Agency investments in primary care research between 1990 and 2020 took the form of grants, contracts, and intramural projects to develop tools, conduct research, and develop conceptual frameworks and research agendas. Grant investments included Agency-directed Requests for Application (RFAs) and investigator-initiated grants, and covered a wide range of grant types: R01 (large research project), R03 (small research project), R18 (demonstration and dissemination), R21 (exploratory/developmental research), R24 (resource-related research project), R36 (research dissertation program), R13 (conference grant), U grants (cooperative agreements), P grants (research program project grants, exploratory grants, center core grants), K grants (new investigator grants), and F grants (individual fellowships). Between 2008 and 2019, 29% of all primary care research awards went to R18s, 19% to R01s, and 10% to R03s.

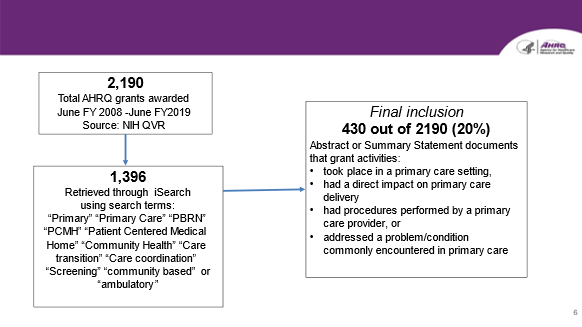

The primary care research grant investments from 2008-2019 totaled approximately $218 million and crossed the lifespan and continuum of primary care, represented diversity in populations, including minority and priority populations, and involved many different regions of the country. From fiscal year 2008 through 2019, AHRQ funded 430 primary care research grants out of 2,190 grants awarded over this time period. Thus, almost 20% of all funded AHRQ grants were primary care research (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Primary Care Grants Identified 2008-2019

Data on primary care research contracts and intramural research were more difficult to tease out due to the variety of mechanisms and funding sources over time, but contracts for primary care research awarded through the ACTION network alone totaled more than $22 million between 2009 and 2019.

Foundational Themes on AHRQ's Primary Care Research: Infrastructure, Methods, and Data

Over 30 years, AHRQ has worked to build the national capacity to conduct primary care research through building the human and institutional infrastructure needed for primary care research, advancing the methodology of primary care research, and creating data resources to describe and measure primary care.

Research Infrastructure

Nurturing a Cadre of Primary Care Researchers

Ensuring a supply of well-trained primary care researchers was part of AHCPR's first primary care research agenda 4. Paul Nutting, the first Director of the Division of Primary Care for AHCPR, described the Agency's early commitment to developing primary care researchers with specific expertise in health services research, a relatively new field in the 1990s—"primary care research to this point focused on clinical studies—what treatment works for different problems—but we saw the greatest need for building researchers who were focused on service delivery in the context of healthcare practice." The IOM echoed the need for developing and nurturing primary care-focused health service researchers in their 1996 report, Primary Care: America's Health in a New Era, explaining that the need for such researchers had "outstripped the current supply."1

To meet this need, AHCPR established a task force to build capacity for research in primary care in the early 1990s,13 which led to ACHPR funding for education and training for primary care clinicians and researchers in skills such as institutional review board (IRB) submissions, grant writing, research design, methodology, and analysis.14 AHRQ has continued to fund numerous visiting scholar positions, research sabbaticals, new investigator awards, student and training grants, and training programs, including 34 F and K awards between 2008 and 2019.

ACHPR/AHRQ also supported numerous conferences and workshops where primary care researchers could network, collaborate, and disseminate their work to move the field forward. Examples of primary care research conferences supported by AHRQ in the past ten years include: the North American Primary Care Research Group Annual Meeting, Working Conference Series to Disseminate Patient Centered Medical Home Implementation Strategies; Primary Care, Prevention and Screening Research for People with Intellectual Disabilities; Integrated Care for Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders: Making Research Work to Improve our Health; multiple practice-based research conferences, and the 30th Anniversary Primary Care Research Conference held in December 2020.

AHRQ's direct and indirect support of these conferences and workshops was vital. Primary care researcher and medical anthropologist, Benjamin Crabtree, from Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, explained that "scores of primary care researchers got their start with AHRQ, grew up with AHRQ, and flourish thanks to the support of AHRQ." He, for example, received an AHRQ R13 conference grant to support a Methodological Think Tank15 held in conjunction with the annual AHRQ-funded Primary Care Research Methods & Statistics Conference in 1993. This Think Tank led to the publication of a book: Exploring Collaborative Research in Primary Care.16 Dr. Crabtree went on to receive additional funding from AHRQ, NIH, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and others for primary care research. He worked with ESCALATES, the national evaluation of AHRQ's EvidenceNOW: Advancing Heart Health initiative.17

Connecting Practitioners and Researchers: The Practice-Based Research Networks

In addition to training and supporting primary care researchers, AHRQ has played an important role in primary care practitioners and researchers. In 1997, Lanier and Clancy13 emphasized the "pressing need for sustainable infrastructures that link practitioners and researchers in an effective fashion." They also hypothesized that involving multiple clinical sites in research would lead to more generalizable research that takes less time from conceptualization to publication. AHRQ's work to develop and support the Practice-Based Research Networks (PBRNs) helped put this vision into practice for primary care research.

PBRNs are groups of ambulatory practices devoted principally to the primary care of patients and affiliated in their mission to investigate questions related to community-based practice and to improve the quality of primary care. Put simply, they are "clinical laboratories for primary care research and dissemination."18 The history of PBRNs in the U.S. dates to the 1970s, when two regional PBRNs were formed: the Cooperative Information Project and the Family Medicine Information System in Colorado.19 PBRNs gained in number and productivity throughout the 1980s and 1990s, and were recognized by the IOM as "a significant underpinning for studies in primary care."1 Despite this recognition of their importance, PBRNs struggled to get resources. At a time when funding for PBRN work was hard to come by, AHCPR sponsored approximately ten PBRN research studies prior to 2000, including the Child Abuse Reporting Experience Study (CARES) (R01, PI: E. Flaherty)20 and early work related to medical errors and telephone care for Medicare patients.

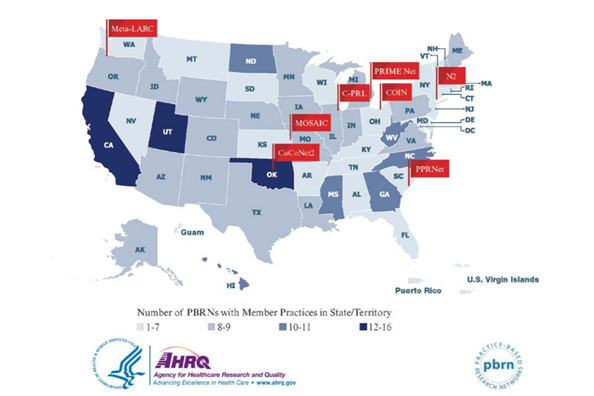

The Agency's role in PBRNs expanded after 2000, when David Lanier, then part of the Center for Primary Care at ACHPR, made the case for expanding opportunities for primary care PBRNs.21 In response, ACHPR released a funding request for PBRN planning grants, for which more than 100 applications were received and 19 were funded. Dr. Lanier describes the response as "amazing and overwhelming" and the impact as "galvanizing the primary care community." Between 2000 and 2010, AHRQ funded six competitive grant series and more than 40 contracts specific to PBRN work (totaling more than $20 million). PRBNs also received support through other AHRQ investments (e.g., health IT grants, American Recovery and Reinvestment Act). In 2012, AHRQ launched an initiative to support eight collaborative centers for primary care practice-based research through five-year P30 program grants. These centers, which came to be known as the Centers for Primary Care Practice-Based Research and Learning, were comprised of multiple PBRNs with at least 120 member practices each (Figure 4). AHRQ also began funding an annual PBRN International Conference where members could meet to share ideas and research, network, and learn from one another.

Figure 4. The Centers for Primary Care Practice-Based Research and Learning

Sustained funding of the PBRNs and the Centers allowed a surge of activity in frontline primary care research, methods, and tools, such as:

- Creation of a national Practice Facilitator Professional Development and Training Program and Practice Facilitation Handbook that was instrumental in Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH) transformation and continues to be used broadly for primary care quality improvement.

- Establishment of the National Center for Pediatric Practice-Based Research and Learning focused on improving delivery of and learning from pediatric primary care throughout the U.S. and training of junior primary care researchers.

- Adaptation and evaluation of research methodology to primary care in areas such as community-led patient-centered outcomes research, quality improvement,22 rapid cycle research, clinical trials,23 the RE-AIM (reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, maintenance) framework, the Pragmatic-Explanatory Continuum Indicator Summary (PRECIS),24,25 Clinical Inquiries (Clin-IQ) PBRN best practices.26-28

- Training researchers to conduct primary care research in PBRNs through a certificate program in practice-based research methods.

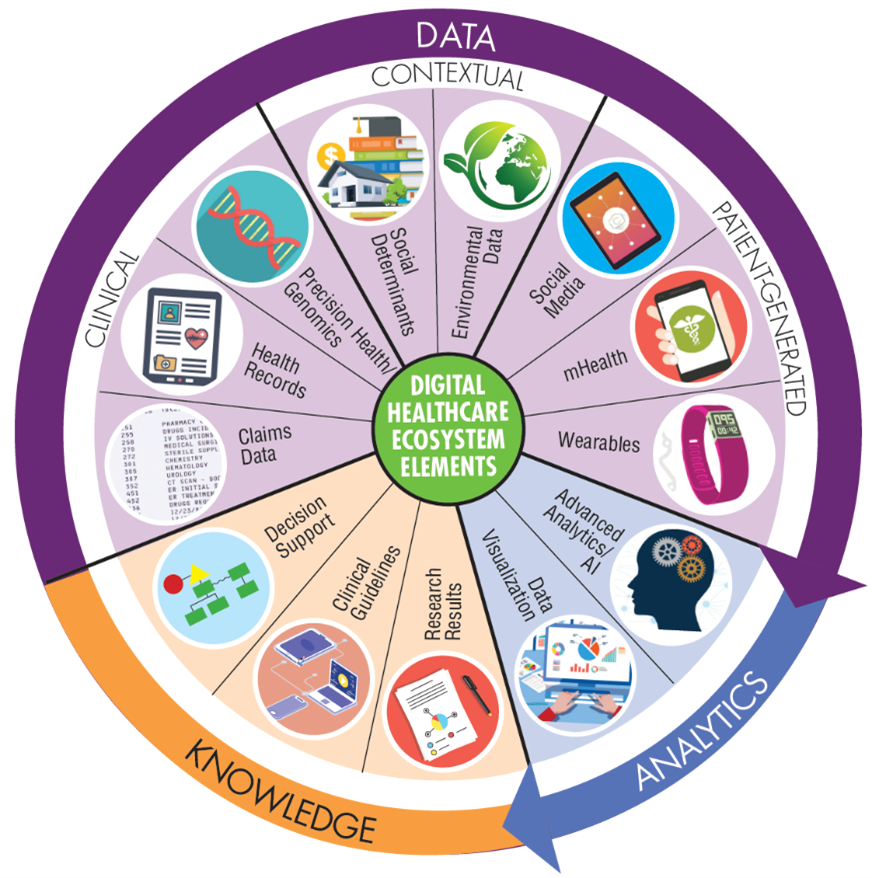

- Innovative use of digital healthcare in research and clinical practice; for example, development of an electronic health record (EHR) functionality and structure to improve care to pediatric patients, and the impact of digital healthcare on practice performance29 and patient safety.30

- Numerous continuing education opportunities for clinicians, including conferences, workshops, webinars/seminars, and more than 750 online CME courses.

Despite stepping back from direct funding due to budget limitations, as of July, 2020, AHRQ continues to host PBRN resources, a PBRN Registry, and fund the annual PBRN International Conference.31 PBRNs have fostered the culture of applied, practice-base health services research throughout the primary care system.19 PBRN pioneers, Larry A. Green and John Hickner, wrote that "it would be difficult to overstate the importance of AHRQ in the maturation of practice-based research in the United States."19 This culture, and the skills and relationships that support it, placed PBRNs at the center of many local responses to COVID-19, providing telemedicine resources, community health center support, and learning communities related to the pandemic.32,33 It has been estimated that one third of Americans are reached by at least one PBRN.34

Methods for Primary Care Research

To conduct high-quality research that impacts primary care, appropriate research methods must be available and utilized correctly. To that end, AHRQ has contributed to the development and use of research methods that have accommodated that goal. Here are some ways AHRQ has enhanced research methods.

First, AHRQ staff remains up to date on new and emerging research methods and has encouraged the use of specific methods in their calls for proposals. This has facilitated the application of research methods in AHRQ-funded studies adding to the evidence base. Some examples include the importance of stakeholder engagement methods in research (RFA-HS-19-002 Using Data Analytics to Support Primary Care and Community Interventions to Improve Chronic Disease Prevention and Management and Population Health) or innovative study designs (RFA-HS-14-008 Accelerating the Dissemination and Implementation of PCOR Findings into Primary Care Practice).

Second, AHRQ has invested in the development of new methods and has curated reports outlining methods recommendations. For example, in the Effective Healthcare Programs, guidance can be found on use of methods.

Third, AHRQ has provided methods training in the form of webinars on specific research methods, as well as resources for methods information including reports and tools. Additionally, AHRQ has funded conference grants that have furthered primary care methods, such as the San Antonio Primary Care Research Methods and Statistics Conference that ran for from 1995 through 2005 and the more recent Colorado Pragmatic Research and Health Conference (2020).

Related to methods is the development of metrics and measures in which to determine the success of primary care research on important outcomes. In addition to the data sources, measures have included development and support for the CAHPS surveys, which are endorsed by the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA). These surveys have been used to design quality improvement initiatives in more than 300 research studies, and informed the development of other patient-focused surveys. Two examples include studies to assess survey response rate when patients are offered the possibility of a small monetary reward35 or are presented with web-based vs. print surveys.36 Cultural differences in responses to care scenarios and sample vignettes were also evaluated.37 Other examples include the COmputerized Needs-oriented QUality measurement Evaluation SysTem (CONQUEST 2.0) and the Quality Measures project (Q-Span). These were early (1990s) quality improvement software tools that aimed to promote clinical performance measurement standardization in primary care and other settings.14,38

The Informed Consent and Authorization Toolkit for Minimal Risk Research toolkit helps both researchers and institutional review boards ensure that potential subjects can make well-informed decisions about participating in research studies. The Toolkit includes model process for obtaining written consent and authorization, sample easy-to-read consent documents for informed consent and authorization, and a certification tool to promote the quality of the consent process.

"I think of the Alternative Quality Contract in Massachusetts… was possible because of a variety of different AHRQ-funded research on quality metrics, capitation payments, global payments, pay-for-performance. You know, these components end up allowing the design of potentially game-changing delivery system innovations, payment system innovations."

–RAND interviewee

Data for Primary Care Research

Accurate and accessible data is the bedrock of research. AHRQ is the home for several of the databases regularly used to describe, measure, and evaluate primary care in the U.S and has played an integral role in standardizing key measures and indicators.

Since 2003, AHRQ has produced the National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report (NHQDR), which presents data on more than 250 healthcare quality measures in both chartbooks and interactive form. While not exclusively focused on primary care, the measures can be filtered for primary care and include several measures of high relevance to primary care research such as access to care, patient centeredness, and whether standards for screening and treatment are being met for typical primary care conditions.

In 2008, AHRQ introduced primary care versions of the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) surveys of patients' healthcare experiences—CAHPS-Adult Primary Care 1.0 and CAHPS-Child Primary Care 1.0. A Clinician & Group version, CG-CAHPS, was also developed and is used in primary care. CAHPS surveys, which are endorsed by the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA), have been used to design quality improvement initiatives, in more than 300 research studies, and informed the development of other patient-focused surveys.35,36

Another well-known AHRQ data initiative is the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), formerly called the National Medical Expenditure Survey (NMES). MEPS, a set of large-scale surveys of families and individuals, their medical providers, and employers, has been broadly used by primary care researchers. For example, research out of Harvard, the Center for Primary Care, and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement used MEPS data to develop a tool to gauge how workforce and financing changes impact multiple aspects of primary care. One Technical Expert Panelist interviewed for RAND's Health Services Research and Primary Care Research Report (2020) emphasized MEPS national impact, stating, "…if MEPS did not exist, the Congressional Budget Office couldn't do its job. The sort of stuff that [a health coverage expert] does, she couldn't do her job. You know, all the people who are trying to do sort of health simulation and health policy stuff, without MEPS, that's not possible."

In 2019, AHRQ launched a $6 million grant initiative: Empowering Primary Care Using Data and Analytics to Build a Healthier America to improve the application of data in primary care research. Three grantee teams examined how to integrate data on chronic disease, social determinants of health, and community services to increase the capacity of primary care practices to deliver "whole-person care" and to better manage the populations they serve.

Topics in Primary Care Research

Organization of Care

In 2001, the IOM Committee on Quality of Healthcare in America issued a report, Crossing the Quality Chasm, that made an "urgent call for fundamental change to close the quality gap" through a "sweeping redesign of the American healthcare system."39 Since that time, AHRQ has made numerous investments to learn how to redesign and reorganize primary care practices to improve the outcomes for patients, providers, and society. Overall, AHRQ has supported approximately 180 grants related to the organization of primary care and launched specific programs in the following areas: Care Coordination (including Care Management), Patient-Centered Medical Home Transformations, Team-based Care, Behavioral Health Integration, and Multiple Chronic Conditions.

Care Coordination

AHRQ defines care coordination as the deliberate organization of patient care activities and sharing of information among all the participants concerned with a patient's care to achieve safer and more effective care that meets the patient’s needs and preferences. Care coordination is especially important given the highly fragmented nature of the current U.S. healthcare system. Barriers to care coordination include: fragmentation of clinical information technology (i.e., lack of electronic health record interoperability); scarcity of specialists and/or community resources; challenges faced by providers, practices, and health systems in providing coordinated care; and patient-specific barriers (e.g., patient resistance, lack of trust, and lack of attention to self-care).40

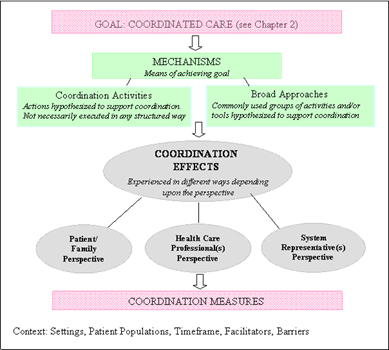

In 2007, as part of a series on "Closing the Quality Gap: A Critical Analysis of Quality Improvement Strategies" AHRQ conducted a review of reviews on care coordination. The Evidence Report concluded that, although there was a broad variety of literature related to interventions aimed at improving care coordination,41 the outcome measures used to determine the success varied and few focused on structures, processes, or intermediate outcomes of the care coordination intervention. To fill this gap, AHRQ invested in the development of the Care Coordination Measures Atlas and the Care Coordination Quality Measure for Primary Care (CCQM-PC) to measure patient, caregiver, clinicians, and health system manager experiences with care coordination using a Care Coordination Measurement Framework (Figure 5). These resources are still used today.

Figure 5. Care Coordination Measurement Framework

AHRQ has also funded several investigator-initiated grants that focused on improving care coordination at the point-of-care transitions, such as testing of technology to aid in care transitions,42 evaluation of an automated alert system to notify primary care clinicians when a patient is discharged from hospital care,43 medication adherence reporting during care transitions44, and transition coordination for pediatric asthma patients.45

Team-Based Care

Team-based care is defined by the National Academy of Medicine as "the provision of health services to individuals, families, and/or their communities by at least two health providers who work collaboratively with patients and their caregivers—to the extent preferred by each patient—to accomplish shared goals within and across settings to achieve coordinated, high-quality care."46 Care teams are groups of primary care staff members who collectively take responsibility for a set of patients through the blending of multidisciplinary skills.

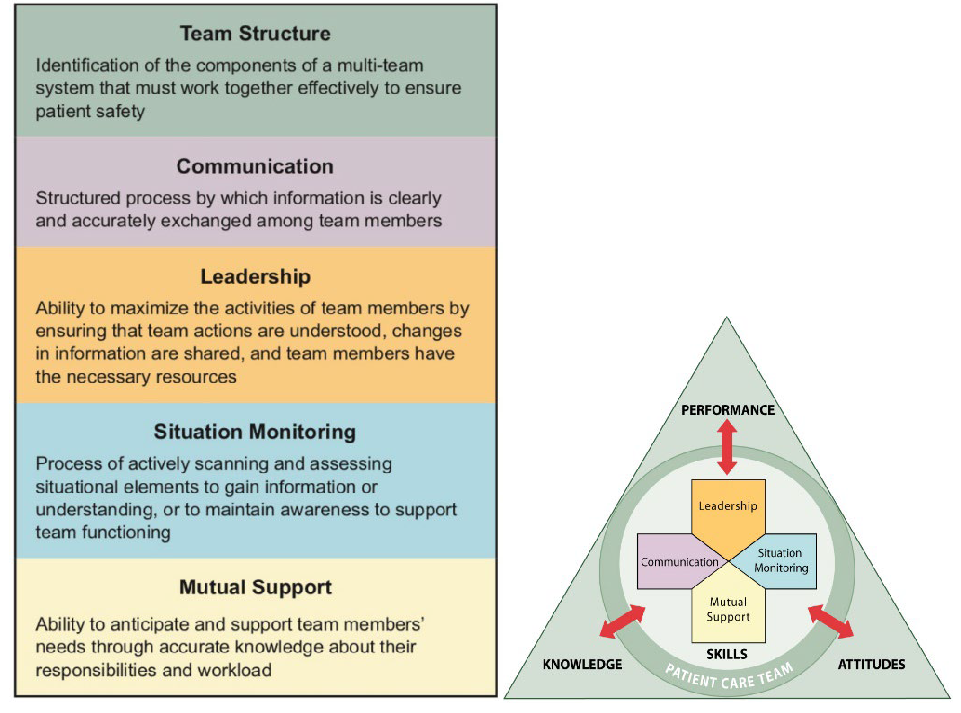

The best-known example of AHRQ's work in team-based care is TeamSTEPPS—Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety. Developed by AHRQ and the Department of Defense (DoD) in 2003, TeamSTEPPS® is a systematic approach to improving quality, safety, and efficiency of healthcare. The approach was developed based on more than 20 years of research supporting the use of teamwork in healthcare47 and the Key Principles shown in Figure 5. Other specific TeamSTEPPS projects and impact are described in the section on Safety.

Figure 6. TeamSTEPPS Key Principles

In 2006, AHRQ released TeamSTEPPS training programs and materials for use in hospitals and health systems, leading to the training of more than 6000 master trainers and nearly 40,000 trainees in three program phases by 2014: needs assessment; planning, training, and implementation; and sustainment. Subsequently, AHRQ used evolving evidence to guide the development of TeamSTEPPS for Office-Based Care (2016) curricula and programming to guide primary care office-based teams.48 TeamSTEPPS for Office-Based Care is specifically based on the following skills: communication, leadership, situation monitoring, and mutual support. The Office-Based Care approach includes external practice support in the form of TeamSTEPPS Master Trainers and implementation and evaluation resources for delivery in classroom, virtual, and hybrid formats. TeamSTEPPS Office-Based Care is approved for continuing education credit with several organizations, including the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME), American Nurses Credentialing Center (ACCME), and Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) to facilitate uptake of training by clinicians.

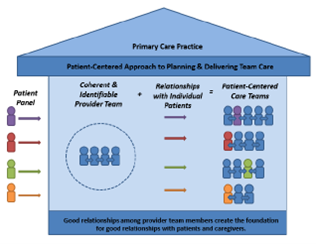

AHRQ has also further developed the conceptual framework of team-based care. In an AHRQ white paper, Creating Patient-Centered Team-Based Primary Care49 authors note that "well-implemented team-based care has the potential to improve the comprehensiveness, coordination, efficiency, effectiveness, and value of care, as well as the satisfaction of patients and providers" and that the transition to team-based care often requires "profound changes in the culture and organization of care." AHRQ's Team-Based Care white paper presented a conceptual blueprint for the provision of team-based care (Figure 7). This framework emphasizes the centrality of patient-centered care and positive relationships among providers to successful team-based care.

Figure 7. Conceptual Blueprint for the Provision of Patient-Centered Team-Based Care

The Six Building Blocks program, funded by AHRQ through a series of three R18 grants, is another example of an effective application of team-based care. Motivated to reduce the volume of opioid overdoses and deaths in the Northwest United States, and to lessen the burden of opioid prescribing on primary care clinicians, the WWAMI region's Practice Based Research Network (PI: M. Parchman) designed a team-based approach to opioid management.50 The Six Building Blocks are strategies common to successful primary care-based opioid management programs (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Overview of the Six Building Blocks

Implementation of Six Building Blocks in rural primary care practices resulted in significant decreases in opioid prescriptions.51 Clinician and staff perceptions of work-life balance also improved with the Six Building Blocks program.52 The following observations were reported: increased confidence and comfort in care provided to patients with long-term opioid therapy, increased collaboration among clinicians and staff, improved ability to respond to external administrative requests, improved relationships with patients using long-term opioid therapy, and an overall decrease in stress. Six Building Blocks programs have won awards for healthcare quality, and recently, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) incorporated Six Building Blocks into the implementation strategy for their opioid prescribing guidelines.53

With the support of AHRQ, the CDC, and the Institute of Translational Health Sciences, the original research team maintains a Six Building Blocks website, which includes a practice self-assessment, Six Building Blocks Implementation Guide, and additional resources for patients, clinics, and practice facilitators. COVID-19-specific resources have recently been added to the site. Additionally, along with the University of Washington, Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, and Abt Associates, AHRQ designed Six Building Blocks: A Team-Based Approach to Improving Opioid Management in Primary Care, a self-service how-to-guide for practices, released in early 2021.54 The Six Building Blocks approach is also being used to guide an AHRQ-funded contract to identify and test strategies to improve the management of opioids in older adults.

Other AHRQ projects to advance team-based primary care include Redesigning Primary Healthcare Teams for Population Health and Quality Improvement and A Review of Instruments to Measure Interprofessional Team-Based Primary Care55 as well as a number of grants to assess team performance in response to behavioral and social determinants of health, evaluate the impact of primary care team configuration and stability on quality of care,56 and other aspects of understanding team-based care.

Care Management

AHRQ has been involved in supporting the development, evaluation, and implementation of care management (a team-based, patient-centered approach to assist patients and their support systems in managing medical conditions more effectively). Prevention/Care Management was a portfolio area for AHRQ for many years. Within this portfolio, funding was provided for a number of investigator-initiated studies that examined the implementation and effectiveness of care management. Key among those was work by Michael Magill and colleagues at the University of Utah developing the Care by Design™ approach to facilitating chronic disease management.57,58 This approach supported the creative use of medical assistants to provide assistance to the practice team and was taken up widely by many other health systems. Another AHRQ grantee, David Dorr, developed the Care Management Plus system of personnel and technology to support chronic care management that has also become widely adopted.59-62 Additionally, Jodi Summers Holtrop investigated integration of care managers into practice compared to off-site care managers provided by health plans or health systems.63-68 The on-site model was found to be much more effective and widely adopted by health systems in the U.S. A complete summary of AHRQ's care management work is cataloged in a publication by Andrada Tomeia-Cotisel.69 In summary, AHRQ's investment in research on care management helped to make this type of care more feasible in primary care by facilitating payment for it and creating the structures to help implement it in practice.

From this work, several practical tools and resources were developed. This includes a Care Management Information Brief and a Care Management in Primary Care Implementation website. AHRQ staff facilitated development of guidelines on the role of the care manager70 and completed a summary report on the role of care management in supporting chronic disease care. AHRQ also contributed to new payment and billing codes. Care management is recognized as part of the Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH) and includes billing under Comprehensive Primary Care (CPC) Plus. Select to view materials related to Care Management Plus data visualization tools and curriculum.

Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH)

One of the pivotal developments in primary care has been the Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH). Based on the medical home concept originated by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) in the 1960s, the PCMH model of care evolved as a result of related work by numerous organizations (e.g., World Health Organization, 1978 and IOM Committee on the Future of Primary Care, 1996) and research teams.3,71,72 In 2007, the AAP, American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), American College of Physicians (ACP), and American Osteopathic Association (AOA) endorsed the Joint Principles of the Patient-Centered Medical Home. The Principles defined the PCMH as "a health care setting that facilitates partnerships between individual patients and their personal physicians, and when appropriate, the patient’s family." AHRQ elaborated on this concept and described PCMH "not simply as a place, but as a model of the organization of primary care." The five key attributes of a PCMH were defined as: (1) comprehensive care, (2) patient-centered care, (3) coordinated care, (4) accessible services, and (5) a focus on quality and safety. A number of states and organizations, including AHRQ, funded pilot work and demonstration projects focused on PCMH implementation and transformation.

AHRQ's contribution to the development of the PCMH has centered on building research methodology and infrastructure around its transformation, and between 2008 and 2019, 27% of all primary care grants explored how to fundamentally change how care is delivered, including testing or implementing PCMH models. In 2009, AHRQ and the Commonwealth Fund supported a meeting of PCMH stakeholders entitled, "Patient-Centered Medical Home: Setting a Policy-Relevant Research Agenda" convened by the Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM), Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM), and the Academic Pediatrics Association (APA). The meeting proposed measures of PCMH impact, the identification of potential measurement challenges, and recommendations for future research73 In 2010, AHRQ put these recommendations into action and awarded 14 Transforming Primary Care grants (totaling $12 million) aimed at improving understanding of transforming primary care through a retrospective analysis of systems and practices that had successfully implemented the PCMH model.74 Grantees represented a diversity of health systems, foundations, and insurers from throughout the United States.

The Transforming Primary Care grants resulted in more than 50 scientific publications. Findings were summarized and synthesized in AHRQ Transforming Primary Care Grant Initiative: A Synthesis Report, which reported collective research outcomes for access, utilization, cost, quality of care, health outcomes, patient satisfaction/experience, and provider/staff satisfaction.

In addition, McNellis et al.74 outlined key lessons learned about PCMH transformation:

- A strong foundation is needed for successful redesign.

- The process of transformation can be a long and difficult journey.

- Approaches to transformation vary.

- Visionary leadership and a supportive culture ease the way for change.

- Contextual factors are inextricably linked to outcome.

These lessons have informed AHRQ's subsequent work related to the PCMH, including methodology to evaluate the success of PCMH models, instruments and measures sets, and multiple reports and white papers. AHRQ also developed an online PCMH Resource Center as a clearinghouse of tools, data, and resources to practices, practice facilitators, researchers, and policy makers.

A separate, but related, AHRQ PCMH grant initiative, Infrastructure for Maintaining Primary Care Transformation (IMPaCT): Support for Models of Multisector, State-Level Excellence, was launched in 2011. The purpose of this initiative was to learn more about the infrastructure and support needed for successful primary care transformation. The four IMPaCT grantees represented state-level initiatives that had used a primary care extension (PCE) model approach to successfully transform practice infrastructure and improve quality of care. Modeled after the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Cooperative Extension Program, the PCE Program was authorized by U.S. Congress in Section 5405 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act in 2010. Unfortunately, the program was not funded by Congress.75 AHRQ's $4 million investment in the IMPaCT pilot grants reflected a commitment to moving primary care extension implementation and research forward.

IMPaCT grantees were based in New Mexico, North Carolina, Oklahoma, and Pennsylvania. Each state-level program committed to build upon PCMH initiatives through the primary care extension program implementation and quality improvement initiatives in small primary care practices (more than 120 practices were represented among the four grantees). In addition, each grantee was responsible for collaborating with three to four partner states (17 additional states were represented in all) to develop, expand, and improve the primary care extension programming, and to evaluate their programs using quantitative and qualitative methodology.76 Practice facilitators or health extension agents serving in a practice facilitation role were central to each of the primary care extension programs.

The work of all four IMPaCT grantees is summarized in the form of success stories on the AHRQ website, in the AHRQ Infrastructure for Maintaining Primary Care Transformation (IMPaCT) Grants: A Synthesis Report, and by Kaufman et al.76 Collectively, the IMPaCT investment facilitated an innovative approach to primary care transformation and quality improvement through practice facilitation, partnerships with other public agencies, policy-makers, key stakeholders, and interstate collaborations.

As an example of grantee work, the New Mexico research team incorporated collaboration among 34 primary care practices (mostly small, rural practices), Health Extension Regional Offices (HEROs), universities, Area Health Education Centers (AHECs), the state department of health, and other community-based organizations to address social determinants of health among the state's residents and share resources in promoting quality improvement in primary care. Art Kaufman, the primary investigator for the New Mexico grant describes their IMPaCT work as addressing the "social and economic forces that undermine physicians' ability to help patients." Practice facilitation conducted by health extension coordinators (also known as HEROs) recruited from within the communities they were serving was considered paramount to the program's success. Among other services, HEROs advised practices as they transitioned to a PCMH model, provided technical and operational expertise related to EHR interoperability and data extraction, and connected practice clinicians and staff with professional and community resources. They even played a role in securing housing for families of hospitalized patients. The HERO program consulted with primary care collaboratives and practices in Kansas, Kentucky, and Oregon to share their learning and provide support for implementation of the primary care extension model. Outcomes of AHRQ's investment in HERO include an IMPaCT online toolkit, training program for community health workers focused on low-income populations, and the creation of new health-sector jobs.

Similar to the Transforming Primary Care initiative, lessons learned from IMPaCT projects were compiled:

- Extension efforts require coordination.

- IMPaCT grants built and sustained the complex partnerships that were necessary for the multiparty efforts required for successful extension programs.

- Local tailoring is essential.

- The focus of spread activities was on creating capacity for improvement through state partnerships rather than replication of the specific model used by the model state.

- Structured peer-to-peer learning improved capacity at all levels of primary care transformation support.

- Gaining practice buy-in is critical.

- External influences also relate to practice buy-in.

- Practice facilitators provide essential support to practices.

Outcomes of the IMPaCT investment include the development of multiple primary care extension tools and resources, primary care transformation curricula and training programs, numerous scientific publications,77 and on-going implementation of IMPaCT initiatives and infrastructure. The impact of this initiative is also reflected in laying the foundation for future investments in primary care transformation, with the Estimating Costs of Supporting Primary Care Transformation grant initiative serving as one example.

Estimating Costs of Supporting Primary Care Transformation (2013) was a $1.5 million investment aimed at providing stakeholders with information about the costs associated with implementing and sustaining transformative primary care practice redesign. Grants (R03) were awarded to 15 research teams who worked with more than 700 primary care practices varying in size, setting, and primary care population. A variety of methods were used to estimate different types and categories of costs. Fleming et al.,78 for example, used activity-based coding methodology to estimate costs of established primary care practices' initial PCMH transformation and accreditation, in addition to the direct and opportunity costs associated with PCMH recognition renewal. A gross-costing approach was used by Shao et al.79 (PI: L. Shi) to estimate costs incurred by New Orleans safety net practices that completed PCMH transformation compared with those that did not. Summaries of the work of all of the Estimating Costs of Supporting Primary Care Transformation grantees are available on the AHRQ website. Ultimately, evidence from the 15 grantees informed the development of Estimating the Costs of Primary Care Transformation: A Practical Guide and Synthesis Report.80

Taken together, AHRQ's investment in primary care transformation through the Transforming Primary Care, IMPaCT, and Estimating Costs of Supporting Primary Care Transformation initiatives contributed to the widespread evolution of the PCMH and advancement of related research. It provided evidence to support the Transforming Clinical Practice Initiative (TCPI) Awards ($685 million) administered by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and Comprehensive Primary Care Plus (CPC+), an advanced PCMH model administered by Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI). AHRQ also established the Federal PCMH Collaborative as a forum for federal government agencies to collaborate and coordinate research, dissemination, and implementation related to the PCMH. Through this collaborative, the Veteran's Health Association (VHA) PCMH model, known as the patient-aligned care team (PACT), was developed.

The National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) and others continue to accredit and recognize PCMH practices today, and the PCMH model has become integral to primary care. However, as Robert McNellis, former Senior Advisor for Primary Care at AHRQ stated, "maybe what we have learned more than anything else is the name [PCMH] matters less than the substantive changes behind it…keeping in mind it is just one model of moving primary care from the old model to new ones that deliver better outcomes, better care, and better value" (personal communication).

Integrating Behavioral Health with Primary Care

Behavioral health is an umbrella term that encompasses mental healthcare and substance abuse treatment, in addition to health-related behaviors and the effect of stress on physical symptoms. In recognition of both medical and behavioral health factors' contributions to overall health and well-being, the integration of behavioral health in primary care emerged as an effort to reorganize primary care. If done successfully, integration of behavioral health and primary care can improve coordination, communication, and whole-person care. Behavioral health integration into primary care is an important focus for AHRQ, and 18% of all primary care research grants between 2008–2019 had a mental/behavioral health focus.

In 2008, with the support of the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), and the Office of Women's Health and the Office of Minority Health, the AHRQ Evidence-based Practice Center (EPC) program produced a systematic review entitled, Integration of Mental Health/Substance Abuse and Primary Care in 2008.81 This report identified that behavioral health issues are commonly encountered in primary care, occur at a higher rate among patients with chronic disease, and that efforts to integrate behavioral healthcare and primary care had been successful (especially for depression). The report also established that "improvements in the coordination between mental health and primary care can contribute to both better quality and lower costs."

The Integration of Mental Health/Substance Abuse and Primary Care report also identified several research gaps, including care integration for conditions other than depression and for patients with serious and persistent mental illness, and the need to better understand how information technology and financial models could support the behavioral healthcare integration in primary care.81 AHRQ addressed these gaps in two ways: (1) by investing in a second systematic review to highlight research needs for integration82 and (2) by funding the first national conference of the newly formed Collaborative Care Research Network (CCRN), a subnetwork of the American Academy of Family Physicians National Research Network (AAFP NRN). Outcomes of the CCRN Conference included a research agenda, metrics framework, and importantly, a lexicon for behavioral healthcare integration.83 Comprised of concepts and definitions related to the integration of behavioral health in primary care practice settings, the Lexicon aimed to create a common language for researchers, clinicians, and policy-makers.84

The Lexicon was developed further in an AHRQ-sponsored collaborative conference with the National Integration Advisory Council (NIAC).85 The NIAC ultimately established the Academy for Integrating Behavioral Health and Primary Care, which is an online community to foster dialogue among individuals and practices working to integrate behavioral health and primary care that remains active today. The Academy, which attracted more than 70,000 users in FY2019, hosts numerous resources and tools to help primary care providers, including interactive playbooks on how to integrate behavioral health and medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder into primary care or other ambulatory care settings, tools and resources, and expert insights.

Since the establishment of the Academy, AHRQ has also funded more than 80 grant projects related to behavioral health, totaling nearly $40 million, including three multi-grant programs to address the need for better management of substance use disorders. In 2016, AHRQ launched the "Increasing Access to Medication-Assisted Treatment of Opioid Abuse in Rural Primary Care Practices" to support rural primary care practices in delivering medication-assisted treatment (MAT). Grantees in Oklahoma, Colorado, Pennsylvania, and North Carolina (a fifth state, New Mexico, was added in the following year) used the Project ECHO Hub and Spoke model of care and practice facilitation to enhance MAT for opioid use disorder in rural communities. Through telementoring learning communities, state health departments, academic health centers, researchers, local community organizations, and healthcare clinicians collaborated to bring evidence-based MAT to more than 20,000 patients.

In 2019, AHRQ launched a grant initiative to reduce Unhealthy Alcohol Use, which has disseminated and implemented into primary care practices evidence-based approaches to improve the use of screening for unhealthy alcohol use, brief intervention for those at risk, and medication therapy for alcohol use disorder. Together, the 6 grantees worked with close to 300 primary care practices across the country. The implementation strategies incorporated AHRQ's established EvidenceNOW model for practice support. Early findings show significant improvements in screening rates for several projects.

In 2020 AHRQ awarded three grants in response to the number of hospitalizations and emergency department visits related to opioids among older adults. The Management of Opioids and Opioid Use Disorder in Older Adults grants will develop, implement, evaluate, and disseminate strategies to improve the management of opioid use, misuse, and opioid use disorder (OUD) in older adults in primary care settings. These grants are part of a broader AHRQ initiative to improve management of opioids among older adults that includes a technical brief and an ACTION learning collaborative.

Multiple Chronic Conditions (MCC)

Improving outcomes for patients with multiple chronic conditions (two or more chronic conditions) or MCC is a major challenge for the healthcare system, particularly in primary care. Approximately half of people ages 45–64 and 80% of those older than 65 years of age experienced MCC, and the proportion of Americans impacted was on the rise.86 MCC are associated with decreased functional status, poor health outcomes, and mortality.86 Unnecessary hospitalizations, adverse drug events, and conflicting medical advice add to the burden of MCC to patients and their families.87 In addition, MCC are associated with high healthcare costs to both patients themselves, and the overall healthcare system. More than two-thirds of healthcare expenditures were dedicated to patients with MCC.88 Improved care coordination for patients with MCC has the potential to improve all these outcomes.39

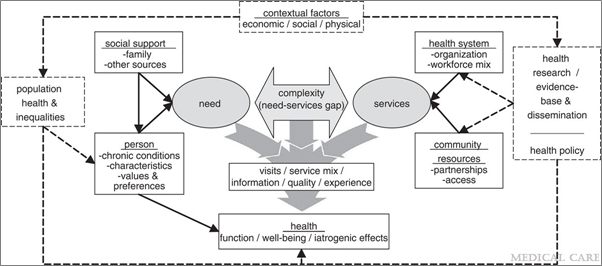

From 2008 to 2019, 9% of all primary care research grants focused on MCCs. In 2010, responding to the fact that nearly 100 million Americans were living MCC, and that primary care clinicians needed better tools to treat MCC, AHRQ funded the AHRQ MCC Research Network. The goal of the Network was to advance evidence-based care for individuals living with MCC in alignment with the HHS MCC Strategic Framework.89 Specifically, the MCC Network aimed to uncover "how health systems and healthcare professionals can better partner with patients living with MCC to create patient-centered management plans."90 This network included a MCC Learning Network and Technical Assistance Center to provide support and facilitate communication among MCC researchers. One network outcome involved the development of a MCC Conceptual Model (Figure 9)91 that positioned the relationship between an individual's needs and the capacity of healthcare services to support these needs central to the model.

Figure 9. A Conceptual Model of the Role of Complexity in the Care of Patients with Multiple Chronic Conditions91

Collectively, the network "advanced the field of MCC research, provided guidance to clinicians and patients, and advised policymakers about improved methods for measuring and promoting quality care for MCC patients."89 In addition, a Medical Care Journal supplemental issue and more than 85 scientific publications resulted from network initiatives. Research findings were also presented at numerous professional conferences, meetings, and webinars. The MCC Chartbook,92 developed based on MEPS data to provide stakeholders with nationally representative data about patients with MCC, was also an outcome of AHRQ's MCC work.

Building on this work, in 2014, AHRQ funded 14 additional grant projects: seven large (R01) grants and seven R21grants focused on research methodology and the use of large data sets to advance care for patients with MCC. One of the grantees, a Duke University research team (PI: M. Maciejewski), explored medication prescribing in Medicare patients with cardiometabolic conditions across 10 states. Results showed that the nearly 400,000 patients studied averaged five chronic conditions and took 10–12 medications, on average.93 Importantly, the results also showed that patients who saw more healthcare providers took more medications and were more likely to be prescribed duplicate medications than patients with the same conditions who saw fewer providers. This work resulted in recommendations for improved care coordination for patients with MCC and led to the 2020 summit on transforming care for MCC.

AHRQ applies the Care and Learn Model, developed by AHRQ researchers to map the work of the Agency and its research portfolio, to identify areas of unmet need and prioritize research questions with the most value for advancing the care of people with MCC. The Care and Learn Model starts by placing the patient at the center of care. It encourages learning about how best to care for patients by closely evaluating how well patients are doing and identifying which of their needs are not being met.

The model aligns the two primary functions of the health system: providing care that meets the needs of diverse individuals and populations and continually learning by implementing evidence and using data to increase our understanding of what works. The Care and Learn Model brings together essential caring functions with data-driven evidence generation, synthesis, and implementation.94

Quality

Quality improvement (which refers to a continuous and ongoing effort to achieve measurable improvements in the efficiency, effectiveness, performance, accountability, outcomes, and other indicators of quality in services or processes which achieve equity and improve the health of the community) has been a part of the Agency's mission since the establishment of AHCPR in 1989. The Agency has made significant investments in research to identify effective methods and strategies for quality improvement in primary care, although between 2008 and 2019, only 9% of all funded primary care grants explicitly used quality improvement processes to achieve the intended outcome.

Practice Facilitation

Practice Facilitation (PF) is one of AHRQ's best known examples of how to put evidence into action. One AHRQ leader stated, "At AHRQ, we believe that the secret ingredient for helping practices make substantive and meaningful changes necessary to improve care is practice facilitation." Practice facilitators utilize a variety of strategies and methods focused on organizational development, project management, quality improvement, and practice improvement.

The history of PF dates to the Oxford Heart Attack and Stroke Project (England) in the mid-1980s,95 but has since gained popularity in the U.S. and other countries.96 Practice Facilitation involves the provision of ongoing external support (i.e., practice facilitators) to primary care practices with a goal of improving patient outcomes and developing practice capacity for sustained quality improvement.96 Recognizing that "most practices lack time, energy, and resources to make changes on their own, and most lack means of learning about the policies pushing them to change or examples from which they can learn," practice facilitators "help physicians and improvement teams develop the skills they need to adapt clinical evidence to the specific circumstance of their practice environment."77

AHRQ’s 2010 Consensus Meeting on Practice Facilitation for Primary Care Improvement, which convened a panel of PF experts to advance knowledge of PF, identify best practices, and explore needs for future work, served as a launching pad for multiple investments in PF. AHRQ initially developed a portfolio of PF resources and tools as part of the PCMH work, including a dedicated web page within the PCMH Resource Center, webinars, a how-to guide, model curriculum, handbook, and exemplary case studies, in addition to products focused on PF for health information technology integration, quality improvement, and patient-centered care. AHRQ's 14 Practice Facilitation training modules are available for learners and trainers. Building on this resource, AHRQ worked with the North American Primary Care Research Group (NAPCRG) to hold the first International Conference on Practice Facilitation in 2017,97 which continues annually, opening the door for relationships among practice facilitators from multiple countries.

As of 2020, AHRQ's largest investment in primary care research ($112 million) was EvidenceNOW: Advancing Heart Health, which was designed to evaluate the effectiveness of PF and other external supports (ex: academic detailing and learning collaboratives) in primary care quality improvement and in building the capacity for implementing patient-centered outcomes research findings. The initiative aligned with the Department of Health and Human Services' Million Hearts national initiative to prevent 1 million heart attacks and strokes within 5 years.98 Seven implementation grants were awarded to regional cooperatives throughout the U.S. Grantees were tasked with designing multi-component external quality improvement interventions (ex: practice facilitation; data, feedback and benchmarking; health information technology support; local learning collaboratives; and/or academic detailing) to improve the ABCS of heart health (i.e., appropriate Aspirin use, Blood pressure control, Cholesterol management, and Smoking cessation support) in small or medium-sized primary care practices.

Mostly small and medium-sized practices of <10 clinicians were recruited since they represented nearly 90% of office visits in the United States99 and have been shown to have fewer resources dedicated to quality improvement.100 In addition to the seven implementation grants, AHRQ also provided grant funding to ESCALATES, an independent national evaluation of EvidenceNOW.17

Overall, EvidenceNOW: Advancing Heart Health practice facilitators worked with 1500 primary care practices, 5000 primary care professionals, and more than 8 million patients.101 Final results are published on AHRQ's website. EvidenceNOW: Advancing Heart Health demonstrated promising results with practices participating in the initiative. For example:

- Practices across the Cooperatives dramatically improved the number of QI strategies used to improve care.

- In almost every Cooperative, practices with lower baseline QI capacity made larger improvements than practices that started with higher capacity.

- More hours of practice facilitation, and more months with at least one practice facilitation visit, were associated with larger improvements in QI capacity. Frequent and consistent practice facilitation works best.

Findings showed that EvidenceNOW practices also improved heart health services and outcomes at significantly greater rates after receiving external support than before receiving support, including a:

- 7.3% increase in smoking screening and cessation counseling.

- 3.4% improvement in prescribing aspirin for eligible patients.

- 4.4% increase in cholesterol management.

- 1.6% increase in blood pressure control—an important finding, given decreasing national rates of blood pressure control.

The late Dr. David Meyers, AHRQ’s Deputy Director and Chief Physician at the time, shared that "what we learned about the practices and the implementation process is perhaps even more valuable than the ABC outcomes measures themselves in terms of creating a foundation for quality improvement in primary care". For example, EvidenceNOW projects have both elucidated the barriers to obtaining consistent and reliable EHR data for quality improvement efforts102-104 and described the approaches that practice facilitators have used to problem-solving related to multiple EHR challenges encountered by practices.105

The model of Practice Facilitation that EvidenceNOW tested has extended through numerous scientific publications, a collection of EvidenceNOW implementation tools and resources, and has become the basis of numerous subsequent dissemination projects, both at AHRQ and beyond. Robert McNellis, former Senior Advisor for Primary Care at AHRQ, described EvidenceNOW as having "changed the culture of primary care. People refer to it at conferences and in the regular language of primary care."

Improving Equity in Primary Care

Improving healthcare quality through the provision of equitable, accessible care for all Americans is an important part of AHRQ's mission. The Agency has specifically invested in research to reduce disparities in primary care, in addition to the generation of data for this research. Published since 2003, the National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report is a key example. This report includes information related to care access, cost of care, care coordination, effectiveness of treatment, patient safety, healthy living and person-centered care, as well as disparities associated with race and ethnicity and other social determinants of health. National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report data previously revealed disparities in occurrence of and treatment for hypertension, with non-Hispanic Blacks and Native Hawaiians demonstrating poorer blood pressure control. This information has informed programs and future research to reduce disparities in the prevention, identification, and treatment of hypertension.

In addition to the National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report, an internal portfolio analysis of AHRQ primary care research grants between 2008 and 2019 (see Appendix A) found that 20% focused on racial/ethnic minorities or LGTBQ, 15% on low-income populations, and 3% on those with disabilities and special health needs. Overall, 37% of grants specifically addressed the needs of AHRQ priority populations.

The Effective Healthcare Program

To deliver high-quality care, providers and health systems need to know which interventions and programs actually work. Although this sounds straightforward, finding, interpreting, and synthesizing all the available studies into a reliable and actionable conclusion is anything but simple. To meet this challenge, AHRQ created the Evidence-based Practice Center program in 1997 with the goal of helping consumers, healthcare professionals, and policymakers make informed and evidence-based healthcare decisions. In 2005, the Effective Healthcare Program was built around the EPC program to support methods development and dissemination. Although the EPC program is not restricted to primary care, primary care topics (such as gastroesophageal reflux disease, diabetes, and hypertension) make up the largest set of review topics, and the EPC program partners with the major primary care guideline groups, including the AAFP, AAP, ACOG, and ACP to support the development of guidelines for primary care.

"Throughout my career I've relied on AHRQ for their compendium of research reviews. I actually was just looking at an AHRQ report today about mobile health apps for improving diabetes control."

- RAND interviewee

While the EPC program focuses on providing relevant and timely answers to meet the needs of decision makers, the EPC program has also had an impact on primary care research, by setting standards and defining research priorities in primary care topics. The EPC program pioneered standards for conflict of interest and stakeholder engagement in systematic reviews106 and developed a systematic approach to identifying evidence gaps and research needs as an integral product of the review process. In addition, the EPC program provides the evidence reviews for the NIH’s Pathway to Prevention program, which identifies methodological and scientific weaknesses in specific disease areas (many of which fall under primary care), suggests research needs, and seeks to move the field forward through an unbiased, evidence-based assessment of a complex public health issue.

Person-Centered Care

Primary care cannot be patient-centered without understanding how to improve both personal and organizational health literacy. AHRQ's many research investments in health literacy have produced findings and tools that contribute to the delivery of high-quality healthcare. These include:

- Seminal evidence reviews of the association of literacy and health outcomes and health literacy interventions.

- Intellectual contributions that have produced conceptual models and frameworks, such as the Health Literate Care Model107 and the Ten Attributes of a Health Literate Organization, as well as other articles and book chapters related to health literacy.

- Testing of tools in and for primary care practices, such as the AHRQ Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit and the Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT).

- The AHRQ Informed Consent and Authorization Toolkit for Minimal Risk Research, which helps the primary care research community ensure inclusion of populations with limited health literacy in studies.

- Research measures of health literacy that enable study of health literacy disparities and examine interventions' effects on populations with limited health literacy.

- Survey measures and data on health literate practices by providers, including CAHPS supplemental items on health literacy and microdata from the AHRQ's Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS).

Self-management support is an important part of both patient-centered care and care coordination in primary care settings. Managing chronic illness and changing behavior are challenging and take time for everyone involved—providers, patients, and caregivers. Yet, it is often patients themselves who are called on to manage the broad range of factors that contribute to their health. Using self-management support in primary care can have a positive effect on the care and health outcomes of people with chronic conditions, as well as provider and patient satisfaction. AHRQ has developed a variety of resources to help primary clinicians and teams learn about and implement self-management support, including a library of resources and videos to help clinicians learn and implement this concept, and The Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT) and User’s Guide. The PEMAT is a systematic method to evaluate and compare the understandability and actionability of patient education materials. It is designed as a guide to help determine whether patients will be able to understand and act on information. Although the PEMAT is not restricted to primary care research, patient education is central to primary care.

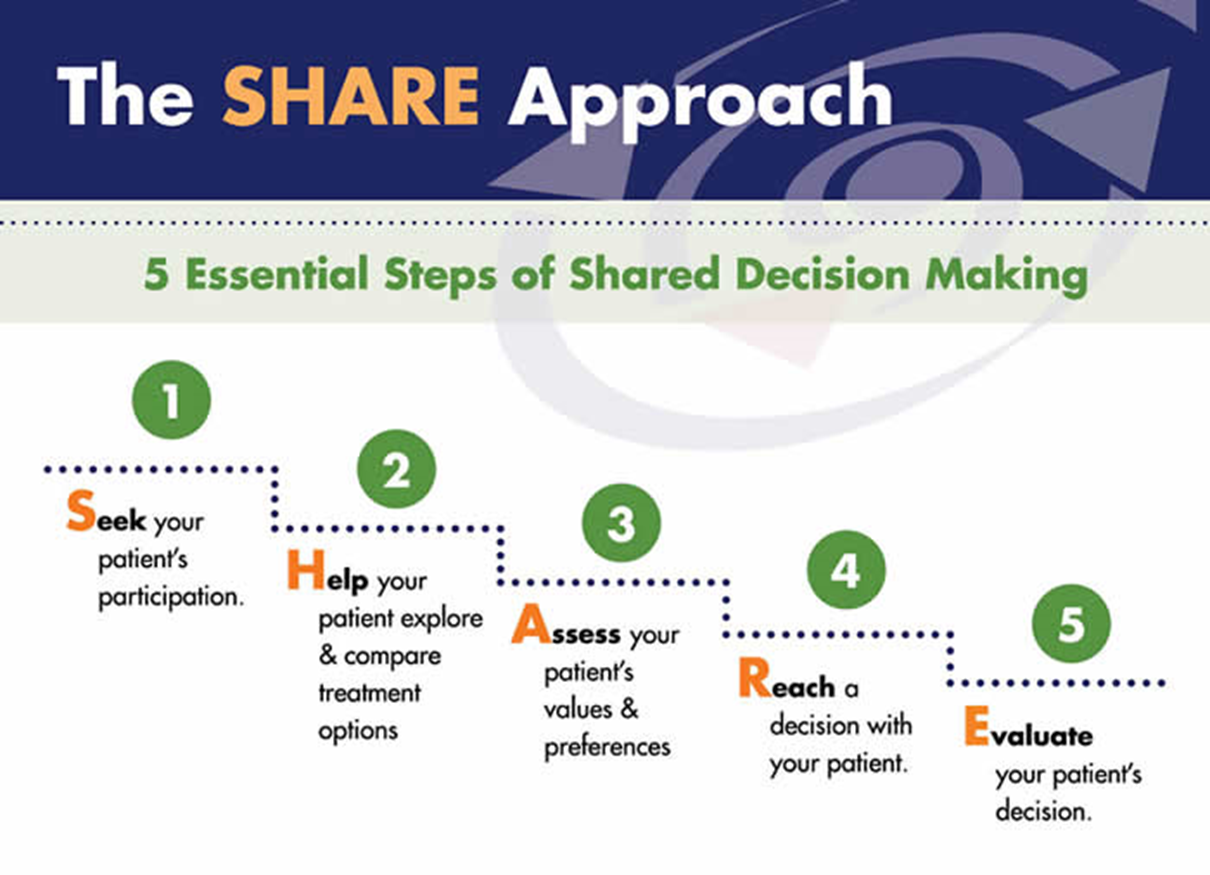

Shared Decision Making

AHRQ’s SHARE Approach (Figure 10) is a five-step process for shared decision making that includes exploring and comparing the benefits, harms, and risks of each option through meaningful dialogue about what matters most to the patient. A Fact Sheet about the program is available, and the SHARE Approach Workshop curriculum was developed to support the training of healthcare professionals on how to engage patients in their healthcare decision making. In addition, a collection of reference guides, posters, and other resources, were designed to support implementation of AHRQ's SHARE Approach.108

Figure 10. AHRQ's SHARE Approach

Safety

AHRQ is known for prodigious work in healthcare safety. The focus on safety grew after the 1999 IOM seminal report, To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System, as part of their Quality of Health Care in America series. This report described the current state of medical errors and safety risks in the healthcare setting, positing that "the problem is not bad people in health care—it is that good people are working in bad systems that need to be made safer."109 A call for research to design a safer health care system was put in motion. Under the direction of Helen Burstin, CP3 Director, AHRQ responded by funding a conference, in conjunction with CMS and the Partnership for Patient Safety, to develop a research agenda related to ambulatory patient safety in 2000. This enhanced focus on safety kicked off a consistent commitment to research aimed at improving patient safety across healthcare, including in the primary care setting, and between 2008 and 2019, 31% of primary care grants included improving patient safety as an intended outcome or justification.

"So if I had to say what's been the biggest impact of AHRQ's research, I'd say the most publicized and well-documented impact is on safety. I think that they can really take credit for a lot of that work. Yes, CMS and others contributed, but they were the knowledge engine that helped to make that happen. And AHRQ really is that knowledge engine, sort of the intel inside. It needs to create the evidence and the tools and the ability for the system to improve."

- RAND interviewee

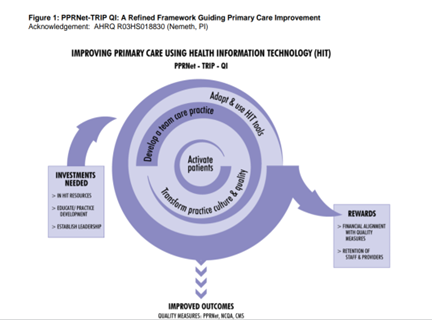

Medication Safety

Between 2008 and 2019, 13% of awarded grants explored interventions intended to ensure that patients are on the correct medications (i.e., reconciliation) or that patients adhere to their medication regimens. Forty Ambulatory Safety and Quality Program (ASQ) projects involved medication management and safety. One example was the Medication Safety—Translating Research into Practice (MS-TRIP) project conducted by the Practice Partner Research Network (PPRNet, 160 primary care practices in 41 states), which provided several forms of support to practices to aid in the use of their EHR's medication safety clinical support features. Over a two-year period, improvements in medication safety, including avoidance of potentially inappropriate therapy and monitoring of potential adverse events, improved significantly. The intervention and medication prescribing indicators developed in the study have been published110,111 and continue to inform quality and safety within this practice network and others.

"And the other thing that I would say that is impactful, AHRQ has been successful in drawing attention to patient safety in primary care. Because when you look at the literature, most patient safety studies are done in hospitals. And primary care is also sensitive to, you know, patient safety threat. And I think those two areas are that makes AHRQ unique and impactful."

-RAND interviewee

Following completion of the MS-TRIP study, AHRQ contracted with PPRNet (PI: L. Nemith) as part of the Practice-Based Research Network (PBRN) funding mechanism to pilot test a digital health intervention aimed at improving delivery of preventive services in eight primary care practices.112 Through the use of electronic standing orders and innovative service delivery by nurses and medical assistants, Screening, Immunizations, and Diabetes Care Management (SO-TRIP) was associated with significant improvements in the delivery of preventive screenings, immunizations, and diabetes care measures. For example, administration of the influenza vaccine in older adults increased from 8% pre-intervention to 37% post-intervention. Similarly, hemoglobin A1c screening increased from 6% to 54% with the intervention. This process, along with qualitative data collected from the research team about adoptability and sustainability of electronic standing orders, EHR technical issues, and reimbursement policy challenges were used to improve quality of care throughout the PPRNet learning community and to inform further research.112-114

Comprehensive Unit-Based Safety Program (CUSP)

The Comprehensive Unit-Based Safety Program (CUSP) is one of AHRQ's most recognized safety initiatives. CUSP was designed to reduce the occurrence of healthcare-acquired infection (HAI) and promote patient safety. Based on seminal work completed by Peter Pronovost and team at Johns Hopkins University in 2001, CUSP focuses on how clinical team members work together through safety education, process improvement, teamwork, and learning from results to improve patient safety.115,116 The effectiveness of CUSP was evaluated and validated at numerous hospitals throughout the U.S. and in 2014, was adapted for the primary care setting.117 The CUSP model has been implemented nationally and endorsed by more than 40 state hospital associations and the American Hospital Association. Dr. Pronovost has remarked that the broad impact of CUSP "started with just an initial $500,000 investment from AHRQ."

Care Transitions

Another area of healthcare that AHRQ has targeted to improve patient safety is care transitions. For example, a 2014 AHRQ grant (PI: Hewner) funded the development and pilot testing of a clinical decision support and health information exchange designed to improve care transitions for Medicaid patients with MCC. Through automated care transition alerts to primary care practices when a patient was discharged from the hospital, coordination of care for MCC patients improved and subsequent emergency department utilization and inpatient hospital stays declined. This research and others were identified by 2020 AHRQ-funded work by John Snow, Inc. that supported exploratory research into innovative approaches to care transitions aimed at reducing hospital readmissions, a primary care version of AHRQ’s Re-Engineered Discharge (RED) initiative. A conceptual framework related to primary care approaches to reduce hospital readmissions was developed.118 The conceptual framework has five principles, or fundamental concepts:

- The primary care team should serve as the key integrator of patient care.

- Several critical steps differentiating a post-discharge follow-up visit from a typical office visit require reliable primary care systems to be in place. (See the Final Report: Potentially Preventable Readmissions: A Conceptual Framework to Rethink the Role of Primary Care)

- Within the primary care practice, high-quality care transitions require defining a system of care that is team-based and encompasses the admission, the immediate post-discharge period, the first follow-up visit, and the immediate post-visit period, including additional follow-up visits.

- At the healthcare systems level, primary care must develop and implement a systematic approach to timely, appropriate, bidirectional information exchange and coordination with hospitals, post-acute care agencies, and behavioral health and social support services.

- The primary care team must systematically assess and address whole-person needs in a patient-centered fashion that leverages the clinician-patient relationship.

TeamSTEPPS®

TeamSTEPPS® Office-Based Care (described above in the team-based care section) has decreased clinical error rates, improved communication, and resulted in improved patient satisfaction.48 MetroHealth, an Ohio-based health system that includes 23 primary care centers and 1.2 million ambulatory visits annually, showed benefits of system-wide TeamSTEPPS implementation on quality and safety. They observed increased team awareness, clarified team roles and responsibilities, conflict resolution, and improved information sharing among clinicians and staff. MetroHealth and six other health systems or academic medical centers have been designated as Regional Training Centers, working to expand TeamSTEPPS training opportunities. Some TeamSTEPPS trainings have been delivered using innovative pedagogy, including virtually119 and with the incorporation of simulation.

Primary Care Workforce

Describing the Workforce

AHRQ has sponsored multiple initiatives to evaluate and assess the primary care workforce and improve the workforce experience. In 1999, for example, an AHRQ-funded team attempted to quantify the number of generalist physicians practicing in the U.S. using the Physician Masterfile of the American Medical Association (AMA).120 They reported that only 25% of U.S. physicians were generalist-only (as opposed to specialists also providing general healthcare services), which is less than previously reported. Ten years later, AHRQ commissioned the Robert Graham Center, a non-partisan primary care policy and analysis organization, to conduct a primary care workforce analysis.121 One impactful outcome of the Graham Center analysis was an estimate of future demand for primary care. This estimate, and other data, informed the 2010 Affordable Care Act's Primary Care provisions, which established incentives for medical students specializing in primary care, expansion of primary care training programs, and the National Healthcare Workforce Commission, among other provisions.

Expanding the Workforce

In addition to simply describing the primary care workforce, AHRQ has worked to identify strategies to expand it. AHRQ-funded research teams122,123 outlined recommendations for addressing the primary care workforce crisis—that is, decreasing numbers of medical school graduates entering a family medicine or internal medicine residency program and the diminishing number of primary care physicians who remain in the profession. Schwartz et al.122 stated that, "in the absence of a major overhaul of economic incentives in favor of generalist careers, we will need to work at these multiple levels to restore balance to the generalist physician workforce and align with the desires and expectations of patients for continuing healing relationships with generalist physicians." Economic incentives proposed by Song et al.123 proposed that CMS reward teaching hospitals whose graduates remain in primary care for three or more years.

Expanding the role of the nurse practitioner (NP) and physician assistant (PA) in primary care is another approach to building the primary care workforce. AHRQ funded a University of Texas Medical Branch team (R01, PI: Y. Kuo) to explore the role of the NP in the primary care of older adults. This work resulted in 22 peer-reviewed publications. Researchers specifically reported a 170% increase in the number of Medicare patients using NPs as their primary care provider from 2007 to 2013.124 No differences in complexity of patients treated by NPs and physicians were observed,124 and patients with diabetes who were treated by NPs were less likely to be hospitalized than patients treated by physicians.125 AHRQ also sponsored a Northeastern University team (R03, PI: L. Poghosyan) to develop a NP primary care organizational climate questionnaire and evaluate factors that influence NP autonomy, job satisfaction, and effectiveness in primary care.126-129 In a third AHRQ-sponsored project, Predictive Modeling the Physician Assistant Supply: 2010 to 2025, Hooker et al.130 projected growth of the PA profession and made recommendations for education and policy steps to enhance the primary care PA workforce. As part of their work with AHRQ, the Graham Center developed a "facts and stats" communication related to primary care NPs and PAs in the United States.

Re-Configuring the Workforce

Although team-based care was associated with high-quality primary care,49 in 2008, there was a paucity of information concerning the composition of successful primary care teams. Thus, AHRQ commissioned a contract team comprised of AHRQ, Abt Associates, MacColl Center for Health Care Innovation, and Bailit Health, LLC researchers to perform a mixed-methods evaluation of primary care workforce configurations. Quantitative and qualitative data from more than 70 primary care practices participating in primary care innovation programs were used to form configuration and staffing models (The Index Model, High Geriatric Model, High Social Need Model, and Rural Model), and to estimate associated costs of each configuration.131 Information learned from this project is summarized in a New Models of Primary Care Workforce and Financing Case Example series.132 The series also highlights the innovative incorporation of a variety of healthcare professionals, including community health workers, care managers, pharmacists, and scribes in the primary care setting.133 Taken together, this work is predicted to inform primary care staffing and ongoing discussions related to workforce planning.

Sustaining the Workforce

Experts in health services have recommended the recognition of a healthcare Quadruple Aim, which adds healthcare provider joy and well-being to the broadly recognized goals of improved health outcomes, enhanced patient experience, and reduced costs.134 Provider dissatisfaction and burnout—a long-term stress reaction marked by emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and lack of sense of personal accomplishment—can impact quality of care, patient satisfaction, and ultimately, health outcomes. Furthermore, as described in a 2017 blog post by then AHRQ Director, Gopal Khanna and CEPI Director, Arlene Bierman, "the emotional exhaustion of burnout can have professional and personal consequences for physicians. Burnout can damage morale and lead once-enthusiastic, dedicated doctors to quit practicing medicine completely. It can also lead to depression, alcohol abuse, and thoughts of suicide."

Clinician satisfaction and the minimization of burnout have been important foci for AHRQ since the early 2000s.135-141 Mark Linzer, a leading physician burnout researcher from the Minneapolis Medical Research Foundation, has led several AHRQ-funded studies. The initial study, Minimizing Error, Maximizing Outcome (MEMO), reported that work conditions, such as time pressure, chaotic environments, low control over work pace, and unfavorable organizational culture, were strongly associated with physicians' feelings of dissatisfaction, stress, burnout, and intent to leave the practice.142 Nearly half of participants (primary care physicians in New York, Chicago, and Wisconsin) described their practice environment as "trending toward chaotic" or "chaotic", while 61% reported that their work was stressful and 27% described symptoms of burnout. On a positive note, stress and burnout rankings were not associated with quality of patient care, medical errors, and patient satisfaction. Further work by Dr. Linzer's team focused on the impact of practice chaos,143 "the electronic elephant in the room", the EHR.144-146 AHRQ awarded an implementation grant (R18) for the Healthy Work Place study to Linzer’s team in 2009.147 In this study, interventions (12-18 months) to address communication and workflow and quality improvement projects were effective in reducing burnout and improving quality of care among New York primary care clinics.

In 2014, Linzer and his colleagues148 published "10 bold steps to prevent burnout" (Figure 11).

Figure 11. 10 Bold Steps To Prevent Burnout

Institutional Metrics

- Make clinician satisfaction and wellbeing quality indicators.

- Incorporate mindfulness and teamwork into practice.