Program Overview: Facilitator Notes

AHRQ Safety Program for Surgery

Slide 1: Program Overview

Say:

You have embarked on a unique journey.

Slide 2: Mead Quotation

Say:

Margaret Mead was a popular and sometimes controversial cultural anthropologist in the ’60s and ’70s. This statement still resonates, particularly now in health care, because of the changing environment, and the constant pressures to do more for less. It is sometimes hard to see the big picture and appreciate the impact each of us has in improving patient outcomes.

Margaret Mead said, “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.”

And in health care today, this feeling of not being part of something larger or understanding why the work we do is so meaningful can wear on us. So please accept our acknowledgement and recognition for the work you are doing toward improving patient safety.

These types of efforts and ultimately our frontline staff are the only ways to make significant improvements toward patient safety.

Without a doubt that work will be hard. It is hard to dedicate time and resources, and until our organizations decide to truly invest in the power of frontline staff and create that infrastructure, it will remain difficult.

It will take work, and it will take new work—work on the Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program, or CUSP, is new to many organizations. With this project you can focus your attention and augment your tools with ideas to jumpstart your efforts to improve care for surgical patients.

Slide 3: Learning Objectives

Say:

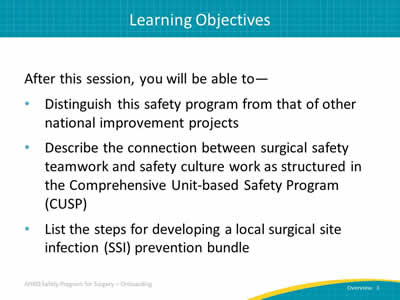

From a high level, this presentation will cover the following topics.

You will be able to distinguish the AHRQ Safety Program for Surgery from that of other national improvement projects.

The connection between surgical safety teamwork and safety culture work as structured in CUSP will be clear.

You will also be familiar and hopefully able to list the steps for developing a local surgical site infection, or SSI, prevention bundle.

Slide 4: Why is This Work Important?

Say:

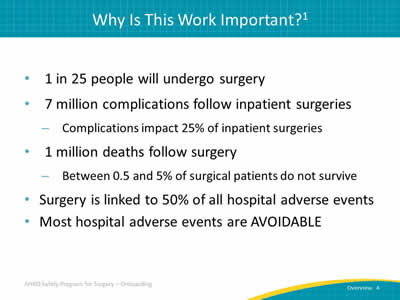

For many patients, surgical care is a risky endeavor. Estimates suggest that 25 percent of patients undergoing inpatient surgeries develop complications, and these complications prolong hospital stays, lead to unnecessary readmissions, and can take their lives. Often, we hear that these complications, readmissions, and deaths are inevitable—our patients are old, our patients are sick—yet at least half of these adverse surgical events are preventable, and they take an immeasurable toll on our patients and their families.

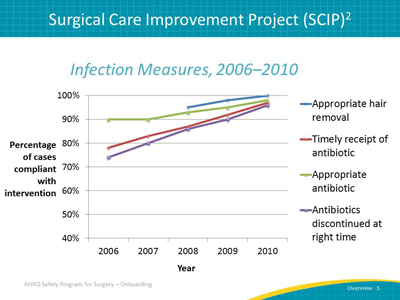

Slide 5: Surgical Care Improvement Project

Say:

Nationwide, we have made remarkable progress in specific measures to improve surgical care and reduce surgical-site infection, like giving the right antibiotic at the right time or clipping the skin as opposed to shaving the skin prior to a surgical incision as part of the Surgical Care Improvement Project, or SCIP. Yet, for the most part, these improvements have not translated into reduced infection rates or to improved outcomes.

Ask:

Why might that be?

Say:

There are at least two important reasons. First, surgical site infections are exceedingly complex, and there are likely many defects, in addition to the SCIP measures, that come into play. For example, preventing surgical site infections is not just about giving the right antibiotic at the right time, but also about making sure patients receive the right dose of antibiotic and/or that those antibiotics are appropriately redosed. Similarly, we need to go beyond asking whether skin was shaved. Are we using the right agent for skin prep? Is the quality of skin prep appropriate to prevent surgical site infections?

The second reason these improvements have likely not translated into improved outcomes is that, for many hospitals, SCIP has become an exercise in “checking the box.” We often align our documentation, for example, to meet SCIP criteria. But for these improvement efforts to be successful, it takes much more than checking boxes. Our frontline staff needs to be engaged and to find value in their work. Until our staff is engaged rather than simply compliant when it comes to checking boxes, our patients are unlikely to see better outcomes despite our continued focus on SCIP measures.

Note:

Appropriate hair removal – Surgery patients needing hair removed from the surgical area before surgery, who had hair removed using a safer method (electric clippers or hair removal cream – not a razor

Timely receipt of antibiotic – Surgery patients who were given an antibiotic at the right time (within 1 hour before surgery) to help prevent infection.

Slide 6: What is the AHRQ Safety Program for Surgery?

Say:

This Safety Program for Surgery is funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, or AHRQ.

It is a national improvement effort designed to reduce SSIs and other surgical complications through CUSP.

Participation is open to individual hospitals of all sizes in the United States through mid-2015.

Surgical complications take an immeasurable toll on our patients and their families. By participating in this safety program, you are part of the solution.

Slide 7: What is the AHRQ Safety Program for Surgery?

Say:

In contrast to the mature evidence for preventing central line-associated bloodstream infections or ventilator-associated pneumonia, there likely is no single way to prevent SSIs. The defects leading to SSIs vary widely across different organizations. We also recognize that many hospitals have already spent significant energy and resources and may already be successful in some areas. It doesn’t make sense to ask hospitals to refocus on areas where they are doing well. In this program, we’ll learn about hospitals that are doing well and that take three different approaches to identify their local defects. Each participating team will be asked to participate in all three approaches.

First, dive deep into SCIP measures to identify opportunities for improvement by auditing or collecting a time-limited amount of data. For example, in addition to evaluating if patients are getting the right antibiotics at the right time as guided by SCIP, are we giving the right dose and appropriately redosing?

Second, we will focus on emerging evidence like selective use of bowel preps for colon surgery, antibiotic redosing, and use of ChloraPrep skin antiseptic for skin prep.

Most of the interventions though, will come from the third approach.

Ask:

Simply ask your frontline staff:

- How they think the next patient will be harmed,

- Why they will develop an SSI, and

- What they think we can do to prevent these complications.

Say:

The reality is that our frontline staff members have tremendous wisdom. Use it. They already know how patients will be harmed because they defend against harm every day.

We need to learn how to embed this challenging adaptive work into local practice to help ensure our staff members find value in the work they do.

Slide 8: Safety Program Leverages National Leaders

Say:

This project developed through partnerships with many world-renowned organizations to deliver cutting-edge patient safety initiatives. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality funded the project administered by Johns Hopkins Medicine’s Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality, American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program, World Health Organization, and social science experts at the University of Pennsylvania.

Slide 9: Our Shared Project Goals

Say:

The goals of the safety program are–

- To decrease surgical-site infections and other complications, like venous thromboembolism, pneumonia, and readmissions, because these complications are a major driver for readmissions.

- To achieve significant improvements in safety culture as measured by the AHRQ HSOPS survey, or Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture.

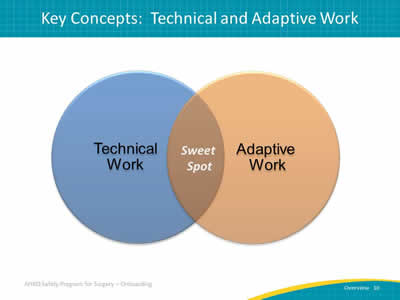

Slide 10: Key Concepts: Technical and Adaptive Work

Say:

The model we will use in this program builds on existing literature and includes two components, technical work and adaptive work.

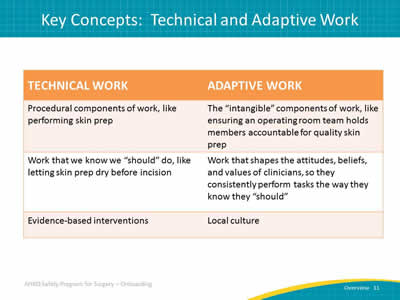

Slide 11: Key Concepts: Technical and Adaptive Work

Say:

Technical work is the long list of evidence-based practice and includes interventions we know we should do to prevent complications, such as giving the right antibiotic at the right time and appropriately prepping the skin prior to incision. Many organizations have worked for years to standardize care and incorporate these interventions into local policies, protocols, and checklists to help ensure patients receive the right therapies. These checklists are helpful tools, but they only work if the staff is engaged to use them.

Adaptive work is the “intangible” components of work, like ensuring OR team members hold each other accountable for quality skin prep. Adaptive work addresses the attitudes, beliefs, and values of clinicians that drive behaviors, norms, and processes within our organizations and ORs. Addressing adaptive concerns tends to provide many challenges, but it is the only way to improve teamwork and safety culture. Checklists can only be effective if they are actually used.

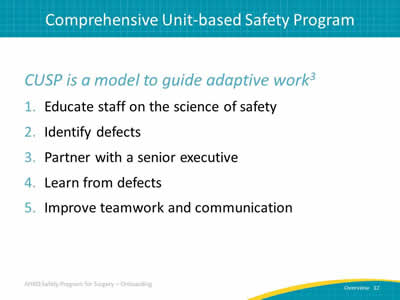

Slide 12: Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program (CUSP)

Say:

To address the adaptive work, we will be using CUSP. CUSP builds on the principles of high-reliability organizations and provides a practical strategy to build capacity at the front line, engage and motivate frontline staff, and give them the voice they need to feel valued and the skills and tools they need to improve care.

CUSP is a five-step process:

- Educate ALL staff on the science of patient safety to help them develop a big-picture perspective, referred to as systems lenses in the Science of Safety program.

- Identify defects by asking staff how the next patient will be harmed and what they think can be done prevent harm.

- Partner with a senior executive within your organization. The senior leader should meet with the safety team at least monthly to help the team better prioritize improvement efforts, align them with current organizational priorities, and create accountability for staff and leadership.

- Learn from defects through collective sensemaking, such as by using structured tools to learn from one defect per quarter.

- Implement teamwork tools and communication

The predominant teamwork tool will be briefings and debriefings based on the successful experience of the World Health Organization, or WHO, and teams will be encouraged to adapt the tool for local use. We will discuss implementation of briefing/debriefing and tapping into the vast experience of teams to learn together as we move forward.

This is an iterative process that, over time, can be a powerful way of improving patient safety culture.

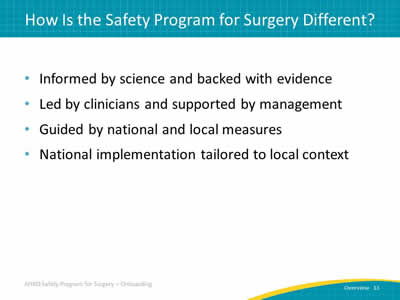

Slide 13: How is Safety Program for Surgery Different?

Ask:

How will this program be different from other initiatives?

Say:

This safety program for surgery is informed by the sciences, and not just the medical sciences (addressing the technical work needed), but also the social sciences. This ensures we address the local values, attitudes, and beliefs that drive our actions.

The program is led by clinicians and supported by management. Far too often, staff feel that quality improvement is something done TO them rather than something done WITH them.

This surgical safety program is guided by measures that clinicians believe are valid.

It provides an improvement framework that can be adapted to meet a hospital “where they are.” It recognizes that many organizations have worked for years to improve surgical care, and helps organizations identify their own defects that are likely leading to surgical complications, including SSI.

Slide 14: Building on Previous State-Level Success...

Say:

The safety program for surgery builds on the lessons learned from previous successful statewide efforts to improve culture and reduce healthcare-associated infections, or HAIs, including the Michigan Keystone ICU program. The Michigan Keystone intensive-care unit, or ICU, program was a multifaceted quality-improvement program that included a checklist to help ensure that providers complied with evidence-based recommendations for the prevention of two other common health care-associated infections, CLABSIs and VAP.

The results were quite impressive. They achieved a 66 percent reduction in CLABSIs and a 71 percent reduction in VAP in over 100 Michigan intensive care units.

Slide 15: ... And National-Level Highlights

Say:

It also builds on the lessons learned from National On the CUSP: Stop BSI program. That program included more than 1,000 ICUs across 44 States and was associated with a 43 percent reduction in CLABSI rates. While many organizations had been working on reducing CLABSI for years, the number of participating ICUs that achieved zero CLABSI rates for a quarter more than doubled during the program.

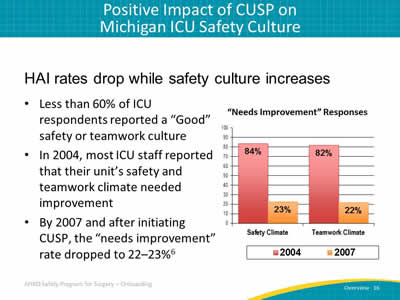

Slide 16: Positive Impact of CUSP on Michigan ICU Safety Culture

Say:

To address the adaptive work, CUSP was used. CUSP is perhaps the best-validated approach to improve teamwork and safety culture on a large scale. In Michigan, CUSP implementation was associated with a dramatic reduction in the number of units that were in the “needs improvement zone” for both teamwork and safety culture.

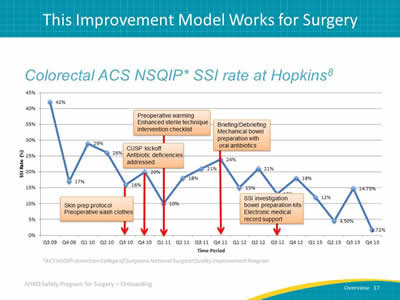

Slide 17: This Improvement Model Works for Surgery

Say:

Evidence shows this approach works. Johns Hopkins, for example, has been using this approach with the support of anesthesia, nursing, and surgical leadership. Hopkins asked staff how the next patient will be harmed and what the hospital can do about it. Combined with emerging evidence and local opportunities identified through auditing performance, Hopkins achieved a 33 percent reduction in colorectal SSI rates.

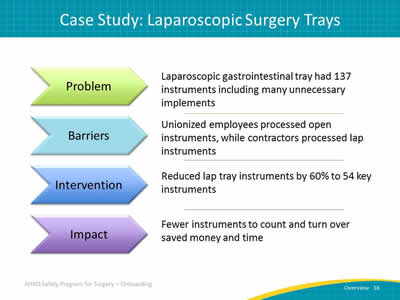

Slide 18: Case Study: Laparoscopic Gastrointestinal Surgery Trays

Say:

We also know this effort of reaching out and tapping into the frontline staff can have additional value. As part of the CUSP program, one of the steps is asking your frontline staff what they think can be done to improve care.

In today’s environment, that is exceedingly important. Hopkins frontline staff pointed out several things that increased value and efficiencies, some not directly related to surgical site infections.

For example, staff appropriately pointed out that every single colorectal or laparoscopic GI team had to open and process a tray that includes more than 137 instruments, many which were never used. We had a chance to reduce costs and improve value. By partnering with our senior leadership through this CUSP teamwork process, we were able to create a new tray with 60 percent fewer instruments and undoubtedly, reduce costs and save time.

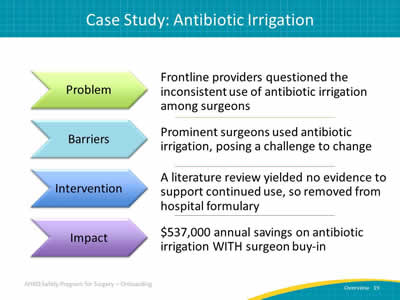

Slide 19: Case Study: Antibiotic Irrigation

Say:

Yet another powerful example of the benefits of tapping into the wisdom of the frontline staff beyond just SSI prevention.

In the second CUSP step, Hopkins asked its teams what could be done to improve care. Teams responded by asking why some surgeons use an antibiotic irrigation within the abdomen and some surgeons don’t. An extensive review of the literature found that no evidence supported the use of that irrigation. Through the partnership with senior leadership, the CUSP team was able to remove antibiotic irrigation products from the formulary, recognizing an impact of over $500,000 in annual savings.

Most remarkably, Hopkins achieved this change by working WITH the surgeon team and gaining its buy-in on the current lack of supporting evidence for antibiotic irrigation. CUSP incorporates the exceedingly important adaptive measures that both allow staff to share observations and provide a forum for open discussion. Before the irrigation products were removed from the formulary, the surgeons were able to weigh in with their views and experiences and respond to the literature. By involving them in the CUSP process and the decision to discontinue the use of these products, even the surgeons previously using the irrigation products accepted and even embraced the discontinuation.

That is the power of CUSP. Of course, the half a million dollars saved each year doesn’t hurt either.

Slide 20: References

Slide 21: References

Slide 22: Building Your Surgical Safety Program Team

Say:

This module focuses on how to work together as a team. The early decisions about how this team is formed will have large impacts on how successful your team ultimately is. We hear a lot about the importance of teamwork and patient safety from the perspective of teams involved in direct patient care, and how you work together on patient safety and quality improvement teams can have similar effects.

Give your team the best possible chance for success by thoughtfully building a strong surgical safety team. This can be one of the most challenging parts of the project, but also one of the most rewarding.

Slide 23: Learning Objectives

Say:

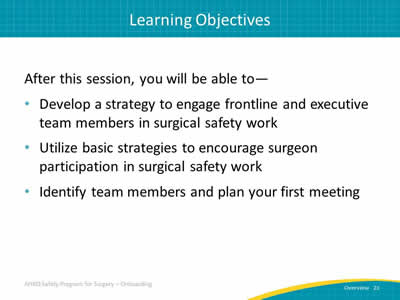

After this session, you will be able to—

- Develop a strategy to engage frontline and executive team members in surgical safety work.

- Utilize basic strategies to encourage surgeon participation in surgical safety work.

- Identify team members and plan your first meeting.

Slide 24: Perioperative Safety Team Members

Say:

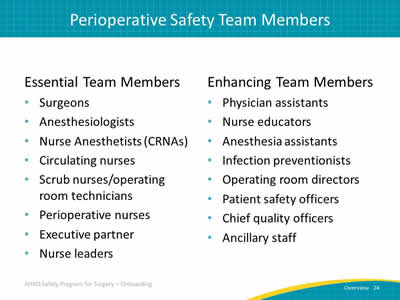

There are no hard and fast rules about specifically who should or should not be on your surgical safety team. Teams will vary based on the specifics of your local needs and organization. However, both the literature and our experience give us several heuristics to think about as you begin to pull your team together, or reflect on how your existing teams are working.

First, let’s talk about “essential” and “enhancing” members of the safety team. The list of essential team members is primarily frontline staff. Anyone whose work is directly impacted by the changes your team will implement needs to have a seat at the table and a voice in the decisions. This is because of the ownership issues described above. Frontline staff need to own patient safety problems. They are the ones who understand how work actually gets done on a day-to-day basis. They are the ones who have a well-tuned sense of where the risks are, of what solutions will work. Ultimately, they are the ones who will have to change their behavior on the job to improve outcomes. These individuals should lead the surgical safety team.

In addition to frontline providers, we include the executive partner as an essential team member. We’ll discuss this role in more detail and why it is so critical later in the module.

Next, the enhancing team members are people with expertise and insight that will be invaluable to the team, but they are not involved in direct patient care. For example, working on SSIs, infection preventionists will have invaluable expertise in the best evidence available and measurement practices. However, their behavior is not what ultimately determines compliance to these strategies. Therefore, they should be in more of a consulting role to the frontline team members leading the effort.

Slide 25: Your Surgical Safety Team

Say:

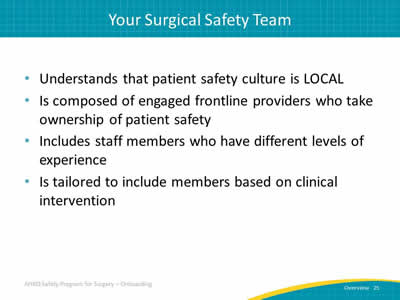

In addition to frontline providers and executive leaders, safety teams should share some other key attributes.

First, the surgical safety team should understand that patient safety and safety culture are LOCAL. The people working together in a given area create the attitudes and expectations of staff that drive perceptions of what behavior is “normal” or accepted each day. Units in the same facility can vary dramatically in culture and in patient outcomes.

Second, that understanding of local culture must be paired with frontline team members who take ownership of patient safety issues. If culture is local, then only people within that culture can change it.

Third, the safety team should Include staff members who have different levels of experience. We already saw that the surgical safety team should be multidisciplinary, but also think about including people at different points in their career path. We tend to pick the same people for similar project teams. However, including less experienced staff members can bring new perspectives, new ideas, and new energy to the work. Successful teams have engaged members, not just experienced members.

Fourth, your safety program team membership should be tailored to include members based on clinical intervention. Think about the “enhancing” team members, and when some of those may take more active roles in the work. You will shift focus over time, and each of these pieces of the technical work may involve different people.

Ask:

Would you reach out to different people if you were working on preoperative warming versus antibiotic redosing?

Slide 26: Surgical Safety Team Logistics

Say:

Fifth, your team should meet regularly. You need consistent meetings to maintain focus and momentum. We recommend weekly meetings, particularly when you are getting started, but monthly meetings are a minimum.

Sixth, your team needs adequate resources including protected time. The executive partner can help obtain these resources. The scarcest resource and the biggest challenge is typically staff time. Your team leader, surgeon, anesthesia, nurse, and infection preventionist specialist will need 2 to 4 hours per week of protected time to engage in project work.

Slide 27: Surgical Safety Teams’ Group Processes

Say:

The effective group processes of safety teams include—

- Role clarity.

- Effective team communication.

- Conflict resolution.

- Education and engagement.

- Senior leadership buy-in, and support.

- Norms.

Successful unit teams have reliable processes in place for team members to work and communicate efficiently. Effective group processes provide opportunities for unit teams to hone their skills in the areas of leadership, role clarity, development of shared interests, collaboration, and feedback.

Effective group work requires that all members share responsibility for group decisions and group interaction while working together on the surgical safety initiative.

Slide 28: Role of Senior Executive Partner

Say:

Active involvement from senior leaders is a known success factor in safety and quality improvement. Relationships with senior leaders can be challenging to build and manage, but effectively engaging executives in this work pays dividends.

These leaders serve several critical functions. First, they can help teams to prioritize their efforts by aligning safety team objectives with other initiatives or priorities in the organization.

Second, executives are well positioned to help the team navigate administrative processes and bureaucracy. Many of the challenges uncovered in safety work may involve organizational policies, purchasing decisions, or interdependencies with other units or departments. Without assistance from someone with expertise and connections in these areas, these challenges may not be under the influence of frontline providers.

Third, the executive partner ensures that the team has the resources it needs to fix the problems it identifies. Typically, an organization’s most valuable resource is the time of its staff, so executives play a large part in setting priorities and ensuring people have time to participate in this work.

Fourth, effective executives have a hands-on leadership style. They come out of their offices to meet with staff in the clinical area on a regular basis. This helps connect people across all levels of the organization and reinforces the value of your surgical safety work.

Slide 29: Finding a Senior Executive Partner

Ask:

So, how do you start to build this relationship with your executive partner?

Say:

Start by contacting the hospital administration for suggestions about who may be a good fit for the project. Remember, the executive does not have to have relevant clinical expertise. His or her role is to provide administrative guidance and support. The frontline providers on the team can solve their own work process issues.

A good candidate for an executive partner meets the following criteria:

- Director level or above.

- Available to attend rounds for at least 1 hour per month.

- Approachable about and comfortable with sensitive topics.

Ideally, you don’t want an executive partner who will dominate the conversation, but someone who will guide and support the team.

Other modules will cover more specifics about how to engage your executive partner. Initially, you will schedule a meeting to introduce the executive to the project, provide a tour of the perioperative area, and share your unit-level data.

Slide 30: Role of Surgeon Leader

Say:

The surgeon leader is charged with advancing the initiative, bridging communication gaps, and securing the buy-in of other surgeons to participate in the safety program initiative.

Surgeon leaders—

- Serve as role models for surgical safety activities.

- Meet with the safety team at least monthly.

- Participate in monthly senior executive partnership meetings.

- Communicate with surgeon groups as needed.

- Help carry out initiatives.

The surgeon leader typically advocates for and supports the initiative, providing the perspective of unit physicians. He or she assists the safety team by educating and communicating with surgeon peers to further the aims of the initiative and ensure the unit surgeons are involved with the program.

The surgeon leader is the surgeon equivalent of the nurse opinion leader or nurse manager on the safety team. The surgeon leader also serves as the communication link between unit physicians and the team. Surgeons on the unit have access to the surgeon leader to voice their concerns and needs. The surgeon leader attends meetings with the safety team at least monthly to help advance the initiative and take an active role in the unit team’s efforts. In addition to these meetings, the surgeon leader also joins monthly senior executive partnership meetings.

The surgeon leader plays a critical role in ensuring the hospital physicians are on the same page as the project lead. The surgeon leader functions as the leader for unit and hospital physicians while contributing to the initiative. Surgeons not serving on the surgical safety team can look to the surgeon leader for guidance and support when implementing the intervention. Having a respected surgeon leader on the team is imperative for addressing resistance to interventions.

Ask:

Can you identify a potential surgeon leader at your hospital who has these characteristics?

Would he or she be a good candidate to participate in a safety team?

Slide 31: Engage Surgeons on the Surgical Safety Team

Say:

When developing a surgical safety team, it is crucial to engage surgeons to work closely with members of the unit team. The surgeon champion recruited for this initiative must be capable of communicating and collaborating effectively with nurses, senior executives, and other team members participating in the initiative.

When engaging surgeons for the surgical safety team, it is important to—

- Identify surgeon leaders.

- Explain the role.

- Listen to surgeon concerns.

- Develop plans to address concerns.

- Reward surgeon leaders.

- Develop a vehicle for communication.

- Formalize communication plan.

Recruiting surgeons to join the initiative will depend on the safety team leader’s ability to tailor the program to match the surgeon leaders’ interests and experience.

Ask:

How will you engage surgeons to participate in the surgical safety team?

Slide 32: Practical Tips for Scheduling Meetings

Say:

We know that some of the seemingly simple barriers can also be the most challenging. Just finding the time to meet can be difficult. But aligning the safety team’s efforts with existing meetings or educational activities can reduce some of the burden. For example, you can integrate safety meetings with regularly scheduled nurse training, unit meetings, grand rounds for physicians, or create joint grand rounds.

Create incentives for participating in the safety team. This can involve a broad range of creative ideas, from trying team improvement goals to financial incentives, to providing social networking incentives such as opportunities for people to present the team’s work to internal and external audiences. Additionally, participation in safety improvement work can be used for continuing education requirements.

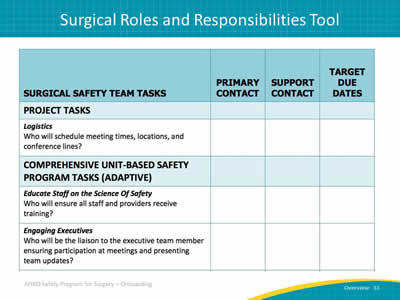

Slide 33: Surgical Team Roles and Responsibilities

Say:

The team roles and responsibilities tool ensures clarity about roles within the team. As with all of our tools, it is designed for editing. Please customize it to meet your needs. List the major project tasks and, as a group, identify a point person, a supporting team member, and target due dates for milestones.

The tool includes three categories: project tasks, adaptive CUSP tasks, and surgical technical tasks. It can help you organize the project tasks and make sure the work is distributed evenly. It is a communication tool that clarifies expectations and holds everyone accountable for their piece of the puzzle.

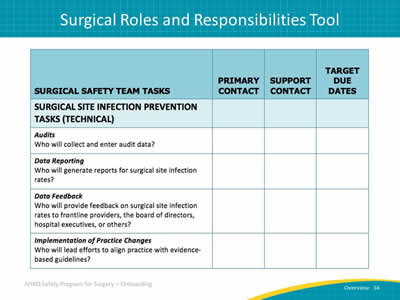

Slide 34: Surgical Team Roles and Responsibilities

Say:

Here are a few of the technical tasks on the Surgical Team Roles and Responsibilities tool.

Slide 35: Next Steps

Say:

Action items for your team are listed here.

Recruit your team. Include a team lead, a nurse lead, a surgeon lead, and an executive partner along with other team members.

Record the names, roles, and contact information. Distribute to team members and post in a central location.

Be proactive in scheduling team meetings for the year. Calendars can fill up quickly and often months in advance, particularly for executives and surgeons.

Complete the Surgical Safety Team Tasks Roles and Responsibilities tool.

Slide 36: Introduction to Building and Measuring Safety Culture

Say:

In this module, you’ll learn about building and measuring patient safety culture. More specifically, you’ll consider the importance of safety culture for your improvement efforts, learn how to measure patient safety culture, and start thinking about how your team may use results from your safety culture assessment to meaningfully inform your efforts to improve care.

Slide 37: Learning Objectives

Say:

Our goals in this module are to define safety culture from a behavioral standpoint and describe what that means for your change and improvement efforts related to this project. We’ll talk about why a strong safety culture is important for facilitating the work of your teams. We’ll consider best practices for measuring patient safety culture and then talk about how these practices are specifically related to the work you’ll do on this project.

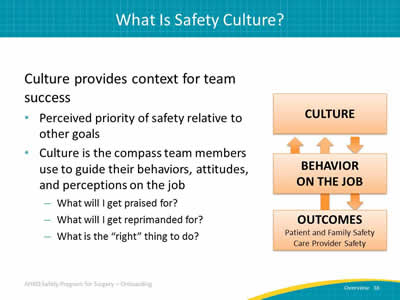

Slide 38: What is Safety Culture?

Say:

What does patient safety culture mean from an operational standpoint? The literature defines safety culture as the perceived priority of safety relative to other goals. Safety culture is the compass that team members use to guide their behaviors, their attitudes, and their perceptions on the job.

Safety culture underpins notions of why certain things are done a certain way in clinical work areas. It sends signals to frontline staff about what they may get praised for and what they might get reprimanded for, and what is the “right” thing to do. Notice that “right” is in quotation marks, because a just or “right” culture sends the signal that safety is the number one priority.

These signals can be in the form of—

- Recognition for taking action in the protected time for patient safety improvement.

- Reinforcement and supports for taking action to protect patients.

Alternatively, in cultures where the “right” thing to do is to get people in and out of beds as fast as possible, patient safety efforts are likely to get less support.

We know culture provides the context for team success because it helps drive behavior on the job. This behavior on the job in turn drives our outcomes, things like patient safety as well as care provider safety and satisfaction.

The other important part to keep in mind as you look at the graphic on the right side of this slide is that culture is continuously evolving. Even though sometimes it seems like it takes a lot to change culture, your behavior and the behavior of your teams on the floor every day are helping to create culture.

Slide 39: Core Aspects of a Safety Culture

Say:

The work of Edgar Schein, a leading organizational and business scientist, helps us understand that patient safety culture is a broad umbrella term comprising many components including the following.

Communication patterns and language

This includes how people talk about issues like hazards or defects.

Ask:

Are these framed as a positive learning experience or something to be ashamed of?

Say:

Feedback, reward and corrective action practices, both formal and informal

This aspect of culture relates to where and how safe practice or speaking up in the name of safety is (or is not) recognized.

Ask:

How is personal responsibility for patient safety communicated and reinforced for all members of your work area?

Formal and informal leader actions and expectations

Do leaders really put safety as their number one priority?

Say:

Leaders who actively demonstrate that a culture of safety is the most critical goal of their work can drive meaningful change.

Teamwork processes are also a critically important component of culture

These include things like backup behavior.

Ask:

Do people offer help if they see that somebody needs it?

Do the members of your work area or unit feel comfortable asking for help if they feel like they need support or an extra pair of hands?

Say:

Leaders can have a significant impact on safety culture when they model and reinforce good teamwork processes.

Resource allocation practices

We know this is always one of the biggest hurdles in patient safety and quality improvement initiatives. We tend to give lip service to patient safety and culture changes, but we do not always provide the resources to back that up. Resources can be in the form of protected time, as well as human and material resources. Adequate resources make a critical difference.

Error detection and correction systems

Ask:

What happens when people put in an error report?

What happens when they informally bring up a concern to another member of their team or to their work area leadership?

Say:

Given that all of these elements combine to define patient safety culture, when we talk about this notion of “good culture” versus “not good culture,” sweeping labels are a misnomer. It’s uncommon for us to see work areas where all of these aspects of culture are poor or all are strong. More typically, you’ll find pockets of excellence and other areas of culture that need work. It’s important as you’re thinking about patient safety culture to identify the strengths and opportunities. Leverage those strengths to facilitate the improvement process.

Slide 40: Why Safety Culture Matters

Ask:

Why does culture matter?

Say:

Patient safety culture influences:

- Patient outcomes, including patient care experience.

- Infection rates and sepsis rates.

- Post-op hemorrhage.

- Respiratory failure.

- Accidental puncture and laceration, as well as general treatment or diagnostic errors.

Importantly, we also know that culture is related to clinician outcomes such as incident reporting and to clinician burnout and turnover.

Slide 41: Why Safety Culture Matters

Say:

Patient safety culture also influences the effectiveness of other safety and quality interventions.

However, if strengthening patient safety culture seems daunting, know that culture CAN meaningfully change through intervention. Some of the best evidence so far is for interventions that use multiple components, recognizing the multiple elements of patient safety culture we spoke of earlier.

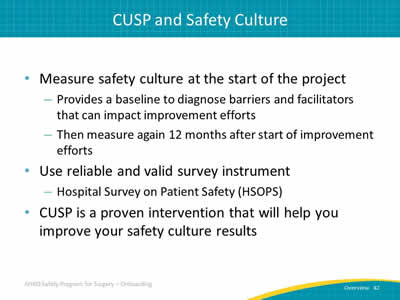

Slide 42: CUSP and Safety Culture

Say:

As part of this work, safety culture is typically measured pre-CUSP. The rationale for this practice is to provide a baseline to diagnose both barriers and facilitators that may impact your improvement efforts. This baseline provides a point of comparison 12 or 18 months after the start of your improvement efforts.

It’s critical when measuring culture to use a reliable and valid survey instrument and to survey ALL members who do the majority of their work in the units or work areas participating in this project. That includes physicians, nurses, technicians, support staff, and others who spend the majority of their time in the participating work area.

For this project we are using the Hospital Survey on Patient Safety (HSOPS) that was developed by AHRQ. Several other surveys have been used to assess safety culture or safety climate. Though our examples will focus on HSOPS, the tools and strategies can be used with any survey instrument that your organization may use to assess safety culture. No matter what method you select, the critical point is that your efforts don’t stop at data collection.

Your teams will be using CUSP as an intervention to help improve your culture results.

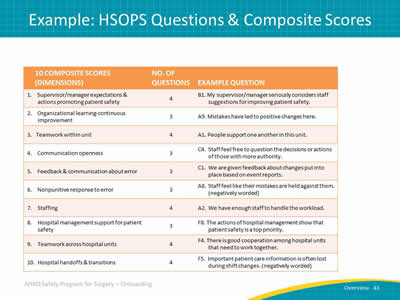

Slide 43: Example: HSOPS Questions & Composite Scores

Say:

We will take just a few minutes to review the details of the survey. If your organization uses a different survey is assess patient safety culture, it is important to understand similar details about it.

The HSOPS measures 10 composite scores, or dimensions, of safety culture. These dimensions provide insight into things like—

- Supervisor and manager expectations and actions regarding patient safety.

- Actions promoting safety.

- Organizational learning and commitment to continue with improvement.

- Teamwork.

- Communication and more.

A composite score really is just a roll-up score, an aggregate of several different questions. Composite scores provide your big-picture overview. You can then dive deeper and look at responses to specific questions in a targeted area that make up the composite scores.

Note: The example questions are listed with the alphanumeric order from the HSOPS.

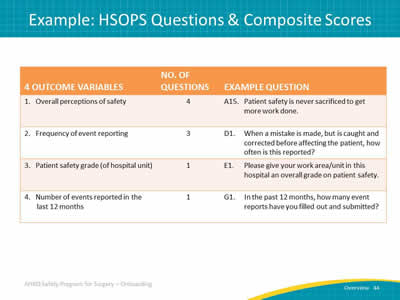

Slide 44: Example: HSOPS Questions & Composite Scores

Say:

The HSOPS also includes four outcome variables. These are self-reported outcomes that reflect an overall measure of clinician and staff perceptions of safety. There’s also an outcome question asking about the frequency of event reporting. They ask for an overall patient safety grade and then also ask your clinicians and staff to comment on the number of events reported in the last 12 months.

The survey also includes several background questions. It asks how long clinicians and staff have worked in their unit and how long they’ve worked in their particular hospital. Seniority in a particular unit or in a particular hospital can impact safety culture scores as well.

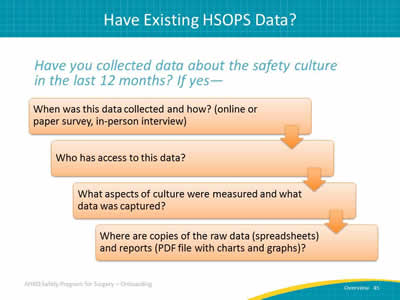

Slide 45: Have Existing HSOPS Data?

Say:

Regardless of which survey you use to collect information about the culture of safety in your work area, it is important to ask several questions as part of your CUSP work.

These include—

- Have data about the safety culture in our work area been collected in the last 12 months?

- If not, can we, as part of our CUSP teamwork, administer a survey to collect information about safety culture in the work areas participating in this project?

- If so, who has access to the results/data from this effort to measure safety culture?

- If, so what data collection method was used?

- Survey?

- Interviews?

- Focus groups?

- Alternative method?

- When was this information collected and how (e.g., online survey, paper survey, in person interviews)?

- What aspects of culture were measurement/what data were captured?

Ask:

Is it possible to obtain copies of the raw data (e.g., an excel file of responses) or only reports (e.g., PDF file with charts and graphs)?

Slide 46: References

Slide 47: References

Slide 48: References

Slide 49: Next Steps

Slide 50: Preparing to Lead

Ask:

What percentage of organizational change efforts fail?

Say:

More than 70 percent fail.

But there is something redeeming about that figure. When change efforts fail, they often do for predictable reasons.

A postmortem or a debriefing after a loss is important, but you have to endure the loss or death. In a postmortem, an autopsy is performed to learn why a patient died. While it may be helpful to those interested in the results, it does not help the central figure in the medical drama–the patient.

You can identify reasons for failure with a premortem exercise. A premortem helps prevent losses from occurring. So, it’s used to identify potential barriers and vulnerabilities before they occur.

Slide 51: Premortem Exercise

Say:

There are four steps. Take these steps back to your team and complete the premortem exercise during your first surgical safety meeting.

First, imagine that it is 2 years into the future, and despite all of your efforts, the project has failed catastrophically.

ASK?

What happened?

Say:

Maybe no one in your team is engaged. Maybe no one even ever heard of Safety Program for Surgery and patient care hasn’t improved.

Ask:

What does your worst-case scenario look like?

Slide 52: Premortem Exercise

Say:

In step two, you want to think about what could have caused your project to fail. So, take a couple minutes and brainstorm all of the reasons that the failure occurred.

Ask:

Was your staff overburdened or were there too many competing priorities?

What happened?

What could have caused your project to fail?

Slide 53: Premortem Exercise

Say:

In step three, think about what actions you can take to prevent that failure from occurring. Prioritize the list generated in step two and identify ways that you can address the top two or three items. Also decide which contributing elements are most likely to occur and/or which are the easiest to fix. Basically, identify the low-hanging fruit. Then create a concrete plan to address those issues as well.

Ask:

What specific actions can you take to avoid or manage these concerns?

Slide 54: Premortem Exercise

Say:

Step four involves revisiting the premortem. Review the list of things that might have caused your project to fail, and as the project continues, sensitize yourself to the things that you anticipated. Also, add any emerging obstacles.

I think as clinicians we learn to anticipate problems. That’s the same frame of mind to maintain through this project. Anticipate the reasons for failure and try to mitigate them before they can derail project success.

Slide 55: Premortem Summary

Say:

Below is a summary of the different steps of the premortem.

- Two years out, what does the worst-case scenario look like?

- What could have caused your project to fail?

- What specific actions can you take to avoid or manage these issues?

- Review and anticipate potential problems throughout the project.

Complete this premortem exercise with your surgical safety team.