Building Your SSI Prevention Bundle: Slide Presentation

AHRQ Safety Program for Surgery

Slide 1: AHRQ Safety Program for Surgery—Onboarding

Building Your SSI Prevention Bundle

Slide 2: Learning Objectives

After this session, you will be able to–

- Develop and implement a surgical site infection (SSI) reduction goal and prevention bundle that addresses up to three surgical care processes.

- Build a bundle based on the results of your staff safety assessment.

- Review how to initiate audits of your processes.

- Create a team performance goal (improvement in outcome).

- Proceed with improvements without strong evidence base.

- Locate AHRQ Safety Program for Surgery resources on the project Web site.

Slide 3: Background1

Surgical Site Infections–

- Are the most common nosocomial infections in the surgical patient.

- Are the most common colorectal abdominal surgery complications (3-30%).

- Are associated with increased length of stay, readmission, and mortality.

- Cost, depending on infection location, $6,200—$15,000 per patient (superficial vs. organ space).

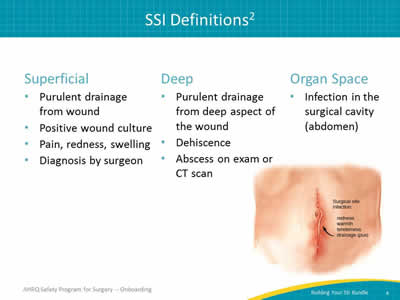

Slide 4: SSI Definitions2

Superficial

- Purulent drainage from wound.

- Positive wound culture.

- Pain, redness, swelling.

- Diagnosis by surgeon.

Deep

- Purulent drainage from deep aspect of the wound.

- Dehiscence.

- Abscess on exam or CT scan.

Organ Space

- Infection in the surgical cavity (abdomen).

Image: Drawing of a surgical site infection. A vertical incision with small stitches shows signs of redness, warmth, tenderness and drainage (pus).

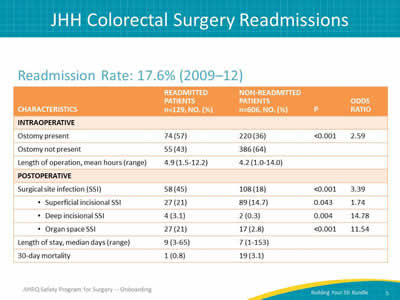

Slide 5: JHH Colorectal Surgery Readmissions

Readmission Rate: 17.6% (2009–12)

Image: Table depicting readmission rates in 2009-2012 Columns are labeled Characteristics, readmitted patients, non-readmitted patients, p value, odds ratio. The rows are labeled intraoperative: ostomy present or ostomy not present; length of operation, mean hours. Postoperative surgical site infection (superficial incisional SSI, deep incisional SSI, organ space SSI), length of stay, 30-day mortality.

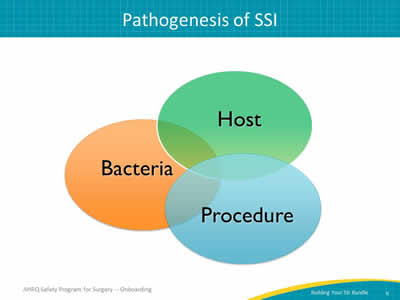

Slide 6: Pathogenesis of SSI

Image: Venn diagram illustrating interplay between bacteria, host, and procedure interactions, which can contribute to surgical site infections. Each component is shown as a separate but overlapping circle.

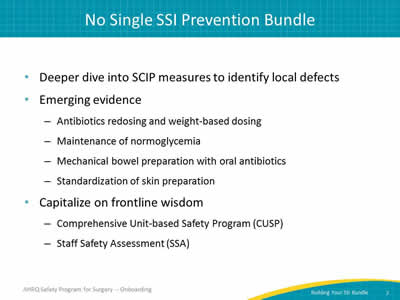

Slide 7: No Single SSI Prevention Bundle

- Deeper dive into SCIP measures to identify local defects.

- Emerging evidence:

- Antibiotics redosing and weight-based dosing.

- Maintenance of normoglycemia.

- Mechanical bowel preparation with oral antibiotics.

- Standardization of skin preparation.

- Capitalize on frontline wisdom:

- Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program (CUSP).

- Staff Safety Assessment (SSA).

Slide 8: Deeper Dive into SCIP Measures to Identify Local Defects

Deeper Dive into SCIP Measures to Identify Local Defects

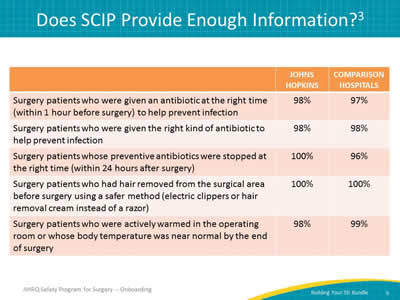

Slide 9: Does SCIP Provide Enough Information?3

Image: Table compares Johns Hopkins (JH) and Comparison Hospitals (Other):

- Surgery patients who were given an antibiotic at the right time (within 1 hour before surgery) to help prevent infection; JH - 98%, Other - 97%.

- Surgery patients who were given the right kind of antibiotic to help prevent infection; JH - 98%, Other - 98%.

- Surgery patients whose preventive antibiotics were stopped at the right time (within 24 hours after surgery); JH - 100%, Other - 96%.

- Surgery patients who had hair removed from the surgical area before surgery using a safer method (electric clippers or hair removal cream instead of a razor); JH - 100%, Other - 100%.

- Surgery patients who were actively warmed in the operating room or whose body temperature was near normal by the end of surgery; JH - 98%, Other - 99%.

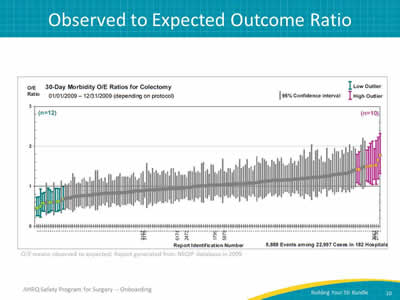

Slide 10: Observed to Expected Outcome Ratio

Image: Graph depicting NSQIP report 2009; 30 day morbidity observed to expected (o/e) ratios for colectomy. The X-axis is labeled with report identification numbers. The Y-axis is a range of 0 to 3. This graph is an unpublished report from the NSQIP database in 2009.

Sample 2009 NSQIP report (American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program).

Slide 11: Safety Issues & Improvement Opportunities4

Image: Table with two columns. The first column shows applying CUSP Step 2 to identify safety issues. Rows beneath this column show examples of different types of safety issues. The second column shows applying CUSP steps 4 and 5 with opportunities to improve. Rows beneath this column list opportunities to improve related to the categories of safety issues identified.

Reference: Wick EC, Hobson D, Bennett J, Demski R, Maragakis L, Gearhart SL, et al. Implementation of a Surgical Comprehensive Unit Based Safety Program (CUSP) to Reduce Surgical Site infections. J. Am Coll Surg 2012; 215(2):193-200. PMID: 22632912.

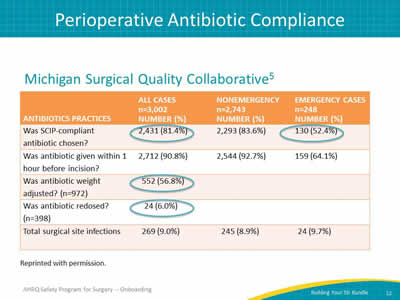

Slide 12: Perioperative Antibiotic Compliance

Image: Table shows data from the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative.5 The table includes four columns. The first column titled Antibiotics Practices includes rows that describe different antibiotic practices. Column 2 shows the numbers of cases in which a particular practice identified in column 1 was applied. Column 3 shows the number of nonemergency cases in which the practice identified in column 1 was applied. Column 4 shows the number of emergency cases in which the practice identified in column 1 was applied. The number of cases and emergency cases for some different practices are highlighted. A SCIP-compliant antibiotic was chosen in 2,431 or 81.4% of cases (n=3002). It was chosen in 130 or 52.4% of emergency cases. Antibiotics were weight-adjusted in 552 or 56.8% of cases (n=972). Antibiotics were redosed in 24 or 6% of cases (n=3002).

Reference: Hendren et al. Am. J Surg 2011.

Slide 13: Auditing Your Practice

- Evaluate a sample of patients undergoing your targeted procedure for compliance with processes your team identified as potential areas to improve.

- For example, the next 10–20 patients.

- Adapt tool from AHRQ Web site or develop new tool.

- Develop practical and feasible strategy to evaluate performance and identify defects.

- Empower frontline staff.

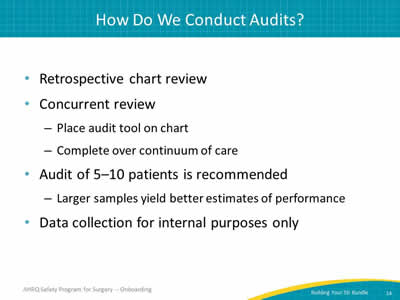

Slide 14: How Do We Conduct Audits?

- Retrospective chart review.

- Concurrent review:

- Place audit tool on chart.

- Complete over continuum of care.

- Audit of 5–10 patients is recommended:

- Larger samples yield better estimates of performance.

- Data collection for internal purposes only.

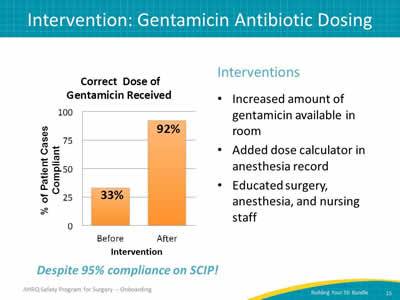

Slide 15: Intervention: Gentamicin Antibiotic Dosing

Interventions

- Increased amount of gentamicin available in room.

- Added dose calculator in anesthesia record.

- Educated surgery, anesthesia, and nursing staff.

Despite 95% compliance on SCIP!

Image: Bar chart highlighting the percentage of patients receiving the correct dose of gentamicin before and after intervention. Before the intervention, only 33% of patients received the correct dose of gentamicin, despite 95% compliance on SCIP measures. After the intervention, 92% of patients received the correct, evidence-based dosing of gentamicin.

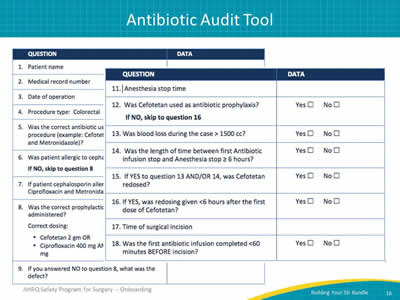

Slide 16: Antibiotic Audit Tool

Image: Example Antibiotic Audit tool with two columns: the first is labeled "Questions" and the second is labeled "Data." The data column has space provided for fill-in responses, yes/no checkboxes, or drug, dose and time details.

- Patient name.

- Medical record number.

- Date of operation.

- Procedure Type: Colorectal.

- Was the correct antibiotic used, based on the procedure (example: Cefotetan OR Ciprofloxacin and Metronidazole)?

- Was patient allergic to cephalosporins? If NO, skip to question 8

- If patient cephalosporin allergic, were both Ciprofloxacin and Metronidazole given?

- Was the correct prophylactic antibiotic dose administered? Correct dosing:

- Cefotetan 2 gm OR

- Ciprofloxacin 400 mg AND

- Metronidazole 500 mg

- If you answered NO to question 8, what was the defect?

- Antibiotic infusion stop time.

- Anesthesia stop time.

- Was Cefotetan used as antibiotic prophylaxis? If NO, skip to question 16.

- Was blood loss during the case >1500 cc?

- Was the length of time between first Antibiotic infusion stop and Anesthesia stop ≥6 hours?

- If YES to question 13 AND/OR 14, was Cefotetan redosed?

- If YES, was redosing given < 6 hours after the first dose of Cefotetan?

- Time of surgical incision?

- Was the first antibiotic infusion completed < 60 minutes BEFORE incision?

Slide 17: Intervention: Normothermia

Interventions

- Confirmed that temperature probes were accurate first:

- Needed surgeons to accept temperature data.

- Compared indwelling urinary catheter and esophageal sensors in local trial.

- Initiated forced air warming intervention in the pre-operative area after temperature accuracy established.

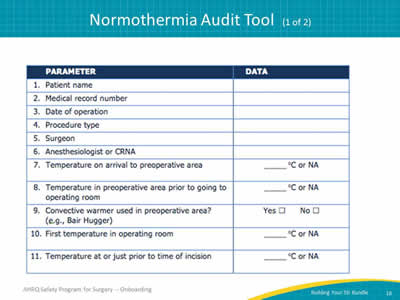

Slide 18: Normothermia Audit Tool

Image: Sample of Normothermia Audit Tool (1 of 2). Table lists the following parameters:

- Patient name.

- Medical record number.

- Date of operation.

- Procedure.

- Surgeon.

- Anesthesiologist or CRNA.

- Temperature (°C) on arrival to preoperative area.

- Temperature (°C) in preoperative area prior to going to operating room.

- Convective warmer used in preoperative area? (i.e., Bair Hugger)

- First temperature (°C) in operating room.

- Temperature (°C) at or just prior to time of incision.

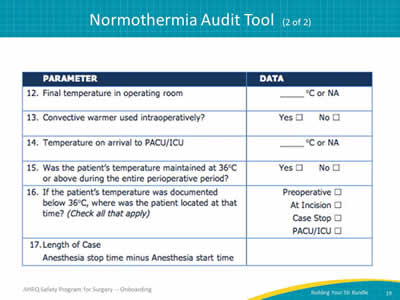

Slide 19: Normothermia Audit Tool

Image: Sample of Normothermia Audit Tool (2 of 2). Table lists the following parameters:

- Final temperature (°C) in the operating room.

- Convective warmer used intra-operatively?

- Patient temperature (°C) on arrival to PACU/ICU.

- Was the patient’s temperature maintained at 36°C or above during the entire perioperative period?

- If the patient’s temperature was documented below 36°C, where was the patient located at that time? [pre-op, at incision, case stop, PACU/ICU]

- Length of Case (Anesthesia start to stop time)

Slide 20: Separation of Clean and Dirty Instruments

Interventions

- Separate tray of instruments used for bowel anastomosis.

- Extra suction along with both bovie tip and gloves opened and changed after anastomosis.

- Educational sessions with scrub techs and nurses about instrument separation.

- Real-time audits.

Images: Clean surgical instruments on a sterile table. Along with the next image of used instruments, this image shows the physical separation between used and unused surgery implements. Instruments used in surgery stored in a separate bowl marked "dirty." Along with the preceding image of sterile instruments, this image shows the physical separation between used and unused surgery implements.

Slide 21: Bringing Emerging Evidence for SSI Prevention to your Patients

Bringing Emerging Evidence for SSI Prevention to your Patients

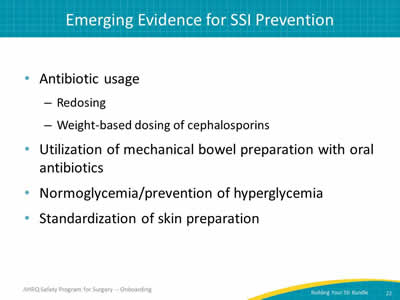

Slide 22: Emerging Evidence for SSI Prevention

- Antibiotic usage:

- Redosing.

- Weight-based dosing of cephalosporins.

- Utilization of mechanical bowel preparation with oral antibiotics.

- Normoglycemia/prevention of hyperglycemia.

- Standardization of skin preparation.

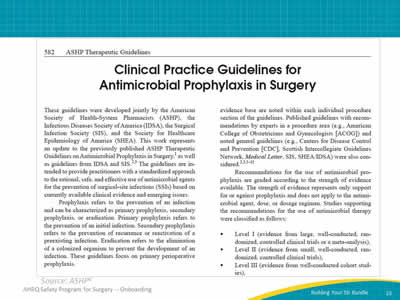

Slide 23: Emerging Literature Excerpt

Image: Screenshot of an ASHP article entitled “Clinical Practice Guidelines for Antimicrobial Prophylaxis in Surgery.”

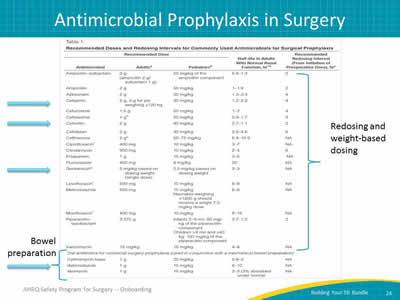

Slide 24: Antimicrobial Prophylaxis in Surgery

Image: A table depicting recommended doses and redosing intervals for commonly used antimicrobials for surgery prophylaxis for adults and pediatrics.

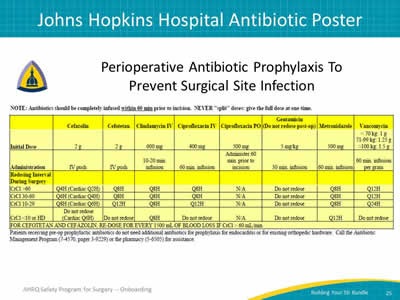

Slide 25: Johns Hopkins Hospital Antibiotic Poster

Image: A table depicting perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent surgical site infection.

Slide 26: Interventions To Improve Antibiotic Efficacy

- Standardize weight-based dosing of cephalosporins.

- Standardize antibiotics redosing:

- Maintain therapeutic antibiotic serum levels throughout procedure.

- Reconsider the use of cefoxitin due to its short redosing interval.

- Audit your practice!

- Standardize selections based on your hospital procedures.

- Engage surgery, nursing, and anesthesia areas to implement a standard protocol.

- Consider integrating into electronic medical records.

- Audit your results and share success.

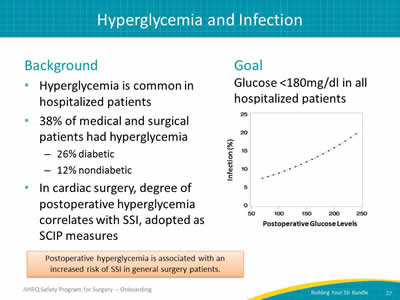

Slide 27: Hypoglycemia and Infection

Background

- Hyperglycemia is common in hospitalized patients.

- 38% of medical and surgical patients had hyperglycemia.

- 26% diabetic.

- 12% nondiabetic.

- In cardiac surgery, degree of post-operative hyperglycemia correlates with SSI, adopted as SCIP measures.

Goal

- Glucose <180mg/dl in all hospitalized patients.

Postoperative hyperglycemia is associated with an increased risk of SSI in general surgery patients.

Image: Line graph shows the correlation between infection rate and Post-Op Glucose levels. Post-operative hyperglycemia is associated with increased risk of SSI in general surgery patients.

Reference: Ramos, et al. 2008.

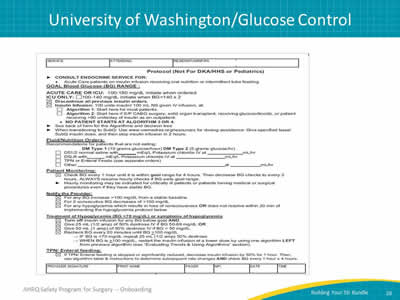

Slide 28: University of Washington/Glucose Control

Image: A glucose-auditing tool used by the University of Washington.

Slide 29: Could You Improve Glycemic Management?

- Audit your current practice.

- Do you have a policy?

- Consider gathering a multidisciplinary team to develop a protocol for your hospital:

- Endocrinology.

- Surgery.

- Anesthesiology.

- Nursing (ward and preoperative).

Slide 30: Preparation of the Surgical Site

Background

- More than a thousand bacteria types reside on the skin.

- Staphylococcus and streptococcus species, among many others.

Goal of skin preparation

- Reduce bacterial burden on skin prior to incision.

Best practice skin preparation

- Dual agent skin preparation:

- Chlorhexidine + alcohol OR

- Povidone + iodine + alcohol

- Include alcohol to increase durability of sterilization.

- Apply to specification, both in duration and amount.

- Must be dry before incision.

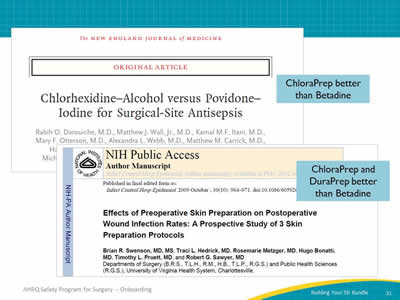

Slide 31: Literature Excerpts

Images: An image of a journal article from the New England Journal of Medicine. An image of a journal article from Infection Control Hospital Epidemiology. Text notes next to each article read "ChloraPrep better than Betadine" and "ChloraPrep and DuraPrep better than Betadine."

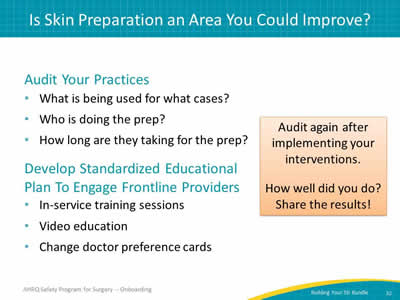

Slide 32: Is Skin Prep an Area You Could Improve?

Audit your practices

- What is being used for what cases?

- Who is doing the prep?

- How long are they taking for the prep?

Develop standardized educational plan for frontline providers

- In-service training sessions.

- Video education.

- Change doctor preference cards.

Audit again after implementing your interventions.

How well did you do? Share the results!

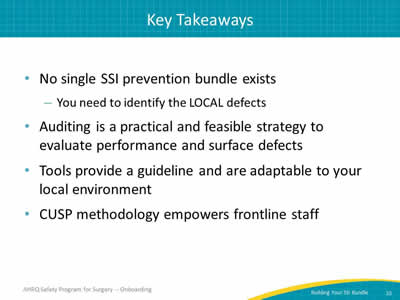

Slide 33: Key Takeaways

- No single SSI prevention bundle exists.

- You need to identify the LOCAL defects.

- Auditing is a practical and feasible strategy to evaluate performance and identify defects.

- Tools provide a guideline and are adaptable to your local environment.

- CUSP methodology empowers frontline staff.

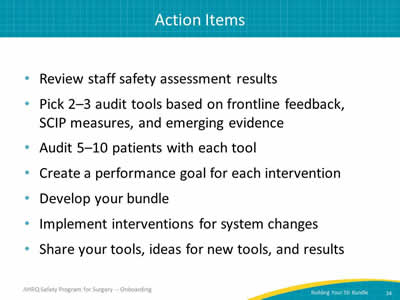

Slide 34: Action Items

- Review staff safety assessment results.

- Pick 2–3 audit tools based on frontline feedback, SCIP measures and emerging evidence.

- Audit 5–10 patients with each tool.

- Create a performance goal for each intervention.

- Develop your bundle.

- Implement interventions for system changes.

- Share your tools, ideas for new tools, and results.

Slide 35: References

- Wick EC, Hobson DB, Bennett JL, et al. Implementation of a surgical comprehensive unit-based safety program to reduce surgical site infections. JACS 2012; 215(2):193-200. PMID: 22632912.

- National Healthcare Safety Network. CDC/NSHN Surveillance definitions for specific types of infections. In: NSHN Patient Safety Component Manual. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; January 2014:chapter 17. www.cdc.gov/nhsn/PDFs/pscManual/17pscNosInfDef_current.pdf. Accessed June 11, 2014.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Hospital Compare. www.medicare.gov/hospitalcompareprofile.html#profTab=2&ID=210009&loc=21287&lat=39.2962372&lng=-76.5928888&name=johns%20hopkins%20hospital. Accessed May 30, 2010.

Slide 36: References

- Johns Hopkins Medicine, Health Library. Surgical Site Infections.http://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/healthlibrary/conditions/surgical_care/surgical_site_infections_134,144/ Accessed September 14, 2014.

- Hendren S, Englesbe MJ, Brooks L, et al. Prophylactic antibiotic practices for colectomy in Michigan. Am J Surg 2011;201(3):290-293. PMID: 21367365.

- American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Clinical practice guidelines for antimicrobial prophylaxis in surgery. www.ashp.org/surgical-guidelines. Accessed September 14, 2014. doi:10.2146/ajhp120568. Also note: Bratzler DW, Dellinger EP, Olsen KM, et al. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 2013 Feb 1;70(3): 195-283,582. PMID:23327981.