Building Your SSI Prevention Bundle: Facilitator Notes

AHRQ Safety Program for Surgery

Slide 1: Building Your SSI Prevention Bundle

Say:

In this module, you’ll learn about using building a local bundle to reduce surgical site infections.

Slide 2: Learning Objectives

Say:

After reviewing this module, you will be able to—

- Develop and implement a surgical site infection or SSI reduction goal and prevention bundle that addresses up to three surgical care processes your team has identified for improvement.

- Understand how to use the results of your staff safety assessment to build a bundle.

- Review how to initiate audits of your processes.

- Create a performance goal (improvement in outcome) for your team.

- Learn how to proceed with improvements that do not have a strong evidence base.

- Locate safety program for surgery resources on the project Web site.

Share what you have learned with your teams.

Slide 3: Background

Say:

Colon surgery has some of the highest wound infection rates of any procedure. In the literature, the rates range from about 10 to 30 percent. Especially in colon surgery cases, patient with infections stay in the hospital longer, are more likely to be readmitted, have a greater need for reoperation, and have a higher mortality.

There are also less tangible or less direct consequences—such as lost work and the impact on family and friends who need to help care for patients with wound infections.

There’s also the cost consideration. Estimates are that wound infections cost the health system anywhere from about $6,200 to $15,000 per patient. The cost depends on the type of wound infection, whether it’s a superficial infection—which costs about $3,000 extra—or an infection in the abdominal cavity, which costs upwards of $15,000.

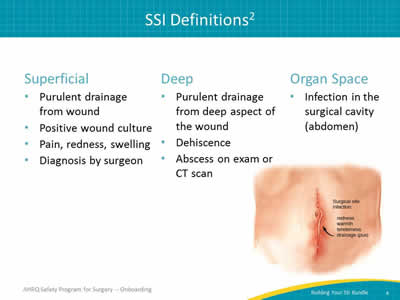

Slide 4: SSI Definitions

Say:

Let’s review definitions of wound infections. Standard definitions are on the Web site of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and on the Johns Hopkins Medicine Web site. Superficial wound infections are infections of the skin, seen with the naked eye and diagnosed when assessing a patient during a physical exam. For example, there’s purulent drainage from the wound, redness, and swelling, and wound cultures are positive for bacteria.

Deeper space infections are less common and trickier to diagnose. They’re on the deep aspect of the wound, at the level of the fascia, and are diagnosed with a computed tomography or CT scan.

And finally, organ-space infections are located in the surgical cavity. These can be abscesses that we drain in the surgical cavity with interventional radiology, surgery, or anastomotic leaks. Organ-space infections are the most complicated to treat, the most morbid, and the most expensive.

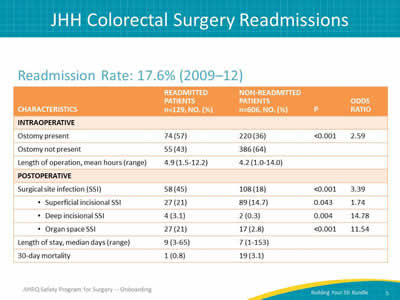

Slide 5: JHH Colorectal Surgery Readmissions

Say:

In colorectal surgery patients, we have a readmission problem. The readmission rate at Johns Hopkins Hospital is about 18 percent. The factor driving readmissions is complications, and specifically infections, so care of coordination or handoff from post-discharge to home aren’t going to help these problems. SSI prevention is going to help keep these patients from being readmitted.

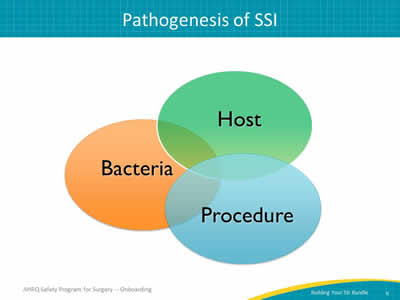

Slide 6: Pathogenesis of SSI

Say:

The pathogenesis of SSI is complicated. It reflects the interplay between the bacteria, the host, and the type of surgical procedure. For example, the colon is home to 100 trillion bacteria, especially gram-negative bacteria and anaerobes. This makes colon surgery much riskier for wound infections and other procedures.

Host risk factors include malnutrition, chemotherapy treatment, immunosuppressant medications, or steroids—all of which might weaken a patient’s immune system and make the patient more vulnerable to infection.

The type of procedure also influences a patient’s risk for wound infection. For example, infection risk differs whether a patient undergoes a rectal procedure or a colon procedure and whether an ostomy or stoma is involved.

Not surprisingly, there’s no one solution to preventing wound infection.

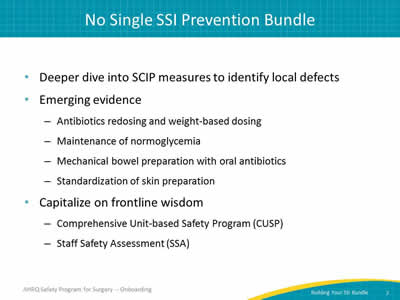

Slide 7: No Single SSI Prevention Bundle

Say:

Based on this complexity, there is likely no one checklist or bundle for SSI reduction. Also, many hospitals have spent enormous amounts of energy and resources toward improving performance on the Joint Commission’s Surgical Care Improvement Project, or SCIP, measures, and it doesn’t make sense to ask hospitals to re-examine areas they already do well.

So in this program, we’re asking teams to identify local opportunities to improve in one of three ways:

- In addition to SCIP measures, identify local defects that might contribute to SSI infection rates.

- Focus on some emerging evidence related to SSI reduction, including antibiotic redosing and weight-based dosing, maintenance of normoglycemia, the use of selected mechanical bowel prep with oral antibiotics, and standardization of the skin preparation.

- Mine the wisdom of frontline caregivers using the second step of the Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program or CUSP—to identify defects, for example, by using the Staff Safety Assessment, in which we ask staff, how do you think the next patient will be harmed, how will the patient develop a surgical-site infection, and what we can do to try to prevent that harm?

Slide 8: Deeper Dive Into SCIP Measures To Identify Local Defects

Say:

In this section, we will take a deeper dive into SCIP measures to identify local defects.

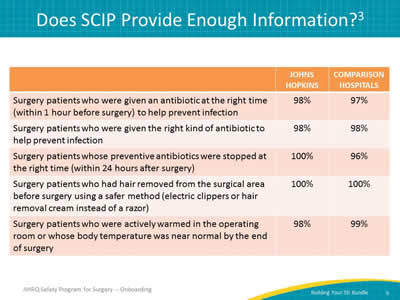

Slide 9: Does SCIP Give Us Enough Information?

Say:

Remember that for most hospitals, SCIP represents a random sample of patients undergoing colon surgery. For example, SCIP data usually represent only about 6 patients a month even though you may do about 30 to 40 colorectal operations a month.

Looking at Johns Hopkins as an example, you can see that based on Hospital Compare data, Johns Hopkins Hospital does quite well at giving the right antibiotic to the patient at the right time. Johns Hopkins also does quite well at discontinuing antibiotics. However, other domains relating to antibiotic use can be improved.

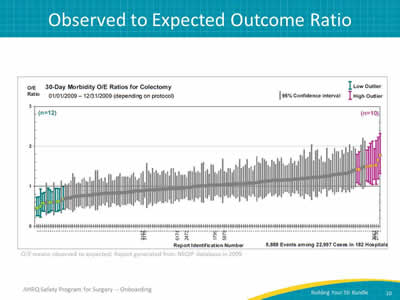

Slide 10: Observed to Expected Outcome Ratio

Say:

This chart shows the 30-day morbidity observed versus expected ratios for colectomy procedures from NSQIP in 2009.

Slide 11: Safety Issues & Improvement Opportunities

Say:

These are the results of the Staff Safety Assessment conducted when Hopkins first started this work. And you can see, defects with SCIP measures were identified that the quality control department hadn’t noted.

The front line said, we’re not always giving the antibiotics at the right time. Sometimes they’re getting administered very quickly or maybe right at the incision. The right antibiotic use is inconsistent, and we’re definitely not redosing them. They even questioned whether our temperature data were accurate. They frontline suspected the temperature probes didn't work properly, and that some kind of under-body warmer would be more appropriate. So, those are things the staff thought it had been working on as part of the SCIP measures, but the frontline indicated were not in place.

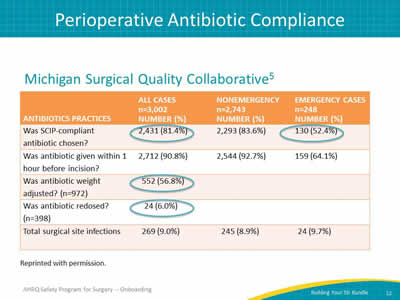

Slide 12: Perioperative Antibiotic Compliance

Say:

This slide shows data from the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative, which noticed only 80 percent of patients were receiving proper types of antibiotics. In emergency cases—where patients tend to be a high risk for complications like wound infections— only 50 percent of patients were getting the proper antibiotic.

You can see that weight-based dosing of cephalosporins and redosing were done even more rarely. We are going to talk about these later as “emerging evidence” to prevent SSIs.

So, even though there’s excellent level-one evidence to support the role of antibiotics in preventing wound infections, we have a long way to go, despite having worked on SCIP for so long.

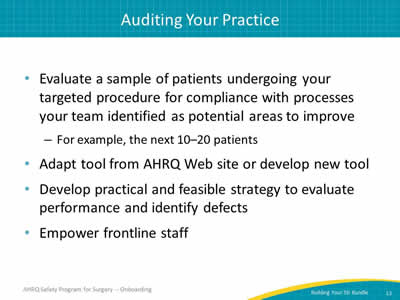

Slide 13: Auditing Your Practice

Say:

It can also help to start with small tests of change, for example evaluating 10–20 patients.

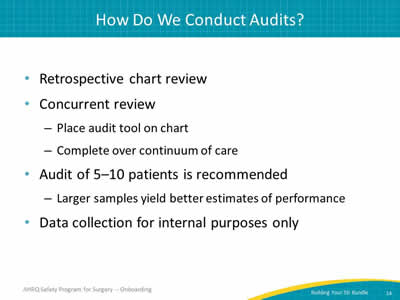

Slide 14: How Do We Conduct Audits?

Say:

Conducting audits involves several steps.

The first is to conduct a retrospective chart review on 5–10 patients. You will also want to conduct a concurrent review on an additional 5–10 patients. To conduct a concurrent review, place an audit tool in the chart and follow the audit over the continuum of care for each patient.

Auditing more than 5–10 patients will yield better estimates of performance.

These data do not need to be submitted. They are simply a benchmark for your team to use as you evaluate current progress.

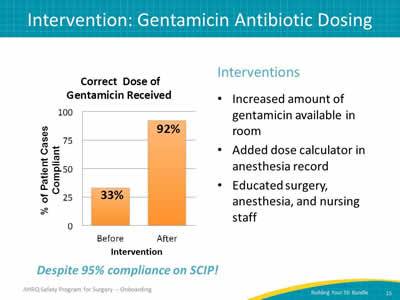

Slide 15: Intervention: Gentamicin Antibiotic Dosing

Say:

When the colorectal surgery CUSP team at Hopkins began to audit its practices, it found that patients weren’t always getting the right antibiotic, particularly if they were penicillin allergic. Partnering with a senior executive, the team implemented a variety of interventions once it understood what the barriers were. And as a result, now more than 90 percent of the time patients can count on getting the appropriate dose of gentamicin.

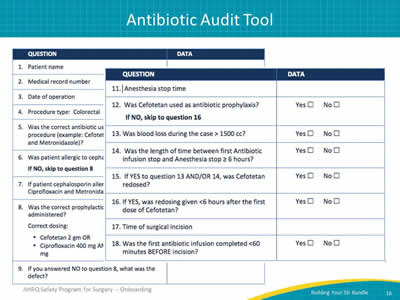

Slide 16: Antibiotic Audit Tool

Say:

This is the antibiotic audit tool. It has detailed questions related to best practices for antibiotic use. Using this tool will help identify defects that need to be addressed.

Slide 17: Intervention: Normothermia

Say:

Again, the team used an audit tool to better understand its performance. The team found that patients coming out of the operating room were at a temperature greater than 36 degrees Celsius only 80 percent of the time. The audit process provided an opportunity for the team to obtain a better understanding of performance barriers, tapping into the wisdom of frontline providers. Working with the team’s senior executive partner, the team was able to achieve desired temperatures in greater than 90 percent of patients.

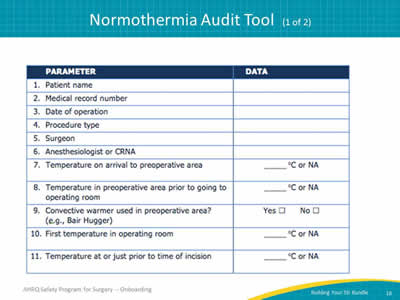

Slide 18: Normothermia Audit Tool

Say:

This is the temperature audit tool. It has detailed questions related to best practices for maintaining normothermia. Using this tool will help identify defects that need to be addressed.

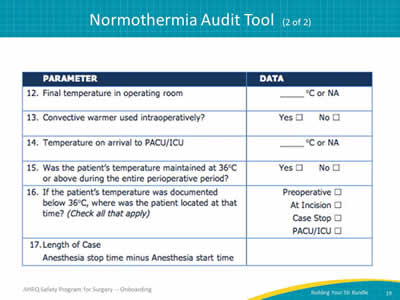

Slide 19: Normothermia Audit Tool

Say:

These are additional questions on the temperature audit tool.

Slide 20: Separation of Clean and Dirty Instruments

Say:

In some Hopkins colon infection meetings, staff members talk about implementing a closing set, or a separate instrument tray used when closing the fascia and the skin. But frontline staff didn’t agree. They wanted to build a separate set for anastomoses. Then during bowel operations, they would have a separate set of instruments to use and then dispose of. It was easier for staff to identify the exact point of the anastomosis than when the closing procedures began.

Also included are extra suctioning and change of gloves. These practices were self-audited and spread from general surgery to gynecological and pancreas surgeons, because they all operate on the bowel. And now it’s standard practice in the operating room, despite no evidence to support it. Based on input from all operating room providers, it was felt to be the best practice.

Slide 21: Bringing Emerging Evidence for SSI Prevention to Your Patients

Say:

In this section we will review emerging evidence for SSI prevention. This evidence is not a SCIP requirement, but has reasonable evidence to support adding it to your SSI bundles.

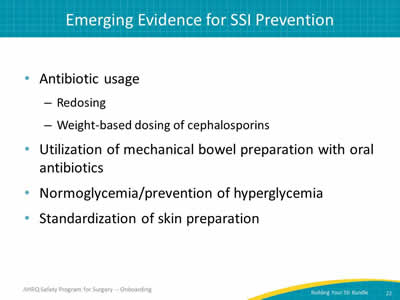

Slide 22: Emerging Evidence for SSI Prevention

Say:

First, related to antibiotic usage in these new guidelines, the evidence suggests redosing antibiotics for cases that are longer than 4 hours, depending on your timeline. Also, regarding weight-based dosing for cephalosporins, the guidelines focus on weight-based dosing for cefazolin. Some hospitals have extended that to include weight-based dosing for cefotetan, with larger patients receiving 3 milligrams/kg of cefotetan. Also, the guidelines advocate the use of mechanical bowel preparation with oral antibiotics for colon surgery. Again, a group of national societies have endorsed this practice, so it helps to achieve staff buy-in and consider these interventions.

There also is emerging evidence for maintenance of normoglycemia or prevention of hyperglycemia in the perioperative period. And finally, evidence is emerging to support standardization of skin preparation with a dual-agent preparation solution that includes alcohol.

Slide 23: Emerging Literature Excerpt

Say:

These are the new antimicrobial guidelines from the American Society of Health-System pharmacists, or ASHP. They cover all types of surgeries, so there are recommendations for every type of surgery, but they provide a table that describes different procedures, including colon surgery.

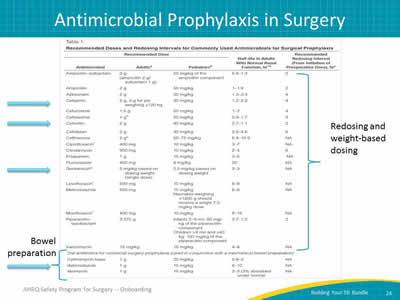

Slide 24: Antimicrobial Prophylaxis in Surgery

Say:

This is the table, and it indicates whether weight-based dosing is recommended, and at the bottom of the page, bowel preparation recommendations are shown.

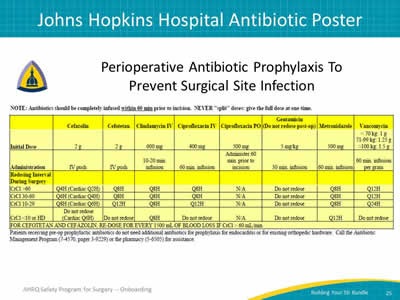

Slide 25: Johns Hopkins Hospital Antibiotic Poster

Say:

This is an example of a way to make a standard antibiotics protocol for your hospital. The infection control department at Johns Hopkins has taken these recommendations and selected standard antibiotics for different procedures. The selections were based on the culture evaluations and sensitivity of different bacteria from wound infections. So, for example, for colon surgery, cefotetan is used.

But this is the first step to developing a standard algorithm of what antibiotic to use for each procedure to eliminate some variability. With a standard procedure, you’re less likely to underdose or use an inappropriate antibiotic.

Redosing is also something to consider if you’re not already doing it. The goal is to maintain therapeutic levels throughout the entire case. However, the new guidelines recommend redosing cefoxitin every 2 hours, so it might be unreasonable. If you use cefoxitin, consider changing to another antibiotic.

Hospitals frequently implement policies and mandates, but we don’t always recognize our actual practice. Audit 15–20 patients to determine if your longer-case patients were redosed, whether weight-based dosing was done, and where there was room for improvement. Share the audit reports with the front line—that’s how you engage people. By sharing the data trends and defects, you allow frontline providers to own the results. That is how you change the culture and get the buy-in required for system success.

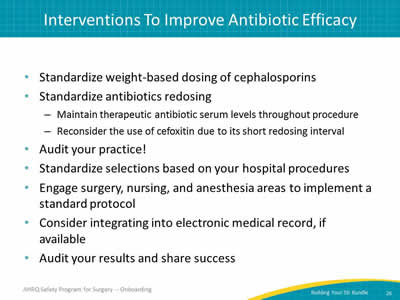

Slide 26: Interventions To Improve Antibiotic Efficacy

Say:

We know it’s important to maintain antibiotic serum levels during the entire procedure. What we’re learning is that antibiotic serum levels do not last as long as we thought they did. New guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America, or IDSA, recommend redosing at shorter intervals. For example, previous guidelines recommended redosing cefotetan as routine prophylaxis for colon surgery at 8-hour intervals. The new guides recommend every 6 hours.

Similarly, IDSA recommends redosing cefazolin every 3 hours and cefoxitin every 2 hours.

Cefoxitin is a SCIP-approved antibiotic for colon prophylaxis. But the new guidelines indicate this might not be the best choice. Most colon operations are more than 2 hours, so if you use cefoxitin you would need to redose in almost every case. Your hospital may consider selecting an antibiotic that’s longer acting.

Also included in these guidelines are weight-based dosing of cephalosporin. Especially if you use cefazolin and Flagyl, you should consider increasing the dose of cefazolin to 3 mg for larger patients. Your safety program team can focus on this issue as it requires system changes and education for multiple disciplines.

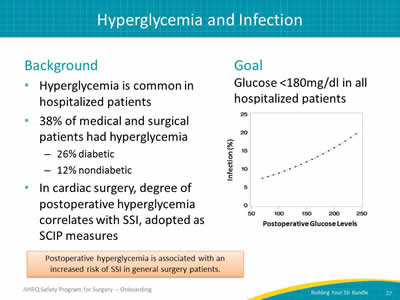

Slide 27: Hypoglycemia and Infection

Say:

Maintaining normoglycemia can reduce risk for wound infection. Hyperglycemia is common in hospitalized patients, even patients who are not diabetic.

In cardiac surgery patients, it’s documented that hyperglycemia correlates with the rate of wound infection, and this is a SCIP measure in this patient population. Smaller studies of general surgery patients also support a correlation between postoperative glucose levels and infection.

The Association of Endocrinologists recommends that all hospitalized patients maintain a glucose level less than 180 mg/dL. We believe that achieving this goal will also help to reduce SSIs. Maintaining normoglycemia is complex, requires coordination between multiple disciplines, and spans the continuum of care from the preoperative clinic to the OR to the ward. It requires proactive interventions because frequently in patients with diabetes, the first glucose on the day of surgery is 160, and then next time it is checked in the OR it is 220. We need to have a plan. Talk to your endocrinologists to see if you have an insulin drip protocol or other tools that might be helpful to implement this best practice.

Slide 28: University of Washington/Glucose Control

Say:

This is one example from the University of Washington of a glucose-control pathway or algorithm for the operating room.

Slide 29: Could You Improve Glycemic Management?

Say:

Are you doing as well as you can on glycemic management? Your SUSP team can audit your current practice. You can pick just that post-op day one glucose and just check all those post-op day one glucoses on 20 patients. You can look at patients with diabetes—does your hospital have a policy? Do you check glucose levels of patients with diabetes in the prep area? Do patients get checked beforehand when they go to a pre-anesthesia clinic? What are the policies, and what do you do to address defects?

This needs to be a multidisciplinary approach. Incorporate the endocrinology department, as well as surgical and nursing providers. Developing a protocol extends to all points of patient care: from the preoperative areas, through the operating rooms, and to the floor rooms.

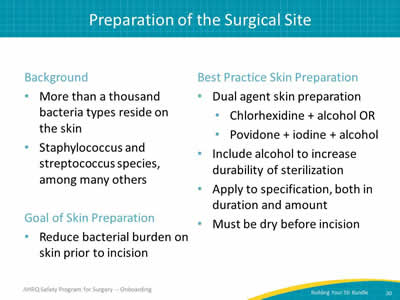

Slide 30: Preparation of the Surgical Site

Say:

The next area of emerging evidence relates to preparation of the surgical site. We know the skin can harbor thousands of types of bacteria, mostly staph and strep species. The colon harbors more than 100 trillion bacteria with more anaerobes and gram-negative bacteria. A good skin preparation is the best way to address the former.

Based on the evidence, current best practice is to use dual-agent prep, a preparation that includes chlorhexidine and alcohol (ChloraPrep) or povidone-iodine and alcohol (DuraPrep). Both preparations have specific instructions for proper use. Even if your hospital is using one of these, the technique for application may not be correct. Considering auditing your practice and identifying areas for improvement. Remember to allow solutions with alcohol time to dry.

You can monitor progress in skin prep by reviewing the cultures from your wound infections with your infection control practitioner. You can see if you have a lot of colon superficial infections with staph and strep. If you improve your skin prep, it is likely that this will not happen.

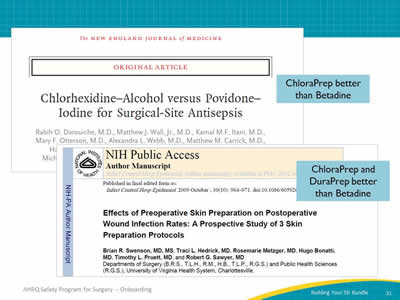

Slide 31: Literature Excerpts

Say:

The best practice uses dual-agent skin preparation, chlorhexidine plus alcohol or povidone-iodine plus alcohol, so either ChloraPrep or DuraPrep. The goal of the skin preparation is to increase the durability of the sterilization. For the sterilization to last, you need to administer these products as directed, including the appropriate area of skin to cover. In addition, any alcohol-based solution must be dry before the incision.

Standardize this process throughout the operating room. For example, when we transitioned to ChloraPrep, the ChloraPrep representative trained all surgical staff. We then required individual confirmation of the training before they started the new preparation product. Two papers support the dual-agent preparations. One is the 2009 ChloraPrep paper from the New England Journal of Medicine, which showed that ChloraPrep yielded better results than Betadine. The other paper from the University of Virginia showed that ChloraPrep and DuraPrep also exceeded Betadine results.

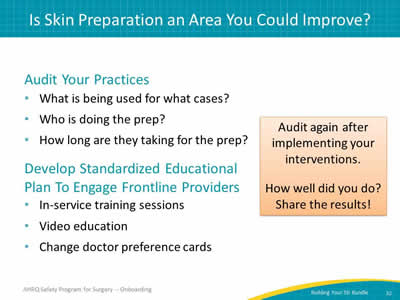

Slide 32: Is Skin Prep an Area You Could Improve?

Say:

You need to audit your practices. A quality outcomes representative, an administrative representative, or a frontline staff member in your hospital can audit your practices. Look at the beginning of the case, see who’s doing the skin preparation.

Ask:

Did the ChloraPrep skin preparation take the full 3 minutes?

Was the application area allowed to dry?

Say:

You can develop an audit tool to keep track of that and then share the data and devise an educational plan for standardizing who will be held accountable for it through, for example, in-service training and video education.

And then keep auditing and see if you’ve demonstrated improvement or changes in practice.

Slide 33: Key Takeaways

Say:

In summary, there is not a single SSI prevention bundle that will work for every surgical line at every hospital. Each clinical area will have problems with different things at different times. Emphasize local defects with the Staff Safety Assessment, because asking the frontline staff is key.

Audits will also help identify defects and gaps between protocols and reality in care delivery. Auditing is an iterative process—once you create your bundle, it may not be consistent for every patient until you work through the system, audit your practice, continue educating, and actually hardwire those processes into your system.

Any tools should be adapted to your local environment. They provide starting points. The CUSP method is going to empower the front line to be part of this. Frontline staff will share with you why your bundle isn’t working, for instance, why a patient didn’t receive an element of your bundle, or what still needs improvement. With the feedback of your frontline staff you will start to see great improvement.

Slide 34: Action Items

Say:

Some recommended action items include—

- Review your staff safety assessment results with your frontline staff.

- Pick two or three audit tools and use them to audit 5 to 10 patients.

- Create a performance goal for each intervention.

- Develop your SSI bundle.

- Develop system changes to implement interventions.

- Share your experiences with your peers both within your health care organization.

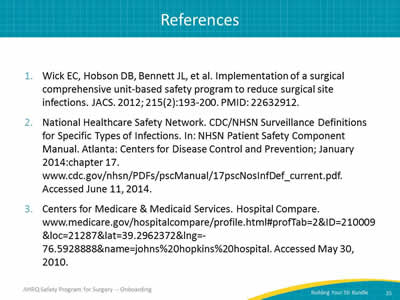

Slide 35: References

Slide 36: References