Improving Communication and Teamwork in the Surgical Environment Module: Facilitator Notes

Slide 1: Improving Communication and Teamwork in the Surgical Environment Module

Say:

The Improving Communication and Teamwork in the Surgical Environment module helps an organization improve teamwork and communication. This module is meant to augment the existing teamwork and communication tools and individual coaching modules of the CUSP toolkit while offering additional strategies to improve teamwork and communication specifically in the surgical environment. Throughout the module, best practices from the ambulatory surgery setting are highlighted.

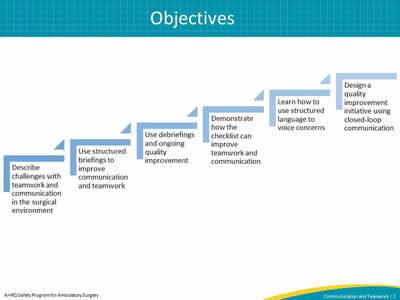

Slide 2:

Say:

This module has several objectives. After this presentation, you should be able to—

- Describe challenges with teamwork and communication in the surgical environment.

- Use structured briefings to improve communication and teamwork.

- Use debriefings and ongoing quality improvement.

- Demonstrate how the checklist can improve teamwork and communication.

- Learn how to use structured language to voice concerns.

- Design a quality improvement initiative using closed-loop communication.

Slide 3: Overview

Say:

In this module, you will learn concrete ways to improve communication and teamwork in the surgical environment. I will first provide an overview of the challenges with communication and teamwork. Then we will discuss these methods to improve teamwork and communication:

- Briefings

- Debriefings

- The Surgical Checklist

- Speaking Up Using Structured Language

- Closed-Loop Communication

Slide 4: Communication and Teamwork Defined

Say:

Let's start with an overview of teamwork and communication.

In this section, we will discuss the meaning of communication, barriers to effective communication, and the impact of poor communication on patient outcomes.

We will then define teamwork and explore poor teamwork's impact on patient outcomes.

Finally, we will learn how team members' differing views on teamwork can impact communication and teamwork in surgery.

Slide 5: Communication Is—

Say:

Getting necessary information to the right people so decisions can be made is the definition of communication we will use today. This involves communication among everyone on the team.

Part of effective communication is briefing and debriefing in order to give information before a team acts. Followup communication after the team completes its job is also crucial.

Later, we will talk in more detail about briefing and debriefing in the surgical environment.

Slide 6: The Problem: Challenges of Effective Communication

Say:

The surgical environment makes communication challenging. Operating and procedure rooms can be chaotic places where background noise makes hearing difficult. Masks cover people’s mouths, which muffles their speech and prevents others from seeing their mouths as they speak. Often, when an instruction is given, it is not clear who is supposed to carry it out.

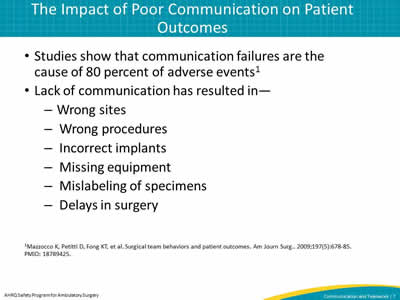

Slide 7: The Impact of Poor Communication on Patient Outcomes

Say:

Given this environment, it is no surprise that communication challenges can harm patients. Communication failures are a frequent cause of patient harm. Studies have found that communication failures are the cause of up to 80 percent of operating room adverse events.

Furthermore, lack of communication has resulted in serious patient safety events such as teams performing a procedure on the wrong site, performing the wrong procedure, using incorrect implants, not having appropriate equipment, mislabeling specimens, and delaying surgery.

The majority of studies to date focus on communication within surgical teams. While there is not a large body of evidence on communication barriers among teams that perform nonsurgical procedures such as endoscopies, we can infer that similar communication errors are prevalent and that patients have been harmed. Good communication leads to improved patient outcomes and is a major component of improved teamwork in the surgical environment.

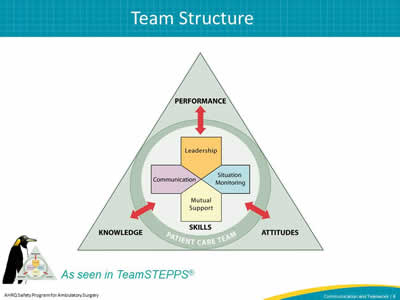

Slide 8: Team Structure

Say:

Team structure refers to the composition of an individual team or of a multiteam system. Team structure is an integral part of the teamwork process. A properly structured patient care team enables and results from effective communication, leadership, situation monitoring, and mutual support.

Proper team structure can promote teamwork by including a clear leader, involving the patient, and ensuring all team members commit to their roles in effective teamwork.

It is important to identify and recognize the structure of teams, because teamwork cannot occur in the absence of a clearly defined team. Further, understanding how a team is structured and how multiple teams interact in a center is critical for planning the implementation of quality improvement strategies. This graphic from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality's or AHRQ's TeamSTEPPS program depicts some of the interactions that occur in care teams. Occasionally throughout this module, other ideas from TeamSTEPPS will be referenced.

Slide 9: High-Performing Teams

Say:

Now let's focus on teamwork.

Ask:

What is teamwork in this environment?

Say:

Teamwork is working together toward a common goal, knowing everyone's roles, respecting people, welcoming and listening to others' views, using available resources to complete the job, understanding what is going on around you and keeping track of the big picture to maintain connections with team members. High-performing teams also—

- Have clear roles and responsibilities

- Have a clear, valued, and shared vision

- a common purpose.

- an engaging purpose.

- a leader who promotes the vision with the appropriate level of detail.

- Optimize resources.

- Have strong team leadership.

- Engage in a regular discipline of feedback

- frequently provide feedback to each other and as a team.

- establish and revise team goals and plans.

- differentiate between higher and lower priorities.

- have mechanisms for anticipating and reviewing issues.

- Develop a strong sense of collective trust, team identity, and confidence.

- manage conflict by effectively engaging one another.

- trust other team members' intentions.

- believe strongly in the team's ability to succeed.

- develop shared efficacy.

- have a high level of psychological safety.

- Create mechanisms to cooperate, coordinate, and generate ongoing collaboration

- ensure that the team possesses the right mix of competencies through staffing and development.

- distribute and assign work thoughtfully.

- consciously integrate new team members.

- involve people in decisions in a flexible manner.

- examine and adjust the team's physical workplace to optimize communication and coordination.

- Manage and optimize performance outcomes

- communicate often and at the right time to ensure that fellow team members have the information they need to contribute.

- use closed-loop communication.

- learn from each performance outcome.

- continually strive to learn.

Slide 10: The Impact of Poor Teamwork on Patient Outcomes

Say:

Poor teamwork causes many problems. Studies show that surgical teams who exhibit fewer teamwork behaviors put patients at higher risk for death and serious complications. So, there is a direct link between teamwork and patient outcomes.

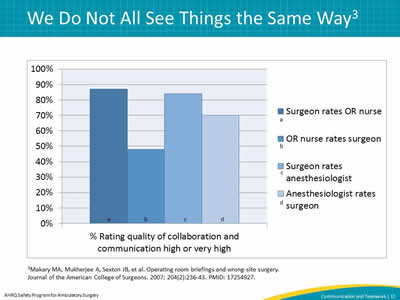

Slide 11: We Do Not All See Things the Same Way3

Say:

As we seek solutions, we should understand that not everyone who works in the surgical environment sees the current level of teamwork the same way. A 2006 study conducted by researchers at Johns Hopkins, “Teamwork is in the Eye of the Beholder,” surveyed 60 operating room team members about their perceptions of teamwork, communication, and leadership in the operating room or OR.

As shown in this graph, 87 percent of surgeons rated the communication and collaboration of OR nurses as high or very high, but only 48 percent of OR nurses gave the same rating to surgeons. There are clearly two different pictures here, almost as if nurses and surgeons do not work on the same team.

The two bars on the right show that this difference in perspective includes anesthesiologists. Eighty-four percent of surgeons rated the communication and collaboration of anesthesiologists as high or very high, while 70 percent of anesthesiologists gave that rating to surgeons.

In both cases, surgeons believed their communication and collaboration with the people around them was at a higher level than those people did of the surgeon.

Before we can start improving communication and teamwork, it is important to have a good understanding of how your coworkers view teamwork and communication. Before you start work to improve communication and teamwork, consider administering a culture survey to better understand how team members view communication and teamwork. One example used by many facilities is the AHRQ Survey on Patient Safety culture. The results will help focus your quality improvement efforts and make the case that the teams in your facility can do even better.

3Makary MA, Mukherjee A, Sexton JB, et al. Operating room briefings and wrong-site surgery. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2007; 204(2):236-43. PMID: 17254927.

Slide 12: Improving Surgical Team Communication With Briefings

Say:

For the rest of the presentation, we will focus on specific ways to improve communication and teamwork in the surgical environment. We will start with briefings.

Slide 13: A Briefing Is a Discussion That—

Say:

Briefings originated in the aviation and nuclear power industries to ensure necessary information was communicated to every team member. These techniques are being integrated into health care through programs such as TeamSTEPPS.

Ask:

What is a briefing in the surgical environment?

Say:

The briefing is a discussion that facilitates clear and effective communication. This discussion puts all team members on the same page before the start of the procedure and helps create a sense of teamwork and collaboration.

A well-performed briefing also creates an environment in which team members speak up if they perceive a problem, because the surgeon or physician invites team members to do so.

Finally, briefings help set the tone for the procedure. If there is open communication at the beginning of the case, team members are more likely to keep communicating with one another.

Slide 14: Historical Perspective: The Orange County Briefing Card at Kaiser Permanente4

Say:

One example of an early preprocedural briefing is the briefing card that the Kaiser Permanente medical system developed in 2003 for its Orange County, CA, hospitals.

The briefing consisted of key information shared among the entire team before the start of the case. One key to the briefing was that every item was written down on cards in every operating room, so memorization was not required.

Use of the briefing card led to a drop in wrong-site surgeries and other adverse events. It also increased staff morale and reduced nursing turnover.

4Shepard S. Teamwork in the OR. The Doctors Company: Patient Safety/Risk Management Strategies. An Ounce of Prevention. 2015. Accessed May 2015.

Slide 15: Briefings Help Us To—

Say:

From the work at Kaiser and other work around briefings since then, we know briefings help surgical teams learn the game plan and get on the same page.

Briefings help teams monitor the situation and raise red flags when needed. They also prevent surprises because information previously memorized is shared among team members.

Briefings have been proven to reduce the number of times a procedure is interrupted to obtain information or act on newly obtained information, such as leaving the room to get equipment or supplies. Through these measures, briefings can help improve patient safety.

Slide 16: Components of a Good Briefing

Say:

Good briefings have several critical components. Team members introduce themselves so that no one is anonymous. The introductions also give team members a chance to speak before the case starts. The simple act of someone saying their name makes them more likely to speak again if necessary. A good briefing incorporates other safety checks the team already performs.

For example, the briefing should incorporate the Joint Commission's Time Out and identification and confirmation of the procedure site and side. This is of great importance in procedures that are side specific.

The surgeon shares the operative plan and difficulties anticipated during the operation, which lets team members prepare for problems.

The anesthesia professional shares the anesthetic plan and airway and other concerns, allowing adequate time for preparation by other team members.

The nurse and scrub technician share any equipment issues or other potential problems. They also confirm that all medications present on the field are correct and labeled.

The briefing is a good time to make sure the size and type of any implant to be used are correct. Finally, the surgeon or physician sets the tone with this statement: “Does anybody have any concerns? If you see something that concerns you during this case, please speak up.”

When you are looking to enhance your briefing or start a briefing in your facility, remember that a good briefing occurs when everyone on the team has a chance to say something before the start of the case. Finally, the briefing should be performed when all team members are present. In the United States, because the surgeon or physician is often not present until the procedure is about to begin, this means the briefing should occur immediately before skin incision or the start of the procedure.

Slide 17: Briefing

Say:

Let’s see what a good briefing looks like. This clip shows a team performing a briefing in an ambulatory surgery center.

Note: This slide includes a video. If you have trouble accessing the video on this slide, it is also available here: https://youtu.be/NhFU4h3aQE4.

Do:

Play the video.

Ask:

What are some of the qualities of a good briefing that you saw? Did you notice that everyone said something? Did you notice that the surgeon set the tone at the beginning of the procedure when he asked team members to speak up if they had any concerns during the case?

Slide 18: Improving Surgical Team Communication With Debriefings

Say:

Let's move to another critical aspect of improving teamwork and communication, which is debriefing at the end of the case.

This is another process from the aviation industry that ensures critical information is exchanged among team members. In this section, we will discuss what a debriefing is and how it can help us in the surgical environment.

We will also discuss the components of a good debriefing and ways to use the information from the debriefing to make changes in your surgical suite. In this section, we will call this idea “continuous quality improvement.”

Slide 19: A Debriefing Is a Discussion Where—

Ask:

What is a debriefing?

Say:

A debriefing is a discussion at the end of the case that all team members participate in, ideally before the patient is transferred to the recovery area.

It gives the team a chance to make a plan for recovery and think about what happened during the procedure and act on any problems that are identified. This discussion can include key concerns for the patient’s recovery, equipment problems encountered, and improvements that would have made the case safer or more efficient.

One of the most difficult components of performing a debriefing is making sure that it occurs when all team members are present. In the presence of an awake or aware patient, the team may have to move the conversation to a later time. We will talk about this in a few minutes.

Debriefings add great value to facilities that use them. They can help identify minor problems that still require attention, as well as more serious problems. The type of debriefing that we will discuss should be used after every case and is focused on fixing everyday problems encountered in the surgical environment, such as wrong instruments or mislabeled specimens. If a serious patient safety event takes place during the case, such as a wrong site surgery, this debriefing may need to be modified, and it may be helpful to utilize other tools and processes. One such tool is AHRQ's Learn From Defects Tool.

Slide 20: Benefits of Debriefing

Say:

Debriefings have several benefits. They bring the team together after the procedure to confirm critical information.

Debriefings let the clinical team pause and discuss what went well or what could have been done better during the case in a safe environment that permits open communication. They can facilitate a discussion of how to solve problems so they do not reoccur.

They can help promote patient safety by reinforcing the importance of discussions that might improve care or the efficiency of the team.

Slide 21: Components of a Good Surgical Debriefing

Say:

When you are considering incorporating a debriefing into your common practice or enhancing your current debriefing process, remember the components of a good debriefing. These include verification of sponge and needle counts, review of the procedure performed so that everyone on the team confirms the procedure is recorded as it was actually done, and confirmation of specimen labeling by reading back the patient’s name to ensure specimens are properly processed.

A good debriefing also includes a discussion about equipment issues or problems identified during the procedure that need to be addressed afterwards. This may include concerns for the patient’s recovery and management so that it travels with the patient to the next place of care. Lastly, there should be a discussion of how the team could provide even better care in the next case.

Slide 22: Debriefing

Say:

Let’s see what a good debriefing looks like. This clip shows a team performing a debriefing in an ambulatory surgery center.

Note: This slide includes a video. If you have trouble accessing the video on this slide, it is also available on the AHRQ Web site here: https://youtu.be/fKmNhVn9R1I.

Do:

Play the video.

Ask:

What are some of the components of a good debriefing that you saw?

Slide 23: Timing the Debriefing Discussion

Say:

In the video, the debriefing was conducted in the room in front of the patient. It is good practice to debrief in the operating room whenever possible. Many surgical operations and procedures are performed with local or regional anesthesia, so the patient is at least partially aware.

The surgical team should judge what is appropriate to share in front of the patient. The underlying principle is that the care team should use common sense in deciding when to discuss serious problems or other issues in front of the patient. Simple problems with equipment can safely be discussed in front of the patient. If team members feel that part of the debriefing discussion cannot be carried out in front of the patient, they should arrange to meet as soon as possible to have the discussion in a safe environment where they can communicate openly.

The value of the debriefing to improve patient care is clear, but not commonly practiced. The biggest hurdle is actually doing the debriefing and doing it well. The longer the surgical team waits to have the debriefing, the greater the likelihood the debriefing will not occur. A debriefing that never occurs cannot benefit subsequent patients. Furthermore, a poorly conducted debriefing that does not enable a safe environment for clinicians to speak freely will actually hinder the clinical team’s ability to deliver safer care in the future.

The debriefing is probably one of the most difficult techniques to incorporate into the surgical environment. At the end of the case, everyone moves to get the patient into the recovery area quickly. Many times the surgeon and/or physician leaves to prepare for another case or take care of another patient. Many facilities that use debriefings start this discussion after sponge counts are completed or when the surgeon removes their gloves. It is also best to assign one team member to initiate this discussion. In many facilities this can be the circulating nurse or the scrub tech.

Slide 24: Problems Identified by Debriefings

Say:

Many facilities across the country and globally have started to use debriefings routinely. These facilities have found the debriefing helpful to identify problems.

The most common problems reported when teams have debriefed at the end of a case include near misses, equipment issues, mislabeling of specimens, and incorrect sponge and needle counts.

Identifying these problems is not enough. Facilities that use debriefings and get the most out of them use them for continuous quality improvement.

Slide 25: Using Debriefings for Continuous Quality Improvement

Say:

To use debriefing for continuous quality improvement, create a system to collect information given in debriefings. Someone should be assigned to monitor the debriefing, collect the information, and actually fix the problems reported. It is also key to communicate with the person or team who reported the problem to let them know its status and the steps that have been or will be taken to fix it.

Fixing problems identified in the debriefing can get physicians and staff to buy into using briefings and debriefings. Often, team members get frustrated when they report problems that do not get fixed. An example is when a surgeon keeps receiving the same pair of dull scissors. Facilities that use debriefings have reported increased engagement of all team members, including physicians.

Slide 26: The Surgical Checklist as a Communication and Teamwork Tool

Say:

When done properly, briefings and debriefings are two of the most valuable ways to improve communication and teamwork.

One of the best ways to put briefings and debriefings into effective use is through a surgical checklist. The next part of this presentation will focus on what a surgical checklist is and how it can be used as a vehicle for briefings and debriefings.

I will also give examples of checklists that incorporate briefings, debriefings, and essential process checks that should be completed for every patient every time.

Slide 27: The Surgical Checklist

Say:

The surgical checklist was designed to improve communication and teamwork in the surgical environment. It has roots in the Orange County briefing card mentioned earlier. The checklist integrates process and communication items into one tool to ensure that team members communicate necessary information with each other and perform essential safety steps for every patient undergoing surgery.

The checklist requires the team to stop at three critical points for safety review:

- Before induction of anesthesia or before the patient enters the OR.

- Before skin incision and before the start of the procedure.

- Before the patient leaves the room.

Finally, the checklist is designed to be used by the entire team and not only one team member. It should be read aloud from a hard copy. Team members should never memorize the checklist.

Slide 28: Benefits of the Checklist

Say:

The checklist can help in many ways in the surgical environment, including improving communication. It enhances communication among team members and it helps everyone raise awareness and focus on what is going on in the room. When using the checklist effectively, team members set a positive tone as they participate in the checklist. All of these things improve teamwork.

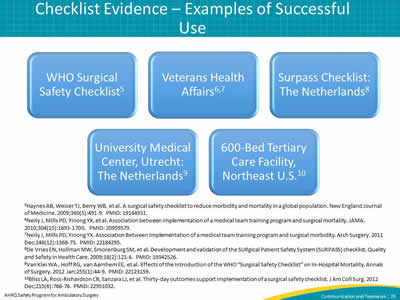

Slide 29: Checklist Evidence – Examples of Successful Use

Say:

Significant evidence supports the use of the surgical safety checklist, and actually shows that the benefits of performing a checklist are enhanced when combined with medical team training.

The first study listed is the original pilot study of the World Health Organization or WHO Surgical Checklist. This study demonstrated a relationship between use of the checklist before surgeries in eight sites around the world and positive results after surgery. Both complications and mortality from surgery decreased at nearly every site.

Additional studies listed here have all demonstrated similar decreases in complications and often in mortality.

As evidence accumulates, a strong evidence base exists in many environments. While the first study focused primarily on environments in the developing world paired with evaluation and use of the checklist in the developed world, more recent studies have examined the use of the checklist in sophisticated medical settings including the Netherlands and the United States.

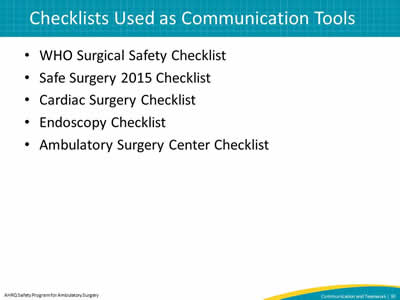

Slide 30: Checklists Used as Communication Tools

Say:

The checklist can be used as a communication tool, and many checklists include briefings and debriefings.

The WHO Surgical Safety Checklist was developed to work in any setting. All communication items on this checklist can be used in any facility in developed or developing countries, but it is not specifically made for use in the United States and developing countries. For example, it does not reflect some of the U.S. standards of practice, like venous thromboembolism prophylaxis.

The Safe Surgery 2015 Checklist was developed specifically for use in U.S. facilities. On this checklist, teamwork and communication elements have been enhanced to include elements specific to U.S. hospitals. This version of the checklist also includes items recommended by the Surgical Care Improvement Program and The Joint Commission.

The cardiac surgery checklist was developed for use in cardiac procedures in the United States because cardiac operating rooms have different requirements from a general operating room.

The endoscopy checklist was developed to address the requirements of an endoscopy procedural area.

Finally, there is the ambulatory surgery center checklist for use in an ambulatory surgery center, or ASC. This checklist includes critical elements needed in the fast-paced environment of an ASC. Let’s look a little closer at the ASC checklist to see how the briefing and debriefing are incorporated.

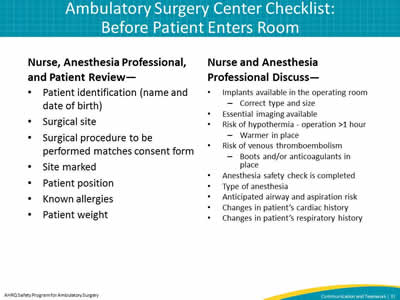

Slide 31: Ambulatory Surgery Center Checklist: Before Patient Enters Room

Say:

The ASC checklist contains elements meant to improve both teamwork and process performance. Each section of the checklist has specific elements aimed at improving both.

Here, you can see the “before the patient enters the room” portion of the checklist suggested for use in ambulatory surgery settings. It is at this point that the nurse and anesthesia professional discuss necessary information with the patient and talk to each other about the patient’s history and needs. This is also the time that the nurse and anesthesia professional can confirm that implants and imaging are available if necessary.

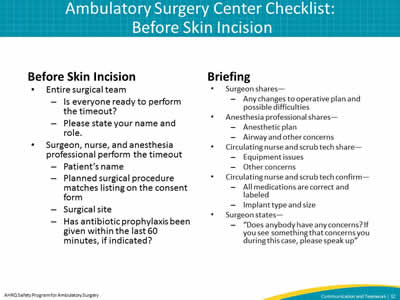

Slide 32: Ambulatory Surgery Center Checklist: Before Skin Incision

Say:

Here, you can see the “before skin incision” portion of the checklist suggested for use in ambulatory surgery settings. This portion of the checklist is designed for the team to use immediately before skin incision or the start of the procedure. Many facilities in the United States are required to stop at this point in care to perform essential safety steps to verify patient identity, procedure, and procedure site. Let’s talk about each of the items included in this portion of the checklist.

Getting the entire team to stop all activity at this point in the case can sometimes be difficult. It is important for all team members to stop what they are doing and actively participate in this discussion. One member of the team should lead this portion of the checklist and initiate this discussion by asking everyone the question “Is everyone ready to perform the timeout?”

Asking if the team is ready to perform the timeout encourages everyone to stop other activities and helps set a positive tone by asking team members if they are ready instead of telling them to stop, which is what typically occurs in facilities in the United States. As you can see, this checklist template does not dictate which team member initiates this portion of the checklist. This is intentionally vague so each facility can designate which team member is responsible for starting this portion of the checklist discussion. In some facilities the nurse leads this portion of the checklist, and other facilities may find it helpful for the surgeon or physician to initiate this discussion.

The next item on the checklist is, “Please state your name and role.” As we previously discussed, having everyone in the room introduce themselves by name and role gives team members a chance to speak before the case starts. The simple act of someone saying their name makes them more likely to speak again if necessary.

The next portion of the checklist incorporates those essential verifications of patient identity, procedure to be performed, and procedure site. This section also includes an item to prompt the team to discuss antibiotic prophylaxis administration, and if it is needed, confirmation that the prophylaxis is completely infused.

Now, let's take a closer look at the elements in the briefing section that are designed to improve teamwork and communication. During the briefing, the surgeon shares changes to the operative plan and the possible difficulties. This is important because it can reveal information not always apparent in information from surgical nurses, surgical technicians, and anesthesiologists. Similar sharing is encouraged from the anesthesia professional, the circulating nurse, and the scrub technician.

Finally, during the briefing the surgeon reads a statement that encourages everyone to speak up if they see anything that might affect the care of the patient. The surgeon’s statement is, “Does anybody have any concerns? If you see something that concerns you during this case, please speak up.”

Slide 33: Ambulatory Surgery Center Checklist: Before Patient Leaves the Room

Say:

At the end of the case, the checklist prompts the team to have a discussion that includes process measures for every patient, including counting the instruments, sponges, and needles, and confirming counts with all team members.

The name of the procedure is accurately recorded because it is discussed with all team members. Sometimes an operation is different from the one initially planned. All team members should know that information before they leave the operating room so it can be recorded accurately in the patient's record.

Finally, specimen labeling is important for procedures where specimens are obtained.

A debriefing is also included in this final portion of the checklist before the patient leaves the operating room.

During the debriefing, the team pauses again to discuss important issues and seeks input from all team members. The team starts this portion of the discussion by talking about any equipment problems that may need to be addressed.

The team should then discuss the key concerns for the patient’s recovery and management so that the patient makes a safe transition to the recovery room.

Finally, there should be an opportunity to improve what happened in every case by asking and seeking information concerning ways to improve the safety and efficiency of the procedure that was just finished.

Slide 34: Customizing the Surgical Checklist

Say:

In this section we will describe essential steps when implementing a surgical checklist or changing a checklist already in place. These steps include—

- Building an implementation team.

- Modifying your checklist.

- Testing your checklist outside of the patient environment using a tabletop simulation.

- Testing your checklist in actual cases.

Slide 35: Building an Implementation Team

Say:

One of the most important tasks when beginning this work is building an implementation team. This team should have at least one representative from each position the checklist potentially affects. Perspectives from every discipline that works in the surgical environment will be needed to make sure the checklist works for your facility and to gain the necessary buy-in. The team should include at least one—

- Administrator

- Surgeon/physician

- Anesthesia professional

- Nurse

- Scrub technician

Often we forget to include an administrator on these types of teams. An administrator will play a key role because they likely can provide resources for projects. They also can update facility leadership on the project's progress and/or barriers.

Physicians are also a key component. Physicians might not have a lot of time, but it is important to identify one willing to participate meaningfully. The physician may not be able to attend every meeting, but can help you modify and test your facility checklist. It will also be helpful to have a physician help engage other physicians when it is time to implement the checklist more widely.

Make sure that your implementation team also includes an anesthesia professional. This can be an anesthesiologist or a CRNA (nurse anesthetist).

Finally, a nurse and a scrub technician are key roles on the implementation team. Both the nurse and the scrub technician have an important role in the checklist and their feedback is important in customizing the checklist so that it meets the needs of all team members.

Slide 36: Things To Consider When Customizing Your Checklist

Say:

Every checklist needs to be customized for the facility. This promotes ownership of the resource. At a minimum, add your facility name and logo to your checklist.

When modifying your checklist, think about the types of cases your team performs, your patient population, and any special needs your facility may have.

When customizing the checklist, remember it is a series of discussions the team performs and that the checklist should be read from a hard copy and not memorized.

Finally, do not make your checklist too long. For an uncomplicated procedure, each section of the checklist should take less than 2 minutes to perform. When facilities have put the checklist into place, the checklist tends to grow. Every item needs to be carefully analyzed before it makes it onto your checklist. On the next slide, we will show questions your implementation team should discuss when you add or remove an item. Successful checklists should be clearly written, concise, and accurate.

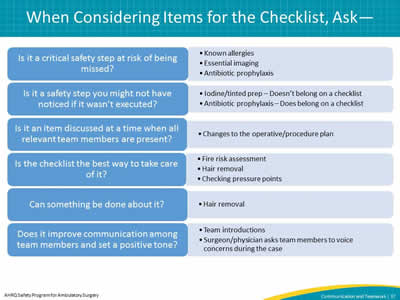

Slide 37: When Considering Items for the Checklist, Ask—

Say:

Here are some critical questions you should discuss with your implementation team when adding or removing items from the checklist.

First, “Is this a critical safety step at the risk of being missed?” We want to minimize the risk to the patient as much as possible, but teams can miss critical safety steps in the complicated surgical environment. Documenting known allergies, doing essential imaging, and administering antibiotic prophylaxis are examples of steps at risk of being missed.

The next question is, “Is this a safety step you might not notice if it isn't done?” This space on your checklist should be reserved for items the team might not notice if they were not performed. Doing iodine/tinted prep is an example of an item that is not relevant for a checklist because the team can see if the prep is on the patient because of its coloring. Antibiotic prophylaxis is a good candidate for a surgical checklist because the team cannot see if the antibiotics have been given, so the checklist provides a reminder to complete that step. To ensure antibiotics are completely infused, the anesthesia professional must communicate this information to the team. If missed, not giving antibiotics to the patient can cause serious harm to the patient.

The third question is, “Is this an item discussed at a time when all relevant team members are present?” It is important to discuss items at a time when those who must be part of the conversation are present. For example, the team should not discuss the operative/procedure plan when the surgeon/physician is not present.

The fourth question is, “Is the checklist the best way to take care of it”? The checklist is not the ideal way to take care of everything. Make sure there are not better ways to address the items you are considering including in your checklist. While some facilities include fire risk assessment, hair removal, and checks of pressure points on their checklists, other facilities have found other processes and tools to take care of these things.

The fifth question is, “Can something be done about it?” Timing is everything with the checklist. The items should be discussed at a time when something can be done about it. For example, the checklist will not be an effective prompt for the team to discuss hair removal after the hair has already been removed.

Finally, the implementation team should discuss whether the item improves communication between team members and sets a positive tone. These are usually the most difficult items for teams to perform consistently, and they are the most commonly removed items when facilities modify their checklist. If you remove these items, make sure the concepts behind each of them are included in your checklist in another way.

Slide 38: Testing Your Checklist Outside of the Patient Environment Using Tabletop Simulation – Part One

Say:

When implementing the checklist in your facility or changing your existing checklist, the first thing to do before bringing it into the surgical environment is to test it using a tabletop simulation.

During the tabletop simulation, team members should sit down around a table, take a role, and walk through it to make sure their checklist works for their facility and that it prompts the team to discuss necessary information for every patient undergoing a procedure. The place to figure this out is not in the surgical environment, but outside of it. We change many things without testing only to find out that the change didn’t work. Testing the checklist outside the surgical environment helps you identify potential changes on the checklist without making mistakes in front of the patient or causing harm.

Say the words on the checklist out loud. Pretend you’re in a real case. Do a full simulation. You don’t need a fancy simulator. You can pretend you’re in an operating or procedure room. Many times words that make sense on paper don’t reflect what you do in your center, and that won’t be obvious until somebody says them. Say them outside the surgical environment. After you go through your checklist, talk about changes before you use it with a patient.

Slide 39: Example of a Tabletop Simulation Part One

Say:

Now, let’s look at what a tabletop simulation looks like.

Note: This slide includes a video. If you have trouble accessing the video on this slide, it is also available on the AHRQ Web site here: https://youtu.be/V_nU8WxCH2w.

Do:

Play the video.

Ask:

Did you notice that each person took a role to play and read through the checklist as if they were actually in a procedure? Why might this be important?

Slide 40: Testing Your Checklist Outside of the Patient Environment Using Tabletop Simulation – Part Two

Say:

One of the most important steps in performing a tabletop simulation is the discussion that occurs after you run through it. This is a chance for everyone to talk about what they think should be changed and how it felt to use the checklist.

Slide 41: Example of a Tabletop Simulation Part Two

Say:

Now, let's see what the last part of the tabletop simulation looks like when the team talks about how it felt to say the words on the checklist and what might need to be changed for their facility.

Note: This slide includes a video. If you have trouble accessing the video on this slide, it is also available on the AHRQ Web site here: https://youtu.be/FY1ZgmC4oJU.

Do:

Play the video.

Ask:

Can you see the benefit of performing a tabletop simulation when your facility is putting a tool like the checklist in place?

Slide 42: Testing Your Checklist in the Patient Environment

Say:

After you modify and test your checklist, the next step is to test it in a case. Start by testing with one team for one case. When you are first testing the checklist in the clinical environment, test the checklist initially with checklist implementation team members.

If you can't test the checklist with implementation team members, test it with a supportive physician. If you test the checklist with individuals who haven't been previously exposed to the checklist, remember to train everyone how to use it before they try it with a patient. You might need to meet with them beforehand and walk through the checklist together.

Always have an implementation team member in the room to collect feedback about changes. Then modify the checklist as necessary.

The next step is to test the checklist with one team for one day and modify as necessary. The process of testing with teams and modifying the checklist can be repeated multiple times with the same team or with different teams to ensure the checklist works before it is finalized.

Slide 43: Speaking Up Using Structured Language

Say:

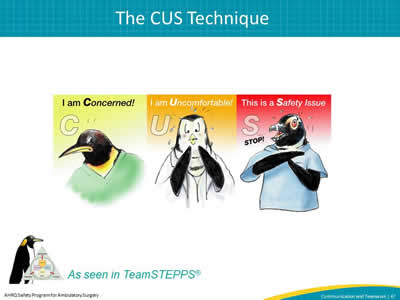

In this section, we will discuss how to improve communication by helping people speak up when they see something that concerns them. We will discuss the importance of voicing concerns in the surgical environment and barriers to speaking up. The solution is structured language using the CUS technique, which we will listen to some examples of. This technique is taught in many quality improvement initiatives, including AHRQ’s TeamSTEPPS.

Slide 44: Why Voicing Concerns in the Surgical Environment Is Important

Say:

Studies show that many times when adverse events occur in the surgical environment, someone knew something was about to happen but did not speak up. Reported problems include wrong-site surgeries, wrong procedures, wrong or missing implants, wrong medications, unidentified allergies, and/or wrong equipment. Patients are harmed unnecessarily, and health care providers can deliver safer care to prevent these events.

Slide 45: Barriers to Speaking Up

Say:

Many barriers keep people from speaking up. These include fears of being embarrassed, feeling stupid, being ridiculed, being yelled at, being wrong, or saying something that might not be important. Many people think someone won’t listen to them when they speak up or that it’s not important.

Ask:

How do we change this?

Slide 46: The Solution: Structured Language

Say:

A potential solution is the use of structured language. Its use is standard practice in many high-risk industries and on high-performance teams. In structured language, specific agreed-upon words indicate a problem. These words act as flags to signal that something in the room is of concern or is dangerous to the patient.

Structured language works best when both the sender of the information and the receiver of the information understand the words. We are going to use “CUS” to indicate safety concerns, but other words are also used. For example, in some hospitals, the word “clarity” is used instead of “concern.”

Slide 47: The CUS Technique

Say:

A feature of structured language is escalating speech that gradually indicates increasing levels of concern. Escalating speech is better received than “STOP” when something is of concern. When the conversation starts with “STOP,” emotions are triggered and the situation is made worse. Structured language lets people voice their concerns without being extreme.

Here are examples of escalating speech:

- "I am concerned" or "I need clarity." This is equivalent to a red flag going up.

- "I am uncomfortable." The red flag is waving.

- "Stop." This indicates a safety issue. This is the extreme. If the problem reaches this point and nothing changes, there should be a plan for the next step in this situation.

Slide 48: Examples of Speaking Up

Say:

Let's listen to two examples of what speaking up in the OR sounds like.

Note: This slide includes an audio recording. If you have trouble accessing the audio on this slide, it is also available on the AHRQ Web site here: https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/hais/tools/ambulatory-surgery/sections/implementation/training-tools.html.

Do:

Play audio clip.

Slide 49: Closed-Loop Communication

Say:

Another way to improve communication is closed-loop communication. We will discuss how closed-loop communication enhances team communication and we’ll listen to an example of closing the loop in the surgical environment.

Slide 50: The Solution: Closed-Loop Communication

Say:

Closed-loop communication is another way to improve the team’s ability to exchange clear and concise information. In closed-loop communication, we acknowledge receipt of information, and then we confirm we understood what the information means.

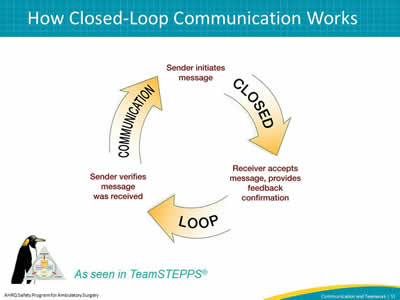

Slide 51: How Closed-Loop Communication Works

Say:

This slide is taken from TeamSTEPPS. Here, closed loop is called by its other name – check-back.

The sender begins by initiating the message and passing it to the receiver, who demonstrates acceptance of the message and gives feedback that message has been received. Finally, the sender verifies with the receiver that the message has been received.

Slide 52: Closed-Loop Communication Example

Say:

Let's listen to examples of closed-loop communication in the surgical environment. This is an audio clip demonstrating how closed-loop communication can be used clinically.

Note: This slide includes an audio recording. If you have trouble accessing the audio on this slide, it is also available on the AHRQ Web site here: https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/hais/tools/ambulatory-surgery/sections/implementation/training-tools.html.

Do:

Play audio clip.

Slide 53: Summary

Say:

In summary, improving teamwork and communication can lead to better patient care. In this presentation we have discussed several ways to do this, including—

- Conducting team briefings before every case ensures that all team members have the essential information needed to take care of the patient.

- Having the entire team pause at the end of a case to discuss a plan for the patient and talk about anything that could be done better for the next case.

- Implementing a surgical checklist can help facilities improve communication and teamwork. The checklist is a vehicle to bring briefings and debriefings to the surgical environment.

Teaching team members structured language like CUS and closed-loop communication can lead to improved teamwork and communication.

Improving team communication is not an easy fix and requires patience and time. However, if you are persistent, there is tremendous benefit for the patients we care for every day and for our fellow team members.

Slide 54: Tools

These tools discussed in this module may help you implement these ideas. These include—

- The checklist demonstration video

- The closed-loop audio recording

- The CUS technique

- Examples of checklists, including the ambulatory surgery center checklist, the cardiac surgery checklist, the endoscopy checklist, the Safe Surgery 2015 checklist, the WHO surgical safety checklist, and TeamSTEPPS Briefing and Debriefing Checklists.

- The speaking up technique

- The tabletop simulation process

Slide 55: References

- Mazzocco K, Petitti D, Fong KT, et al. Surgical team behaviors and patient outcomes. Am Journ Surg. 2009;197(5):678-85. PMID: 18789425.

- Salas E, Burke CS, Stagl KC. Developing teams and team leaders: Strategies and principles. In: Demaree RG, Zaccaro SJ, Halpin SM, editors. Leader development for transforming organizations. April 2004 as cited in: TeamSTEPPS Fundamentals Course: Module 1. Introduction. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; March 2014.

- Makary MA, Mukherjee A, Sexton JB, et al. Operating room briefings and wrong-site surgery. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2007; 204(2):236-43. PMID: 17254927.

- Shepard S. Teamwork in the OR. The Doctors Company: Patient Safety/Risk Management Strategies. An Ounce of Prevention. 2015. Accessed May 2015.

- Haynes AB, Weiser TJ, Berry WB, et al. A surgical safety checklist to reduce morbidity and mortality in a global population. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;360(5):491-9. PMID: 19144931.

- Neily J, Mills PD, Yinong YX, et al. Association between implementation of a medical team training program and surgical mortality. JAMA. 2010;304(15):1693-1700. PMID: 20959579.

- Neily J, Mills PD, Yinong YX. Association Between Implementation of a medical team training program and surgical morbidity. Arch Surgery. 2011 Dec;146(12):1368-73. PMID: 22184295.

- De Vries EN, Hollman MW, Smorenburg SM, et al. Development and validation of the SURgical Patient Safety System (SURPASS) checklist. Quality and Safety in Health Care. 2009;18(2):121-6. PMID: 19342526.

- Van Klei WA , Hoff RG, van Aarnhem EE, et al. Effects of the Introduction of the WHO “Surgical Safety Checklist” on In-Hospital Mortality. Annals of Surgery. 2012 Jan;255(1):44-9. PMID: 22123159.

- Bliss LA, Ross-Richardson CB, Sanzara LJ, et al. Thirty-day outcomes support implementation of a surgical safety checklist. J Am Coll Surg. 2012 Dec;215(6):766-76. PMID: 22951032.

- Safe Surgery 2015. Ariadne Labs. Accessed July 2013.

- World Health Organization Surgery Checklist. Accessed July 2013.

- Pocket Guide: TeamSTEPPS. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; January 2014.

- Learn From Defects Tool. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; December 2012.