events are attributed to pneumonia, pulmonary edema, ARDS, and atelectasis. The research showed that screening ventilator settings for VACs captures a similar set of complications to traditional VAP surveillance but is faster, more objective, and a superior predictor of outcomes.

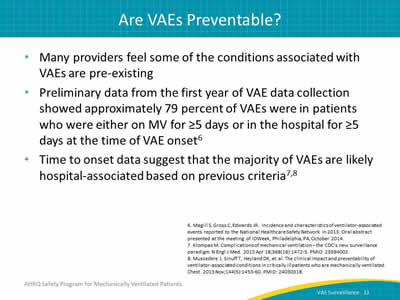

Slide 13: Are VAEs Preventable?

Say:

The question on many clinicians’ minds is, are VAEs preventable? Many providers feel some of the conditions associated with VAEs are pre-existing. However, Magill et al. presented an abstract in October 2014 showing that approximately 79 percent of VAEs reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network in the first year of the definition were patients who were on mechanical ventilation for more than 5 days at the time of onset. The characteristics of these patients differed from those who had been determined to have traditional VAP. This time to onset data suggest that the majority of VAEs are likely hospital-associated.

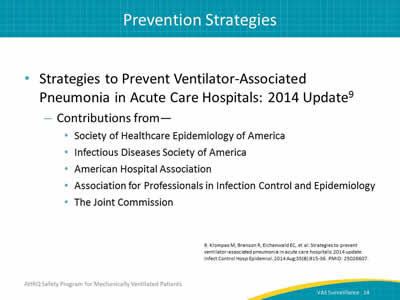

Slide 14: Prevention Strategies

Ask:

How are VAEs prevented?

Say:

The Society of Healthcare Epidemiology of America has published a set of strategies gleaned from the literature for the prevention of VAP in acute care hospitals. Many of these strategies can be used to prevent both VACs and IVACs.

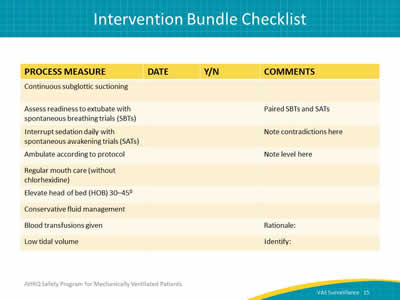

Slide 15: Intervention Bundle Checklist

Say:

This is an example of a quick checklist. You may have an electronic health records system, but it helps to just gather the data and look at it for each patient.

Ask:

Did the patient have daily spontaneous awakening trials? Were these trials paired with the spontaneous breathing trials? Was the patient’s head of bed elevated? Was the patient mobilized?

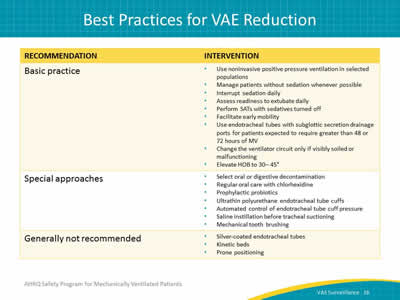

Slide 16: Best Practices for VAE Reduction

Say:

Some of the basic practices listed here have evidence that the intervention decreases the duration of mechanical ventilation. These same interventions were used to prevent VAP when we used the traditional surveillance definitions. These same interventions may also help with VAC prevention as well. The special approaches listed here may have risks associated with their use, but they may have their place in certain situations or patient populations.

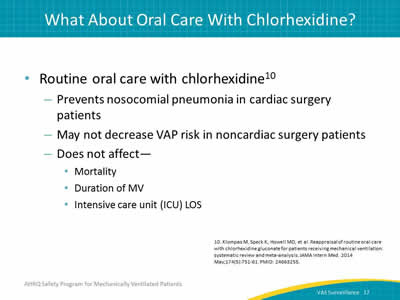

Slide 17: What About Oral Care With Chlorhexidine?

Ask:

Why is oral care using chlorhexidine included in the special approaches?

Say:

Routine oral care with chlorhexidine does prevent nosocomial pneumonia in cardiac surgery patients. However, it may not decrease the VAP risk in noncardiac surgery patients. It’s also been shown not to affect mortality, the duration of mechanical ventilation, or the length of stay in the ICU.

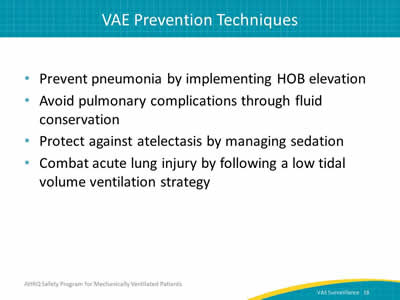

Slide 18: VAE Prevention Techniques

Say:

VACs occur for many reasons. However, determining the causes of these events can be daunting. These are a few suggestions for how to handle certain issues. For pneumonia—was the head of the bed elevated? For pulmonary edema—was there fluid conservation? For atelectasis—check the RASS or SAS scores. For acute lung injury—was a low tidal volume ventilation protocol used for the patient?

Slide 19: Getting Started on Prevention

Ask:

Where to start?

Say:

It’s important from a preventative strategy to look at both processes and outcome measures. It’s also important to collect process measures to make sure that the staff in your ICU is implementing the interventions you are focusing on. If you can do "data rounds" and collect the data in person, you can help staff focus on these interventions during conversations with them at the bedside. This dialogue can often help with understanding where the staff is with acceptance and engagement with the program. Data collection will also help you track your progress over time.

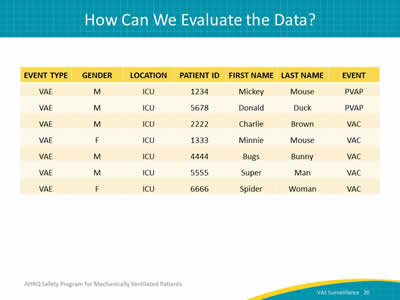

Slide 20: How Can We Evaluate the Data?

Ask:

How can you use the VAE data?

Say:

The first thing to do is to look at your cases. Use a line list like this. Once you determine the cases, you can look at whether each was a VAC, IVAC, or PVAP and then start to investigate your cases.

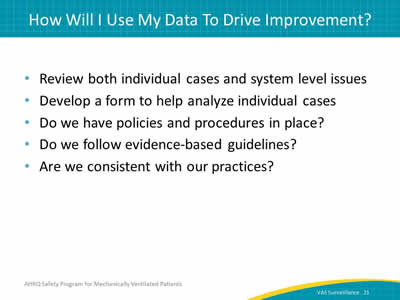

Slide 21: How Will I Use My Data To Drive Improvement?

Say:

Let’s look at VAC rates and your data. Common questions people ask are, "What do these rates mean? Should I have a zero VAE rate? What do I have to consider when I look at my data and prevention?"

The first step is to review the cases as we discussed earlier. Look at defects and determine if there is a system-level defect that is causing the problem. Ask five staff members the questions, "How do we do this? What is the policy?" If you get the same answer, you probably have good congruent validity, and you may assume your policies may be hardwired. However, if they look at you like deer in headlights, there may be other opportunities to hardwire the policies. One problem some sites have is coordinating the spontaneous awakening and spontaneous breathing trials. If this is one of your problems, are the nursing and respiratory therapy staffs working together to make sure this happens? If not, why? Are there policies and procedures in place to assure that these interventions happen? Is the staff really following the guidelines? Are we consistent with these practices? Do we make sure each patient receives best practice-based care every day?

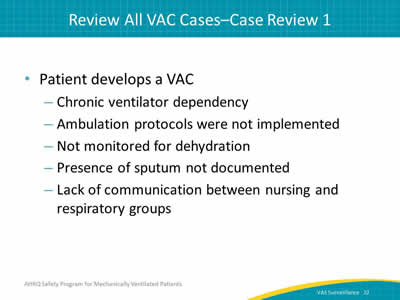

Slide 22: Review All VAC Cases—Case Review 1

Say:

Look at your cases to see what is happening and why. Here we have a patient who has developed a VAC, in which the origin was a mucus plug. The patient has a chronic ventilator dependency. He was not mobilized appropriately. He was dehydrated, his sputum was not documented, and the nursing and respiratory staffs weren’t communicating with each other. Just by looking at this one simple case, we can see several opportunities for improvement. Documentation, monitoring, and communication could be improved. Mobilization didn’t take place, so make sure to engage in the policies and protocols.

Slide 23: Case Review 2

Say:

Let’s look at another case. Ms. X is a 76-year-old woman. She was admitted to the ICU with septic shock and required a large volume fluid resuscitation. She was intubated and placed on a ventilator. She was stable until day 6 but had progressing oxygenation demands that led to the development of a VAC.

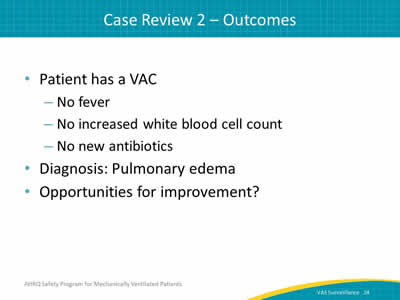

Slide 24: Case Review 2—Outcomes

Say:

She didn’t have a fever, increased white blood cell count, or new antibiotics. She had pulmonary edema. Where are the opportunities for improvement? Perhaps in handling fluid resuscitation and subsequent recovery.

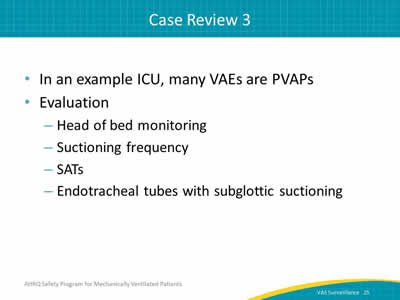

Slide 25: Case Review 3

Say:

In this next case, an ICU has a high VAE rate. A large portion of these VAEs are PVAPs. Staff looked at their head of bed monitoring and the frequency of their suctioning. They checked to make sure they were doing their spontaneous awakening trials daily and began to evaluate the possibility of obtaining subglottic suctioning endotracheal tubes for use in their patients.

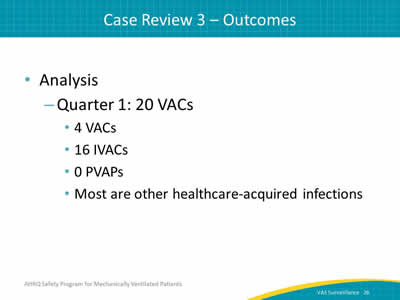

Slide 26: Case Review 3—Outcomes

Say:

Finally, after these interventions, they analyzed their data. They found that the majority of their VAEs were now VACs and IVACs. Many of the IVACs were due to other healthcare-acquired infections. The longer patients are on a ventilator, the more likely they are to have an increased ICU and hospital stay, and the more likely they are to develop a healthcare-associated infection. Therefore, the next step for this unit is to focus on interventions to decrease length of stay and shorten time of mechanical ventilation as much as possible.

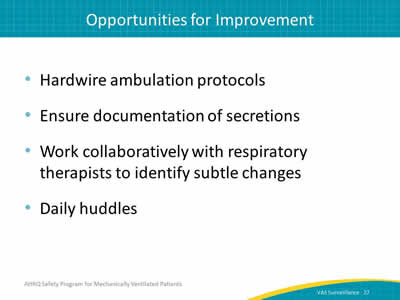

Slide 27: Opportunities for Improvement

Say:

So how can your unit improve? Think about these examples and the interventions discussed. Ensure documentation of secretions. Work collaboratively with respiratory therapists to identify subtle changes in your patients’ condition. Make sure you have a daily huddle to discuss each patient. Make sure everyone is educated and trained appropriately. Audit care to assure that patients are receiving the best practice-based care every day. Also be sure to check the vent settings. Are any of the settings based on provider preference rather than on clinical symptoms? Is there an opportunity to educate the provider, or respiratory therapy staff, on low tidal volume ventilation? Were mobility protocols followed? Check on all the elements of appropriate care for this mechanically ventilated patient. If the patient didn’t receive the best care, you can use the Learning From Defects tool to help you problem solve and find solutions for your subsequent patients.

Slide 28: Know Your Data

Say:

At the end of the day, surveillance is a critical component of every quality improvement effort. You can’t prevent VAEs if you can’t measure them. It’s easy to get bogged down in the day-to-day events, but surveillance is crucial.

Slide 29: The Bottom Line

Say:

In terms of the bottom line, we know VAEs are associated with increased mortality rates as well as ICU and hospital length of stay. Make sure that you track and document processes of care, as well as outcomes. Share rates of implementation with staff. They want to know how well they are doing and where there is room for improvement, so sharing outcomes with them will allow them to see the results of their efforts. Investigate events and find the causes to drive change in practice.

Slide 30: Questions?

Ask:

Are there any questions?

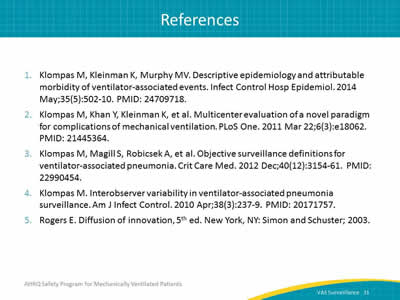

Slide 31: References

Slide 32: References