Improving Communication and Teamwork in the Surgical Environment Module

Slide 1: Improving Communication and Teamwork in the Surgical Environment Module

Slide 2:

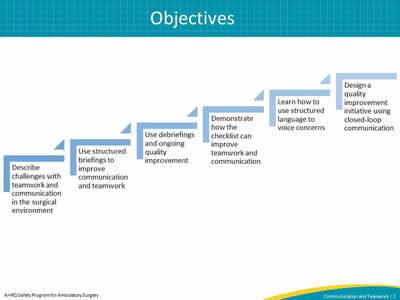

Image: The objectives are listed as a series of ascending steps:

Describe teamwork and communication issues in the surgical environment,

Apply structured briefings to improve communication and teamwork,

Utilize team debriefings to improve communication and systemize ongoing quality improvement efforts,

Demonstrate how teamwork and communication can be improved using the checklist,

Learn how to use structured language to address concerns, and;

Design a quality improvement initiative that targets closed loop communication among team members.

Slide 3: Overview

- Communication and teamwork defined.

- Improving surgical team communication with briefings.

- Improving surgical team communication with debriefings.

- The surgical checklist as a communication and teamwork tool.

- Customizing the surgical checklist.

- Speaking up using structured language.

- Closed-loop communication.

Slide 4: Communication and Teamwork Defined

This section covers—

- The definition of communication.

- Barriers to effective communication.

- The impact of poor communication on patient outcomes.

- The definition of teamwork.

- The impact of poor teamwork on patient outcomes.

- Perceptions of teamwork among members.

Slide 5: Communication Is—

- Getting the necessary information to the right people so decisions can be made.

- The interaction among members of the surgical team.

- Briefing

- Debriefing

Slide 6: The Problem: Challenges of Effective Communication

- Operating and procedure rooms are chaotic and noisy environments.

- Visual and auditory cues are hard to see and hear when people are wearing masks.

- The person who is supposed to act on information isn't always clearly identified.

Image: Clip art showing a brick wall between one provider and another, with lines indicating the wall blocking vision

Slide 7: The Impact of Poor Communication on Patient Outcomes

- Studies show that communication failures are the cause of 80 percent of adverse events1

- Lack of communication has resulted in—

- Wrong sites

- Wrong procedures

- Incorrect implants

- Missing equipment

- Mislabeling of specimens

- Delays in surgery

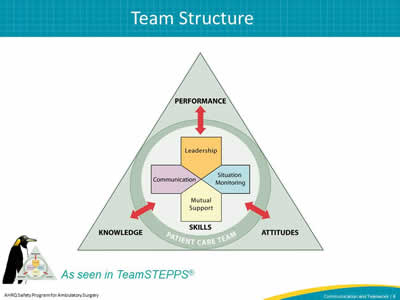

Slide 8: Team Structure

Image: The Team Structure slide includes the TeamSTEPS triangle logo which explains how Performance, Attitudes, and Knowledge all affect the patient care team.

Slide 9: High-Performing Teams

Teams that perform well2—

- Hold shared mental models.

- Have clear roles and responsibilities.

- Have clear, valued, and shared vision.

- Optimize resources.

- Have strong team leadership.

- Engage in a regular discipline of feedback.

- Develop a strong sense of collective trust and confidence.

- Create mechanisms to cooperate and coordinate.

- Manage and optimize performance outcomes.

Slide 10: The Impact of Poor Teamwork on Patient Outcomes

Patients whose surgical teams exhibited fewer teamwork behaviors were at higher risk for death or complications.3

Image: Clip art of a nurse and physician collaborating beside their patient and the patient's family member.

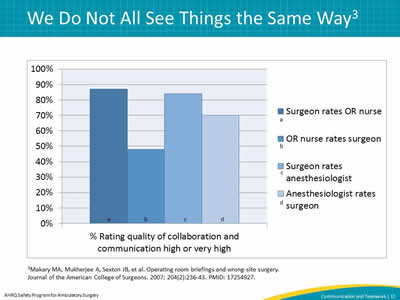

Slide 11: We Do Not All See Things the Same Way3

Image: % Rating quality of collaboration and communication high or very high vary based on role and job title. While surgeons often rate OR nurses higher, the inverse is not true. There are also differences between anethesiologists and their perception of surgeon's communication.

3Makary MA, Mukherjee A, Sexton JB, et al. Operating room briefings and wrong-site surgery. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2007; 204(2):236-43. PMID: 17254927.

Slide 12: Improving Surgical Team Communication With Briefings

This section covers—

- Briefing defined.

- The story of briefings in the surgical environment.

- Benefits of team briefings.

- Components of a good briefing.

- Example of a briefing in an ambulatory surgery center.

Slide 13: A Briefing Is a Discussion That—

- Facilitates clear and effective communication.

- Gets the team on the same page.

- Creates a sense of teamwork and collaboration.

- Fosters an environment where team members can openly address a perceived problem.

- Every member of the team actively participates in .

- Can set the tone for the day and/or procedure.

Slide 14: Historical Perspective: The Orange County Briefing Card at Kaiser Permanente4

- Kaiser Permanente created preprocedural briefing cards for its Orange County hospitals in 2003.

- Contained key information for the entire team.

- Cards were placed in every operating room.

- Reduced wrong-site surgeries and other adverse events.

- Increased staff morale.

- Reduced nursing turnover.

Image: Clip art of a clipboard with a checklist on it.

4Shepard S. Teamwork in the OR. The Doctors Company: Patient Safety/Risk Management Strategies. An Ounce of Prevention. 2015. Accessed May 2015.

Slide 15: Briefings Help Us To—

- Better "know the game plan" and "be on the same page".

- Monitor a situation and raise red flags.

- Ensure each other's needs and expectations are met.

- Avoid unwanted surprises.

- Reduce surgical flow disruptions.

- Improve patient safety.

Slide 16: Components of a Good Briefing

- All team members introduce themselves.

- Team confirms—

- Patient identification.

- Procedure/surgical site and side.

- Surgeon shares operative plan and possible difficulties.

- Anesthesia professional shares anesthetic plan and airway and/or other concerns.

- Nurse and scrub tech share equipment issues and/or other concerns.

- Nurse and scrub tech confirm medications are correct and labeled and implant is the correct type and size.

- Surgeon sets the tone with a statement

- "Does anybody have any concerns? If you see something that concerns you during this case, please speak up."

Slide 17: Briefing

Image: Video icon

Click to play

Select to play video: https://youtu.be/NhFU4h3aQE4

Slide 18: Improving Surgical Team Communication With Debriefings

This section covers—

- The definition of debriefing.

- The benefits of team debriefing at the end of a case.

- Components of a good debriefing.

- Example of a debriefing in an ambulatory surgery center.

- Timing of the debriefing discussion.

- The use of debriefings for continuous quality improvement.

Slide 19: A Debriefing Is a Discussion Where—

- All team members participate before the patient is transferred to recovery.

- Team members reflect on what happened during the procedure.

- This gives the team a chance to discuss—

- Making a plan for the recovery of the patient.

- Equipment problems encountered.

- Improvements that could have made the procedure safer and/or more efficient.

Image: TeamSTEPPS logo” and “As seen in TeamSTEPPS®

Slide 20: Benefits of Debriefing

- Ensures all team members are on the same page.

- Confirms critical information.

- Provides a place to discuss adverse or potentially adverse events that occurred.

- Facilitates discussion of how to stop problems from reoccurring.

- Promotes patient safety.

Slide 21: Components of a Good Surgical Debriefing

- Verification of sponge and needle count.

- Review of the procedure performed.

- Confirmation of specimen labeling.

- Discussion of—

- Equipment issues or problems.

- Key concerns for patient recovery and management.

- Actions needed to make the next case safer or more efficient.

Slide 22: Debriefing

Image: Video icon

Click to play

Select to play video: https://youtu.be/fKmNhVn9R1I

Slide 23: Timing the Debriefing Discussion

- A good practice is to conduct the debriefing discussion in the operating or procedure room.

- The team should decide whether the debriefing should occur with the patient present.

- The debriefing should take place as soon after the procedure as possible.

- It may be helpful to begin the debriefing after the sponge counts have been completed or when the surgeon or physician removes their gloves.

Slide 24: Problems Identified by Debriefings

- Near misses.

- Incorrect sponge and needle counts.

- Equipment issues.

- Mislabeling of specimens.

Slide 25: Using Debriefings for Continuous Quality Improvement

- Create a way to collect identified problems or other important information.

- Designate someone in the facility to monitor and fix problems identified.

- Update those who reported problems about steps taken to fix them.

Slide 26: The Surgical Checklist as a Communication and Teamwork Tool

This section covers—

- Checklist background and evidence.

- The checklist as a vehicle for briefings and debriefings.

- Examples of surgical checklists that incorporate communication and teamwork.

Image: Clip art of clipboard with checklist on it.

Slide 27: The Surgical Checklist

- Integrates process and communication items into one tool.

- Ensures that the team discusses and performs critical safety steps for every patient at all times.

- Requires the surgical team to stop at three critical points for safety review

- Before induction of anesthesia/before the patient enters the operating room.

- Before skin incision/start of the procedure.

- Before the patient leaves the room.

- Designed to be—

- Used by the entire team.

- Read aloud from a hard copy.

Slide 28: Benefits of the Checklist

- Enhances communication among team members.

- Raises awareness of what's happening in the room.

- Sets a positive tone.

- Improves teamwork.

Image: Clip art of patient on operating table with medical staff going over checklist.

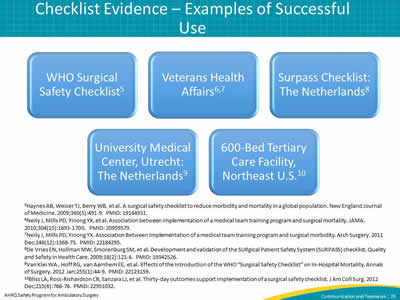

Slide 29: Checklist Evidence – Examples of Successful Use

Image: Five examples of successful checklist use, each listed in a box

Who Surgical Safety Checklist5

Veterans Health Affairs6,7

Surpass Checklist: The Netherlands8

University Medical Center, Utrecht: The Netherlands9

600-Bed Tertiary Care Facility, Northeast US10

Slide 30: Checklists Used as Communication Tools

- WHO Surgical Safety Checklist.

- Safe Surgery 2015 Checklist.

- Cardiac Surgery Checklist.

- Endoscopy Checklist.

- Ambulatory Surgery Center Checklist.

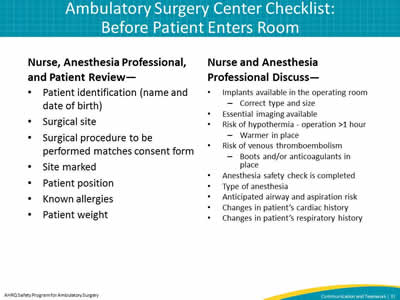

Slide 31: Ambulatory Surgery Center Checklist: Before Patient Enters Room

Nurse, Anesthesia Professional, and Patient Review—

- Patient identification (name and date of birth)

- Surgical site

- Surgical procedure to be performed matches consent form

- Site marked

- Patient position

- Known allergies

- Patient weight

Nurse and Anesthesia Professional Discuss—

- Implants available in the operating room

- Correct type and size

- Essential imaging available

- Risk of hypothermia - operation >1 hour

- Warmer in place

- Risk of venous thromboembolism

- Boots and/or anticoagulants in place

- Anesthesia safety check is completed

- Type of anesthesia

- Anticipated airway and aspiration risk

- Changes in patient's cardiac history

- Changes in patient's respiratory history

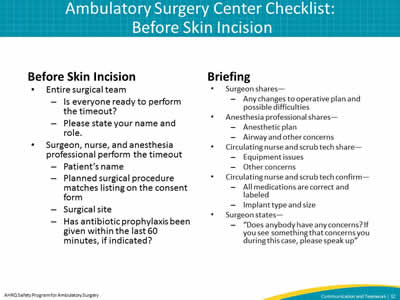

Slide 32: Ambulatory Surgery Center Checklist: Before Skin Incision

Before Skin Incision

- Entire surgical team

- Is everyone ready to perform the timeout?

- Please state your name and role.

- Surgeon, nurse, and anesthesia professional perform the timeout

- Patient's name.

- Planned surgical procedure matches listing on the consent form.

- Surgical site.

- Has antibiotic prophylaxis been given within the last 60 minutes, if indicated?

Briefing

- Surgeon shares—

- Any changes to operative plan and possible difficulties.

- Anesthesia professional shares—

- Anesthetic plan.

- Airway and other concerns.

- Circulating nurse and scrub tech share—

- Equipment issues.

- Other concerns.

- Circulating nurse and scrub tech confirm—

- All medications are correct and labeled.

- Implant type and size.

- Surgeon states—

- "Does anybody have any concerns? If you see something that concerns you during this case, please speak up"

Slide 33: Ambulatory Surgery Center Checklist: Before Patient Leaves the Room

Before Patient Leaves Room

- Nurse reviews with team—

- Instrument, sponge, and needle counts are correct

- Name of the procedure performed

- Specimen labeling

- Read back specimen labeling including patient's name

Debriefing

- Surgical team discusses—

- Equipment problems that need to be addressed.

- Key concerns for patient recovery and management.

- Actions needed to make the next case safer or more efficient.

Slide 34: Customizing the Surgical Checklist

This section covers—

- How to build an implementation team.

- What to think about when customizing your checklist.

- How to test your checklist outside of the patient environment using tabletop simulation.

- How to test your checklist in the patient environment.

Slide 35: Building an Implementation Team

- Create a team that will help lead this work in your facility.

- At a minimum the team should include at least one—

- Administrator

- Surgeon/physician

- Anesthesia professional

- Nurse

- Scrub technician

Image: Clip art of four people and leader, with three people raising their hands and leader pointing to someone to pick that person.

Slide 36: Things To Consider When Customizing Your Checklist

- It should be customized to fit the needs of your facility.

- Think about—

- Cases

- Patient population

- Special needs

- Do not make your checklist too long.

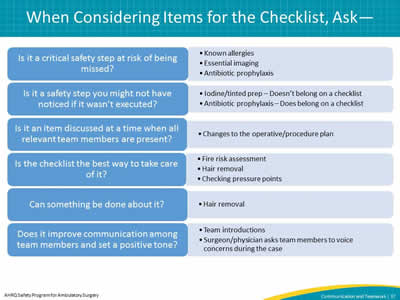

Slide 37: When Considering Items for the Checklist, Ask—

|

Is it a critical safety step at risk of being missed? |

|

|

Is it a safety step you might not have noticed if it wasn't executed? |

|

|

Is it an item discussed at a time when all relevant team members are present? |

|

|

Is the checklist the best way to take care of it? |

|

|

Can something be done about it? |

|

|

Does it improve communication among team members and set a positive tone? |

|

Slide 38: Testing Your Checklist Outside of the Patient Environment Using Tabletop Simulation – Part One

- This is the first place to try your checklist after making changes.

- Testing the checklist outside of the operating room/procedure room helps identify items you may want to change without making mistakes on patients.

- Say the words on the checklist aloud and pretend you are in a real case. Often the words look good on paper but do not necessarily reflect what you would say in an actual case.

Image: Clip art of tabletop simulation

Slide 39: Example of a Tabletop Simulation Part One

Image: Video icon

Click to play

Select to play video: https://youtu.be/V_nU8WxCH2w

Slide 40: Testing Your Checklist Outside of the Patient Environment Using Tabletop Simulation – Part Two

- After reviewing the checklist, discuss the changes needed before using it on a patient.

- Assign team members tasks, and make changes based on feedback if necessary.

Image: Clip art of tabletop simulation.

Slide 41: Example of a Tabletop Simulation Part Two

Image: Video icon

Click to play

Select to play video: https://youtu.be/FY1ZgmC4oJU

Slide 42: Testing Your Checklist in the Patient Environment

- Test the checklist with one team for one case, and modify as necessary.

- Test the checklist with one team for one day, and modify as necessary.

- This process may be repeated multiple times with the same team or with different teams to make sure your checklist works before finalizing it.

Slide 43: Speaking Up Using Structured Language

This section covers—

- The importance of voicing concerns in the surgical environment.

- The barriers to speaking up.

- The solution – the use of structured language.

- The CUS technique.

- Examples of speaking up.

Image: TeamSTEPPS logo

As seen in TeamSTEPPS®

Slide 44: Why Voicing Concerns in the Surgical Environment Is Important

Problems that happen because no one addressed them

- Wrong site

- Wrong procedure

- Wrong/missing implant

- Wrong medications

- Unidentified allergy

- Wrong equipment

Image: Clip art of medical professional raising hand.

Slide 45: Barriers to Speaking Up

- Fear of—

- Being embarrassed

- Feeling stupid

- Being ridiculed

- Being yelled at

- Being wrong

- Saying something that's not important

- Thinking that—

- "They won't listen anyway."

- "It's not that important."

Slide 46: The Solution: Structured Language

- Use special words that indicate there is a problem.

- Both the sender and the receiver need to understand these words.

Image: Clip art of patient on operating table with medical team going over checklist.

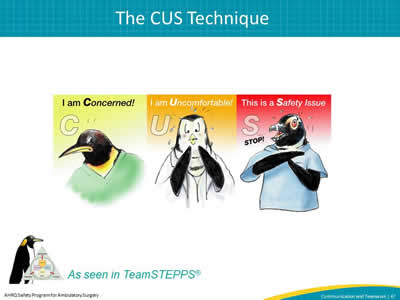

Slide 47: The CUS Technique

Images: "CUS" stands for I am concerned, I am uncomfortable, This is a safety issue and

TeamSTEPPS logo

As seen in TeamSTEPPS®

Slide 48: Examples of Speaking Up

Images: Clip art of medical team and Audio Example of Speaking Up - Transcript of recording is available on the website.

Select audio symbol to play audio, or access audio at: https://www.ahrq.gov/hai/tools/ambulatory-surgery/sections/implementation/training-tools.html.

Slide 49: Closed-Loop Communication

This section covers—

- Closed-loop communication defined.

- How closed-loop communication works.

- Examples of closed-loop communication.

Slide 50: The Solution: Closed-Loop Communication

- Improves the team's ability to exchange clear and concise information.

- Acknowledges receipt of that information.

- Confirms that information is clearly understood.

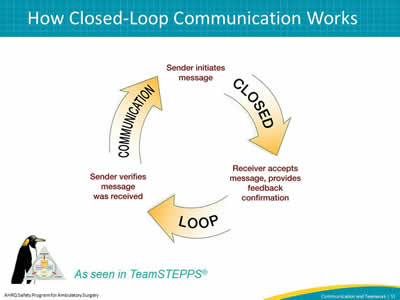

Slide 51: How Closed-Loop Communication Works

Image: Illustration of closed loop communication, with three steps arranged in a circle and arrows pointing to the next step

- The sender initiates message.

- Receiver accepts message, provides feedback confirmation.

- Sender verifies message was received.

Image: TeamSTEPPS logo

As seen in TeamSTEPPS®

Slide 52: Closed-Loop Communication Example

Images: Patient in bed with medical team standing next to bed and

Audio Example of Closed Loop Communication - Transcript of recording is available on the website.

Select audio symbol to play audio, or access audio at: https://www.ahrq.gov/hai/tools/ambulatory-surgery/sections/implementation/training-tools.html

Slide 53: Summary

- There is an opportunity for us to improve patient care by improving teamwork and communication.

- Ways to improve teamwork and communication

- Have the entire team perform a briefing before every case and a debriefing at the end of every case.

- Bring briefing and debriefing into the surgical environment by using the surgical checklist.

- Use structured language.

- Teach people closed-loop communication.

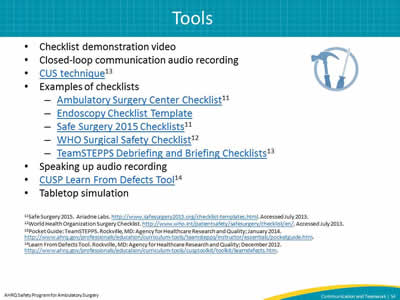

Slide 54: Tools

- Checklist demonstration video.

- Closed-loop communication audio recording.

- CUS technique13

- Examples of checklists

- Speaking up audio recording

- CUSP Learn From Defects Tool14

- Tabletop simulation.

Slide 55: References

- Mazzocco K, Petitti D, Fong KT, et al. Surgical team behaviors and patient outcomes. Am Journ Surg. 2009;197(5):678-85. PMID: 18789425.

- Salas E, Burke CS, Stagl KC. Developing teams and team leaders: Strategies and principles. In: Demaree RG, Zaccaro SJ, Halpin SM, editors. Leader development for transforming organizations. April 2004 as cited in: TeamSTEPPS Fundamentals Course: Module 1. Introduction. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; March 2014.

- Makary MA, Mukherjee A, Sexton JB, et al. Operating room briefings and wrong-site surgery. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2007; 204(2):236-43. PMID: 17254927.

- Shepard S. Teamwork in the OR. The Doctors Company: Patient Safety/Risk Management Strategies. An Ounce of Prevention. 2015. Accessed May 2015.

- Haynes AB, Weiser TJ, Berry WB, et al. A surgical safety checklist to reduce morbidity and mortality in a global population. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;360(5):491-9. PMID: 19144931.

- Neily J, Mills PD, Yinong YX, et al. Association between implementation of a medical team training program and surgical mortality. JAMA. 2010;304(15):1693-1700. PMID: 20959579.

- Neily J, Mills PD, Yinong YX. Association Between Implementation of a medical team training program and surgical morbidity. Arch Surgery. 2011 Dec;146(12):1368-73. PMID: 22184295.

- De Vries EN, Hollman MW, Smorenburg SM, et al. Development and validation of the SURgical Patient Safety System (SURPASS) checklist. Quality and Safety in Health Care. 2009;18(2):121-6. PMID: 19342526.

- Van Klei WA , Hoff RG, van Aarnhem EE, et al. Effects of the Introduction of the WHO “Surgical Safety Checklist” on In-Hospital Mortality. Annals of Surgery. 2012 Jan;255(1):44-9. PMID: 22123159.

- Bliss LA, Ross-Richardson CB, Sanzara LJ, et al. Thirty-day outcomes support implementation of a surgical safety checklist. J Am Coll Surg. 2012 Dec;215(6):766-76. PMID: 22951032.

- Safe Surgery 2015. Ariadne Labs. Accessed July 2013.

- World Health Organization Surgery Checklist. Accessed July 2013.

- Pocket Guide: TeamSTEPPS. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; January 2014.

- Learn From Defects Tool. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; December 2012.