Placement, Maintenance, and Removal

Before any procedure, the individual inserting the device needs to evaluate the indication and the potential risk associated with the device use. The device (PVC, CVC, UC, ventilator) placement should follow proper insertion technique. All devices are removed as soon as they are no longer needed or when a complication is identified (if at all possible). Evaluating the device daily for necessity will reduce unnecessary use, thus reducing the infection risk. Figure 1 illustrates the three areas of focus in reducing invasive device risk.

Figure 1. The three areas of focus to reduce device risk: placement, maintenance, and removal

Peripheral Venous Catheters

Before a PVC is inserted, an evaluation of necessity (indication) should be done. That is, does the care require intravenous access? Then, proper insertion includes the health care worker (1) performing hand hygiene before contact with patient, (2) cleansing the area where the PVC will be placed for 30 seconds with antiseptic (chlorhexidine-alcohol), (3) allowing 30 seconds for the antiseptic to dry (without fanning or blowing), (4) not contaminating the cleansed area during procedure, and (5) applying a sterile dressing securely. Complying with the five steps during the procedure will reduce the risk of introducing organisms to the PVC site, thus reducing the risk for infection. Proper maintenance of the PVC includes hand hygiene and scrubbing the hub with alcohol for 15 seconds before accessing the PVC or infusion of medications. Another important component of PVC maintenance is ensuring that the site does not show signs of infection or mechanical problems (phlebitis or infiltration). The PVC dressing should be intact at all times. Minimizing the risk of infectious and noninfectious complications hinges on the daily evaluation for continued need and assessment for any local signs of mechanical or infectious complications. While RPs do not routinely place PVCs, they are greatly involved in the direct daily care of patients and therefore should pay close attention to PVC sites and any related patient complaints. All PVCs placed under aseptic conditions should be changed after 96 hours of use (or per hospital policies), or if signs of mechanical or infectious problems occur. PVCs emergently placed (placed under suboptimal conditions where asepsis was not maintained during insertion) should be documented and labeled to reflect their state, then removed within 24 hours of placement. Finally, if the catheter is not needed, it should be removed.

Team members involved: Nurse, resident physician, intravenous therapy team, and attending physician.

Central Venous Catheters

Before a CVC is placed, an evaluation of necessity (indication) should be done. That is, does the care require central venous access? Indications include (1) no feasible peripheral venous access, (2) the use of pressors and hemodynamic monitoring, and (3) the use of medications that are phlebitogenic or require central access for infusion. More recently, PICCs have become popular in the hospital setting and are used in patients who may require intravenous access for more than a week (e.g., intravenous antibiotics or total parenteral nutrition). Many CVCs are used for longer than needed, often for convenience. A CVC should be inserted under full barrier precautions and aseptically. Components of the insertion procedure include practicing hand hygiene, wearing a cap, mask, gown, and sterile gloves, and creating a sterile field using a large drape. The antiseptic used should be chlorhexidine-alcohol (superior to betadine for antisepsis). A chlorhexidine disc or gel may also be applied at the CVC exit site to reduce colonization risk in hospitals with persistently elevated observed CLABSI events. Using ultrasound guidance for internal jugular CVC insertion is associated with lower mechanical complications. Emergently placed CVCs (those not placed under aseptic conditions) should be labeled with plans to remove within 24 hours. Maintenance of the CVC includes at least daily evaluation by the RP for any local signs of infectious or noninfectious complications. Whenever the CVC is accessed, the site should be evaluated (for example, nursing should regularly evaluate the site when infusing medications). When accessing the CVC, scrubbing the hub with alcohol for 15 seconds is recommended to reduce the risk of intraluminal contamination. Another important maintenance element is ensuring the dressing is intact. The risk of CVC infection increases the longer the catheter is used. Routine catheter change is not recommended, has not been shown to reduce infection risk, and may be associated with mechanical complications. CVCs should be assessed daily (Ask: What is the line being used for?) and removed if no longer needed. In addition, high-risk lines (emergently placed or femoral site [especially in obese patients]) should be removed and lower risk alternatives used. Another opportunity to evaluate the continued need for a CVC is at the time of transfer from the ICU to other hospital units.

Team members involved: Resident physician, nurse, intravenous therapy team, and attending physician.

Urinary Catheters

Before a UC is placed, an evaluation of necessity (indication) should be done (i.e., does the patient need a urinary catheter?). The appropriate indications are based on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee guidelines. Appropriate indications include—

- Acute urinary retention or obstruction. This includes outflow obstruction. Examples include prostatic hypertrophy with obstruction, urethral obstruction related to severe anasarca, and urinary blood clots with obstruction. Acute urinary retention may be medication induced, medical (neurogenic bladder), or related to trauma to the spinal cord.

- Perioperative use in selected surgeries. Urologic surgery or other surgery on contiguous structures of the genitourinary tract are appropriate indications. In addition, anticipated prolonged duration of surgery, large volume infusions during surgery, or need for intraoperative urinary output monitoring are also acceptable. Spinal or epidural anesthesia may lead to urinary retention (prompt discontinuation of this type of anesthesia should prevent the need for urinary catheter placement).

- Assistance with healing of perineal and sacral wounds in incontinent patients. This is an indication when there is concern that urinary incontinence is leading to worsening skin integrity in areas of skin breakdown.

- End-of-life care (hospice/comfort/palliative care). This addresses patient comfort at end of life. Some patients may not want the catheter.

- Required immobilization for trauma or surgery. Examples include an unstable thoracic or lumbar spine, multiple traumatic injuries such as pelvic fractures, and acute hip fracture with risk of displacement with movement.

- Accurate measurement of urinary output in critically ill patients. This applies to patients who are critically ill and are expected to be cared for in the intensive care setting. It is important to clearly identify what is considered to be an indication for fluid monitoring in a critically ill person. A recent update of the indications published by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America clarified the need as “hourly assessment of urine output in patients in an ICU.”

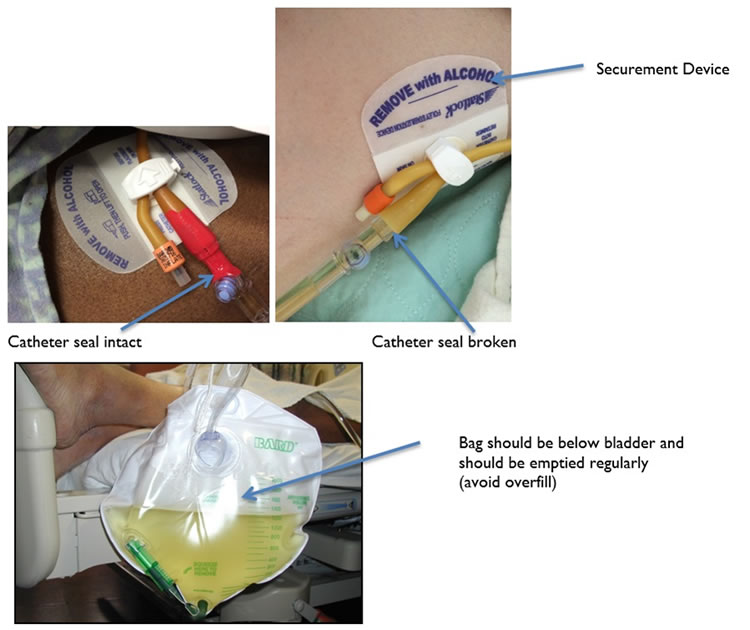

The ED, through which more than half of hospitalized patients are admitted, represents an attractive unit to prevent inappropriate placement of UCs. Before deciding on the insertion of a UC, noninvasive devices (ultrasound, a.k.a. bladder scan) may be used to evaluate for retention or bladder volume. In addition, alternatives to the UC (e.g., condom catheter or frequent toileting) may help avoid inappropriate use. If the patient has an appropriate indication for UC use, an indwelling UC is placed under aseptic conditions. Proper insertion includes (1) performing hand hygiene before and after placement, (2) maintaining aseptic technique and use of sterile equipment, (3) using sterile gloves, drape, an antiseptic solution for periurethral cleaning, and a single packet of lubricant for insertion, (4) using the appropriate catheter size, and (5) having all the elements needed for procedure in one kit. Maintenance includes keeping a closed urinary drainage system, an unobstructed urinary flow (no kinks, urinary bag placement below bladder, and regular emptying of the urinary bag), a securement device (to reduce catheter movement and trauma risk), and an unbroken catheter seal. Figure 2 illustrates the recommendations above.

Figure 2. Urinary catheter maintenance elements to reduce complication risk

The indwelling UC may be associated with many infectious and noninfectious complications including immobility (with potential pressure ulcers and increased risk for thromboembolism), trauma, and debility. The best risk reduction strategy is to evaluate the continued need for the UC daily and promptly remove the device when no longer indicated. ICUs have about three to four times as high utilization of UCs compared with non-ICUs. Patient transfers from the ICU to a non-ICU represent an important opportunity to evaluate and remove UCs.

Team members involved: Resident physician, nurse, certified nurse’s assistant or technician, and attending physician.

Ventilators

Mechanical ventilation is indicated when the patient’s clinical and laboratory assessments indicate the inability to sustain adequate oxygenation or ventilation. The decision to intubate and mechanically ventilate the patient is made if noninvasive positive pressure ventilation is not an option or has failed. Common indications include respiratory failure, cardiac or pulmonary arrest, laryngeal trauma or edema, and deep coma with the risk of aspiration. For intubated patients, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America recommendations for VAP reduction (maintenance) include (1) minimizing sedation through sedation interruption daily with spontaneous awakening trials, daily assessment of readiness for extubation, and pairing breathing and awakening trials, (2) improving physical conditioning with early mobility, (3) reducing pooling of secretions above the endotracheal tube cuff using subglottic secretion drainage in high-risk patients, (4) keeping the head of the bed elevated 30–45 degrees, (5) reducing the risk of contamination and pooling in the ventilator circuit, and (6) performing regular oral care. Finally, the risk of ventilator-associated complications (infectious and noninfectious) is best mitigated by limiting the duration of mechanical ventilation (i.e., extubation [removal] when the patient is able to breathe without support).

Team members involved: Resident physician, attending physician, nurse, and respiratory therapist.